Barking roosters and crowing dogs

« previous post | next post »

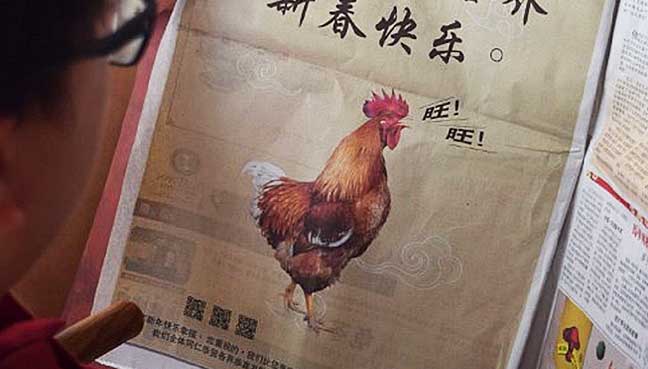

The following full-page ad was published in a Chinese daily in Malaysia:

It shows a rooster barking to welcome in the Chinese New Year (CNY).

The picture comes from this article:

"Only in Malaysia do absurdities like a CNY ‘barking’ rooster thrive", by (Free Malaysia Today [February 18, 2018]).

The article begins:

Our institutions are either gripped by a tide of Islamic conservatism, or are paralysed by supervisors who are lazy, and do not believe in proofreading.

The latest public show of incompetence occurred when a ministry decided to omit the dog from the Chinese New Year (CNY) advertisement, which they published in a Chinese daily. Such glaring mistakes are simply unacceptable.

For those who are unaware, this Lunar New Year waves goodbye to the Year of the Rooster, and ushers in the Year of the Dog.

As the dog is considered “haram” [VHM: forbidden or proscribed] in some Islamic circles, it is possible that a decision had been made to air-brush all photos and references to the animal, in the Domestic Trade, Cooperatives and Consumerism Ministry (KPDNKK) adverts. The ministry published a picture of a rooster, barking “Wang! Wang!”

The rooster in the advertisement is crowing "wàng! wàng! 旺! 旺!"

Wait a minute! They've used the wrong character.

They should have written "wāngwāng 汪汪", which is the sound of a dog's bark in Chinese, and it has been written that way since the Yuan period (1271-1368).

When not used onomatopoetically for the sound of a dog barking, wāngwāng 汪汪 can indicate "profuse (tears)" or "vast (water)".

Wàng 旺, on the other hand, means "flourishing; prosperous; vigorous".

Here's what a live barking rooster looks and sounds like ("Ronnie the barking rooster"):

And here's a crowing dog:

This dog tries very hard to say "cock-a-doodle-doo!":

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o6rCQzbrp-g

Now, after all that fun, I'll have to serve up a more philologically serious post on the words for dog in Sinitic, which I will do within a day or two.

[h.t. Jichang Lulu]

Bathrobe said,

February 18, 2018 @ 8:27 pm

I received new year messages using 旺旺.

Victor Mair said,

February 18, 2018 @ 10:42 pm

The expression "gǒunián wàngwàng 狗年旺旺" ("[may] the year of the dog be prosperous") is ubiquitous at the dawning of this new year. Indeed, the zhāocái gǒu 招财狗 ("dog that brings wealth / treasure") is one form of the "zhāocái shén 招财神" ("god that brings wealth / treasure") or just "cáishén 财神" ("god of wealth").

By having the rooster in the newspaper ad cry ""wàng! wàng! 旺! 旺!" ("posperity! prosperity!), the designers are punning on wāngwāng 汪汪 ("bow wow").

Thanks for helping me bring that out, Bathrobe.

Victor Mair said,

February 18, 2018 @ 10:44 pm

From Chen Sanping:

This year 旺 is widely used in Chinese New Year greetings as a near-homophone of 汪, signifying of course "prosper, getting rich," the new popular religion in mainland China..

ajay said,

February 19, 2018 @ 6:55 am

I wonder if this policy extends to other animals. Because it strikes me that the Chinese calendar contains quite a few haram years; the year of the Pig, most obviously, but I believe that snakes are also haram, as are rats, tigers and monkeys, and, I would imagine, dragons. That's eight out of twelve!

Vulcan With a Mullet said,

February 19, 2018 @ 10:00 am

"Imagine dragons" are definitely haram as they are an indie band.

J.W. Brewer said,

February 19, 2018 @ 11:21 am

There's a scholarly article out there called "The Chinese-Uighur Animal Calendar in Persian Historiography of the Mongol Period," and someone must have studied how, as the 12-year-cycle came into use by various peoples along the Silk Road who had Chinese cultural influence coming at them from one direction and Islam coming at them from the other, the specific animals were or were not changed to accommodate Muslim preferences and sensibilities. To ajay's point, I would speculate that perhaps not all "haram" animals are viewed negatively from an Islamic perspective (bracketing the question of the no doubt considerable variation across time and place within the vast and heterogenous Muslim world), just as e.g. in traditional Jewish culture the lion is equally non-kosher as the pig when it comes to the question of human consumption of its meat but is viewed more favorably than the pig for symbolic use in non-culinary contexts.

ajay said,

February 19, 2018 @ 11:26 am

"Imagine dragons" are definitely haram as they are an indie band.

And very few if any Islamic scholars endorse the eating of indie musicians.

Nick Kaldis said,

February 19, 2018 @ 12:14 pm

One of the most well-known associations between a creature and the "Weng1" sound, for many Chinese speakers (esp. in Taiwan), would be that of a buzzing/flying bee, from the animated (Japanese) children's TV series of the 1970s, 《小蜜蜂》, which began with a now-famous theme song: "有一個小蜜蜂飛到西又飛到東 嗡嗡嗡嗡嗡嗡嗡 不怕雨也不怕風..". Versions of the song appear on many children's music CDs as well.

Su-Chong Lim said,

February 20, 2018 @ 12:17 am

@Chen Shaiping:

"the new popular religion in mainland China.."

Hmmm, I would beg to differ — maybe the actual acquisition of significant middle class wealth is recent, but the fixation on and desire for wealth in China is not new but has been steeped in the culture for ages.

恭喜發財 is not a startlingly new-age New Year greeting, but has been expressed by well-wishers for generations, if not for ever as far as I know!

Victor Mair said,

February 22, 2018 @ 1:12 pm

From David Morgan

@J. W. Brewer

I'm familiar with this article (by Charles Melville: Iran, XXXII, 1994, pp. 83-98). Its original appearance was as a paper at a conference at SOAS which I organised in 1991. Looking again at the article, it doesn't seem to make any reference to the issue discussed below. For example, I can't see any reference to "Pig" disappearing! But Melville does remark that Rashid al-Din, while he gives animal dates as well as Hijri ones for most of his chronicle, stops doing so for the reign of Ghazan (1295-1304), the first of the uninterrupted line of Muslim Ilkhans, which might be significant – though they return in Qashani's chronicle of the reign of Ghazan's successor Oljeitu (perhaps linked to what seems to have been something of an anti-Islamic reaction among the Mongol notables at the start of that reign?)