Dumpling ingredients and character amnesia, part 2

This post follows in the path of its classic predecessor, "Dumpling ingredients and character amnesia" (10/18/14), must see. Here we begin with this provisions list:

Read the rest of this entry »

This post follows in the path of its classic predecessor, "Dumpling ingredients and character amnesia" (10/18/14), must see. Here we begin with this provisions list:

Read the rest of this entry »

A recent blog on Miao/Hmong posted on Language Log reminded Chau Wu of an earlier news report from Taiwan about a 5th grade girl from Hla'alua (Lā'ālǔwa zú 拉阿魯哇族) who won a speech competition using her native language (article in Chinese).

"With fewer than 10 native speakers and an ethnic population of 400 people, Saaroa (= Hla'alua) is considered critically endangered," according to the article on Saaroa language in Wikipedia.

Read the rest of this entry »

We have often experienced vexation and consternation over the future of Taiwanese / Hoklo, especially in light of what's happening to Cantonese in the PRC. Now comes some welcome news from Ilha Formosa. A renewal of Taiwanese has recently been spurred by a least expected source, China.

Chinese Pressure Fuels an Unlikely Language Revival in Taiwan:

Local tongues gain popularity as more people on the self-ruled island, where Mandarin predominates, disavow their connection with China

By Joyu Wang, WSJ (12/22/21)

Pranav Mulgund remarks:

A recent aversion to the CCP has pushed people in Taiwan to stop speaking Mandarin. For instance, “One enthusiastic participant is Lala Sin, a 35-year-old mother of three, who has largely avoided speaking Mandarin Chinese, the most used language in both Taiwan and China, since last winter, instead talking with her children exclusively in Taiwanese Hokkien, or Taigi (pronounced 'dye-ghee')”. Teachers of the language have experienced a tripling in enrollment from 2012 to 2020. I think it’s quite an interesting idea to revolt through language. It’s obviously not an unprecedented idea, but quite fascinating to happen in modern times.

Read the rest of this entry »

Article in South China Morning Post (12/18/21):

My Hong Kong by Luisa Tam

Cantonese is far from dead. It lags Mandarin in the Chinese language league table for numbers, but its cult status will see it live on

Cantonese is a one-of-a-kind linguistic art form that’s quirkier and more edgy than Mandarin, nimble and ever-changing

Its long-term fate is in the hands of every Cantonese speaker and Cantonese-language enthusiast who is willing to continue to breathe new life into it

In this, her most recent article on the nature and fate of Cantonese, Luisa Tam, a favorite author of ours here at Language Log, is upbeat about the future of the language. I love Cantonese as much as she / anyone does, but I am less sanguine about what lies ahead for it than Luisa is. As I said several days ago during a faculty meeting at Penn, there's no one who is more passionate about about defending and promoting Cantonese than VHM. Why, then, am I so pessimistic about what is in store for this lively language?

Before I answer that question, let's see why Luisa Tam is so positive about Cantonese in the coming years. Here are some selections from her article:

Read the rest of this entry »

Article by Rhoda Kwan, Hong Kong Free Press (31/10/21):

‘The loss of language is the loss of heritage:’ the push to revive Taiwanese in Taiwan

"You can't completely express Taiwanese culture with Mandarin – something is bound to be lost in translation," says one advocate for the local language.

When I go to Taipei, I seldom hear Taiwanese being spoken, especially by people under forty or fifty. That is always saddening to me, especially considering the fact that about 70% of the total population of Taiwan today are Hoklos.

…

The rare usage of Taiwanese, particularly on the streets of its capital Taipei, is a legacy of decades of colonial rule. During 50 years under Japanese rule, and the Kuomintang’s subsequent martial law from 1949 to 1987, generations of Taiwanese were banned from speaking their mother tongue in public.

“A whole generation’s learning in this language was washed away, and with this language a culture and identity was also washed away,” said Lí Sì–goe̍h, a Taiwanese language advocate.

Before the arrival of the Kuomintang, Taiwanese – a language from China’s Fujian province also referred to as Taigí, Taiwanese Hokkien, Hoklo or Southern Min – was spoken by most Han immigrants who arrived on the island from the 17th century onwards. Other languages, including other Chinese languages such as Hakka and dozens of different Austronesian indigenous languages, were also spoken on the island, a reflection of the diversity of ethnic groups that have lived on the island for centuries.

Read the rest of this entry »

In Asian Review of Books (10/20/21), Peter Gordon reviews James Griffiths' Speak Not: Empire, Identity and the Politics of Language (Bloomsbury, October 2021). Although the book touches upon many other languages, its main focus is on Welsh, Hawaiian, and Cantonese.

…

That Speak Not is more politics than linguistics is telegraphed by the title. For Griffiths, language is the single most important aspect of group identity, both as marker and glue: that what makes the Welsh Welsh or Hawaiians Hawaiian is primarily the language, rather than lineage, culture, belief systems or lifestyles. While some might debate this, governments have all too often taken aim at minority languages with precisely this rationale in the name of national unity.

Read the rest of this entry »

A little over a week ago, someone out of the blue called to my attention a discussion on a major social media platform about Sibe language and its alleged three writing systems: "Old Uyghur alphabet, Latin alphabet, and Japanese-style system". Apparently, parts of the original post were removed by the moderators because they were thought to be politically or otherwise controversial. Colleagues who are knowledgeable about such matters advised me that the thread in question represents a potential computer security risk, so I am not referring to it directly.

In any event, Sibe — with a population of less than two hundred thousand — is back in the news, and has considerable significance in various dimensions out of all proportion to its numbers. Consequently, especially since not too long ago we had a lively discussion about Sibe here on Language Log, I thought it might be worthwhile to review some of the basic facts about this enigmatic language.

Read the rest of this entry »

The linguistic importance of Dungan is greatly disproportionate to the number of its speakers, approximately 150,000, who live in seven different countries that are widely spread across Eurasia: Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Russia, Tajikistan, Mongolia, Uzbekistan, and Ukraine. The main reason why Dungan has been the focus of so much interest during the half-century since I began studying this fascinating language is that it puts the lie to the fallacy that Sinitic languages can only be written with the Sinographic script (i.e., Chinese characters). The only Sinitic language that needs to be written with morphosyllabic characters is Literary Sinitic / Classical Chinese, a language that, in terms of its sayability, has been dead for millennia. The recent academic study of Dungan has played a key role in enabling language specialists and the lay public finally to come to this realization.

Because the Dungan people are so highly scattered across vast distances and live among dominant populations with completely different languages that they need to speak for daily survival, their own language — and consequently also its alphabetic script — is threatened with extinction. Furthermore, in recent decades the Dungans have been buffetted by ethnopolitical winds that make it even harder to maintain their unique identity. That is why I have long felt a sense of urgency about the need to document and research Dungan language and script in all of their dimensions (morphology, phonology, lexicography, grammar, syntax, script, literature, sociolinguistics…).

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink Comments off

The question of language survival in Taiwan is far more complex than whether Taiwanese (and Hakka and Cantonese) will die at the hands of Mandarin. Helen Davidson probes the real situation in:

"Healing words: Taiwan’s tribes fight to save their disappearing languages

The island’s Indigenous people are in a race against time to save their native tongues before they are lost forever"

Guardian (6/8/21)

The author introduces us to Panu Kapamumu, speaker and guardian of his native language, Thao / Ngan. Right away, we come up against a thorny thicket of linguistic verities: "Normally, Kapamumu speaks in a mix of the two languages he knows better than his own – Chinese and English."

Read the rest of this entry »

Essay in Wall Street Journal:

"Computers Speaking Icelandic Could Save the Language From ‘Stafrænn Dauði’ (That’s Icelandic for ‘Digital Death’): To counter the dominance of English in technology and media, Iceland is teaching apps and devices to speak its native language." By Egill Bjarnason (May 20, 2021).

This is such a fascinating article, and one that points to a gigantic problem of language survival for many of the world's roughly 7,000 remaining tongues, that I could easily quote the entire piece. I will resist that temptation, but will still offer generous chunks of it. One part of the story that I cannot forgo is the saga of Snorri Sturluson (1179-1241) and his epic linguistic and literary legacy.

Telma Brigisdottir, a middle-school teacher in suburban Iceland, arrived at her classroom on a recent morning in March eager to introduce a new assignment. Dressed in a pink hoodie, she told her students: Turn on your iPad, log into the website Samromur, and read aloud the text that appears on screen. Do this sentence after sentence after sentence, she instructed, and something remarkable will happen. The computer will learn to reply in Icelandic. Eventually.

Read the rest of this entry »

Persuasive 14:09 YouTube video of Aiong Taigi explaining why he doesn't use Chinese characters (Hàn-jī 漢字) on his channel, but instead sticks to Romanization (Lomaji) as much as possible: A'ióng, lí sī án-chóaⁿ bô teh ēng Hàn-jī? 【阿勇,汝是安盞無塊用漢字?】:

Read the rest of this entry »

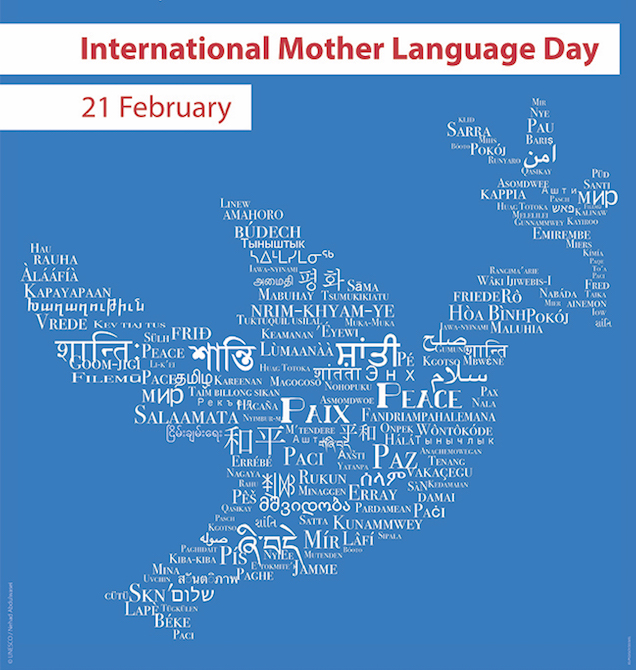

February 21st is International Mother Language Day, proclaimed by the General Conference of UNESCO in 1999 and celebrated every year since, aimed at promoting linguistic and cultural diversity and multilingualism. In honor of the day, the following is a guest post by Alissa Stern, the founder of BASAbali, an initiative of “linguists, anthropologists, students, and laypeople, from within and outside of Bali, who are collaborating to keep Balinese strong and sustainable.” BASAbali won a 2019 UNESCO Award for Literacy and a 2018 International Linguapax Award.

February 21st is International Mother Language Day, proclaimed by the General Conference of UNESCO in 1999 and celebrated every year since, aimed at promoting linguistic and cultural diversity and multilingualism. In honor of the day, the following is a guest post by Alissa Stern, the founder of BASAbali, an initiative of “linguists, anthropologists, students, and laypeople, from within and outside of Bali, who are collaborating to keep Balinese strong and sustainable.” BASAbali won a 2019 UNESCO Award for Literacy and a 2018 International Linguapax Award.

We’re told “Don’t wait” to treat our bodies, secure our homes, or maintain our cars. We should do the same for local languages.

Despite all the years of language revitalization, we are still losing about one language every two to three weeks. In this century alone, the number of languages on the planet will be halved. A little preventive care would help.

Read the rest of this entry »