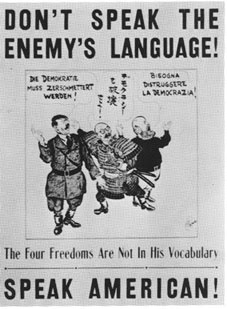

DON'T SPEAK THE ENEMY'S LANGUAGE!

This World War II American propaganda poster speaks for itself:

A poster of WWII era discouraging the

use of Italian, German, and Japanese.

(Source)

Read the rest of this entry »

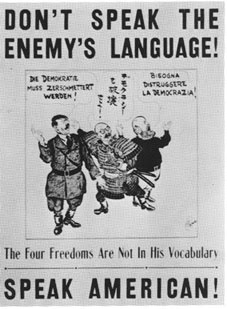

This World War II American propaganda poster speaks for itself:

A poster of WWII era discouraging the

use of Italian, German, and Japanese.

(Source)

Read the rest of this entry »

I am fond of this expression and have often wondered how it arose. In my own mind, I have always associated it with the hissing of a cat and hysteria, but never took the time to try to figure out where it really came from. Today someone directly asked me about the origins of this quaint expression and proposed a novel solution, which I will present at the end of this post. First, however, let's look at current surmises concerning the problem.

Read the rest of this entry »

The following three items might well have been included in the previous post on Chinglish, but that one got to be rather long and unwieldy, so I'm treating these separately. In any event, I think that they merit the special treatment they are receiving here.

Read the rest of this entry »

I'm prompted to ask this question in response to the very first comment on this post:

"'Butterfly' words as a source of etymological confusion" (1/28/16)

The comment supplies a link to this YouTube video, in which russianracehorse tells "The Butterfly Joke". A Frenchman, an Italian, a Spaniard, and a German each pronounce the word for "butterfly" in their own language. The words for "butterfly" in the first three languages all sound soft, delicate, and mellifluous. Finally the German chimes in and shouts vehemently, "Und vat's wrong with [the joke teller could have said 'mit'] Schmetterling?"

Read the rest of this entry »

Nick Kaldis writes:

I've started buying English etymology books for my 8-year-old daughter and I to explore; today we discovered that "butterfly" comes from "butter" + "shit", because their feces resemble butter.

Read the rest of this entry »

In "Shampoo salmon" (2/10/14), I called attention to the variety of opinions concerning the origins of the Chinese word bōluó 菠萝 / variant bōluó 波萝 ("pineapple"). Tom Nguyen suggests that another possible source is from Old Vietnamese *bla (> dứa /z̻ɨ̞̠ɜ˧ˀ˦/ with Northern accent – note the process of “turning into sibilant” of initial consonant cluster bl- in Vietnamese).

Read the rest of this entry »

From Matthew Yglesias:

A few of us at work were talking about why it's adviser and protester but professor and and auditor and after bullshitting around for 10 minutes I thought "maybe I should ask a linguist." Have you ever blogged on this?

I don't think that we have, though you can find well-informed discussions elsewhere, e.g. here or here/here. The executive summary is that -er is (originally) Germanic while -or is (basically) Latin, often via French.

But this doesn't help much with the particular examples you cite, since all four words are from Latin via French. Like most things about English morphology and spelling, the full answer is complicated, and also more geological than logical. But the OED seems to have the whole story — lifted from the depths of the discussion, the key point is that

Many derivatives [formed with -er as an agentive suffix] existed already in Old English, and many more have been added in the later periods of the language. In modern English they may be formed on all vbs., excepting some of those which have [Latin- or French-derived] agent nouns ending in -or, and some others for which this function is served by ns. of different formation (e.g. correspond, correspondent). The distinction between -er and -or as the ending of agent nouns is purely historical and orthographical.

For a (much) longer treatment — you have been warned — press onward.

Read the rest of this entry »

Peter Reitan, previously involved in "Solving the mystery of 'off the cuff'" (2/21/2015), has now pointed us to an improved history of monkey wrench. His email:

Your Language Log post of March 22, 2009 about "Monkey Wrench" mentioned the traditional folk-etymology associated with the term; namely that it was widely believed to have been invented by a "London Blacksmith who invented an adjustable wrench." All of the early recitations of that folk-etymology (early 1880s), however, attribute the wrench to Charles Moncky, said to have sold his invention for $2000 and to then be living in a small cottage in Brooklyn, New York.

Surprisingly, perhaps, the 1880 census for Brooklyn, New York reports a man named Charles Monk – "tool-maker "- living on Sixteenth Street in Brooklyn. He may have inspired the folk-etymology; but he does not appear to have invented, inspired, or coined the "monkey wrench." He was only twelve years old when the earliest-known, date-certain references for "monkey wrench" were published in 1840: See Peter Jensen Brown, "Charles Monk, Monkey Wrenches and 'Monkey on a Stick' – a Gripping History and Etymology of 'Monkey Wrench'", 10/14/2015.

Read the whole thing.

A question from Mark Seidenberg:

Is the English phono- morpheme etymologically related to Phoenicia/Phoenician, i.e., the corresponding Phoenician words?

I have looked at the OED and other sources and I cannot connect the dots.

The Phoenician word for “Phoenicia” has a couple of conjectured etymological bases unrelated to sound or voice.

The Greeks then had a word (morpheme?) phono that was related to sound/voice, which English and other languages absorbed.

Is it a coincidence that the Greek word happened to sound like name for the language whose writing system they borrowed, the inadequacies of which for representing the typologically distinct Greek language led to the identification of vowels, which could then be written by repurposing letters for a few consonants that occurred in P but not G. or so they say.

Is this an homage to Phoenicia or are these false phonological cognates?

Read the rest of this entry »

Ben Zimmer mentioned to me that he was on the Slate podcast Lexicon Valley talking about the origins of the word "gringo":

Read the rest of this entry »

From Bob Ladd:

I just drove through the general area of Luxembourg/Lorraine – one of the places where French and Germanic have been in close contact since the Middle Ages – and could couldn't help noticing dozens of place names ending in -ange (Dudelange, Hettange, Differdange, Hayange, Hagondange, Aubange, Redange, Useldange, and many more) all within a relatively small area. I've tried to come up with some Germanic town name component that could have been gallicized as -ange, but I've drawn a blank. Does any reader know the source of these names?

Read the rest of this entry »

The exoticization of Chinese, yet again

This time it's the alleged, essential aqueousness of governance:

"The Water Book by Alok Jha review – this remarkable substance", by Rose George (5/14/15). The first sentence: "The Chinese symbol for 'political order' is made from the characters for river and dyke."

What a lame, wrongheaded way to begin a serious article!

Read the rest of this entry »