In reading texts from the earliest times of Chinese writing up to the present, and at all social levels and linguistic registers, I have noticed a curious phenomenon. Namely, often an overtly negative particle or term will have no privative or prohibitive force, but is simply there for rhythmic, clitic, or rhetorical function.

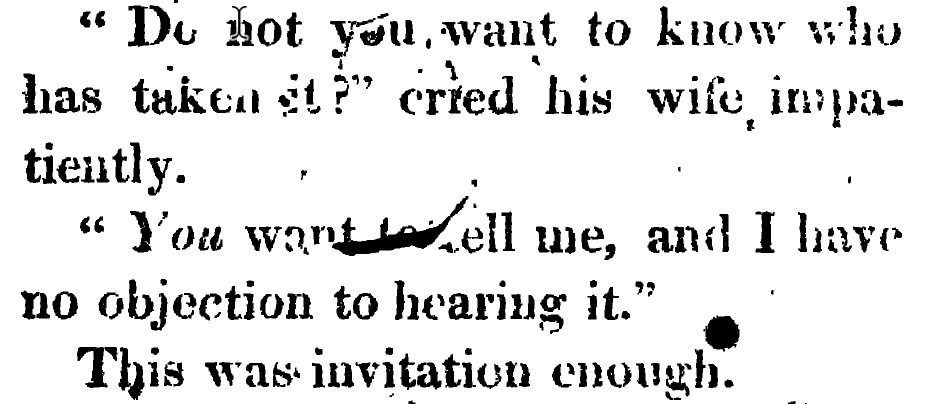

Naturally, since negation is normally marked and unmistakable in its purpose, when its unaffirmative function is lost / absent / missing, interpreting the intended meaning of such a statement or utterance can be challenging.

I was prompted to contemplate this curious phenomenon when I was writing a message to my brother in Chinese, and realized that "guǎn tā 管它" and "béng guǎn tā 甭管它" mean the same thing: — "forget about it; leave it alone; don't worry about it"! — with or without the negative word being overtly present.

Read the rest of this entry »