Archive for Language teaching and learning

"…her eyes began to swell in tears when she was asked to take out the Mandarin work sheets…"

The following post is from an old, now defunct, blog, but the description of little Eunice learning three languages at once (none of which was her natal tongue spoken at home) and other discussions of Chinese are unusual in their detail and sensitivity, so worthy of sharing with Language Log readers:

"Primary learning in a multilingual society ", Grammar Gang (5/24/14)

The author of the post is Jyh Wee Sew (Centre for Language Studies, Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences, National University of Singapore). I will simply quote a few passages of the post and make a few concluding remarks, but warmly recommend that anyone who is interested in second (and third) language pedagogy / acquisition read the whole post.

Read the rest of this entry »

Imperial miscommunication

[This is a guest post by Krista Ryu]

I came across a fun anecdote from The Annals of the Joseon Dynasty, which is the annual records of the Joseon Dynasty from 1413-1865, a national treasure of Korea. It is full of interesting, authentic records, since no one, including the kings themselves, could revise the records. Consequently, even funny mistakes made by the Kings will be recorded in detail.

The story of failed communication between a Goryo Dynasty diplomat and the Hongwu Emperor (1368-1398; r. 1328-1398) of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

The story is as below (I have translated into English what I read in Korean, so what was actually said in Chinese at the time could be slightly different but the meaning should be the same):

Read the rest of this entry »

Learning languages is so much easier now

If you use the right tools, that is, as explained in this Twitter thread from Taylor ("Language") Jones.

A brief thread on how kids have it (in this case, language learning) easier these days.

When I first studied Chinese in college… 1/

— Language Jones (@languagejones) August 17, 2017

Rule number 1: Use all the electronic tools at your disposal.

Rule number 2: Do not use paper dictionaries.

Jones' Tweetstorm started when he was trying to figure out the meaning of shāngchǎng 商场 in Chinese. He remembered from his early learning that it was something like "mall; store; market; bazaar". That led him to gòuwù zhòngxīn 购物中心 ("shopping center"). With his electronic resources, he could hear these terms pronounced, could find them used in example sentences, and could locate actual places on the map designated with these terms.

Read the rest of this entry »

Chinese, Greek, and Latin, part 2

[This is a guest post by Richard Lynn. It is all the more appreciated, since he had written it as a comment to "Chinese, Greek, and Latin" (8/8/17) a day or two ago, but when he pressed the "submit" button, his comment evaporated. So he had to write the whole thing all over again. I am grateful to Dick for his willingness to do so and think that the stimulating results are worth the effort he put into this post.]

James Zainaldin’s remarks concerning the Lunyu, Mencius, Mozi, Zhuangzi, and the Dao de jing, his frustration by the limits of grammatical or lexical analysis, that is, the relative lack of grammatical and lexical explicitness compared to Greek and Latin texts, is a reasonable conclusion — besides that, Greek and Latin, Sanskrit too, all are written with phonetic scripts — easy stuff! But such observations are a good place to start a discussion of the role of commentaries and philological approaches to reading and translating Literary/Classical Chinese texts, Literary Sinitic (LS). Nathan Vedal’s remarks are also spot on: “LS is really an umbrella term for a set of languages. The modes of expression in various genres and fields differ to such a high degree that I sometimes feel as though I'm learning a new language when I begin work on a new topic.”

Read the rest of this entry »

Chinese, Greek, and Latin

More than a year ago, I made this post:

"Which is harder: Western classical languages or Chinese?" (3/6/16)

In that post, I described a sense of anxiety that seems to pervade the venerable discipline of philology, which seemed to be in the process of morphing into something called "Classical Studies". This feeling of uncertainty about the future of our scholarly disciplines was (and is) true both of Sinology and of Greek and Latin learning. (See also "Philology and Sinology" [4/20/14].)

In last year's post, I highlighted an essay by Kathleen Coleman on the blog of the Society for Classical Studies (SCS): "Nondum Arabes Seresque rogant: Classics Looks East" (2/2/16). Coleman describes how she asked one of her graduate students, James Zainaldin, who was learning Chinese (evidently Mandarin) at the time to compare his experience with that language to what he had experienced learning Greek and Latin. I remember thinking at the time that Professor Coleman was expecting quite a lot from James, since learning Modern Standard Mandarin (MSM) and learning Literary Sinitic / Classical Chinese (LS / CC) were two very different tasks. I expressed that uneasiness with the task that Professor Coleman had set James, yet remarked that he had nonetheless made a number of significant observations.

Read the rest of this entry »

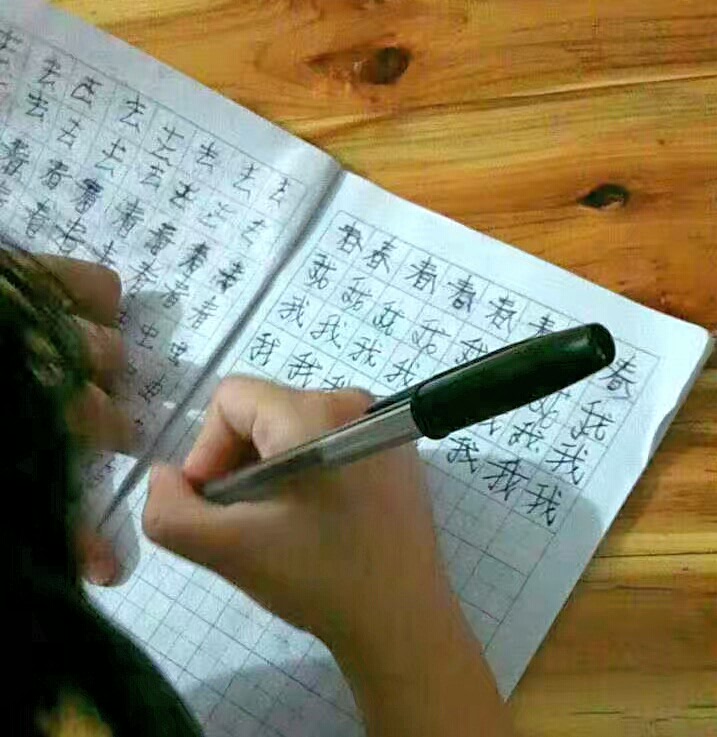

Learning to write Chinese characters

Following on yesterday's post ("The naturalness of emerging digraphia" [7/28/17]), Alex Wang tells me, "parents and supplementary educators often post photos like these on their WeChat moments". Here's an example of one that he sent along:

Read the rest of this entry »

Listening, speaking, dissing, and writing

The four main aspects of learning a language are "tīng shuō dú xiě 听说读写 (simplified) / 聽說讀寫 (traditional) ("listening, speaking, reading, and writing"). A few days ago in Singapore, an event was held to promote Mandarin in accordance with this fourfold approach. Unfortunately, at the launch of the campaign on July 10, 2017, on the front of the large podium behind which stood the four guests of honor, this slogan was miswritten in simplified characters as tīng shuō dú xiě 听说渎写, where the third character has a water radical / semantophore instead of the speech radical / semantophore. The pronunciation of the two characters is identical, but there's a world of difference in their meaning.

Read the rest of this entry »

White dude challenges Chinese speakers in Shanghai

Jayme, his gangling arms covered with colorful tattoos, sallies forth onto Nanjing Road, the busiest shopping street in Shanghai, and tests the local denizens and tourists on their language skills (reading, writing, and pronunciation):

Read the rest of this entry »

How not to learn Chinese

In "Sinological suffering" (3/31/17), "Aphantasia — absence of the mind's eye" (3/24/17), and other recent posts, we examined the difficulty, for some the near impossibility, of mastering how to write hundreds and thousands of Chinese characters. Yet, if one wishes to become literate in Chinese, one simply must do it. Until the 21st century, there was basically only one way: rote copying of the characters to engrave them in the neuromuscular pathways of the learner.

Read the rest of this entry »

The miracle of reading and writing Chinese characters

We have the testimony of a colleague whose ability to write Chinese characters has been adversely affected by her not being able to visualize them in her mind's eye. See:

"Aphantasia — absence of the mind's eye" (3/24/17)

This prompts me to ponder: just how do people who are literate in Chinese characters recall them?

Read the rest of this entry »

Difficult languages and easy languages

People often ask me questions like these:

What's the easiest / hardest language you ever learned?

Isn't Chinese really difficult?

Which is harder, Chinese or Japanese? Sanskrit or German?

Without a moment's hesitation, I always reply that Mandarin is the easiest spoken language I have learned and that Chinese is the most difficult written language I have learned. I learned to speak Mandarin fluently within about a year, but I've been studying written Chinese for half a century and it's still an enormous challenge. I'm sure that I'll never master it even if I live to be as old as Zhou Youguang.

Read the rest of this entry »