Archive for Language and technology

July 13, 2012 @ 2:40 pm· Filed by Geoffrey K. Pullum under Language and technology, Philosophy of Language

To my considerable astonishment I read this in a piece of boilerplate automatically tacked onto the end of an email reply that I received when I emailed my personal contact person and account manager at my bank:

This message originated from the Internet. Its originator may or may not be who they claim to be and the information contained in the message and any attachments may or may not be accurate.

I can't see anything in it that is actually incorrect (and I like the use of singular they); it just seems extraordinary to receive a sort of endorsement of global skepticism from one's bank. My philosophical friends tend to have no time at all for global skepticism of this sort. They would ask the sender, "Should we therefore not assume that this caveat is accurate? Should we doubt that it originated from the Internet, since the sentence saying so did?" And eventually the sender would vanish in a puff of logic.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

July 5, 2012 @ 1:50 pm· Filed by Geoffrey K. Pullum under Language and technology, Lost in translation

In the bathroom at a friend's house tonight I saw, on the underside of the toilet lid, firmly affixed with adhesive, a printed paper sign that I truly do not understand. That is, although I comprehend it (it is in six languages, all of which I read well enough to be able to follow the legend in question), I don't follow what its purpose could possibly be. I am truly baffled. Let me show you what it said. Keep in mind that the following is all of what it says. Nothing is missing from the label, and there is no other wording at all (and incidentally, the various accent mistakes are not mine, they are copied from the original). See if you are as baffled as I am:

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

June 22, 2012 @ 6:28 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Etymology, Language and technology

From a correspondent in Taiwan who wishes to remain anonymous:

Sometimes the word 'taikonaut' will be seen in news articles about PRC astronauts. This cuto-chinoiserie is really stupid. The premise seems to be that since Russian astronauts are called cosmonauts, PRC astronauts ought to have a special name too.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

June 18, 2012 @ 10:09 am· Filed by Geoffrey K. Pullum under Language and technology, Silliness

Perhaps it is because I'm at the Computability in Europe 2012 conference, a big meeting honoring the centenary of Alan Turing's birth, that I was reflecting on algorithms today. My phone answering machine at home is programmed to count the number of messages waiting to be listened to, storing the total in a variable I will call N, and then set another variable that I will call M to the initial value of 1; and the playback button causes the running of a routine of which the pseudo-code would be this:

if N = 1

speak "You have one new message."

else

speak "You have N new messages."

end if

for each M from 1 to N

speak "Message M:"

play message M

end for

speak "End of messages."

speak "To delete all messages, press Delete."

Can you see what's so incredibly annoying here, to a linguist, or anyone with some basic common sense about pragmatics?

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

June 10, 2012 @ 11:19 am· Filed by Ben Zimmer under Errors, Language and technology

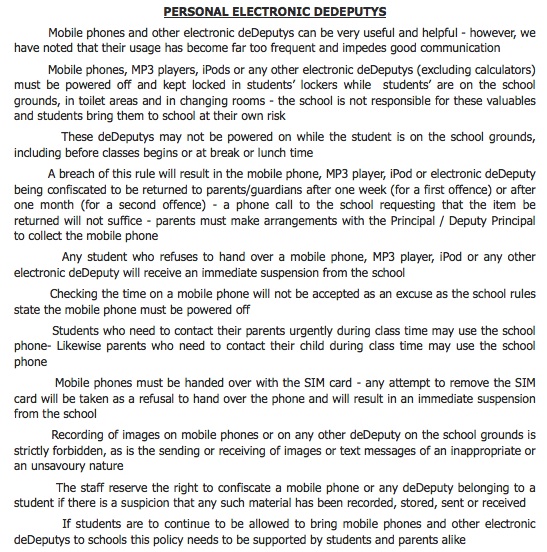

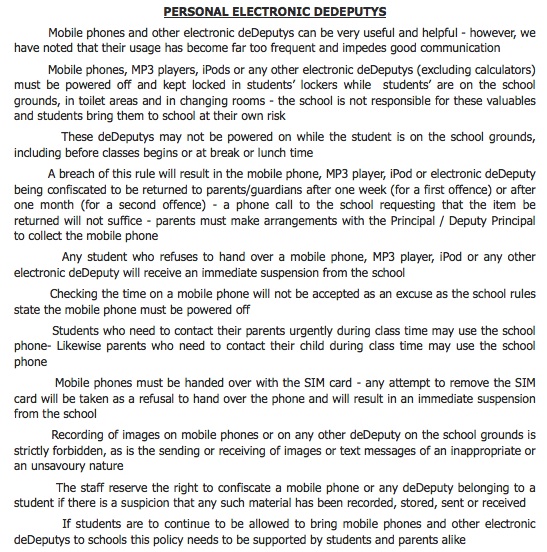

On the heels of the notorious Nooking of War and Peace, Shane Horan sends along "a priceless search-and-replace error on the rules page of an Irish secondary school." St. Joseph's College in Borrisoleigh, County Tipperary has an entire section on "personal electronic deDeputys": though "mobile phones and other electronic deDeputys can be very useful and helpful," the school's rules say "these deDeputys may not be powered on while the student is on the school grounds, including before classes begins or at break or lunch time."

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

June 1, 2012 @ 11:29 pm· Filed by Ben Zimmer under Errors, Language and technology

Here on Language Log we've often talked about unfortunate search-and-replace miscorrections, which now seem to be infecting poorly edited e-reader texts. The latest example, via Kendra Albert on Jonathan Zittrain's Future of the Internet blog, is a doozy. The Nook edition of Tolstoy's War and Peace (in its English translation) has been de-Kindled, quite literally. Every instance of the text string kindle has been replaced by Nook.

(Click to embiggen.)

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

May 2, 2012 @ 12:34 am· Filed by Ben Zimmer under Computational linguistics, Language and technology

For the past couple of years, Google has provided automatic captioning for all YouTube videos, using a speech-recognition system similar to the one that creates transcriptions for Google Voice messages. It's certainly a boon to the deaf and hearing-impaired. But as with Google's other ventures in natural language processing (notably Google Translate), this is imperfect technology that is gradually becoming less imperfect over time. In the meantime, however, the imperfections can be quite entertaining.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

April 11, 2012 @ 4:13 pm· Filed by Ben Zimmer under Errors, Language and technology, Language and the media

A correction from The New York Times on Damon Darlin's article, "Economic Theory Plots a Course for Good Food" (4/10/12 online, p. D3 in the 4/11/12 print edition):

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction:

Correction: April 10, 2012

An earlier version of this article incorrectly referred to the Ethiopian dish doro wot as door wot. Additionally, the article referred incorrectly to awaze tibs as aware ties.

As noted on the Slate Twitter feed, these goofs are almost certainly the result of overzealous autocorrect — or, as we say in these parts, they're due to the Cupertino effect. We've documented many such cupertinos over the years (old site, new site). Foreign food terms have cropped up before — way back in 2005, before we even knew the Cupertino effect had a name, I noted that menus and recipes had fallen prey to the unfortunate spellcheck miscorrection of prostitute for prosciutto. At least prosciutto is likely to be in spellcheck dictionaries these days — the same can't be said for Ethiopian doro wot or awaze tibs, no matter how delectable those dishes may be.

(Craig Silverman of Poynter's Regret the Error is also on the case.)

Permalink

January 29, 2012 @ 9:49 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and technology, Lost in translation

Carley De Rosa spotted this sign in the Kunming airport on her way to Laos. Dumbfounded by the Chinglish, not least because what it called an "elevator" was actually an "escalator", on her way back from Laos she made sure to get a photograph of the sign and send it to me for analysis:

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

January 23, 2012 @ 3:36 am· Filed by Geoffrey K. Pullum under Language and technology, Logic, Lost in translation, Nerdview, Semantics

In the Hotel Ciutat de Tarragona, the beautiful modern hotel in Tarragona where I am currently staying, I ate breakfast in the 1st-floor restaurant (Americans: that would be the 2nd floor), and then came out to take the elevator back up to my 5th-floor room (Americans: 6 floors up). But I was baffled: there was no button to call the elevator for upward journeys. There was just a button labeled with the Down-Arrow symbol for calling the elevator to go back down to the lobby on level 0. Some sort of security, I assumed, to ensure that random restaurant patrons don't go up in the elevator to wander up and down the halls looking for unlocked doors or stealable items. But then how was I to get back up to my room? I'm ashamed to report just how long it took me to resolve the conundrum here. Perhaps you would like to solve it for yourself before you read on.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

December 11, 2011 @ 12:58 pm· Filed by Geoffrey K. Pullum under Idioms, Language and technology, Language change

Throughout my whole life it has been the standard British English metaphor for Sisyphean tasks, the jobs that are endless because by the time you get to the end you need to start over: It's like painting the Forth Bridge.

Throughout my whole life it has been the standard British English metaphor for Sisyphean tasks, the jobs that are endless because by the time you get to the end you need to start over: It's like painting the Forth Bridge.

It is legendary that after finishing the magnificent rail bridge over the Firth of Forth north-west of Edinburgh in 1890 they started repainting it, and a hundred years later they were still at it. Every time they painted their way to the far end, which took years, the paint had worn off where they had started, and they had to go back over there and begin again immediately.

But there was a new development this week: they finally finished the job, and stopped. Now the simile's future looks bleak.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

October 30, 2011 @ 6:27 pm· Filed by Ben Zimmer under Computational linguistics, Language and technology, Language on the internets

I have a piece in today's New York Times Sunday Review section, "Twitterology: A New Science?" In the limited space I had, I tried to give a taste of what research is currently out there using Twitter to build various types of linguistic corpora. Obviously, there's a lot more that could be said about these projects and other fascinating ones currently underway. Herewith a few notes.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

October 30, 2011 @ 4:29 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and technology, Writing systems

Michael Carr writes, "While examining an iPhone dictionary app (KanjiDicPro), I got a laugh from the attached "bǐshùn biānhào' 笔顺编号." [VHM: bǐshùn biānhào' 笔顺编号 means "stroke order serial/code number"]

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

Throughout my whole life it has been the standard British English metaphor for Sisyphean tasks, the jobs that are endless because by the time you get to the end you need to start over: It's like painting the Forth Bridge.

Throughout my whole life it has been the standard British English metaphor for Sisyphean tasks, the jobs that are endless because by the time you get to the end you need to start over: It's like painting the Forth Bridge.