Archive for Phonetics and phonology

Second. Best. Summer. School. Ever.

NASSLLI 2010 is a week long summer school that offers 15 superlative graduate level courses and workshops on Language, Logic and Information from leading scholars, plus pre-session tutorials to bring you up to speed. And the price is incredibly low, just $150 for the entire week if you're a student and register by May 1.

NASSLLI 2010 is a week long summer school that offers 15 superlative graduate level courses and workshops on Language, Logic and Information from leading scholars, plus pre-session tutorials to bring you up to speed. And the price is incredibly low, just $150 for the entire week if you're a student and register by May 1.

"Second best"? We'll come to that.

Read the rest of this entry »

Whither the Velar?

A few days ago, Cyndy Ning sent me this Website for learning pinyin pronunciation. It has both female and male voices which you can activate by clicking on nánshēng 男声 and nüsheng 女声 just above the initials D, E, and F at the top of the table. I also found similar tables here and here.

This is a neat tool, BUT, in playing around with it, I discovered that nearly all of the 4th tone -ANG syllables in the system come out sounding like -AN. A similar phenomenon holds true for all other 4th tone syllables ending in -NG; that includes -ENG, -IANG, -ING, -IONG, and -ONG, -UANG. This is especially the case with the male voice, where I have to strain very hard to hear even a semblance of a [ŋ] at the end, and sometimes I can't hear it at all. Mind you, this is only on the 4th tone! I can hear the final [ŋ] well enough on all of the other tones spoken by the male voice, and I can even hear it fairly well for 4th tone syllables when listening to the female voice.

Read the rest of this entry »

Where is *gaggig?

My preliminary experiments with dictionary searching suggest that English has absolutely no words with roots of forms like *bobbib, *papoop, *tettit, *doded, *keckick, *gaggig, *mimmom, *naneen, *faffiff, *sussis, etc. These are simple CVCVC shapes that do not seem to contain any un-English sequence. They aren't hard to say. In fact there is an example of a verb with the shape dVd that has a regular preterite tense: deed has the preterite deeded (as in The farmer deeded back his farm to the bank [WSJ w7_016]). But the pronounceability of deeded only makes the puzzle more acute: why are there no roots with the phonological form CiVCiVCi (where Ci is some specific consononant sounds and the V positions are filled with vowel sounds). Why? Or is the generalization perhaps wrong? Have I missed some words of the shape in question?

Of Pogue and plosives and palates

In his latest article, "Packing a Series of Pluses," New York Times tech columnist David Pogue went 1 for 2 in his phonetic terminology:

Apparently, the people in positions of power at Palm weren’t completely pleased with the plethora of P’s in the appellations “Palm Pre” and “Palm Pixi,” the app phones Palm produced for Sprint. Palm has now expanded the parade of P’s with a pair of improved products: the Palm Pre Plus and Palm Pixi Plus.

(We’ll pause while you repair your palate after all those plosives.)

Read the rest of this entry »

Drunkenness at the LSA

One of the papers that caught my eye at the just-complete LSA meeting in Baltimore was Abby Kaplan, "Articulatory reduction in intoxicated speech". Here's the abstract:

Voiceless stops are commonly voiced post-nasally and intervocalically. Such alternations are often attributed to articulatory ‘effort reduction’: a hypothesis that voiced stops are ‘easier’ in these environments. My experiment tests this hypothesis by comparing productions of intoxicated subjects with those of sober subjects, assuming that intoxicated subjects produce more ‘easy’ articulations. Intoxicated subjects did not uniformly increase voicing of post-nasal or intervocalic stops; rather, the range of voicing durations contracted for both types of stops. I conclude that considerations of effort do not straightforwardly predict post-nasal and intervocalic voicing: the traditional effort-based account of these processes must be refined.

Read the rest of this entry »

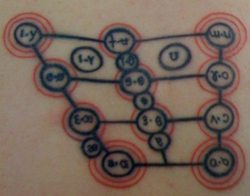

Vowel chart body art

Before I had even met American Heritage Dictionary supervising editor Steve Kleinedler, I knew about his tattoo. A 2005 New York Times article about the young Turks of American lexicography revealed that Steve "has a phonetic vowel chart tattooed across his back." Recently Steve upgraded his ink with an even more elaborate IPA chart. Since my brother Carl has supplemented his science blog The Loom with the Science Tattoo Emporium, I asked Steve to send along a shot of his new improved body art to add to the collection. Read all about it here.

Before I had even met American Heritage Dictionary supervising editor Steve Kleinedler, I knew about his tattoo. A 2005 New York Times article about the young Turks of American lexicography revealed that Steve "has a phonetic vowel chart tattooed across his back." Recently Steve upgraded his ink with an even more elaborate IPA chart. Since my brother Carl has supplemented his science blog The Loom with the Science Tattoo Emporium, I asked Steve to send along a shot of his new improved body art to add to the collection. Read all about it here.

(Also in the Emporium, there's an Aztec speech glyph, some Paiute IPA, and a glottal stop. Feel free to email Carl with photos of your own linguistic tattoos.)

Rhyming 'orange'

In the context of Mark's latest, I cannot resist telling you about the one moderately successful rhyming of orange by a poet that I know about. The poet was my friend Tom Lehrer, the mathematician / singer / songwriter / satirist / musical theater expert, who has for decades now divided his time between Cambridge MA and Santa Cruz CA. And his poem only works for those American dialects in which the first syllable of corrugated has an unrounded low back vowel (it is basically homophonous with car), and in which the last syllable in I pray to heaven above rhymes the last syllable in you're the one I'm thinking of. Check your dialect to make sure you speak that way (if you don't, then this is all wasted time for you), and if you do, here's the poem (though you'll probably complain that it cheats):

Eating an orange

While making love

Makes for bizarre enj-

oyment thereof.

Yes; I knew you would object to that line break… But be fair. It actually rhymes, if you say it right. Give credit where it's due.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink Comments off

Jingle bells, pedophile

Top story of the morning in the UK for the serious language scientist must surely be the report in The Sun concerning a children's toy mouse that is supposed to sing "Jingle bells, jingle bells" but instead sings "Pedophile, pedophile". Said one appalled mother who squeezed the mouse, "Luckily my children are too young to understand." The distributors, a company called Humatt, of Ferndown in Dorset, claims that the man in China who recorded the voice for the toy "could not pronounce certain sounds." And the singing that he recorded "was then speeded up to make it higher-pitched — distorting the result further." (A good MP3 of the result can be found here.) They have recalled the toy.

Shocked listeners to BBC Radio 4 this morning heard the presenters read this story out while collapsing with laughter. Language Log is not amused. If there was ever a more serious confluence of issues in speech technology, the Chinese language, freedom of speech, taboo language, and the protection of children, I don't know when.

Read the rest of this entry »

More excitement

In the days following my accidental Annie Lennox sighting in Edinburgh, a gorgeous picture of the honoree in her doctoral robes was published, and I have added it here; don't miss it. And (returning to phonology) Julian Bradfield (who normally studies things like fixpoint logic and concurrent programming, and teaches operating systems and programming, in Edinburgh's School of Informatics) gave a talk on the phonology and phonetics of the utterly spectacular Khoisan language sometimes known as "Taa" but more usually referred to (at least by those who can pronounce the voiceless postalveolar velaric ingressive stop [k!] followed by a high tone [o] and a nasalized [o], which Julian can) as !Xóõ (the ASCII spelling is !Xoon).

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink Comments off

Prisencolinensinainciusol

Before there was yaourter, there was Prisencolinensinainciusol, an amazing 1972 double-talk proto-rap by Adriano Celentano, channeling the Elvis of some parallel universe:

Read the rest of this entry »