Polyglot Manchu emperor

« previous post | next post »

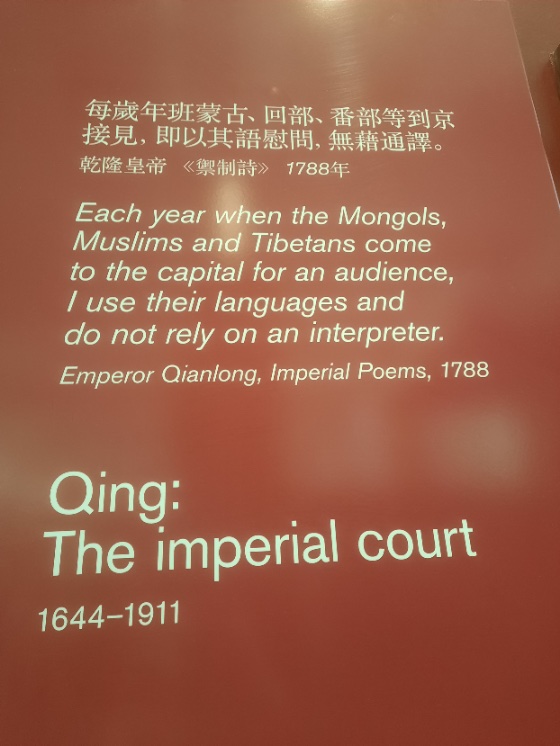

From the British Museum:

The Chinese characters say:

Měi suìnián bān Ménggǔ, Huí bù, Fān bù děng dào jīng jiējiàn, jí yǐ qí yǔ wèiwèn, wú jí tōngyì. Qiánlóng huángdì yùzhì shī

每歲年班蒙古,回部,番部等到京接見,即以其語慰問,無藉通譯。

乾隆皇帝 《御製詩》

We will start with the assumption that the English translation on the wall of the BM is serviceable, but will find, by the end of the post, that it must be radically amended and amply explicated.

If, as the translation on the wall says, the Qianlong emperor (1711-1799; r. 1735-1796), whose native language was Manchu and who was fluent in Mandarin, was able to speak with his Mongol, Muslim, and Tibetan tributaries without the need for interpreters, that would have been both impressive and convenient. But we need to look into the actual situation in a bit more detail to determine linguistically exactly what was going on. I asked a number of colleagues who are specialists in these languages for their opinions on the matter, and this is how they replied:

Chris Atwood:

Elliot Sperling noted from the biography of the Tibetan lay nobleman Doring Pandita that the Qianlong emperor talked with him in Mongolian – Tibet had been part of the Khoshud Khanate of Tibet, so Mongolian was the secular language, just as Tibetan was the religious one. David Brophy has also demonstrated how the Uyghur princes of Qumul and Turpan used for their writing a heavily Mongolized version of Chaghatay Turkic in their official documents; one may assume they too also spoke Mongolian. So, although the Qianlong emperor undoubtedly knew some religious Tibetan. it is plausible to me that he spoke to Mongols, Muslims, and Tibetans “in their language” (the plural is added in by the translator), because “the language” they all were speaking was actually Mongolian, the lingua franca of the Khalkha-Zunghar rule.

Greg Pringle:

I cannot comment one way or another on the Muslims and Tibetans, but I have read (I don't remember the source) that when the Torghuts (Kalmyks) fled Russia and returned to China in about 1771, the head of the Torghuts personally met and spoke with Qianlong, and Mongolian was the language used in the meeting. Despite the difference in dialects (Torghuts spoke a far western variety while Qianlong spoke the language of the eastern Mongols, who were part of the Manchu banners), they were apparently able to make each other understood without interpreters.

Johan Elverskog:

That statement is much bandied about, and while it is likely Qianlong could converse with Tibetans and Mongols, it seems unlikely he could speak any Turkic language (much less Persian or Arabic).

Gray Tuttle:

I don't know how much he was able to speak Tibetan, but he did try, and bragged about it at the time (in Empire of Emptiness, right at the end, Pat Berger translates a passage to the same effect re: Qianlong bragging about communicating directly with the Panchen Lama around the same time this quote is from.

Peter Perdue:

I don't believe Qianlong for a second: he was one of the most boastful and vain of all emperors, but his Manchu was much worse than Kangxi's, not to mention Tibetan and Mongolian. Maybe he knew the equivalent of 你好吗 and that was enough.

Mark Swofford:

The Wikipedia article on the Qianlong emperor cites Mark Elliott of Harvard's book Emperor Qianlong: Son of Heaven, Man of the World. for the unquoted statement "In his childhood, the Qianlong Emperor was tutored in Manchu, Chinese and Mongolian,[41]" and the unreferenced assertion that he "arranged to be tutored in Tibetan, and spoke Chagatai (Turki or Modern Uyghur)."

Peter Golden:

There seems to be some truth in this. According to the lengthy Wikipedia entry on him, he is reputed to have spoken Manchu, Chinese, Mongolian, Tibetan and Chaghatai (that would be the “Muslim” language).

Mårten Söderblom Saarela:

I know he studied various languages, but not sure how well. I recall seeing Tibetan-language flash cards that he used at the palace museum library in Beijing in 2013. At that time, the librarian, 春花, told me that he studied for his meeting with the Panchen Lama, but during the meeting the two of them actually spoke in Mongolian. Qianlong evidently knew Mongolian, and also spoke it during audiences with Dzunghar visitors.

Mark Elliott:

It’s credible that Qianlong wrote this, yes. In fact, I think I remember seeing it somewhere before.

Is it credible that the claim is true? He would have been able to have had a limited conversation, I think, with Mongol visitors, but I don’t think he would have managed more than a few phrases in Tibetan (his friend the Janggiya khutukhtu may have taught him some). No chance he could have a conversation in Turki/Uyghur, I don’t think.

Note however that the claim is, “以其語慰問,” which I would translate not as “use their languages” but as “greet them in their own language.” This he could certainly have pulled off. So I think the real issue here is with the English translation.

Steve Wadley:

My Manchu reading group companions were much more adept at finding the quote. It is in a preface to a poem about pacifying Taiwan of all places and it is quoting the commentary on the poem, so not something the Qianlong Emperor himself said so the British Museum has misapplied the attribution by translating it in first person. As you see the commentary says he studied those various languages when he conquered the people, but their opinion was that perhaps he may have studied enough to be able to greet the various groups in their own language but may not have known much more than a few phrases of greeting. Here's the reference, the commentary is in green type:

序欽定平定台灣紀略 清 乾隆五十三年廷臣 奉敕撰

(174)

及時膏澤可教屯,光武寧當學閉門。弗藉舌人通譯語乾隆八年始習蒙古語;二十五年平回部,遂習回語;四十一年平兩金川,略習番語;四十五年因班禪來謁,兼習唐古忒語。是以每歲年班,蒙古、回部、番部等到京,接見即以其語慰問,無藉通譯。元夕,命新舊諸番入同樂園,隨觀燈火,並燕笑聯情,用示柔遠之意,華鐙聯席共歡論。

(source)

VHM: I leave the Chinese text intact for Sinologists, Manchuists, and other relevant specialists who need access to it.

Perhaps the Manchu rulers' mastery of many languages of their subjects was one of the reasons for their personal longevity (two of them, including Qianlong, ruled for 60 years or more; all 11 of them ruled for an average of 25 years each) and the longevity of their dynasty (1636-1911, for a total of 275 years).

Selected readings

- "Manchu 'princess' speaking English" (8/23/20)

- "Mandarin and Manchu semen" (3/11/22)

- "Sino-Manchu seals of the Xicom Emperor" (2/12/20)

- "Manchu illiteracy" (4/14/16)

- “Ornamental Manchu: the lengths to which a forger will go” (4/24/21)

- "Faux Manchu: Ornamental Manchu II" (6/23/21)

- "Sibe: a living Manchu language" (9/30/17)

- "Sibe and the revival of Manchu" (10/4/21)

- "A rebirth for Manchu?" (1/16/16)

- "Manchu film" (12/31/16)

- "Manchu loans in northeast Mandarin" (10/17/13)

[N.B. I wish to thank Kiewwoo Goh for spotting this quotation in the British Museum and for being intelligently curious enough about it to send it to me for further consideration. Thanks also to Josh Fogel for responding to my inititial query on the quote. Above all, I want to thank all readers and collaborators of Language Log for contributing to a great, cooperative enterprise that makes possible such marvelous solutions to compelling questions as the one embodied in this post. Zhōngxīn gǎnxiè 衷心感謝 ("With heartfelt thanks!")]

Victor Mair said,

April 7, 2023 @ 6:34 am

From Kiewwoo Goh:

Is the character ‘’禦‘’ of "禦制詩‘’ an issue at all?

Victor Mair said,

April 7, 2023 @ 6:35 am

From Lucas Christopolous:

I remember temples of the Qing dynasty in Beijing (I think the Yonghe gong 雍和宫 or the Summer Palace) with stone inscriptions translated in these languages together with Chinese. Very plausible that the emperor was aware and curious about was what written in his buildings.

J.W. Brewer said,

April 7, 2023 @ 7:39 am

The specific set of five ethnicities the emperor could allegedly speak to (or "greet" or what have you) caused me to learn that something like the https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Five_Races_Under_One_Union concept was already floating around in political rhetoric in that part of the world for centuries before its use in the early days of the ROC.

Victor Mair said,

April 7, 2023 @ 8:36 am

Excellent observation, J. W. Brewer!

See also:

"The languages on Chinese banknotes" (9/16/13)

An interesting phenomenon across Eurasia in which the Mongol Empire played an important role. See Tom Allsen's chapter in The King's Dictionary. The Rasûlid Hexaglot: Fourteenth Century Vocabularies in Arabic, Persian, Turkic , Greek, Armenian and Mongol, ed. P.B. Golden (Leiden: Brill 2000).

The Manchus appear to have picked this up from the Mongols. I wonder whether the Mongols originated it or whether it goes back even earlier.

Pamela Crossley said,

April 7, 2023 @ 8:37 am

greatly enjoying these comments. these words were certainly written by Hongli, but as Peter points out that doesn't mean there is anything true about it. i believe he had a very good knowledge of Mongolian and it could have been better than that. he spent (or appeared to spend) a good deal of time correcting Mongolian petitions and reports, and insisting they be rewritten (as with anything imperial, did he do this in his own body, or through his extended amanuenses? interesting to know but not necessarily important); he wrote repeatedly that Mongolian and Manchu were sibling languages, which could mean he complacently assumed that his Manchu made him good at Mongolian, but i think the evidence is sufficient that he was competent in Mongolian. he had to know quite a bit of Tibetan for cult practices, and was buried with Tibetan dharani all over his shroud, so he must have had some kind of familiarity with it. as for Uyghur, i think his knowledge of it was purely symbolic. but i do think it is possible he knew a word or two of english, if that helps. overall i think there is a theme here that the simultaneity of the emperorship did not mean the person of the present emperor was fluent in all the imperial languages, which i think is a sound principle.

Kingfisher said,

April 7, 2023 @ 11:01 am

There's such a store of languages to which I've put my mind

The gate to learning opens once the conquests are behind

No need to borrow others' tongues to make my words be known

'Midst handsome lamps and cozy mats, the chatting's all our own

(Qianlong had already begun learning the Mongol language at the age of seven. At twenty-four, after having pacified the Hui groups, he practiced the Hui language; at forty, after having pacified the two Jinchuan regions, he made a rough study of the Fan language; and at forty-four, upon the occasion of the Panchen Lama coming to the capital to pay his respects, he studied the Tibetan language as well. Thus each year when the Tibetans, Mongols, people from the Hui or Fan groups, or other peoples would come to the capital, upon meeting with them Qianlong would promptly ask after them in their own languages, without resorting to translation. And on the first evening of the new year, he would order all these subject peoples, whether of newer or older subjugation, to go into the pleasure gardens together to view the lanterns and to share their feelings through conversation and laughter, as a means of demonstrating his power to subdue such distant places.)

J.W. Brewer said,

April 7, 2023 @ 11:35 am

My earlier comment should have said "caused to re-learn" rather than "caused to learn," since I apparently had failed to retain all of that interesting information from the 2013 comment thread that I read and participated in at the time …

David Marjanović said,

April 7, 2023 @ 3:23 pm

Well, compared to anything Sinitic, they look very similar indeed…

Victor Mair said,

April 8, 2023 @ 7:12 am

From Alan Kennedy:

Someone mentioned Empire of Emptiness by Patricia Berger (University of Hawai'i Press, Honolulu 2003), and judging from the index, Berger has done an in-depth study of this subject, with numerous page references to "multilingualism," "language," "languages" and "inscriptions."

On page 38, she quotes the Qianlong emperor:

"In 1743 I first practiced Mongolian. In 1760 after I pacified the Muslims, I acquainted myself with Uighur. In 1776 after two pacifications of Jinchuan I became roughly conversant in Tibetan . . . "

Victor Mair said,

April 9, 2023 @ 8:59 pm

From Bettine Birge:

I think Qianlong did likely speak a number of languages, so this is plausible. But the Chinese text has "deng 等" in there, which makes it seem like an exaggeration. And what language did the Hui 回("Muslims") presumably speak? That term can be used very broadly.

Bathrobe said,

April 10, 2023 @ 4:32 pm

It won't affect the meaning, but the punctuation has been modernised in that short passage. I don't think ,、and 。were used in Qianlong's time.

Victor Mair said,

April 12, 2023 @ 10:26 am

From Arina Mikhalevskaya:

I don't trust Qianlong either! However, I think he may have known some words and phrases from those languages.

A few studies mention Qianlong's multilingualism (e.g., one by Zhang Xiaoli). Their information mainly comes from Qianlong's three poems and his self-commentaries to those poems.

The museum exhibit caption is based on Qianlong's 1788 poem "Shangyuan deng ci you xu 上元燈詞有序":

In another poem, Gu xi 古稀, written seven years earlier in 1781, Qianlong mentioned that he did rely, to some extent, on the help of interpreters in what concerned Mongolian, Uighur, Tibetan, and Tangut:

Patricia Berger offers a helpful way of understanding Qianlong's claim to know many languages as "facile multilingualism," suggesting that it may have been akin to that of Pope John Paul II, famous for his annual Christmas greetings in fifty or more languages and his ability to address any crowd in their native tongue (Empire of Emptiness, p. 38).

During formal audiences, Qianlong possibly would not need to speak much.

That said, in 1779, Qianlong mentioned he personally corrected translations of edicts into Mongolian issued by Lifanyuan because they were unreliable, which does suggest a working-level knowledge of Mongolian.

chris said,

April 17, 2023 @ 5:17 pm

I doubt if very many people were going to tell the Qianlong Emperor that he wasn't doing well at speaking their language, even if it was true. It may have been hard for him to get an accurate assessment of his own ability.

Or, of course, an emperor can brag as easily as anyone (easier, really, because so many people fear to contradict him).

Victor Mair said,

April 25, 2023 @ 4:12 pm

For one indication of the deep involvement of the Manchu court centering upon the Qianlong emperor with Tibetan Buddhism, see:

Françoise Wang-Toutain, with the participation of Francesca de Domenico,

Le décor de la tombe de Qianlong (r. 1735-1796): un empereur mandchou et le bouddhisme tibétain, 2 vols. (2017).