Capitals and upper case letters

« previous post | next post »

I am a fan of capital letters. They let us know when a noun is a proper noun — the name of a person, a place. But I also have to admit that they are something of a bane at times. For example, I grew up learning that one should capitalize all terms in a title except for prepositions, words of three letters or less, definite and indefinite articles, and so forth. For many publications, however, including here at Language Log, it seems to be house style not to capitalize all the terms of a title over three words in length, unless they are proper nouns.

This indefiniteness about whether or not to use capitals in titles gives me lots of headaches. Because I'm a stickler for bibliographical exactitude, when I'm preparing my list of references and footnotes, it causes me much grief to decide whether to include capitals or not when different sources threat them dissimilarly.

Now, in "The Curse of Capitals and the Theology of Punctuation", Patheos / Anxious Bench (4/28/22), Philip Jenkins says:

I have invented a new discipline, the Theology of Punctuation.

Some years ago, I published a book called Crucible of Faith: The Ancient Revolution That Made Our Modern Religious World, about the couple of centuries preceding Jesus’s time. One of the persistent problems I have relates to capitals and upper case letters. That may sound trivial, but it actually gets to some quite critical issues of translation and interpretation.

Let me take one famous quotation from the Gospels, concerning the birth of Christ. This is from Luke 2 (NIV), and I invite you to look at the punctuation, and the use of upper case letters:

But the angel said to them, “Do not be afraid. I bring you good news that will cause great joy for all the people. Today in the town of David a Savior has been born to you; he is the Messiah, the Lord. This will be a sign to you: You will find a baby wrapped in cloths and lying in a manger.”

Nothing seems unusual or improper in that, and it seems natural and indeed essential to use capitals for a word like Savior. When we use capitals, we are making a clear statement about the words that we so dignify. We are stressing that those words represent something special, perhaps THE example of its kind, rather than any generic example. Jesus is to be a Savior, rather than just someone who saves something unspecified. In religion, we mean something totally different if we refer to Virgin rather than virgin, or if we refer to the Father and the Son, rather than the father and the son. To write of God is usually to refer to the one absolute and transcendent Creator (see, I capitalized that – did you notice?) while a god is a more commonplace thing. Often, our editorial decisions carry quite unintentional theological weight.

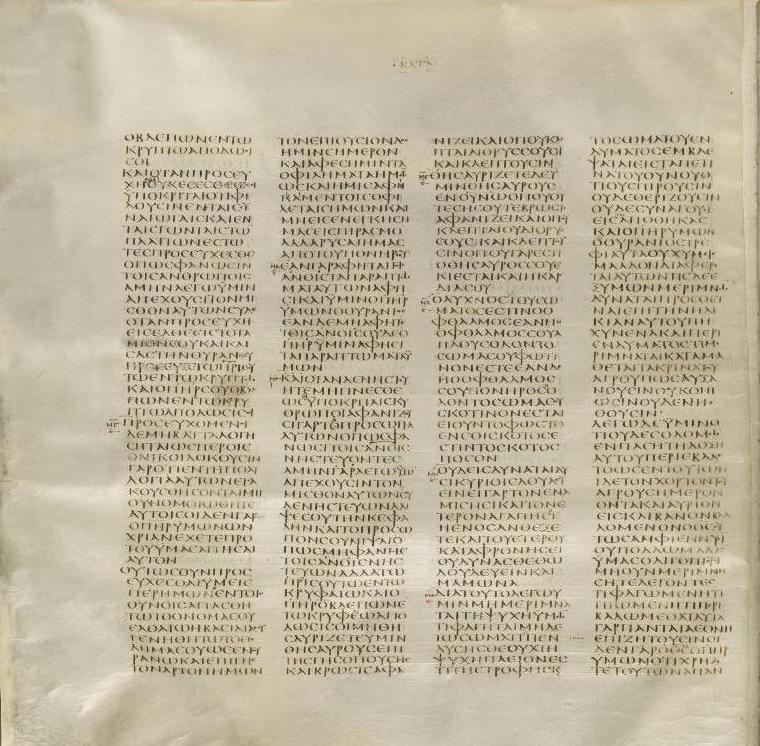

But here is the problem. Virtually all such decisions are arbitrary, and rely on editorial tradition. When we translate the New Testament, we have no capitals or upper/lower case differences to guide us. Very early Greek New Testament manuscripts are entirely in what we would call capitals or upper case. Hence, there is no distinction between upper and lower case, and thus (in our sense) no word is dignified or distinguished by a capital.

Matthew 6 in Codex Sinaiticus (Public Domain image)

- "Capitalization" (5/27/18)

- "Assortative peeving" (12/29/14)

- "New infrastructure at Language Log Plaza" (4/8/08)

- "Lower Case Names?" (1/18/05) — including the case of e.e. cummings (should there be a space between the two "e's" [how do we deal with the double and single quotation marks here?] and should there be periods after each of the two "e's"? Does the Chicago Manual have clear answers to all such questions? Or should we just learn to live with a little bit of slippage, flexibility, and autonomy? This post begins with e.e. cummings and ends with an Egyptian seal, the first three characters of which spell the name Amon, the second row reads /twtʕnx/, hence Tutankhamen, but I can't spot a capital letter among those hieroglyphs.

- "…'such matters as Opinion, not real worth, gives a value to'" (11/20/16)

- "Aggressive periods and the popularity of linguistic" (11/26/13)

- "Should I capitalize 'l' if I put log2 at beginning of a sentence?" (4/30/18)

- "When should the word "English" be capitalized?" (8/10/10)

- "Uppercase and lowercase letters in Cantonese Romanization" (5/28/20)

- "Loose Romanization for Cantonese" (9/21/19)

- "The Roman Alphabet in Cantonese" (3/23/11)

- "Ask Language Log: The alphabet in China" (11/6/19)

- Mark Hansell, "The Sino-Alphabet: The Assimilation of Roman Letters into the Chinese Writing System," Sino-Platonic Papers, 45 (May, 1994), 1-28 (pdf)

- Helena Riha, "Lettered Words in Chinese: Roman Letters as Morpheme-syllables" (pdf)

- "Zhao C: a Man Who Lost His Name" (2/27/09)

- "Creeping Romanization in Chinese, part 3" (11/25/18)

- "The actuality of emerging digraphia" (3/10/19)

- "Sememic spelling" (3/27/19)

- "Polyscriptal Taiwanese" (7/24/10)

- "Love those letters" (11/3/18)

- "Acronyms in China" (11/2/19)

[Thanks to Barbara Phillips Long, from Shiremanstown, Pa. — nice place name, eh?]

Scott P. said,

May 1, 2022 @ 7:33 pm

Even the existence of something called "Luke 2" is an arbitrary editorial choice!

mg said,

May 1, 2022 @ 7:44 pm

No capitals in Hebrew, either.

Laura Morland said,

May 1, 2022 @ 8:28 pm

"For many publications, however, including here at Language Log, it seems to be house style not to capitalize all the terms of a title over three words in length."

Hmmm… you're one of the two pillars of LL; can't you change it back to the Good Old Ways?

P.S. French never picked up the habit of capitalizing words in titles, except for proper names.

Dick Margulis said,

May 1, 2022 @ 8:53 pm

As for references, take advantage of a reference manager (Zotero, Endnote, or the like). Enter the data once and let the software spit out references in whatever format the journal prefers.

But regarding letterforms, majuscules and miniscules (in the Latin alphabet) have been with us for quite some time, but uppercase and lowercase have only been around since the latter part of the fifteenth century. Before Western printing was done with moveable type, there was no need for cases to sort it into.

julie lee said,

May 1, 2022 @ 8:55 pm

"This indefiniteness about whether or not to use capitals in titles gives me lots of headaches."

This made me want to cry. I've had those headaches.

"The Curse of Quotation Marks"

This made me laugh. I know the curse.

I see the post has "Sinographic". Then it should be Sinology, like

Egyptology. But the Cambridge English Dictionary has "sinology" and "sinicize". Also "anglicize" but "Americanize".

Thanks, Professor Mair. I love this post.

Mehmet Oguz Derin said,

May 1, 2022 @ 9:06 pm

Old Turkic script also does not have a notion of capitals; also, I did not notice any particular attention to word separator when it comes to fictional or actual entities of importance.

Greg Ralph said,

May 1, 2022 @ 9:20 pm

On the use of capitals in South Asian-derived scripts, Javanese has "aksara gedhe" (Large Letters) which are used to signify respect or importance in much the same way that capitals are. It's been a long time since I studied Javanese, but I seem to recall that the aksara gedhe derived from letters for aspirated consonants which weren't required in Modern Javanese (although were used in Old Javanese because of the significant Sanskrit vocabulary).

Barbara Phillips Long said,

May 1, 2022 @ 10:21 pm

@ Dick Margulis —

Beyond majuscule and minuscule and upper and lower case there are “small capitals” and “petite capitals”:

Research by Margaret M. Smith concluded that the use of small caps was probably popularised by Johann Froben in the early 16th century, who used them extensively from 1516.[1] Froben may have been influenced by Aldus Manutius, who used very small capitals with printing Greek and at the start of lines of italic, copying a style common in manuscripts at the time, and sometimes used these capitals to set headings in his printing; as a result these headings were in all caps, but in capitals from a smaller font than the body text type.[1] The idea caught on in France, where small capitals were used by Simon de Colines, Robert Estienne and Claude Garamond.[1][8][9] Johannes Philippus de Lignamine used small caps in the 1470s, but apparently was not copied at the time.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Small_caps

Michèle Sharik Pituley said,

May 1, 2022 @ 10:47 pm

I would love to know more about The Curse of Quotation Marks!

Andrew Usher said,

May 1, 2022 @ 10:48 pm

Letter case (or whatever you want to call it) is a part of English and has been so since before printing. Errors in capitalisation are no different than errors in spelling. The fact that lowercase 'christ' is flagged by spell-checkers in not 'theological correctness' but a reflection of actual English use – 'Christ' is always so written even when not referring to Jesus, while 'Messiah/messiah' isn't always.

So the use of capitals in a translations is not fundamentally different from other issues in translation; there is no translation without some interpretation, and in the case of the Bible the original intent is quite often unclear. In such cases an unbiased translator simply has to decide what is most likely.

k_over_hbarc at yahoo.com

~flow said,

May 2, 2022 @ 1:08 am

I can recommend the relevant Wikipedia article on the topic: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Letter_case#Bicameral_script

To quote: "[Bicameral scripts include:] Latin, Cyrillic, Greek, Coptic, Armenian, Adlam, Warang Citi, Cherokee, Garay, Zaghawa, and Osage", from which we can safely say that multicameral scripts are rare in the world, and Japanese orthography with its two, three or four 'cases' is somewhat of an outlier.

Philip Taylor said,

May 2, 2022 @ 1:32 am

"one should capitalize all terms in a title except for prepositions, words of three letters or less, definite and indefinite articles, and so forth" — it is surely the "and so forth" that is the real problem. Consider "Professor Burns Leaves on Commencement Day", taken from the thread entitled "Today's Crash Blossom". If Professor Burns is a person, then I would title-case the headline as "Professor Burns leaves on Commencement Day"; if instead an unnamed professor set fire to a pile of leaves, then I would title-case it as ""Professor burns leaves on Commencement Day". Both "Burns/burns" and "Leaves/leaves" are "so forths", and therefore ill-defined, but intelligent title-casing can eliminate the ambiguity that can arise from the unthinking application of an under-specified rule.

~flow said,

May 2, 2022 @ 1:38 am

As regards the question why we have case in Latin (and Cyrillic, Greek, Coptic, and Armenian) at all—that seems to be related to the development of lettering in manuscripts over the first ten or so centuries CE. As an example, when you take a look at the snippet from a 10th c Vulgate Luke presented at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carolingian_minuscule, you will realize that while the body of the text is written in what we now call Carolingian minuscule—a style of writing that was brought about by continued reproduction and innovation over the centuries, then to be standardized in the time of Charlemagne—some portions of the text use a style of lettering that is much closer to the capital letters of the Trajan column. This was done rather systematically in manuscripts and there was a wide range of styles—'fonts' if you will—at the disposal of the scribes who used it in a somewhat predictable manner (e.g. you would not expect the two styles employed in the that Vulgate manuscript to swap roles).

This goes to show that although we inherit the most common names for majuscules and minuscules—upper and lower case—to the advent of printing in the late 15th c, the matter of fact is rather considerably older and richer. There are alternative, plausible timelines where the Latin script remains monocameral or turns out to be tri- or quadricameral; the latter is (somewhat) what actually did happen for a sizable portion of European history when Black letter was still used in book printing, advertisement, personal writing and newspapers *alongside* with Roman / round / Antiqua letters. In fact, even after the war there were documents and books printed that made judicious use of "Antiqua und Fraktur", both in two cases.

The one person that we have to thank for destroying this typographic tradition along with so uncounted lives, cities, and huge swaths of a living and rich cultural heritage shall remain unnamed here, for fear that the wheels of the juggernaut have come around once more to feast on our flesh and blood.

Philip Taylor said,

May 2, 2022 @ 2:33 am

"The one person that we have to thank for destroying this typographic tradition …" — I am intrigued, ~flow. I have been using computer typesetting since before the advent of the Linotronic 300 (1984) and cannot identify the person to whom you refer. I understand your fear of his/her wrath, but if you could provide even a clue as to his/her identity, I would be forever in your debt.

~flow said,

May 2, 2022 @ 2:34 am

1942

Philip Taylor said,

May 2, 2022 @ 2:55 am

Well, I am forced to guess (as you perhaps intended), so I must ask : does the following refer to the event(s) to which you refer ?

Tom said,

May 2, 2022 @ 5:23 am

Protestant Bibles include a space before the word 神shén 'God.' (Apparently this is because the same publisher of an early Chinese Bible produced two versions of the bible: one where the word is translated 神shén and another where it is translated 上帝shàngdì. So as to not typeset the whole bible twice, two spaces were provided each time, and the appropriate characters could be inserted for each version. This meant that 神shén had a blank space before it.)

Regardless of the history, most people I know interpret this leading space as a sign of respect/uniqueness, quite analogous to the capitals that show up in english Bibles.

Another case is pronouns. In English, Bibles will sometimes capitalize pronouns referring to God, as a form of respect. Similarly in Chinese, it is not uncommon to see the pronoun 他tā written as 祂, with a cultic radical in place of the human radical.

~flow said,

May 2, 2022 @ 5:27 am

now you did name what should not have been named

Philip Taylor said,

May 2, 2022 @ 7:02 am

Well, in 1973 it was reported :

but I cannot trace any later publications suggesting that he may still be alive, so your fears "that the wheels of the juggernaut [will] come around once more to feast on our flesh and blood" may, while understandable, be unfounded.

Andrew Usher said,

May 2, 2022 @ 7:54 am

I think that can surely be put to rest – historical mention of the Nazis is not out of line here. To the point, the argument 'Hitler and the Nazis were bad and therefore everything they did was bad' if of course invalid, and I can't see that bringing Germany into typographic alignment with the rest of Europe – which had already completely dropped Fraktur/blackletter – was a bad thing. Perhaps you could give an example of the use of both the two typefaces being an actual advantage?

KeithB said,

May 2, 2022 @ 8:10 am

This is also an issue at the crucifixion when the centurion says something like "Surely, this was the Son of God" or "Surely, this was a son of the gods".

And does anyone know what rules Trump uses for capitalization?

Philip Taylor said,

May 2, 2022 @ 8:19 am

If the centurion had believed in multiple deities, would he not have said "a son of the Gods" ? (Assuming, of course, that one can capitalise anything in one's speech …).

Dan Curtin said,

May 2, 2022 @ 8:34 am

Of course, we could just follow the Greek ms all the way: "YOUARETHECHRIST."

THISWOULDSAVEALOTOFTROUBLEWITHSHIFTINGPUNCTUATIONANDOTHERCONVENTIONS.

PS. It is hard to type without hitting the spacebar!

KeithB said,

May 2, 2022 @ 8:48 am

Dan Curtin:

While you included the period, it would also end the argument as to whether you should have one or two spaces after the period.

Antonio L. Banderas said,

May 2, 2022 @ 9:09 am

Jesus’s

How do you pronounce this one?

According to the Longman Pronunciation Dictionary, among others, it should be

Jesus’ ˈdʒiːzəs

Philip Taylor said,

May 2, 2022 @ 9:39 am

My reading of the (electronic) LPD suggests to me not that "Jesus's" should be pronounced /ˈdʒiːz əs/ but rather than "Jesus's" should be spelled Jesus’ and pronounced /ˈdʒiːz əs ǁ -əz/. I'll consult my hardback copy shortly and report back if it differs from the electronic version.

Robert Coren said,

May 2, 2022 @ 9:52 am

I don't know a whole lot about typographical history, but I would be inclined to suspect that much of the capitalization that we take for granted in the Bible is the result of capitalization conventions in early 17-century English (i.e., King James version), and such conventions have changed a lot (and been more strictly codified) since then.

J.W. Brewer said,

May 2, 2022 @ 11:38 am

@Robert Coren: Quite a lot of modern English Bible translations have different capitalization conventions than the KJV. For example, the voice from heaven in Matthew 3:17 says (in KJV) "This is my beloved son" but the "my" is done as "My" in many but certainly not all recent versions. But that's the *current* KJV whose orthography, including capitalization decisions, was finally frozen circa 1762 – the original 1611 edition had "This is my beloued Sonne."

The Mark 15:39 version of the centurion's statement referenced by KeithB comes out in the online Greek NT I most commonly use myself as "Ἀληθῶς ὁ ἄνθρωπος οὗτος υἱὸς ἦν Θεοῦ,"* i.e. the sentence-initial word and the word for "God" are the only ones capitalized. But there is apparently more than one capitalization style currently extant in printed/digitized versions of the Greek NT because I can easily google up another version that capitalizes the word for "S/son." And as noted above all of these modern printed/digitized editions deviate from the style of the earliest manuscripts. S/son does seem to get capitalized in at least many modern editions of the Latin Vulgate ("Vere hic homo Filius Dei erat"), but I wouldn't be surprised to learn that that is a convention that is substantially more recent than St. Jerome.

*There is apparently manuscript variation as to whether οὗτος precedes or follows ὁ ἄνθρωπος and different editions naturally have different views as to which is the better reading, but I don't think that this variation in Greek word order is particularly relevant to the best English translation, much less to English capitalization conventions.

J.W. Brewer said,

May 2, 2022 @ 12:17 pm

Jenkins' separate piece on "The Curse of Quotation Marks" is interesting because it reveals a(nother) self-created problem of modern times. The King James Version has no quotation marks at all, including in places where the relevant third-party narrator appears to be passing on a verbatim* quote from a specified "character." The examples Jenkins gives from some more recent translations suggest that once you start using quotation marks (including in his examples as "scare" or "sneer" quotes) you then need to take contentious interpretative positions on many Biblical passages where the presence or non-presence of quotation marks might give the passage a different nuance and not everyone agrees on what the proper nuance is.

*I think some folks will indeed argue that the very idea of a sharp/clear distinction between a verbatim quotation and a fair paraphrase of the gist of what someone said is largely a modern one that would not have seemed particularly significant to most people in the Mediterranean world 2000 years ago, but that's a separate but related issue.

Coby Lubliner said,

May 2, 2022 @ 1:34 pm

The simultaneous use of fraktur and antiqua, the former for German (and possibly Scandinavian) words and the latter for "foreign" ones, was standard in German typography until the 19th century, and could sometimes convey some subtle distinctions. In the first press notice about Franz Liszt, in a German newspaper published in Bratislava/Pressburg, his name is printed in Fraktur, on the assumption that he was an ethnic German (while that of his host, the Hungarian Count Eszterházy, is in antiqua). Since his father, however, was eager to promote Franz as a Hungarian, the announcement he posted in a Vienna newspaper a couple of years later had 'Liszt' in antiqua.

Michael said,

May 2, 2022 @ 5:33 pm

Interestingly, the word "Our" in the title of your book has been capitalized, although it is a word of three letters or less. I believe that this is traditionally correct, and that the rule here is somewhat more complicated – similarly, I find a book titled "To Be or Not to Be: That Is the Adventure," which seems to go all over the place with the "3-letter rule," if such does exist. Part of speech (preposition, conjunction, article) seems to be more determinative than length.

David C. said,

May 2, 2022 @ 6:59 pm

@Tom

The use of a space before the word 神 ("God") is the application of Nuótái 挪抬 from traditional Chinese writing, used in a range of circumstances to denote respect. It was adapted to the translation of the Bible partly to distinguish upper-case God from lower case god (false gods).

The Wikipedia page on the subject contains a good explanation:

https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%8A%AC%E9%A0%AD

Tom said,

May 2, 2022 @ 10:57 pm

@David C.

Good to know the name for this. The story about the typesetting has been passed around and I have never seen a solid source for it.

But what gives it a tinge of credibility is that only 神 is treated this way in bibles, and not other concepts that might be distinguished (灵、儿子、主等).

Victor Mair said,

May 2, 2022 @ 11:06 pm

Although Michèle Sharik Pituley would like to hear about "The Curse of Quotation Marks", I'll pass on it for now, since J.W. Brewer has already addressed it in his second comment above, though I may come back to it later if the occasion should arise.

~flow said,

May 3, 2022 @ 2:13 am

@Andrew Usher "I think that can surely be put to rest – historical mention of the Nazis is not out of line here. To the point, the argument 'Hitler and the Nazis were bad and therefore everything they did was bad' if of course invalid, and I can't see that bringing Germany into typographic alignment with the rest of Europe – which had already completely dropped Fraktur/blackletter – was a bad thing."

This answer still drives me mad so I have to restrain myself. Let us say I don't need no stinkin' fascist to "bring me in line with" anyone typographically. BTW your argument is a surefire way to get yelled at at any reasonable German kaffeeklatsch; we call it the Autobahnargument ("not everything was bad, you see, just think of the autobahns").

Jonathan Smith said,

May 3, 2022 @ 7:40 am

happened in China —

Teacher: How's it coming with the alphabet

Struggling student of English: …OK I guess (…还行吧)

Teacher: OK let's hear it

Student: …capitals or lower case? (…大写还是小写?)

Chas Belov said,

May 3, 2022 @ 10:23 am

Coincidentally, I took a class on writing for the web yesterday where they suggested sentence case because it is marginally faster to read.

And there's the matter that words are usually read the same by screen reader software regardless of whether they are capitalized or not, although words in all caps may be spelled out by some software, whether always or when not recognized as a word in the language of the text.

Philip Taylor said,

May 3, 2022 @ 1:54 pm

Jonathan's "capitals or lower case? (…大写还是小写?)" somehow makes sense to me. My parents taught me the alphabet, long before I started school, as /eɪ, biː, si, …/ and I felt absolutely humiliated when my first primary school teacher tried to persade me to pronounce the letters using the "phonics" system (/æ, bə, sə, …/). To avoid conflict, I went along with /æ, bə, sə, …/ for the lower-case letters but no power on earth could persuade me to do the same for the capitals.

Victor Mair said,

May 4, 2022 @ 7:07 am

From Bruce Brooks:

Victor Mair has brought to my attention a writing by one Philip Jenkins. Jenkins outlines a perfectly sound rationale for capital as opposed to small letters: the former are for specific reference or emphasis. So far so good. Then, noting that this contrast is not observed in the Greek of Codex Sinaiticus (I checked my personal facsimile copy, and sure enough, that is correct), he goes on to say, "Virtually all such decisions are arbitrary."

No, they aren't, they are highly functional and intelligible. They are to be explained by the march of civilization.

There is a profound difference between a writing that is used as a mnemonic, a writing of a text that the reader already possesses, and a writing that serves to convey new information, for the reader of a modern mystery novel. In the latter case, the reader is not equipped to fill in what the script does not provide. The catch is that all ancient writings are mnemonic texts. It is the same with vowel pointing of Hebrew. When you already know what word is intended, because you have been reciting that text since childhood, just the consonantal outline of th wrd suffices. Otherwise, it does not. As writings began to be more widely used by those who did not already possess the text in question, confusion resulted, and the script accordingly differentiated itself enough to avoid errors by that new readership.

Lack of word spacing was efficient; it saved parchment, and parchment was expensive. For that time, it was the maximally efficient solution. It later led to confusion, and some recent scholars have made their reputations by successfully decoding a text in scripta continua which had been wrongly divided by previous scholars. Thus ,

http://www.wsproject.org/method/philology/gallery/madvig.html

And there is worse to tell of capitalization. The French are fond of decapitalizing everything, don’t ask me why; maybe it saved ink. Also unclear is why American library cataloguers should have picked up that eccentricity; perhaps it relieved them of thinking. At any rate, though myself an American library cataloguer, I hereby pronounce a curse on the others of that tribe. If they do not repent within a suitable time, I will not be responsible for their place in the hereafter.

(European publishers have gotten in the habit of printing titles of scholarly books all in caps, which leaves the key decisions to their readers, or their readers’ cataloguers. Chickening out).

As for the theologians, let them come under the same curse, unless they see their way clear to capitalizing “Biblical,” as the proper adjective corresponding to “Bible” (compare China / Chinese, or Hungary / Hungarian). I consider this fair warning. Let those who feel I have omitted someone known to them pass it on to that acquaintance.

So Jenkins was doing fine, he just should have quit while he was ahead.

Then there is Cummings. Note that he never spelled his own name in lower case. Check it out.

J.W. Brewer said,

May 4, 2022 @ 9:27 am

I wonder if Bruce Brooks and Philip Jenkins are talking past each other. Pointing out that capitalization conventions are "arbitrary" does not necessarily mean that they're useless. Given that the details of capitalization conventions vary considerably between English and other languages (including other languages with fairly similar associated cultures), have varied somewhat within English over time, and indeed exhibit some degree of synchronic variation within English today (as confirmed by dueling stylebooks) it is obvious that the details of the conventions are indeed arbitrary and contingent at the margin. Either there are multiple rival approaches that are all functionally "good enough" compared to the days before mixed-case writing was developed to survive and thrive, or, put another way, even if there is some theoretically perfect/optimal way to do it, the evolutionary pressures are not strong enough to make all languages (or rather, all languages with scripts that permit mixed-case writing) converge on it rather than remain "stuck" with a suboptimal-but-adequate system.

Antonio L. Banderas said,

May 4, 2022 @ 11:12 am

@Philip

What phonics is that?

B, or b, is the second letter of the Latin-script alphabet. Its name in English is bee (< Latin bē (Middle English /beː/)).

Philip Taylor said,

May 4, 2022 @ 11:33 am

Antonio — Synthetic phonics, as defined by the UK National Literacy Trust :

Antonio L. Banderas said,

May 4, 2022 @ 12:18 pm

@Philip

So what is the purpose of the sequence bə, sə, (ətʃ?, əks?) etc. exactly?

Does o read ɒ/ɔː ?

What goes for u? ʊ? Maybe ʌ?

Philip Taylor said,

May 4, 2022 @ 1:11 pm

Please bear in mind that not only did I feel humiliated having to "spell out" a, b, c … as /æ, bə, sə, …/, I continue to believe to this day that synthetic phonics has a place only in remedial situations and is unnecessary for the averagely-abled child. So any explanation that I try to give may not accord with what the teachers of synthetic phonics would seek to convey. That said, I would answer your questions as follows :

"what is the purpose of the sequence bə, sə, (ətʃ?, əks?) etc. exactly?"

Not sure about (ətʃ?, əks?), as they don't look very similar to what I was taught, but the purpose of /æ, bə, sə, də, ɛ, fə, gə, hə, ɪ, dʒə, kə, lə, mə, nə, ɒ, pə, kwə, rə, sə, tə, ʌ, və, wə, ksə, jə, zə/ (I hope I have remembered these correctly, having not needed them for some 70 years) is to convey the most common sound associated with each of the 26 letters of the English alphabet.

"Does o read ɒ/ɔː ?" — I transcribed it as /ɒ/, using the LPD as my guide (the vowel in "job")

"What goes for u? ʊ? Maybe ʌ?" — yes, /ʌ/.

Terpomo said,

May 4, 2022 @ 1:35 pm

As a child I had a book with stories from the religions and mythologies of the world which used capitalized pronouns for deities of all religions. It seems to me that this is the correct approach for a publication with no explicit religious affiliation- capitalized pronouns for either all deities or none, not some-and-not-others.

Philip Taylor said,

May 4, 2022 @ 1:38 pm

Huh — I now realise that I did not remember correctly; the synthetic phonics sequence starts /æ, bə, kə/, not /æ, bə, sə/. Perhaps I should have paid more attention !

Peter Grubtal said,

May 5, 2022 @ 1:52 am

Philip

Was this the (in)famous ITA. (Initial Teaching Alphabet)? Whatever happened to it?

Philip Taylor said,

May 5, 2022 @ 3:32 am

No, the ITA was an attempt to spell British English phonetically without introducing the complexity and fine distinctions that characterise the IPA. The synthetic phonics alphabet differs only in pronunciation from the standard English alphabet, and therefore has 26 letter/sounds (graphemes/phonemes) whilst the ITA had between 43 and 45. The Wikipedia chart conveys this very well. As to what happened to it, Wikipedia says "Any advantage of the I.T.A. in making it easier for children to learn to read English was often offset by some children not being able to effectively transfer their I.T.A.-reading skills to reading standard English orthography, and/or being generally confused by having to deal with two alphabets in their early years of reading", and that accords well with my own recollections and beliefs. Unfortunately the one friend who could offer first-hand insights into the launch and decline of the ITA had a fall yesterday, and is currently in hospital …

Peter Grubtal said,

May 5, 2022 @ 11:39 am

Thanks, Philip

It was one of a number of bright ideas of the sixties, like teaching kids arithmetic through group theory. My, perhaps cynical, take on it was that all these educational institutes had to come up with something to justify their existence.

Philip Taylor said,

May 5, 2022 @ 1:09 pm

I gave maths tuition to a young girl (maybe 10 years of age) during the late 1980s. She was fine with group theory, but long division was a complete mystery to her.

julie lee said,

May 9, 2022 @ 12:39 am

I'm a true believer in synthetic phonics. Here's my experience for what it's worth:

I had to take care of my 4-year-old grandson because his mother had separated from his father and had to work fulltime at her

banking job. We moved from Chicago to London and put the boy in a top school there. In Chicago he was still learning the alphabet. In his London class the 4-to-5-year-old children were already reading books. He was illiterate. How was he ever to catch up? I was very worried, but the teacher told me: "Don't worry. We've had some children from America just like him, and they caught up quickly." "Really?" I said doubtfully.

The teacher then introduced me to synthetic phonics and gave me a story book to read with my grandson using synth. phonics. I was told to start the book in few days, after the boy had learned syn. phonics in class. Well in a few days I started reading the book with him. I had

him read each word with phonics. We went along smoothly until we came to the word "only". He read it saying: "ɔ –nə — lə– ee, ɔ– nə — lə– ee", a few times and I thought "He's not going to get it," and suddenly he said, "Only !" I was amazed. Then we went along smoothly with other words until we came to the word "water", and

I thought, "Oops, he's not going to get this one." He read: "wə– æ –tə — rə, wə– æ –tə — rə" a few times and then suddenly: "Water!" I was amazed the human mind could jump like this. Of course, things went very fast after that, and very quickly he was caught up with the class. So the teacher was right after all. Long live syn. phonics !