…"such matters as Opinion, not real worth, gives a value to"

« previous post | next post »

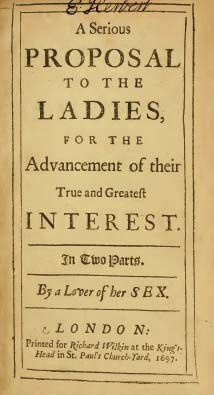

Recently, a series of serendipitous connections led me to read Mary Astell's work, A serious proposal to the ladies, for the advancement of their true and greatest interest, first published in 1694. And this experience led me to two questions, the first of which is, Why in the world are Mary Astell's works not available in a readable plain text form, from sources like Project Gutenberg and Wikisource?

Recently, a series of serendipitous connections led me to read Mary Astell's work, A serious proposal to the ladies, for the advancement of their true and greatest interest, first published in 1694. And this experience led me to two questions, the first of which is, Why in the world are Mary Astell's works not available in a readable plain text form, from sources like Project Gutenberg and Wikisource?

Astell's Wikipedia entry explains that she "was one of the first English women to advocate the idea that women were just as rational as men, and just as deserving of education." And she is important enough to merit an entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, which describes at length her contributions to metaphysics and epistemology.

I know that the first-order reason for this lacuna is that OCR is still pathetically incapable of dealing with 17th-century printing, and that no volunteers have stepped forward to transcribe her writings from the available paper or image sources. But this doesn't really answer the question, it just moves it back a step.

Anyhow, my second question is one that I've wondered about before, without ever trying to find an answer: Why did authors from Astell's time distribute initial capital letters in the apparently erratic way that they did?

Here's the first sentence of A Serious Proposal to the Ladies:

LADIES, SInce the Profitable Adventures that have gone abroad in the World have met with so great Encouragement, tho' the highest advantage they can propose, is an uncertain Lot for such matters as Opinion, not real worth, gives a value to ; things which if obtain'd are as fitting and fickle as that Chance which is to dispose of them ; I therefore persuade my self, you will not be less kind to a Proposition that comes attended with more certain and substantial Gain ; whose only design is to improve your Charms and heighten your Value, by suffering you no longer to be cheap and contemptible.

In that sentence there 10 nouns with initial capitals (Adventures, World, Encouragement, Lot, Opinion, Chance, Proposition, Gain, Charms, Value) and 4 with initial lower-case letters (advantage, worth, value, things). There's also one adjective with initial capitalization (Profitable), and 10 with initial lower-case letters (highest, uncertain, real, fitting, fickle, kind, certain, substantial, cheap, contemptible).

Here's the last sentence of Part 1:

To close all, if this Proposal which is but a rough draught and rude Essay, and which might be made much more beautiful by a better Pen , give occasion to wiser heads to improve and perfect it, I have my end. For imperfect as it is, it seems so desirable, that she who drew the Scheme is full of hopes , it will not want kind hands to perform and compleat it. But if it miss of that, it is but a few hours thrown away, and a little labour in vain, which yet will not be lost, if what is here offer'd may serve to express her hearty Good-will, and how much she desires your Improvement, who is LADIES, Your very humble Servant.

In that passage there are 7 nouns with initial capitals (Proposal, Essay, Pen, Scheme, Good-will, Improvement, Servant) and 8 with initial lower-case letters (draught, heads, end, hopes, hands, hours, labour, vain). All 9 adjectives have initial lower-case letters (rough, rude, beautiful, better, imperfect, desirable, kind, hearty, humble).

And a representative bit from page 6:

And sure, I shall not need many words to persuade you to close with this Proposal. The very offer is a sufficient inducement, nor does it need the set-offs of Rhetorick to recommend it, were I capable, which yet I am not, of applying them with the greatest force. Since you can't be so unkind to your selves, as to refuse your real Interest, I only entreat you to be so wise as to examine wherein it consists ; for nothing is of worse consequence than to be deceiv'd in a matter of so great concern.

Here we have 3 nouns with initial caps (Proposal, Rhetorick, Interest) and 8 without (words, offer, inducement, set-offs, force, consequence, matter, concern). [And never mind, for now, Astell's italicization choices…]

Adding up the totals from the three passages, we get 10+7+3=20 nouns with initial capital letters, and 4+8+8=20 nouns with lower case letters. The choice seems to be partly a matter of emphasis or contrast, and partly a matter of substance, and partly a matter of chance — a bit like intonational pitch modulation?

A bit of research turned up only one serious study of this question: N. E. Osselton, “Spelling-Book Rules and the Capitalization of Nouns in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries”, In Historical and Editorial Studies in Medieval and Early Modern English, ed. Arn M.J. et al., 49–61, 1985.

I haven't yet obtained a copy, but I found some quotes and summaries in various online sources. Thus from Alan Levinovitz, "'Dao with a Capital D': A Study iin the Significance of Capitalization", Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 2015:

In one of the only extant studies of English letter-case usage, N. E. Osselton observes, “The reader of facsimiles or of original texts printed between 1550 and 1800—and perhaps especially those from the middle part of the seventeenth century—is constantly aware that the initial capitals mean something, though he may be at a loss to define precisely what it is they do mean”.

And from Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Introduction to Late Modern English, 2009:

The use of extra initial capitals, according to Osselton, steadily increased during the first half of the eighteenth century to about 100 per cent around the 1750s after which this practice was drastically reduced and, fifty years later, abandoned completely. The reason for giving up the practice to capitalise all nouns was pressure from writers, who felt that they could not longer make use of capitals to emphasize individual words, as they had been accustomed to do before such idiosyncratic use of capitals was standardised by the printers.

There's obviously much more to say about this question, but that's all I have time for this morning.

AKMA said,

November 20, 2016 @ 8:30 am

Could there be a typographic reason, namely, that if the printer were running out of lower-case letters, he might substitute an upper-case letter at the beginning of another word on the page?

[(myl) I'm not sure about that — but van Ostade also writes that

In eighteenth-century manuscripts, it is not always easy to distinguish between capitals and lower-case letters, and giving every noun its capital would have saved typesetters a lot of time.

]

Bloix said,

November 20, 2016 @ 8:37 am

To answer this question, wouldn't it help to look at German and other European languages? German, of course, capitalizes all nouns, and google tells me that Dutch did, too, until 1948, and that Swedish did in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Dick Margulis said,

November 20, 2016 @ 8:56 am

I think the story is somewhat more complicated than AKMA suggests, but there's some merit in that point.

The relationships among writing, editing, and typesetting were not always what they are now. Publishing evolved from printing, in the sense that early printers were wont to select the texts that they wanted to print, for the most part (initially, of course, selecting works that already existed). The printers employed correctors (what we would call proofreaders), who were not really editors but who tended to be scholars in their own right.

In the late seventeenth century, most publishers still operated with the assumption that writers knew their craft and that the manuscript was okay as submitted. That is, they were not in the business of editing the manuscript before composition. On the other hand, the compositors, who, after all, had to decipher handwriting with words crossed out and inserted, ink spots that might or might not be punctuation marks, and so forth, had evolved into the keepers of the rules, as it were, of spelling, punctuation, and syntax; and they corrected on the fly, some of them better than others. In other words, what we now carve off into copyediting was something the compositor was doing.

Meanwhile, the correctors had evolved into proofreaders whose job it was to, not only to mark up galleys for typographic errors but also second-guess the compositors in their interpretation of the text.

Authors, for the most part, had no say in what happened to their text after it went to the publisher. So while authors may have had opinions that varied over time with respect to capitalization, I don't think we can say from this remove that the capital letters we see in printed text from that era faithfully represent authors' writing styles. Like as not, they represent fashions in the printers' chapels; and even within that subculture, individual chapels and individual journeymen may have been more or less consistent than others in their application of the rules, such as they were.

tl;dr: "Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity"

Cervantes said,

November 20, 2016 @ 9:16 am

Mark:

Noel Osselton studied early English spelling for decades. Re capitalization (in the work you cite) he categorized (and, in some cases, deduced) two primary "rules." The first was entirely subjective: a simple matter of using initial capitals where the author, publisher, or printer wanted to draw attention or place emphasis; and the second "rule" was to use them, by convention, with certain semantic categories: animate nouns, such as "Philosopher"; names of disciplines, such as "Grammar"; names of physical objects, such as "House"; and certain abstract nouns, such as "Knowledge." This last category ("certain abstract nouns") is clearly vague (if you see what I mean) and I recall that Osselton was a little more analytical about it — but I don't recall the details. He did point out that if these rules were, indeed, rules, they weren't always obeyed; and that even some 18th-century orthographers acknowledged that writers (etc.) were to be afforded some leeway.

In addition to the article you cited, you might look for Osselton's "Informal spelling systems in Early Modern English: 1500-1800," published in English Historical Linguistics: Studies in Development, Blake and Jones (eds.), 1984.

Stephen Goranson said,

November 20, 2016 @ 9:39 am

There is a reprint of the book at Hathi Trust (NY: Source Book Press, 1970) available in full view.

Note: "Unabridged republication of the 1701 London edition … obvious typographical errors … have been corrected…."

https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/007513959?type%5B%5D=title&lookfor%5B%5D=serious%20proposal%20to%20the%20ladies%2C%20for%20the%20advancement%20of%20their%20true%20and%20greatest%20&ft=ft

James said,

November 20, 2016 @ 10:00 am

I think it's related to A. A. Milne's extra capitalizations that plainly indicate something like importance, but not exactly — something hard to pin down but easy to get a feel for. E.g.,

Text here.

Robert Coren said,

November 20, 2016 @ 11:09 am

@James: Well, Milne made frequent use of this device for humorous effect, and I'm pretty sure he was not alone, although he may have been responsible for its continued popularity today. (Alert — or obsessive –readers may have noticed that I myself used capitalization in this manner in a Language Log comment in the past day or two.)

Y said,

November 20, 2016 @ 2:29 pm

I'd say capitalized nouns are those that are prominent when read aloud. Note that at least through Victorian times reading books aloud to one another was common. Even if capitalization was not added consciously as hints to reading aloud, it's likely that writers were imagining their words being read aloud as they were writing them, and reflecting that in their orthography.

Viseguy said,

November 20, 2016 @ 5:28 pm

I wonder if this question has been studied specifically with reference to the American Declaration of Independence, which is rife with such seemingly arbitrary capitalizations. Take, for instance: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, …". The first instance of "men" is not capitalized, but the second is. The first instance of "Rights" is capitalized, but not the second. Go figure. The theory of spoken emphasis seems the most likely to me on its face, but it doesn't really fit. (Why not capitalize "truths"? Or "self-evident"?) Could it be that people did whatever the hell they pleased? As a non-linguist, I confess that's my working assumption.

Rubrick said,

November 20, 2016 @ 6:29 pm

It feels very similar to me to the sometimes random-seeming use of bolded words in comics. (Similar, probably, because in neither case has my brain fully acclimated to it, unlike italics, which I feel I intuitively register the sense and sound of, even though I'd be hard pressed to put my finger on exactly what it conveys.)

AG said,

November 21, 2016 @ 2:58 am

When I first read Pynchon's "Mason & Dixon" his olde-timey capitalization seemed very arbitrary to me, but in retrospect I think that was in comparison with the German I was studying at the time – and now I realize that writers from that era in English were often pretty arbitrary themselves. (for what it's worth here's the first sentence of "Mason & Dixon", where he really went all out:)

"Snow-Balls have flown their Arcs, starr'd the Sides of Outbuildings, as of Cousins, carried Hats away into the brisk Wind off Delaware,– the Sleds are brought in and their Runners carefully dried and greased, shoes deposited in the back Hall, a stocking'd-foot Descent made upon the great Kitchen, in a purposeful Dither since Morning, punctuated by the ringing Lids of Boilers and Stewing-Pots, fragrant with Pie-Spices, peel'd Fruits, Suet, heated Sugar,– the Children, having all upon the Fly, among rhythmic slaps of Batter and Spoon, coax'd and stolen what they might, proceed, as upon each afternoon all this snowy December, to a comfortable Room at the rear of the House, years since given over to their carefree Assaults."

maidhc said,

November 21, 2016 @ 3:12 am

I read a lot of material written by non-native English speakers. Random and inconsistent capitalism of nouns seems to be a common feature. (These are people whose native languages are written with different alphabets that do not have upper- and lower-case.) I suppose they see English that has a few capital letters sprinkled in it and take it to be a matter of aesthetics rather than following rules.

Am I correct in saying only Western European, Cyrillic and Greek have upper- and lower-case? No, it turns out also Armenian, Coptic and some varieties of Georgian. They are called "bicameral" scripts. These seem to be all.

I do know something about bolding in comics. Text in comics is conventionally all upper-case. I don't know exactly why, but it goes back more than a century. Upper-case text blocks are considered to be hard to read because all the letters are a uniform size. Bolding is introduced to break up the uniformity. In some cases it may coincide with emphasis, but basically the important thing is a uniform distribution throughout the text.

flow said,

November 21, 2016 @ 10:01 am

@maidhc—there's an interesting list at http://rishida.net/blog/?p=1847. Funny to see how much for granted we take that upper case / lower case thing when it only came into being at some point during the middle ages, and so few writing systems in the world have it.

BZ said,

November 21, 2016 @ 10:14 am

Although Cyrillic has capitalization, its (at least Russian) rules are different from English. While proper names are capitalized, adjectival forms of proper nouns are not, unless the adjective in question is part of the proper noun phrase, so "Russia" is capitalized as a noun. "Russian" in "Russian Federation" is capitalized because it's part of a proper name, but not in the "Russian ruble" because it's an adjectival form not part of a proper name. Month names and days of the weeks are also not capitalized. In names of books (and other publications?) only the first word is capitalized. Pronouns are not capitalized, despite what Wikipedia would have you believe, unless they refer to God (and even then I'm not sure).

I am writing this from memory, so I may have missed some subtleties, but anyway, it is entirely easy to believe that Russians (lowercase by the way) who learn English will have problems with capitalization.

Robert Coren said,

November 21, 2016 @ 10:33 am

@BZ: I know that neither French nor German capitalizes adjectival forms of proper nouns, and I wouldn't be surprised if that's true of a bunch of other European languages.

Robert Coren said,

November 21, 2016 @ 10:37 am

I'm having a vague childhood memory of a novel by T. H. White called Mistress Masham's Repose, in which the protagonist, a 20th-century English girl, encounters a society of Lilliputians who speak as they would have done (and as they would have been written) in Swift's time; at one point, after she's listened to a long speech from one of them that's written with the kind of capitalization discussed here, she is described as having "her head buzzing with capital letters".

Dick Margulis said,

November 21, 2016 @ 10:55 am

@flow: "Funny to see how much for granted we take that upper case / lower case thing when it only came into being at some point during the middle ages."

An easy slip to make, and not your main point, but the upper case and lower case did not exist until the 16th century. Before that we had majuscules (derived primarily from Roman square capital letters, so-called because they were carved in stone on capitals) and minuscules (derived from less formal handwriting). But cases came into existence with the invention of moveable type as a way to keep the letters sorted, and the bicameral arrangement of upper and lower cases originated in what is now Belgium in 1563 (I'd surmise by Christophe Plantin in Antwerp), according to Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Letter_case#Type_cases).

Adam F said,

November 21, 2016 @ 10:56 am

The thing I found most bizarre in the transcription was the double-capital in "SInce", but the linked PNG makes some sense of it.

Jonathan said,

November 21, 2016 @ 12:00 pm

French apparently has a rule directly contrary to English's preference for capitalizing Nouns, and not adjectives. According to this:

En français de France, la norme est : Premier ministre et ministre de l’Intérieur

Why? Because:

Ce sont les entités, les administrations, qui sont importantes ; pas les individus qui exercent quelque temps des fonctions d’État.

flow said,

November 21, 2016 @ 2:06 pm

@Dick Margulis—yeah, well, I wasn't talking about upper and lower wooden cases here but about the fact that modern Latin script has two distinct series of letters, and you confirm what I think, namely that those two series were not in existence by the time of, say, Caesar, but they were in existence already by the time movable type got invented (around 1450). That's one side of the question, the letter shapes proper; the other side is whether they were taught and used in a form comparable to the modern bicameral system, and this is somewhat harder to tell, I'd say.

Coming to think of it, I'd want to remark that the Japanese Kana—which are not listed by Richard Ishida—may be considered a bicameral script as well. There's one important difference, though, in that you cannot, in accepted orthography, write e.g. the very first mora of a word in katakana and the rest in hiragana; other than that, Kana are as close to a bicameral system as it gets.

And let's not forget that around 1700, as metioned by @Bloix, not only was capitalization a common phenomenon in central and northern Europe, but so was the use of Blackletter (Fraktur), which was very often mixed with 'Roman' / 'round' / 'Antiqua' (not sure what to call the ordinary shapes) letters. Indeed, Germans up until around the 1950s habitually used a quadricameral writing system.

Brian said,

November 21, 2016 @ 4:51 pm

Why are all these books not at Project Gutenberg…

I think that I can answer that. Distributed Proofreaders, who supply the majority of books that go to PG, are volunteers and there are are very few of them. They do the best they can, but a few hundred people can not cope with the millions of books that need to be preserved and converted to readily available eBooks.

If you wish to see your personal favourites at PG, then maybe volunteering a few minutes of your time each day to learn the necessary skills that are needed to get these books prepared, would be a step in the right direction.

Don't complain about the problem start helping to solve the problem.

Many skills are needed, including programmers to keep the site and the tools up-to-date as well as the more obvious skills. We need people that are competent in all the European languages and the classics as well as people that can cope with many of the day to day problems mentioned above.

Check it out you might find it a fun and useful thing to do?

http://www.pgdp.net or one of the similar organisations that are trying hard to save these books in electronic form before the paper and ink versions become even more unreadable due to their age. Even many quite recent books were printed on very poor quality paper and even the best of paper needs conditions that is not conducive to letting the reading public access to most of these books! Freely distributed eBooks are an effective way to extend the readability of these books, OCR is getting better, but it still need the assistance of humans to stop the "lost in translation" type scannos and all the other small tasks required to change dead tree books to eBooks.

A few minutes a day at Distributed Proofreaders or even volunteering to scan books at TIA or any of the other archive would certainly help.

Thank you.

DWalker07 said,

November 22, 2016 @ 10:40 am

I often find that I *want* to read early text like this one; they ought to be interesting… and yet, it's hard to get past the issue that … the writing sure does take a long time to say anything.

Andreas Johansson said,

November 22, 2016 @ 11:38 am

@BZ

The capitalization rules you describe for Russian sound to be essentially identical to those for Swedish (which of course uses the Latin alphabet). Capitalization of words referring to God is inconsistent in Swedish (incl the word gud/Gud "God" itself).

J.W. Brewer said,

November 22, 2016 @ 5:02 pm

The analogy I sometimes find useful for kana is that katakana is what you get when you put hiragana into italics. The contrast between "regular" type and italics (or boldface etc) in our alphabet is perhaps bicameralism along a different dimension that upper-case v lower-case (and does go back to the days of hand-set type), but I don't know if it has its own conventional name amongst theorists of typography. And of course what sorts of things do and don't get italicized in the middle of regular text is also the sort of thing where stylistic conventions in English have evolved over time and you can sometimes create an archaic/period atmosphere by doing it when it would be unexpected under the modern conventions.

David Marjanović said,

November 22, 2016 @ 7:26 pm

That's Danish, not Dutch.

French capitalizes all nouns as its form of headline capitalization. German doesn't have any such thing.

The use in the US Constitution & Declaration of Independence seems to me to be a combination of emphasis – though it's not always intuitive to me – and respect, e.g. Government, compare État in French.

Joanna Bujes said,

November 27, 2016 @ 1:32 pm

Someone ought to do a study of modern marketing practices in advertising copy, which also uses capitalization throughout, though I am not sure whether there's a method per se. I don't read ads as a rule, but twenty years ago, I was working for a software company and was asked to proof ad copy. Almost every noun was capitalized. Funny.

James Wimberley said,

November 27, 2016 @ 1:44 pm

The US Constitution liberally uses initial capitals. Sample:

"The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States; but all Duties, Imposts and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States.."

It's a nice question for original-intenters what the capitalisation conveys. What might the differences be between "general welfare", "General Welfare", and "general Welfare"? And is there any significance in the odd "Power To"? At the end, "United States" is different from "united States", as it creates the name of a country.

James Wimberley said,

November 27, 2016 @ 1:54 pm

PS: Article III.1 creates a "supreme Court", not the Supreme Court. So the Congress could have called it something else.

James Wimberley said,

November 27, 2016 @ 2:01 pm

PS2: The Bill of Rights is markedly less capitalised. The third, eighth, ninth and tenth Amendments are entirely uncapitalised except for the first letters of the sentence.

Source of transcripts: the National Archives.

James Wimberley said,

November 27, 2016 @ 2:06 pm

PS3:: Oops, I was looking at the joint resolution, not the adopted text. Only the eighth adopted amendment is entirely uncapitalised. But it still holds that the capitalisation is light compared to that in the Constitution.