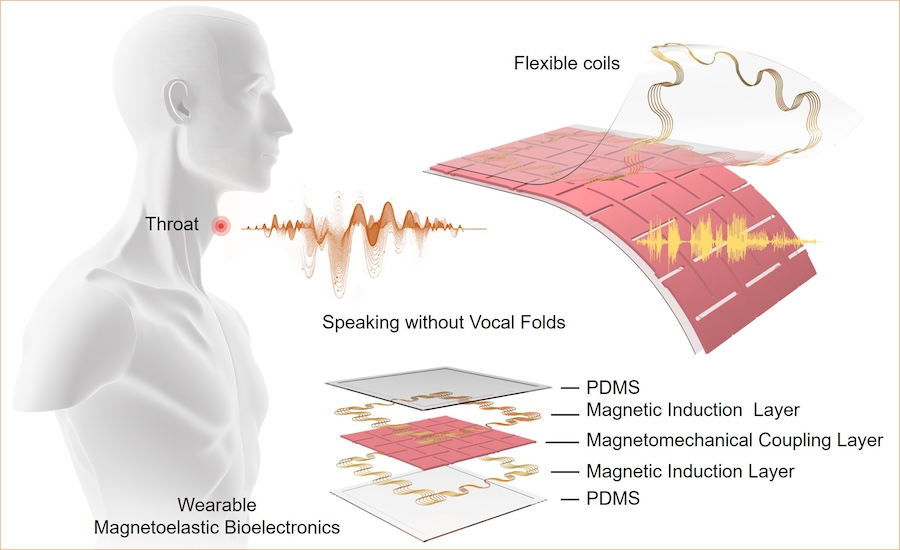

This post is another pitch for our on-going effort to develop simple, easy, and effective ways to track neurocognitive health through short interactions with a web app. Why do we want this? Two reasons: first, early detection of neurodegenerative disorders through near-universal tracking; and second, easy large-scale evaluation of interventions, whether those are drugs or lifestyle changes. You can participate by enrolling at https://speechbiomarkers.org, and suggesting it to your friends and acquaintances as well.

Today, diagnosis generally depends on scoring below a certain value on cognitive tests such as the MMSE, which usually won't even be given until you've started experiencing life-changing symptoms — and at that point, the degenerative process has probably been at work for a decade or more. This may well be too late for interventions to make a difference, which may help explain the failure of dozens of Alzheimer's disease drug trials. And it's difficult and expensive to evaluate an intervention, in part because it requires a series of clinic visits, making it hard to fund support for trials that don't involve a patented drug.

If people could accurately track their neurocognitive health with a few minutes a week on a web app, they could be alerted to potential problems by the rate of change in their scores, even if they're many years away from a diagnosis by today's methods. Of course, this will be genuinely useful only when we have ways to slow or reverse the process — but the same approach can be used to evaluate such interventions inexpensively on a large scale.

More background is here: "Towards tracking neurocognitive health", 3/24/2020. As that post explains, this is just the first step on what may be a long journey — but we will be making the data available to all interested researchers, so that the approaches that have worked elsewhere in AI research over the past 30 years can be be applied to this problem as well.

Again, you can participate by enrolling at https://speechbiomarkers.org . And please spread the word!

Read the rest of this entry »