The evolution of metaphors?

« previous post | next post »

Today's Frazz has a nice metaphor about life cycles:

Which called to mind an odd (to me) new theory about the language of Neanderthals, presented in a 5/20/2024 review essay by Stephen Mithen, "How Neanderthal language differed from modern human – they probably didn’t use metaphors":

[T]he evidence points to key differences in the brains of our species and those of Neanderthals that allowed modern humans (H. sapiens) to come up with abstract and complex ideas through metaphor – the ability to compare two unrelated things. For this to happen, our species had to diverge from the Neanderthals in our brain architecture.

Some experts interpret the skeletal and archaeological evidence as indicating profound differences. Others believe there were none. And some take the middle ground. […]

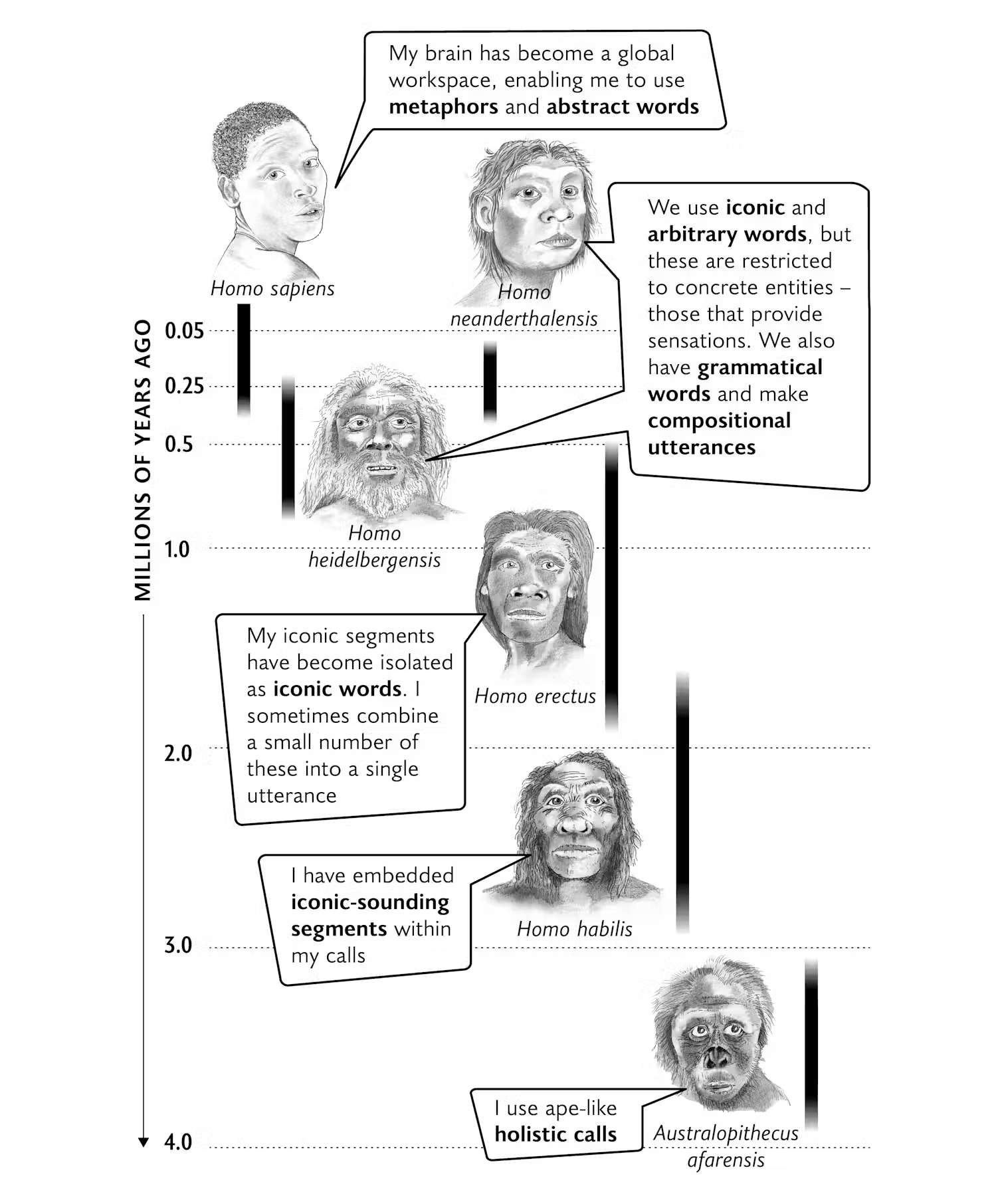

While it may be possible to join the puzzle pieces in several different ways, my long wrestle with the multi-disciplinary evidence has found only one solution. This begins with iconic words being spoken by the ancient human species Homo erectus around 1.6 million years ago.

As these types of words were transmitted from generation to generation, arbitrary words and rules of syntax emerged, providing the early Neanderthals and H. sapiens with equivalent linguistic and cognitive capacities.

But these diverged as both species continued to evolve. The H. sapiens brain developed its spherical form with neural networks connecting what had been isolated semantic clusters of words. These remained isolated in the Neanderthal brain. So, while H. sapiens and Neanderthals had equivalent capacity for iconic words and syntax, they appear to have differed with respect to storing ideas in semantic clusters in the brain.

By linking up different clusters in the brain that are responsible for storing groups of concepts, our species gained the capacity to think and communicate using metaphor. This allowed modern humans to draw a line between widely different concepts and ideas.

This was arguably the most important of our cognitive tools, enabling us to come up with complex and abstract concepts. While iconic words and syntax were shared between H. sapiens and Neanderthals, metaphor transformed the language, thought and culture of our species, creating a deep divide with the Neanderthals. They went extinct, while we populated the world and continue to flourish.

This is far from my areas of specialization, but I've never been convinced that "Neanderthals" (and Denisovans) are actually a separate species from H. sapiens. See this paper for a recent consideration of the issues, which ends up supporting the traditional taxonomic ideas despite presenting lots of contrary evidence — and this article for a more contrary view…

And I'm even more skeptical of the idea that the (relatively modest) differences in (the distribution of measururements of) skull endocasts point to the development of metaphors as a determinative difference, especially given the large (and underdocumented) variation in endocast measures in H. sapiens across space and time. Other kinds of skull measurements were a big deal for 19th-century racist anthropologists, and as a result, the topic has largely been shunned by modern researchers. [What little modern work has been done, e.g. the "Open Research Scan Archive" (ORSA) at the Penn Museum, does not seem to be available to researchers…]

In any case, here's Mithin's illustration of hominin language evolution:

This is a step forward over the position of Lieberman & Crelin, "On the speech of Neanderthal Man", Linguistic Inquiry 1971 — which concluded, also on the basis of skull measurements and endocast properties, that

We have previously determined by means of acoustic analysis that Newborn humans, like nonhuman primates, lack the anatomical mechanism that is necessary to produce articulate speech. That is, they cannot produce the range of sounds that characterizes human speech. We can now demonstrate that the skeletal features of Neanderthal man show that his supralaryngeal vocal apparatus was similar to that of a Newborn human. […]

Neanderthal man did not have the anatomical prerequisites for producing the full range of human speech. He probably lacked some of the neural detectors that are involved in the perception of human speech. He was not as well equipped for language as modern man. His phonetic ability was, however, more advanced than those of present day nonhuman primates and his brain may have been sufficiently well developed for him to have established a language based on the speech signals at his command. The general level of Neanderthal culture is such that this limited phonetic ability was probably utilized and that some form of language existed.

And its a bigger advance over the original view of Neanderthals as subhuman scavengers. One step at a time…

Jerry Packard said,

June 7, 2024 @ 7:50 am

This would appear to be at odds with Cormac McCarthy’s insight that our ancestors became our cognitive ancestors when they had the insight that “… what he had just understood is that one thing can be another thing. Not look like it or act upon it. Be it. Stand for it. Pebbles can be goats. Sounds can be things. The name for water is water. What seems inconsequential to us by reason of usage is in fact the founding notion of civilization. …” From _Stella Maris_.

McCarthy first wrote about this insight in "The Kekulé Problem", a 2017 essay. I have appreciated that insight in working on a theory of language origin and development that posits homo erectus as the first speaker.

David Marjanović said,

June 7, 2024 @ 9:39 am

What a strange… metaphor.

That doesn't follow even from the metaphor.

This is only a meaningful sentence after you've picked one of the 150 or so definitions of "species". They have nothing in common other than that word. Numerous attempts to find things in common have only resulted in… even more definitions.

Mark Liberman said,

June 7, 2024 @ 10:30 am

@David Marjanović: "This is only a meaningful sentence after you've picked one of the 150 or so definitions of "species"."

It's true that species (like language) is a problematic concept. But if the assumption were (as it often has been) that (under some unspecified definition) "caucasians" and "asians" or "africans" or "pygmies" or other "morphologically distinct (but hybridizing)" group are separate species, might your reaction be different?

Jerry Packard said,

June 7, 2024 @ 11:31 am

But at the very least, ‘species’ as used here is a useful heuristic.

TonyK said,

June 7, 2024 @ 11:31 am

This is purest fantasy! It reminds me of Percival Lovell's stubborn conviction that Mars was criss-crossed with the canals of an alien civilization: drawing huge conclusions from imagined evidence.

Philip Taylor said,

June 7, 2024 @ 11:46 am

http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/myl/MithinLanguageEvolutionFigure.avif does not render here — is there any reason to use such an unusual file type as ".avif" in preference to a more common one ?

Mark Liberman said,

June 7, 2024 @ 12:24 pm

@Philip Taylor: "is there any reason to use such an unusual file type as ".avif" in preference to a more common one ?"

It's that way in the original from Mithin's essay.

And AVIF is a standard format, now supposedly available almost everywhere, so you should update your browser/OS/whatever…

Anyhow, here's a .png version.

Peter Grubtal said,

June 7, 2024 @ 1:11 pm

Science and scientific investigation has fascinated me all my life, but when I see stuff like this, I just hope that it wasn't produced using public money.

These speculations are at the wit of anybody, and hard data to back them up is non-existent.

Jonathan Smith said,

June 7, 2024 @ 1:33 pm

Well according to Sukuki (2018), "the calls that [Japanese] tits [= Parus minor] give when and only when encountering predatory snakes are considered 'functionally referential' because they elicit specific anti-snake behaviors in receivers"… the author's experiments/results are interpreted to mean that "simply hearing these calls causes tits to become more visually perceptive to objects resembling snakes (moving sticks)" (p. 1541). There are spectrograms of 'snake y'all' in tit (:D) but sadly no audio file that I see… it would be surprising though if the call were demonstrably "iconic" in nature, potentially putting tits ahead of Homo erectus on the language development continuum?

Jonathan Smith said,

June 7, 2024 @ 1:35 pm

*Suzuki, sorry

Mark Liberman said,

June 7, 2024 @ 2:31 pm

@Jonathan Smith: "according to Sukuki (2018), 'the calls that [Japanese] tits [= Parus minor] give when and only when encountering predatory snakes are considered 'functionally referential' because they elicit specific anti-snake behaviors in receivers'"…

Long before that, Bob Seyfarth and Dorothy Cheney documented a suite of variously referential alarm calls in Vervet monkeys — see this 1980 paper and their 1990 book (summarized here).

Rick Rubenstein said,

June 7, 2024 @ 6:07 pm

This essay looks like a an outsanding example of speculative hogwash.

As for whether we and Neandertals are the same species, I think this question is in the same category as "Is Pluto a planet?". Some bodies orbit each other. Some groups of organisms diverge. In neither case does nature give a damn whether it adheres to our arbitrary and inadequate nomenclature.

Philip Taylor said,

June 8, 2024 @ 5:22 am

[OT: ."avif"] — thank you for the PNG version, Mark. As to "AVIF is a standard format, now supposedly available almost everywhere", I suppose it all depends on what you mean by "standard" (as one would expect in a forum devoted to language and linguistics). According to W3techs.com (which, despite its name, almost certainly has nothing to with the W3C), the market penetration of .avif is 0.2% — the only format with lower market penetration is .bmp at 0.1%. Jpegs, on the other hand, have 77.1% and PNGs even greater at 81.6% — I will therefore leave my browser/OS/whatever unchanged, as they are perfect for 99.9% of my needs — I can always call on Firefox (my fallback browser) for the 0.1% of sites that Seamonkey cannot render as intended.

Julian said,

June 8, 2024 @ 7:44 pm

[reliving the day's excitement around the campfire]:

"And that mammoth came at me like a steam train!"

Jerry Packard said,

June 9, 2024 @ 7:13 am

"And that mammoth came at me like a calving glacier”