Genes and tone languages, yet again

« previous post | next post »

Below is a guest post by Bob Ladd.

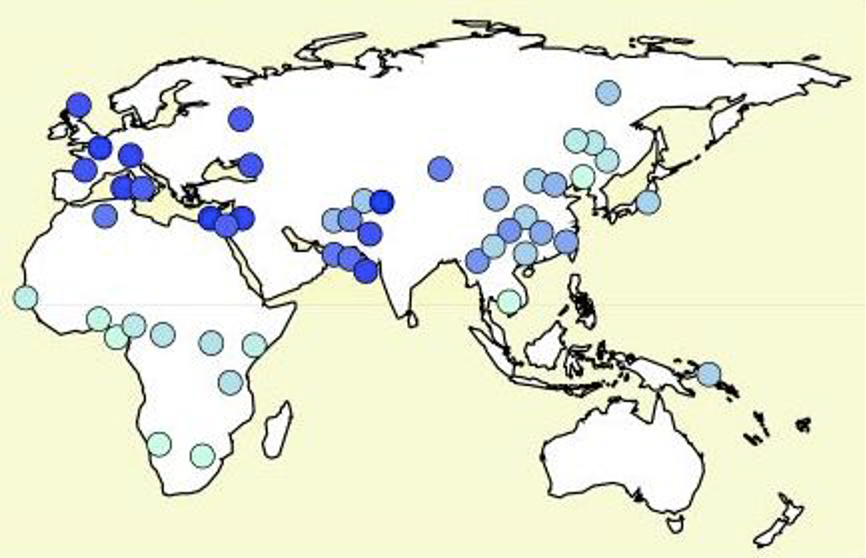

Long-time readers of Language Log may recall a couple of posts from 2007 (here and here) about a possible link between population genetics and tone languages. That year, Dan Dediu and I published a paper in PNAS showing that there’s a significant geographical correlation between the distribution of tone languages and the distribution of older and newer variants (alleles) of two genes known to be involved in brain development, ASPM and Microcephalin 1. For ASPM in the Old World (where tone languages are found predominantly in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia), you can eyeball the correlation on the map below: the lighter the dot, the rarer the new variant of the gene. Our PNAS paper put this eyeballing on a reasonably sound statistical basis.

However, all we did was demonstrate a correlation, and lots of people were ready to remind us that “correlation is not causation”. There were also plenty of other people who wanted nothing to do with the idea that genetic differences might have anything to do with language typology at all. There were more than a few interestingly awkward conversational silences when I attended the ICPhS meeting in Saarbrücken later that summer.

But the idea that small biological variations might have an influence on language keeps surfacing. For example, a much more recent Language Log post (here) discussed the suggestion that changes in dentition (possibly due to the spread of agriculture) may have led to an increase in the use of labiodental sounds in the languages of the world. And coming back to tone languages, a few months ago Patrick Wong and his colleagues in Hong Kong published direct experimental evidence that individual genetic makeup with regard to ASPM has an effect on the way individuals deal with linguistic tone.

Their study was based on more than 400 native speakers of Cantonese, who were genotyped for ASPM and Microcephalin 1 and for several other genes (such as FOXP2 and CNTNAP) which have previously been shown to have some involvement with language. The speakers performed a simple-seeming task that required them to discriminate Cantonese pseudo-words that differed only in lexical tone. Wong and his colleagues found that carriers of the new allele of ASPM had worse average performance than those not carrying it. None of the other genes tested (including Microcephalin 1) had any effect on the outcome. (Wong et al., "ASPM-lexical tone association in speakers of a tone language: Direct evidence for the genetic-biasing hypothesis of language evolution", Science Advances 2020.)

Whether you were interested or dismissive when Dediu and I started speculating about genes and tone languages back in 2007, Wong’s results are harder to ignore than a mere correlation. We’ve recently posted a new paper to PsyArXiv putting his study in the context of our original proposal. We think his work is a potentially important step in our developing understanding of the biological bases of human language.

Above is a guest post by Bob Ladd.

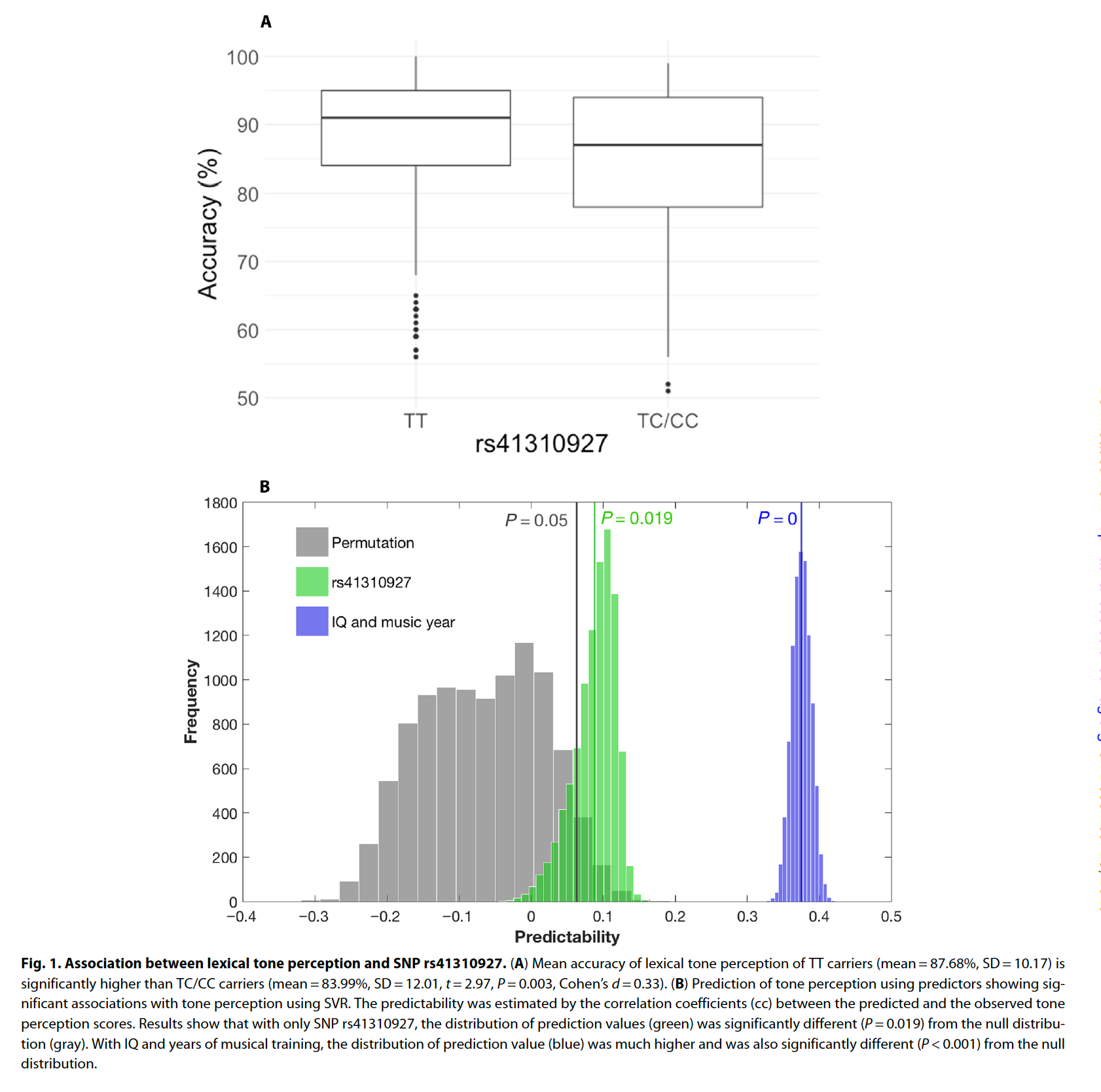

For a more quantitative graphical summary of the results of Wong et al. 2020, see their Figure 1:

Philip Taylor said,

December 23, 2020 @ 9:57 am

"There were also plenty of other people who wanted nothing to do with the idea that genetic differences might

have anything to do with language typology at all". There are plenty of people who want nothing to do with

the idea that genetic differences might have anything to do with anything in the real world, because

if genetic differences could be shewn to make a difference we would have to completely re-assess our

idea of what it is, and what it is not, acceptable to suggest. Back in Galileo's day, it was completely

unacceptable to suggest that the Earth might rotate around the Sun. But times moved on, and today that is

the received wisdom. Keep up your research, no matter how much the PC brigade might seek to dismiss it,

and in 400 years or so your ideas may well be as mainstream as Galileo's are today.

Bob Ladd said,

December 23, 2020 @ 10:21 am

@ Philip Taylor: Quite apart from what "the PC brigade" may think, there are genuinely troubling ethical issues related to research on genetic effects on behavior, personality, cognition, and so on, not the least of which is how easy it is for such research to be distorted and misused in pursuit of ideologies of superiority of one group over another. The original 2005 papers on the distribution of the old and new alleles of ASPM and Microcephalin by Bruce Lahn's research group, which is what originally alerted Dediu and me to the overlap with the distribution of tone languages, were misused on social media in just this way.

More specifically, though, I wasn't only referring to such issues when I said that I had awkward conversations with colleagues about our PNAS paper. Rather, there is a long – and mostly honourable – tradition in linguistics since the work of Franz Boas to assume that there are no "primitive" languages and that all languages are suited to the needs of the communities that use them; this point of view has been reinforced by Chomskyan ideas of Universal Grammar. So a lot of the objections to the idea of potential genetic effects on language (like the objections to the idea that /f/ sounds are more available given modern dentition) are based on ideas about What Language Is Like, not anything that can be caricatured as a product of "the PC brigade".

jin defang said,

December 23, 2020 @ 10:43 am

Apologies for being dense, but how could a connection between tonal languages and alleles be used to justify the superiority of one group over another?

[(myl) The problem starts with a couple of false ideas: that human genetic variation determines a dominant fraction of human life outcomes in modern societies; and that socially-defined ethnic, racial and gender categories correspond to large, consistent, and behaviorally-relevant genetic differences across a wide range of aptitudes. People use arguments of this kind to justify all sorts of racist, sexist, and classist prejudices, seen most clearly in the ideologies of Nazi Germany, but common elsewhere as well.

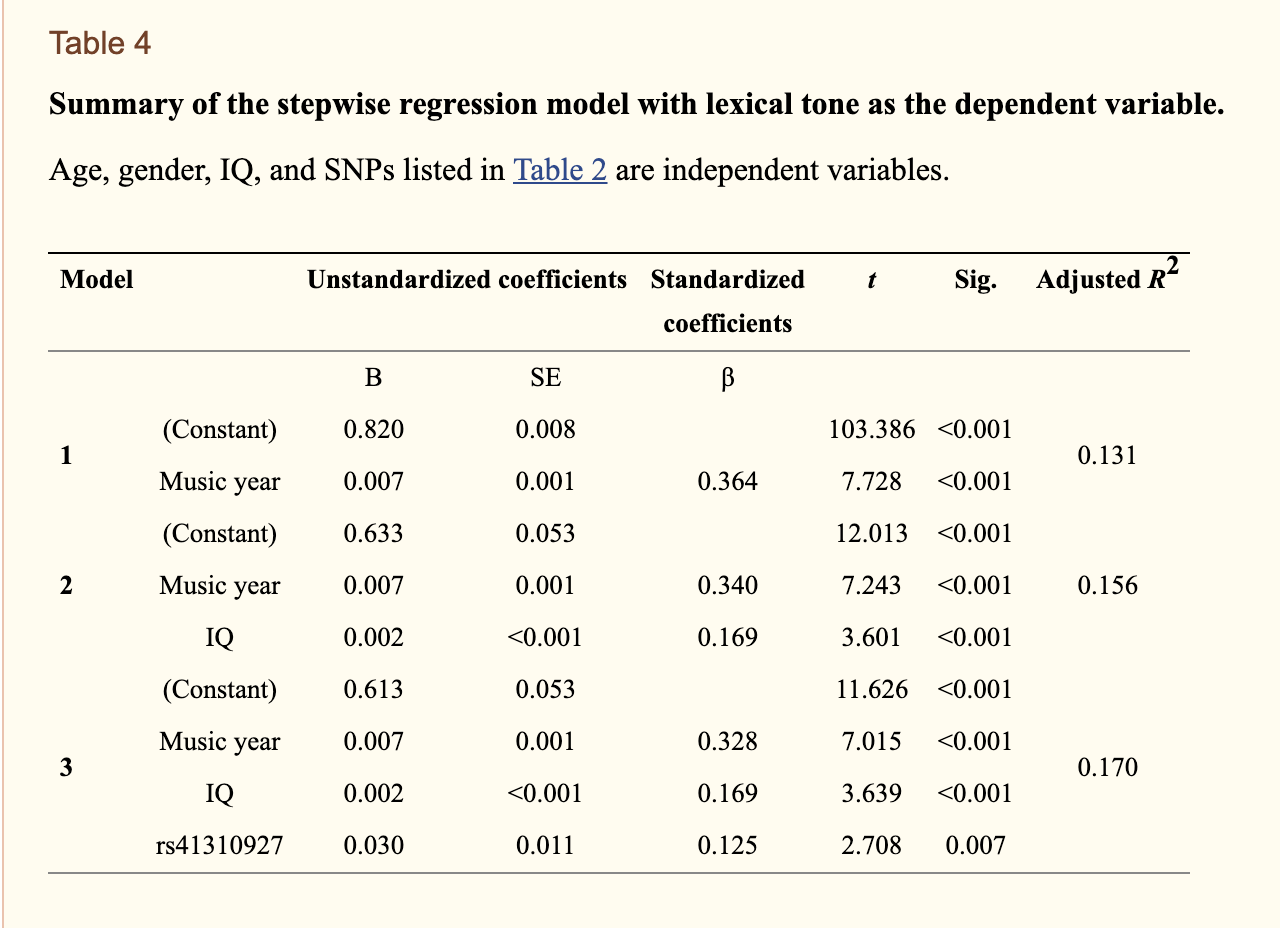

I added Figure 1 from Wong et al. 2020 to Bob's post, in anticipation of a reaction like Philip Taylor's. You can see there (in Figure 1A) that SNP rs41319827 does predict tone perception, which supports the Dediu & Ladd hypothesis — but there's a LOT of variation in performance within each SNP-defined category — and Figure 1B shows that IQ+Musical Training is even more predictive. If you look at their Table 4

you'll see that years of musical training is the most predictive single feature.

It's also true, as Philip Taylor suggests, that the potential for toxic mis-application leads some people to reject all investigations of connections between genetic and behavioral variation. It's wrong, of course, to see see a choice between "Genes explain everything" and "Genes explain nothing". But the known facts — that any group has large within-group variation in both genotype and phenotype, and that genes interact in complex non-linear networks with each other and with environmental factors — should pre-dispose us to being skeptical of "because genes" arguments, especially if the explicandum is something of socio-economic value.]

Philip Taylor said,

December 23, 2020 @ 10:55 am

Fair enough, Bob — I would not seek for one second to suggest that research findings, in the wrong hands, cannot be abused in order to suggest that they support any otherwise untenable position. But I think that you will also agree that when Hans Eysenck, for example, suggested that "neurotic predisposition is to a large extent hereditarily determined", he did so at a time when such suggestions were scientifically acceptable; if his son, Michael Eysenck, were to seek to make such a suggestion today, he would be very lucky if any reputable journal would touch his paper with a barge-pole. Thus there are times when it is safe, and acceptable, to make claims concerning genetics, and there are times (such as today) where any such claims would be perceived as borderline (if not full-on) racist. That is the only point I was seeking to make.

P.S. Sorry for the horrible forced line-breaks in the preceding — I passed the text and markup through JSBIN to check that it would render OK, and forgot that introducing line breaks would not affect the JSBIN rendering but would affect the LL version.

Victor Mair said,

December 23, 2020 @ 11:36 am

Tones arise (tonogenesis), merge, and disappear synchronically and diachronically, as in Vietnamese, Tibetan, Sinitic, and Lithuanian. Does that mean that the genetic makeup of individuals and groups transforms as these changes occur?

[(myl) Obviously the Dediu-Ladd hypothesis is that this genetic difference nudges (non-)tonogenesis, as a result of a small difference in the relative salience of (certain aspect of) pitch perception — not that it determines it.]

As for ASPM, with which many readers may not be familiar, here are the opening paragraphs of the Wikipedia article about it:

=====

Abnormal spindle-like microcephaly-associated protein also known as abnormal spindle protein homolog or Asp homolog is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ASPM gene. ASPM is located on chromosome 1, band q31 (1q31). The ASPM gene contains 28 exons and codes for a 3477 amino‐acid‐long protein. The ASPM protein is conserved across species including human, mouse, Drosophila, and C. elegans. Defective forms of the ASPM gene are associated with autosomal recessive primary microcephaly.

"ASPM" is an acronym for "Abnormal Spindle-like, Microcephaly-associated", which reflects its being an ortholog to the Drosophila melanogaster "abnormal spindle" (asp) gene. The expressed protein product of the asp gene is essential for normal mitotic spindle function in embryonic neuroblasts and regulation of neurogenesis.

A new allele of ASPM arose sometime in the past 14,000 years (mean estimate 5,800 years), during the Holocene, it seems to have swept through much of the European and Middle-Eastern population. Although the new allele is evidently beneficial, researchers do not know what it does.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ASPM_(gene)

=====

Chris Button said,

December 23, 2020 @ 12:01 pm

Interesting stuff. I haven't read any of the background materials, but I'm somewhat skeptical based on what's included in this post. There are few reasons:

1. Following on from Victor Mair's point, surely the segmental origin of suprasegmental tones throws in a little wrench?

2. We all speak tone languages. It's just when tone is used lexically that languages are conventionally termed "tone languages". So are we talking about how tone is used in the lexicon rather than tone per se?

3. Some areas of the world have a preponderance of pitch tone languages. Others have a preponderance of contour tone languages. Can we make similar statements about the pitch versus contour distinction?

4. Related and unrelated Languages in close proximity tend to borrow features of each others languages. Wouldn't that be a simple explanation for the statistical correlations?

Apologies in advance if some of these questions are covered in the supplementary readings.

[(myl) In all languages, including English, consonant manner distinctions have large F0 effects (see "Consonant effects on F0 of following vowels", 6/5/2014). In some languages (Chinese, Vietnamese, Thai, Korean, …) these have been historically re-analyzed to one extent or another as tonal effects on neighboring vowels; and in other languages, (English, French, German, Russian, Arabic, …) phonetic effects of comparable size have not been so re-analyzed. There are pretty clear areal influences — obviously this kind of sprachbund is well attested in other cases, so we don't need a genetic nudge. But equally obviously, a genetic nudge might help it along.

This argument tells us nothing, though, about the many tonal languages in other parts of the world (e.g. sub-Saharan Africa) where tonogenesis from consonant manner is not suggested by anything that we know about the history.]

Chris Button said,

December 23, 2020 @ 12:18 pm

If that were the case then why would tonal distinctions ever collapse/converge across related languages (unless the distinctions they were making had become utterly redundant).

Furthermore, pitch/contour often correlate with things like breathy or creaky voice. Those have a lot to do with the diachronic emergence and synchronic realization of tones, but are not tones themselves (or are they? e.g. Burmese creaky tone).

J.W. Brewer said,

December 23, 2020 @ 12:27 pm

Those of us who don't speak languages with lexical tone but who are interested in languages have often seen supposed examples of comical misunderstandings that can result when two words or phrases disambiguated only by tone have different meanings that make one word-or-phrase highly incongruous in a context where the other is perfectly appropriate. So what we need now is an evolutionary biology Just So Story about how increased/reduced ability to avoid those comical misunderstandings drives increased/decreased reproductive success.

rpsms said,

December 23, 2020 @ 12:34 pm

I have a very limited understanding, but in e.g. Mandarin "Hip-Hop" (rap) and Rock, tone (lexical?) is not "respected" but does not seem to get in the way or otherwise destroy the meaning. Coupled with the fact that in many studies of "perfect pitch", many or most children seem to exhibit near perfect pitch but non-tonal language speakers seem to lose it after early infancy, and you wind up wondering what order of magnitude of impact such a genetic correlation could have that isn't simply dwarfed by cultural context.

J.W. Brewer said,

December 23, 2020 @ 12:41 pm

A different take on the Boasian point is the assumption that any human infant (absent some sort of physiological/neurological impairment) regardless of ancestry/genes can learn any extant human language equally well if raised in a community that speaks it. We certainly have evidence of that with respect to a limited number of languages that due to historical happenstance have ended up being the L1's of an extremely racially/ethnically/genetically varied set of native speakers, such as English/French/Spanish/etc. But we have a limited sample size. So we may assume (because of these Boasian assumed axioms we were generally exposed to in an intro undergrad linguistics survey) that if e.g. history had worked out such that speakers of a Khoisan click language had become a worldwide imperial power and caused assimilation to their language of a very genetically diverse range of colonial subjects, immigrants, etc., then it would turn out that humans of any sort of genetic background can manage a click language as well as any other. But that remains an assumption that ought to in principle be falsifiable by contrary evidence.

[(myl) The obvious fact that you cite — any infant can learn any language — obviously falsifies the idea that some linguistic features (like tone) are genetically determined. But it leaves open the possibility that there are some genetically-influenced differences in perceptual salience or production facility that nudge historical development in one direction or another.]

Andreas Johansson said,

December 23, 2020 @ 1:27 pm

Is there any known advantage to having the new variant of the gene? Difficulty distinguishing tones is presumably a disadvantage irrespective of whether you speak a tone language.

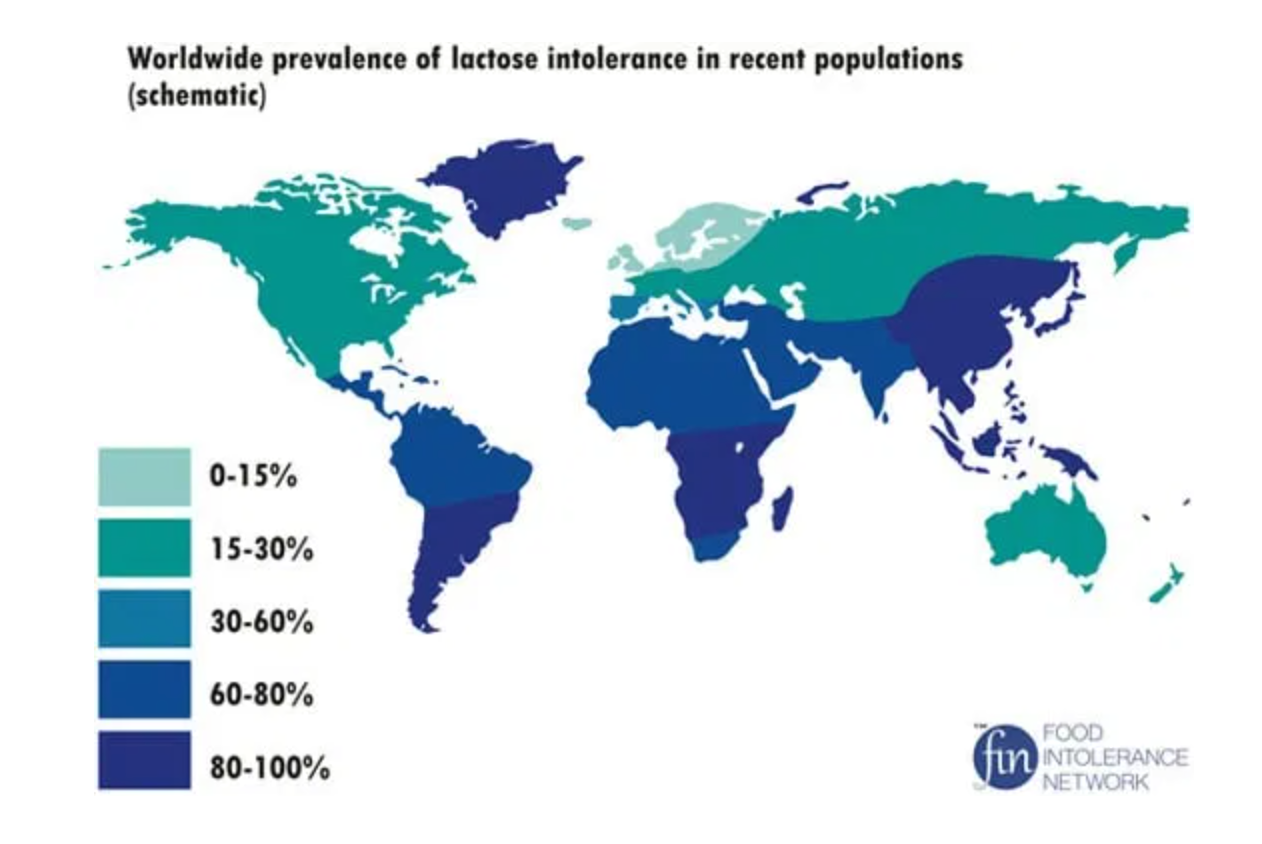

[(myl) If there is an advantage, I haven't been able to find it. I gather that this sort of thing can be a random consequence of drift in a small founder population. But who knows, maybe it's pleiotropically connected to some kind of cultural innovation, like digesting gluten or lactose (which has a suspiciously similar geography)…

(though the genetic basis of lactose tolerance is known and different).]

Chris Button said,

December 23, 2020 @ 3:33 pm

Sure, but my point #1 was actually about when phonological segments disappear entirely to leave tonal reflexes (i.e., not just about how the manner of articulation can influence tone contours across the syllable). For example, /s/ debuccalization is known in Spanish and Chinese. Can we really put the fact that this earlier syllable final -s has ended up as a tonal distinction in Chinese–but not in Spanish–down to genetics? When did the genetic influences start kicking in? And why only then?

Y said,

December 23, 2020 @ 3:51 pm

Wong et al.'s study is good because it eliminates so many of the non-biological variables which, to my mind, made the Dediu-Ladd paper unconvincing. Now comes the question, was the performance test germane to the question of tone languages? In the test, "participants were asked to judge in each [nonsense, pseud0-Cantonese] three-syllable trial whether the tone of the last syllable was the same as the first or the second syllable." … "Chance performance level was 50%." The supplementary materials provide a histogram (fig. S1, p. 13) of the test scores, showing a peak near 1, dropping steadily off to 0.5. Now, are those, say, 10% of speakers who scored below 0.75 truly inhibited in their perception of Cantonese? Or is this particular test more of a "parlor trick", which might be linked to a particular genotype, but not to correct language transmission? Put another way: there are language learners whose production is clearly affected by their limited perception, say L1 learners who can't hear high frequencies and don't produce fricatives correctly; or adult L2 English learners who don't learn to distinguish /ɪ/ and /i/ and so don't produce them correctly. With this much genetic variation among Cantonese speakers, wouldn't you expect a significant number of Cantonese speakers to misunderstand words based on misperceived tone, or to take longer to learn tones as children? Are the few subjects who scored nearest 0.5 in the test truly bad at understanding tones in their language?

Bob Ladd said,

December 23, 2020 @ 4:46 pm

@Chris Button: All good questions, and yes, some of them are answered (at least implicitly) in the linked PsyArXiv paper. But the key point that many people miss is that we are obviously not talking about effects on the individual level. If there is some sort of individual predisposition for or against tone languages, it is not going to affect an individual's language directly, because (as J W Brewer said and as everyone knows), any child without obvious anatomical or neurological impairments will learn whatever language(s) they are exposed to from birth. But we also know that language is always changing, and if enough speakers have a predisposition one way or another it may steer language change in one direction or another. That is the basic suggestion.

The definition of "tone language" is obviously an issue. If pitch perception is somehow affected by ASPM, the relevant difference between "tone languages" and "intonation languages" might be a matter of how easy it is to tune into pitch on (more or less) every syllable rather than the essentially grammatical fact that pitch is being used in the lexicon. In European languages generally, you only have to tune into the pitch every so often.

Y said,

December 23, 2020 @ 7:45 pm

Nan et al., Congenital amusia in speakers of a tone language: association with lexical tone agnosia (Brain 133, 2635, 2010) find that Mandarin speakers with lexical tone agnosia, i.e. clearly lower recognition of tones in isolated word tests, nevertheless produced tones nearly as perfectly as control subjects. That implies that even a high percentage of lexical tone agnosics within a population would not push a language toward losing lexical tone. If the effects observed by Wong et al. are comparable, I don't see how they (and therefore the genes under discussion) could be linked to tone languages losing lexical tone.

There's the separate question of whether some physiological tendency could encourage a language to develop lexical tone, but I don't see how Wong et al.'s study can address that.

Bob Ladd said,

December 24, 2020 @ 1:52 am

@Y: Your two comments get right to the heart of the issue here. In a sense, yes, the test that Wong et al got their Cantonese speakers to do was a kind of parlor trick, which doesn't seem to have any relation to their ability to function in Cantonese. But what that tells us is that beneath the apparently uniform description "native speaker of Cantonese" there's a lot of individual variation. The thinking behind the Dediu/Ladd study is that if different speech communities have different group-level PATTERNS of individual differences, those differences could, over time, lead to changes in the language of the different communities. As we discuss in the linked PsyArXiv paper, this idea has been around at least since the 1950s and there is some evidence from lab experiments with artificial languages that the direction of language change can be affected in this way.

That still doesn't tell us what the brain-level effect of having different variants of ASPM is, or why the new variant seems to have spread fairly rapidly in Europe and parts of Asia, but Wong et al.'s demonstration that the new variant makes it harder for people to do this particular parlor trick accurately makes it more plausible that the geographical correlation documented by Dediu and Ladd does – somehow – reflect some kind of causation.

Kaleberg said,

December 26, 2020 @ 10:18 pm

There's also a strong correlation with latitude. Could tonality have something to do with more consistent insolation?

I can't rule out genetics, but language families tend to spread in geographical regions, and they tend to preserve a variety of properties including tonality. Two of those clusters are almost certainly Indo-European and Bantu, and I'm willing to bet there is a group including Tai in southeast Asia.

Chris Button said,

December 29, 2020 @ 9:42 am

@ Bob Ladd

Off topic, but presumably you're the same Bob Ladd who had a letter to the editor in the Economist last week? I figure there can't be that many people with the same name who are equally versed in lingusitic issues pertaining to Latin.

Alexander Pruss said,

December 29, 2020 @ 11:58 am

@Andreas Johansson: Intuitively, insensitivity to lexically irrelevant features could be a plus. If two people pronounce a word with different tone, and you are really good at distinguishing tone, couldn't it be slightly harder to tell that it's the same word?

I remember once seeing one of those numeral-hidden-in-dots pictures that are used for colorblindness screening but in this case it was the trichromats who were supposed to have a harder time seeing the numeral. I think it was supposed to work because for trichromats the color differences between the dots swamped the subtler luminance differences that the colorblind picked up.