Trends

« previous post | next post »

About six weeks from now, I'm scheduled to give a (virtual) talk with the (provisional) title "Historical trends in English sentence length and syntactic complexity". The (provisional) abstract:

It's easy to perceive clear historical trends in the length of sentences and the depth of clausal embedding in published English text. And those perceptions can easily be verified quantitatively. Or can they? Perhaps the title should be "Historical trends in English punctuation practices", or "Historical trends in English conjunctions and discourse markers." The answer depends on several prior questions: What is a sentence? What is the boundary between syntactic structure and discourse structure? How is message structure encoded in speech (spontaneous or rehearsed) versus in text? This presentation will survey the issues, look at some data, and suggest some answers — or at least some fruitful directions for future work.

So I've started the "look at some data" part, so far mostly by extending some of the many relevant earlier LLOG Breakfast Experiment™ explorations, such as "Inaugural embedding", 9/9/2005, or "Real trends in word and sentence length", 10/31/2011, or "More Flesch-Kincaid grade-level nonsense", 10/23/2015.

In most cases, the extensions just provide more data to support the ideas in the earlier posts. But sometimes, further investigation turns up some twists.

For example, in "Death before syntax?", 10/20/2014, I quoted from Ursula K. Le Guin's essay "Introducing Myself", (as published in The Wave in the Mind, 2004). Here's the passage I quoted, and a bit more besides:

What it comes down to, I guess, is that I am just not manly. Like Ernest Hemingway was manly. The beard and the guns and the wives and the little short sentences. I do try. I have this sort of beardoid thing that keeps trying to grow, nine or ten hairs on my chin, sometimes even more; but what do I do with the hairs? I tweak them out. Would a man do that? Men don’t tweak. Men shave. Anyhow white men shave, being hairy, and I have even less choice about being white or not than I do about being a man or not. I am white whether I like being white or not. The doctors can do nothing for me. But I do my best not to be white, I guess, under the circumstances, since I don’t shave. I tweak. But it doesn’t mean anything because I don’t really have a real beard that amounts to anything. And I don’t have a gun and I don’t have even one wife and my sentences tend to go on and on and on, with all this syntax in them. Ernest Hemingway would have died rather than have syntax. Or semicolons. I use a whole lot of half-assed semicolons; there was one of them just now; that was a semicolon after “semicolons,” and another one after “now.”

And another thing. Ernest Hemingway would have died rather than get old. And he did. He shot himself. A short sentence. Anything rather than a long sentence, a life sentence. Death sentences are short and very, very manly. Life sentences aren’t. They go on and on, all full of syntax and qualifying clauses and confusing references and getting old. And that brings up the real proof of what a mess I have made of being a man: I am not even young. Just about the time they finally started inventing women, I started getting old. And I went right on doing it. Shamelessly. I have allowed myself to get old and haven’t done one single thing about it, with a gun or anything.

And in that post, I used some short samples from Le Guin and from Hemingway to suggest that their styles were less different than she suggests, at least in terms of superficial features like sentence length and semicolon usage. (Of course, her essay is not really about prose style, but never mind that for now…)

So this morning, I compared those superficial features on a larger sample — all of Le Guin's essay collection The Wave in the Mind, and all of Hemingway's 1964 memoir A Moveable Feast. At that scale, Le Guin is right about semicolon usage rates for her vs. Hemingway:

| Source | Semicolons | Total Characters | Semicolons per 100k Characters |

| The Wave in the Mind | 411 | 520,607 | 78.95 |

| A Moveable Feast | 58 | 319654 | 18.14 |

But it probably won't surprise you to learn that gender is not a good predictor of semicolon usage rate. There's a general historical tendency towards decreased rates, but if there's a correlation with gender, it's going to be fairly small and we'll need quite a bit of data to determine whether it even exists:

| Source | Date | Semicolons | Total Chars | Semicolons/100k Chars |

| Pamela | 1740 | 4,676 | 1,126,913 | 414.94 |

| Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire | 1788 | 39907 | 12936452 | 308.48 |

| Camilla | 1796 | 5,786 | 1,975,887 | 292.83 |

| Pride and Prejudice | 1813 | 1538 | 680359 | 226.06 |

| American Notes | 1842 | 1464 | 579209 | 252.76 |

| Little Men | 1871 | 925 | 548,683 | 168.59 |

| Middlemarch | 1872 | 1,874 | 1,761,476 | 106.39 |

| Tom Sawyer | 1876 | 642 | 379,164 | 169.32 |

| The River War | 1899 | 629 | 738,261 | 85.20 |

| The Wonderful Wizard of Oz | 1900 | 194 | 202966 | 95.58 |

| The Great Gatsby | 1925 | 60 | 162,323 | 22.87 |

| To the Lighthouse | 1927 | 941 | 381,272 | 246.81 |

| Murder Must Advertise | 1933 | 241 | 639,852 | 37.66 |

| Murder on the Orient Express | 1934 | 20 | 338,879 | 5.90 |

| V. | 1963 | 761 | 1,028,507 | 73.99 |

| A Moveable Feast | 1964 | 58 | 319,654 | 18.14 |

| Oryx and Crake | 2003 | 362 | 597,829 | 60.55 |

| The Wave in the Mind | 2004 | 411 | 520,607 | 78.95 |

(Titles in red have female authors; those in blue have male authors. Editorial as well as authorial fashions have probably played a role in the history. And my versions of the texts have various sources and in some cases different formatting styles, but the counts and relative frequencies would not be changed much by regularization.)

There are hundreds more texts and numbers, which I'll spare you for now.

One relevant point, though, is that semicolons are not very "syntactic". Rather, they're usually rather paratactic. Semicolons can concatenate a sequence of sentences that might very well be separated by periods; they can mark the junctures of a series of conjoined phrases; and they can set off appositive phrases. Le Guin's example is the sentence-concatenating kind:

I use a whole lot of half-assed semicolons;

there was one of them just now;

that was a semicolon after “semicolons,” and another one after “now.”

Virginia Woolf's To the Lighthouse stands out in the table above as especially semicolonic for its date of publication — and the examples in that novel are in most cases also paratactic. Here are the first two semicolonized sentences:

Such were the extremes of emotion that Mr. Ramsay excited in his children's breasts by his mere presence; standing, as now, lean as a knife, narrow as the blade of one, grinning sarcastically, not only with the pleasure of disillusioning his son and casting ridicule upon his wife, who was ten thousand times better in every way than he was (James thought), but also with some secret conceit at his own accuracy of judgement.

He was incapable of untruth; never tampered with a fact; never altered a disagreeable word to suit the pleasure or convenience of any mortal being, least of all of his own children, who, sprung from his loins, should be aware from childhood that life is difficult; facts uncompromising; and the passage to that fabled land where our brightest hopes are extinguished, our frail barks founder in darkness (here Mr. Ramsay would straighten his back and narrow his little blue eyes upon the horizon), one that needs, above all, courage, truth, and the power to endure.

Here's an example from Letter I in Pamela:

God bless him! and pray with me, my dear father and mother, for a blessing upon him, for he has given mourning and a year's wages to all my lady's servants; and I having no wages as yet, my lady having said she should do for me as I deserved, ordered the housekeeper to give me mourning with the rest; and gave me with his own hand four golden guineas, and some silver, which were in my old lady's pocket when she died; and said, if I was a good girl, and faithful and diligent, he would be a friend to me, for his mother's sake.

That style certainly makes for long sentences, but the resulting depth of embedding is not generally very great. (Though the syntactic treatment of discourse-structure relations is a wild card here, as always — see e.g. "Parataxis in Pirahã", 5/19/2006.)

And for another (more offensively stereotyped) take on the gender associations of semicolons, there's Kurt Vonnegut in A Man Within a Country:

Here is a lesson in creative writing. First rule: Do not use semicolons. They are transvestite hermaphrodites representing absolutely nothing. All they do is show you've been to college.

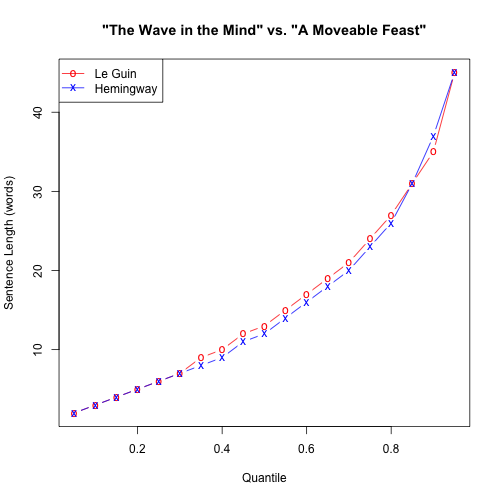

How about Le Guin's joking references to sentence length? In The Wave in the Mind, the mean sentence length is 17.18 words, and the median is 13 words. In Hemingway's A Moveable Feast, the mean sentence length is 16.78 words, and the median is 12 words. A plot of sentence-length quantiles in the two books shows remarkable agreement throughout:

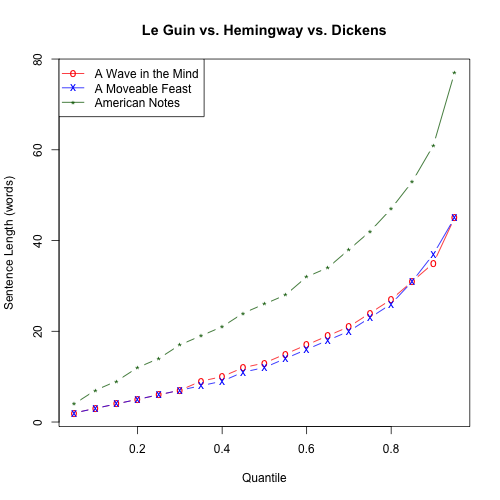

Just to show that things can be sometimes be different, let's add Charles Dickens' American Notes to the plot:

That's all I have time for today, but (some of) the loose ends will be followed later…

AntC said,

March 27, 2022 @ 10:23 pm

That's all I have time for today,

Sheesh Mark, thank you! All you have time for before breakfast is more than an ordinary mortal could assemble in a month.

Yes To the Lighthouse's semicolon rate stands out. I always thought that what marks out stream of consciousness style is the absence of full stops/periods. Everything crowding into the mind at the same time/in no particular sequence, 'innit. Whether the author uses commas vs semicolons seems not very consistent/perhaps depends more on the publisher/sub-editor?

For those two paragraphs you quote, I think the sense wouldn't change if that were all commas/no semicolons. Whereas making it all full stops would interrupt the 'flow'.

For comparison I looked at Ulysses. There's a plethora of commas in places other authors might put more full stops; there's scant semicolons. But it varies hugely across different passages; as does the length of paragraphs. Joyce is using typography cryptographically, you might say.

the resulting depth of embedding is not generally very great.

Yes this. To measure computational complexity we distinguish embedding vs iteration. Embedding means there's a discontinuous 'outer' structure, whose right-hand tree must correlate across the embedded structure. (That Pirahã does not have, reportedly.) Needs holding a context across the parse. Iteration means the outer structure is finished before starting the parse of the inner/there's only a conjunction to flag the start.

Isn't that a pervasive effect? For example 'heavy' NPs that should be embedded in phrasal verbs get pushed to the end of a sentence, where they can get processed as iterations.

AntC said,

March 28, 2022 @ 12:03 am

we distinguish embedding vs iteration.

By "we", I mean in specifying programming languages: a recursive grammar does specify iteration/repetition by the same means as embedding. But it's commonplace to adopt notational conventions such as these — which make for easier computation by shift-reduce parsers, and make it easier for humans to follow.

Marianne Hundt said,

March 28, 2022 @ 1:32 am

Punctuation isn't as directly linked to grammatical change in English as one might think. With some developments, there seems to be a split development of punctuation rules in writing and grammatical changes, e.g. with focaliser constructions (https://doi.org/10.1075/slcs.221.06hun – p. 213) but also with relative clauses (DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1360674312000032 – p. 2019 for a table that shows development of punctuation in scientific discourse in ARCHER).

DDeden said,

March 28, 2022 @ 7:22 am

Useless aside: "innit" seems to be commonly used in European English, I almost never heard it in midwest US, but when I went to Malaysia & Singapore all I heard was "izzit?"; apparently they both mean "is it not it?".

Terry Hunt said,

March 28, 2022 @ 9:27 am

@ DDeden – "innit" is a contraction of "isn't it?" and "izzit? of "is it (not)?"

"Innit?" is/was one element of a characteristically London (even Cockney) speech pattern wherein the speaker ends a declarative sentence with a rhetorical question, as if to elicit the listener's aggreement:

"I did this, di'n I?" You say this, don'cher? "This is such, innit?" "We did that, din' we?" etc., etc. This pattern was common up to my parents' (born late 1930s) generation, and I sometimes assume it deliberately to jestingly irritate my contemporary but non-Londoner friends.

In more recent generations, the single term "innit?" seems to have initially been selected by first or second-generation immigrants to Britain (particularly to the London area) for use in all such rhetorical statement endings regardless of theoretically appropriate grammar (as exemplified by the comedian Harry Enfield's 1980s Greek character Stavros). From them it has, I gather, spread into the general London 'street dialect' spoken by most teenagers amongst themselves in public, regardless of their normal class registers and regional dialects, and presumably further picked up by others learning English as a second language by example rather than from formal instruction.

I don't remember "izzit?" it from Singapore, but I only spent a year there aged 7, when it had perhaps not yet entered Singlish, and where in any case I mostly spoke with other temporary expats rather than with native Singaporeans.

Philip Taylor said,

March 28, 2022 @ 10:02 am

Terry — how would one know whether a speaker had said "izzit" or "is it" ? Are they not pronounced identically, unlike "innit" which is markedly different from "isn't it" ?

Barbara Phillips Long said,

March 28, 2022 @ 2:29 pm

I was paging through Georgette Heyer’s Venetia recently after reading about the release of a Folio Society edition of the novel. I noticed there were more semicolons than I see in my other reading. I also noticed more use of colons.

[(myl) At least in this version, the semicolon frequency is moderate:

362 semicolons in 673131 characters: 53.78 per 100k

But maybe there's something about the usage patterns that makes the semicolons salient. Here are the first couple of semicolonized sentences:

When he walked it was with a pronounced and ugly limp; and although the disease was said to have been arrested the joint still pained him in inclement weather, or when he had over-exerted himself.

By the time he was fourteen if he had not outstripped his tutor in learning he had done so in understanding; and it was recognized by that worthy man that more advanced coaching than he felt himself able to supply was needed.

In those sentences (and in a few more encountered in skimming the text), there are some places where I would have expected commas; and as a result, have to work a bit harder to take the phrases in.]

Jerry Packard said,

March 28, 2022 @ 3:45 pm

Wow, interesting.

Julian said,

March 28, 2022 @ 5:34 pm

Looking forward to next instalment on how you would answer 'What is a sentence?'

It's a key threshold question for any grammar book, and bad popular grammar books are usually terrible at answering it ('a sentence expresses a complete idea… a sentence ends with a full stop…')

How many sentences are there in the written string 'Read. My. Lips.'?

AntC said,

March 28, 2022 @ 5:49 pm

Useless aside: "innit" seems to be commonly used in European English, …; apparently they both mean "is it not it?".

Useless continuation: I'm pretty sure all varieties of English include tag questions — and that ref talks of "most languages", n'est-ce pas.

"the tendency is to have a negative tag after a positive sentence and vice versa, but unbalanced tags are also possible."

I'm not sure I fit into any of @Terry's categories. Usage of 'innit' might have waxed and waned a bit, but it's never disappeared AFAICT. I'm a Londoner, emigrated (to Yorkshire) 1970's. I probably picked it up from the steam radio: The Goons/Pete'n'Dud/Kenneth Williams' funny voices. I would have adopted it as a revolting teenager, to annoy my parents.

Bloix said,

March 29, 2022 @ 8:44 am

From Beatrix Potter's The Tailor of Gloucester, her lovely Christmas story. Four sentences, three semicolons and one dash:

When the snow-flakes came down against the small leaded window-panes and shut out the light, the tailor had done his day's work; all the silk and satin lay cut out upon the table.

There were twelve pieces for the coat and four pieces for the waistcoat; and there were pocket flaps and cuffs, and buttons all in order. For the lining of the coat there was fine yellow taffeta; and for the button-holes of the waistcoat, there was cherry-coloured twist. And everything was ready to sew together in the morning, all measured and sufficient—except that there was wanting just one single skein of cherry-coloured twisted silk.

Barbara Phillips Long said,

March 29, 2022 @ 6:26 pm

Re Venetia (2011 trade paperback edition by Sourcebooks, Inc.)

One specific area I looked at in Venetia was the beginning of Chapter 13 (about the first quarter of the chapter). There were a number of sentences that used semicolons. Some sentences used colons when dialogue came later in the sentence, although Heyer uses colons at other times, too.

In the dialogue with Mrs. Scorrier, there are no semicolons in the dialogue itself, although there are en dashes. Heyer, or Heyer’s editors, do not appear to use dashes in places where current prose style would.

My reaction to the way semicolons are deployed in Venetia is that Heyer uses them to link sentences in a paragraph to form a substructure or grouping of items she considers more closely related to each other than the other sentences in the paragraph. The examples quoted above from the beginning of Venetia show this approach.

Heyer also uses semicolons when she is making lists and there are commas within some of phrases in the lists. Iterative use is a long-standing use of semicolons, and Heyer’s use of semicolons in iterations feels different to me than the groupings, in that semicolons in iterations seem more like a mechanical use of punctuation rather than a desire to link more closely some parts within a paragraph.

Terry Hunt said,

March 30, 2022 @ 1:21 pm

@ Philip Taylor — Primarily I was answering DDeden in the same terms as he had used, but I think that "izzit?" is generally spoken slightly more tersely (if that makes sense) than "is it?" and with slightly less (or no) terminal uplift. However, my experience of it is limited: others may have better insight (insound?)

Terry Hunt said,

March 30, 2022 @ 1:35 pm

@ AntC — I agree that "innit?" has endured; my point was that it has not only persisted where grammatically appropriate, but has largely replaced all the other grammatical forms of the Cockney tag question. Thus instead of saying "It makes me mad, dunnit?", a modern yoof will say "It makes me mad, innit?" Or so I understand: I haven't really conversed with anyone much younger than me in a casual register for a couple of decades, and (as a resident of southern Hampshire) have rarely visited London at all in the same period, thought that may change in future if my father completes his intended relocation to the environs of Chelsea.

Philip Taylor said,

March 30, 2022 @ 2:32 pm

Terry — in that case, I don't think that I have encounted "izzit" in the wild. But as regards terminal uplift, in my idiolect this would be completely absent in the negative emphatic phrase "Is it hell ?!" (where "hell" can, of course, be replaced with both less and more coarse words).