Mandarin morphosyllabic annotation of a Taiwanese sign

« previous post | next post »

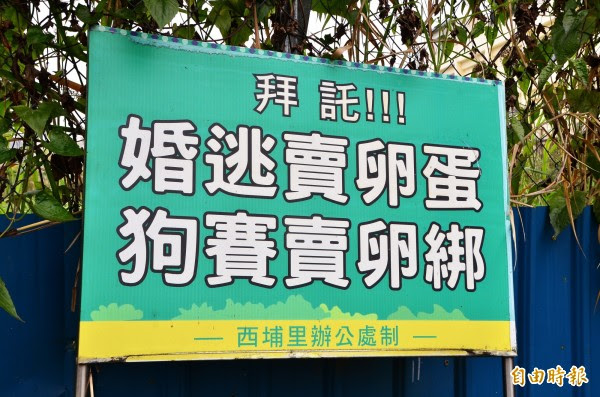

Public notice in a ward in Tainan, Taiwan:

(Source)

If you read the sign character by character in Mandarin, it makes no sense:

hūn táo mài luǎn dàn

gǒu sài mài luǎn bǎng

婚逃賣卵蛋

狗賽賣卵綁

marriage escape sell roe egg

dog race sell roe bind

However, if you pronounce the characters with their Mandarin sounds but understand those sounds with their Taiwanese meanings, it makes perfect sense, as Chau Wu explains:

First line:

婚 MSM hun 'marriage' > Tw hun 燻 'fume' (Sp. fumar 'to smoke') > Tw. hun cigarette. (Note: Tw does not have the -um sound, all European -um words are converted to -un.)

逃 MSM (pinyin taó) tháu 'escape' > Tw thâu 頭 'head'

So, 婚逃 > 燻頭 'cigarette butt'.

賣 MSM mài 'sell' > Tw mài (crasis of m̄ and ài) 呣愛 'do not'.

卵 MSM luăn 'roe' > Tw loān 亂 'wrong, wrongly'.

蛋 MSM (pinyin dàn) tàn 'egg' > Tw tàn 擲 'throw'.

Therefore, 卵蛋 > 亂擲 'throw randomly/all over the place'

So, the first line, when read in Tw with MSM pronunciation, means 'Do not throw cigarette butts all over the place.'

Second line: Similar construction, two words need explanation.

賽 MSM sài 'competition, race' > Tw sài 屎 'feces'.

So, 狗賽 > 狗屎 dog's feces.

綁 MSM băng 'to bind' > Tw pàng 放 [大便].

So, the second line means 'Do not let dogs defecate all over the place.'

Now, why do you think the people who wrote this sign would go to all those contortions to say something so straightforward and simple?

Readings

"No shitting here" (10/10/15)

"Scoop the poop" (4/15/15)

"Ruby phonetic annotation for Cantonese" (5/6/19)

"Phonetic annotations as a welcome aid for learning how to read and write Sinographs" (4/26/19) — with dozens of additional posts on the value of phonetic annotation listed in the "Readings" section at the end

Mark Hansell said,

May 13, 2019 @ 9:06 am

I doubt that Taiwanese hun ('smoke') is related to Spanish, it seems like a perfectly reasonable cognate of Mandarin xun, but that doesn't matter to the main point, which is the (almost) purely phonographic use of hanzi.

What this most reminds me of is Japanese Manyogana, the earliest writing of native Japanese words. After Chinese writing arrived in Japan, it was still used mainly to write the Chinese language. When people started trying to accurately represent the Japanese language, they used some characters semantically (that is, to represent a given Japanese word, used the hanzi that corresponded to a Chinese word of the same meaning), and some phonetically (to represent a Japanese word, strung together characters whose Chinese pronunciation corresponded to the Japanese syllables of the word, ignoring the original meaning of the hanzi.)

Same thing here– 狗 is used semantically, in that it represents the same meaning in Mandarin as Taiwanese, but the pronunciation is different. (高 gāo in Mandarin is a closer approximation to the sound of 'dog' in Taiwanese.) For all the other hanzi on the sign, the phonographic strategy is used, with the Mandarin pronunciation of each hanzi providing (an approximation of) the sound of the Taiwanese word.

Of course it is unlikely that Taiwanese will ultimately go the route that Japanese followed– with the phonographically used hanzi being graphically simplified and organized into a syllabic (actually moraic, but 差不多) writing system, modern hiragana and katakana– but this is a beautiful illustration of the fact that people all over, in all different historical eras, apply the same kind of practical problem solving to the difficulties of representing language visually.

WSM said,

May 13, 2019 @ 9:17 am

I'm also skeptical of Min 燻/xun/hun being related to fumar absent more evidence. What's strange here is that there are generally accepted orthographies for many of these usages, such as 薰頭 for hun tao.

I've always wondered whether "mai" in Min (and perhaps other southern dialects) is related to classical 莫 (Mandarin mo, also "do not").

ouen said,

May 13, 2019 @ 12:20 pm

Writing the message this way sounds less like an order from up high than it would to write it in mandarin?

Nothing but a change of tone in my opinion. But I’m not certain why.

I certainly don’t think there are monolingual Taiwanese speakers who can be reached by this sign but would not understand a sign in mandarin. Understanding this sign requires competence in both mandarin and Taiwanese,

Ouen said,

May 13, 2019 @ 12:21 pm

Oh it’s done for the sake of humour, that’s the consensus of the Taiwanese internet

Victor Mair said,

May 13, 2019 @ 1:43 pm

I think there are deeper, more fundamental reasons.

krogerfoot said,

May 13, 2019 @ 5:37 pm

The first thing I thought of was how, in Japan, you sometimes see warnings about various unsavory behavior written prominently in the languages of the foreigners thought most likely to be the culprits. You'll see a sign admonishing shoppers not to steal in English, Chinese, Portuguese, and/or Russian, but often not in Japanese. The Taiwanese sign doesn't seem to be an example of this, but here on the Internet no thought can go unexpressed, so here we are.

John Swindle said,

May 14, 2019 @ 3:46 am

A reader who understands this sign would presumably also understand it if written in standard Chinese, but the sign's author wants the reader to hear it in Hoklo. Nothing wrong with that.

Victor Mair said,

May 14, 2019 @ 5:38 am

There's a profound difference between reading the sign "written in standard Chinese" and "hear[ing] it in Hoklo".

Ivory Bill Woodpecker said,

May 14, 2019 @ 5:56 am

The Chinese civilization already achieved so much. One wonders how much farther it would have gone, had it NOT been handicapped by its bizarre writing system (Imagine trying to learn to read if the alphabet had 3,000 letters!).

John Swindle said,

May 14, 2019 @ 6:11 am

Nonetheless that may be the intent. To the native Mandarin speaker who knows enough Taiwanese to understand it (a large proportion of the sign's likely readership) it'll be noticeable and funny. To the native Taiwanese speaker who knows enough Mandarin to understand it (an even larger proportion of the likely readership) it'll be a noticeable reminder in the native language. 'S my guess, anyway.

Victor Mair said,

May 14, 2019 @ 6:22 am

@Ivory Bill Woodpecker:

You're on to something.

Antonio L. Banderas said,

May 14, 2019 @ 6:23 am

@John Swindle

What does " 'S " mean?

Victor Mair said,

May 14, 2019 @ 7:27 am

My guess is that "'S my guess" means "That's my guess".

Alex said,

May 14, 2019 @ 7:10 pm

@Ivory Bill Woodpecker

One of my first posts speculates that if China now wanted to immediately massively boost their GDP they could do it just by switching to pinyin or accepting pinyin as acceptable form like 2 scripts allowed or the mandatory use of both.

The benefits of acceptance by the non local users has been discussed and then it gives language a real chance of becoming international.

It would allow them to tap into their large population.

I don't know how many hundreds of millions of children who had potential in other areas other than memory / muscle memory were left behind.

Our best developer never finished HS and taught himself coding using English coding books because that's all there really was back then, He specifically said that it was the writing that limited him. He was the first in China to pass all the Amazon Web Services exams. Amazon China couldn't believe his scores.

Chris Button said,

May 14, 2019 @ 11:44 pm

Regarding "fumar", it might be worth noting that it is not part of the inherited lexicon in Spanish since /f/ would have shifted to /h/. Compare Spanish "hablar" with Portuguese "falar" for example.

John Swindle said,

May 15, 2019 @ 8:31 am

I saw the sign as mediating between speakers and readers of two languages, but I was mistaken. It's the local language written as it sounds to speakers of the prestige language, like eye dialect. That's why it's seen as humorous.

Katelyn said,

May 17, 2019 @ 9:58 am

No one speaks Standard Written Chinese. It is a written language that can be pronounced with a specific set of standardized phonemes. That set of standardized phonemes is known as 普通话.

Everyone speaks 普通话 with some kind of accent or variation. It may be an individual variation or a regional variation. But everyone speaks this spoken language with some kind of variation. In speaking 普通话, the national language, you may find regional variations, often influenced by the regiolects. Regional variations of 普通话 may change the tones, consonants and vowels; so as a result, foreigners may have a harder time understanding regionally accented 普通话 because the sounds are much closer to the regiolect's sounds.

The English language is not perfectly phonetic either. The vowels have many pronunciations, and a word's spelling is never consistent. For English speakers, they have standardized spelling. The Chinese equivalent to standardized spelling is the Chinese characters. At the very least, the Mandarin dialects are united by having Chinese characters instead of Hanyu Pinyin as the writing system. Though, I have encountered instances on the Yue, Hakka, and Min Wikipedias, in which they are indistinguishable from SWC. When the Min Wikipedias are written in Romanized form, a Mandarin speaker would understand 0%, and an actual native speaker of some kind of Min variant would probably also understand 0% because of unfamiliarity with the Romanized script.