Parsing of a fated kin tattoo

« previous post |

It's been a while since I've written about Chinese tattoos, although years ago they used to be a staple subcategory of our Chinglish-themed posts.

This intriguing one is too good to pass up:

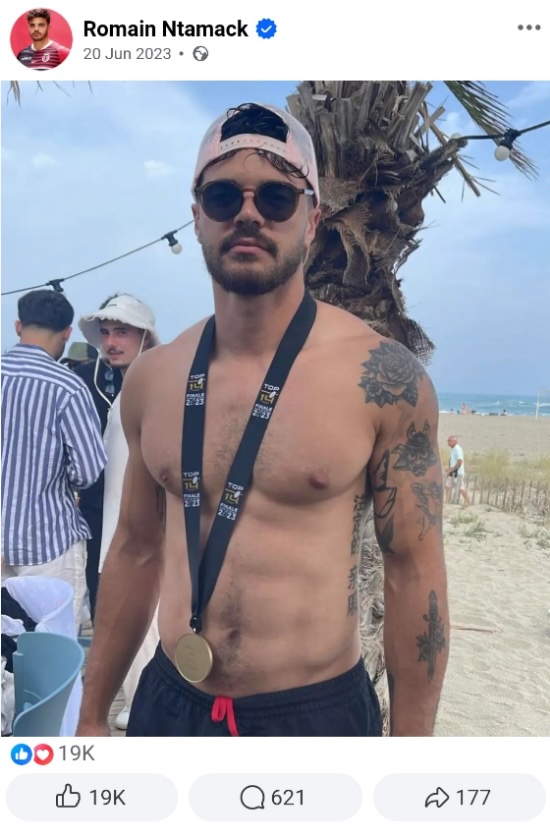

The bearer / wearer of this striking tattoo is the famous French (of partial Cameroonian extraction) professional rugby player Romain Ntamack (b. 1999). One photo is from his Facebook; the other one (the clearer one) is from the web.

The vertical sinographic tattoo on his left flank says:

zhùdìngde qīnqī 注定的 亲戚

("destined relatives; predestined family; fated kin")

I showed the tattoos to about half-a-dozen native speakers of Chinese, all of whom have graduate degrees in the Chinese humanities. None of them said outright that the phrase is grammatically incorrect, but they all said that it sounds unusual, that it doesn't seem like a natural Chinese expression.

None of them felt confident trying to come up with the correct interpretation of what Romain Ntamack wanted inscribed on his flank for the rest of his life. However, the majority said they think he meant something like "destiny is relative", and Chinese social media said the same thing.

Some of my informants said that foreigners usually know what they want their tattoo to say, and that they typically ask GT or other machine translator or the tattooist (if he knows Chinese) to turn the English into Chinese.

I interpreted the five characters as above as soon as I saw them: "destined relatives; predestined family; fated kin". Interestingly, all the machine translators I consulted interpreted the phrase exactly the way I did on first glance.

I cannot explain Romain's personal reason for sporting that particular tattoo, but I am deeply struck by one aspect of it. Namely, it displays an extraordinary command of Mandarin grammar. Notice the space between the modifier zhùdìngde 注定的 ("destined") and the noun qīnqī 亲戚 ("relative").

This is something I have long advocated for sinographic writing, because, without proper word parsing, there are many places in Chinese written texts that are ambiguous or confusing. Use of what is called fēncí liánxiě 分詞連寫 / 分词连写 ("word segmentation and linking") increases the amount of clarity in Chinese texts considerably. Often one may not know where one word ends and another begins. Correct parsing also helps with the understanding of the grammar and syntax of sentences.

Skeptics may say that I'm making a mountain out of a molehill, and that you don't need to know where words begin and end nor how to link syllables / morphemes correctly. Nevertheless, in half a century of correcting papers and reviewing translations, I can say with confidence that a goodly majority of errors in understanding Chinese passages is due to misdetermination of word boundaries and grammar attachment.

I have no idea who is responsible for that beautiful space between the adjective zhùdìngde 注定的 ("destined") and the noun qīnqī 亲戚 ("relative"), whether it be the tattooist, the tattooed, or a learned friend. Whoever it was, my hat's off to him / her.

Oh, additionally, the characters are elegantly executed, and they are neither upside down nor backward.

Selected readings

- "Hooked on pot" (7/9/13) — four large, exquisitely inscribed characters on the right flank of a person

- "Massachusetts is red(-faced)" (6/5/09)

- "Queen of the World" (3/10/12) — featuring one character that is upside down and backward

- "Tattoos as a means of communication" (9/1/12) — tattoos and the origin of writing

[Thanks to Kerts Deffle, Jing Hu, Xinyi Ye, Zhengyuan Zhang, Diana Shuheng Zhang, and Zhang He.]