"Focus" in Spanish?

« previous post | next post »

In a comment on "Reading Instruction in the mid 19th century", Rachel Churchill asked

Does contrastive emphasis (as in "George or his brother") exist in all languages? If not, which ones don't have it?

I've sometimes noticed non-native English speakers – even those whose pronunciation and accent are pretty good – failing to use it. For example, they might say "This one is fifty GRAMS, but the other one is twenty GRAMS", where a native speaker would emphasise the "fifty" and "twenty" rather than the "grams". I'm guessing it's because their native language doesn't use contrastive emphasis and maybe they've never been taught the concept, but I don't know this for sure.

I responded:

See Yong-cheol Lee, Bei Wang, Sisi Chen, Martine Adda-Decker, Angélique Amelot, Satoshi Nambu, and Mark Liberman, "A crosslinguistic study of prosodic focus", IEEE ICASSP, 2015. The abstract:

We examined the production and perception of (contrastive) prosodic focus, using a paradigm based on digit strings, in which the same material and discourse contexts can be used in different languages. We found a striking difference between languages like English and Mandarin Chinese, where prosodic focus is clearly marked in production and accurately recognized in perception, and languages like Korean, where prosodic focus is neither clearly marked in production nor accurately recognized in perception. We also present comparable production data for Suzhou Wu, Japanese, and French.

See also "Victor Hugo, hélas", 4/13/2024, "LÀ encore…", 4/14/2024, and "Intonational focus", 4/21/2011.

Roger C. continued the discussion:

In Spanish, focus contrast is generally achieved by changes in word order; syntax is more flexible than in English.

And I responded:

I'm guessing that (as in French) the word-order changes are combined with tonal and durational changes, and that in some cases (as in corrective focus on number or letter strings), the prosodic changes are the only cues.

In "Victor Hugo, hélas", I discussed the extreme ambiguity of the term "focus", the false prejudice that French doesn't allow prosodic focus, and a series of experiments that showing that "corrective focus" works in French essentially as it does in English, although there are languages (like Korean) where this is not true.

It would be easy enough for a native speaker of Spanish to perform a quick check of the same question: what happens when you correct someone's misunderstanding of a digit string, e.g.

No es "tres cinco seis", es "tres nueve seis".

(Sorry if that's not an idiomatic correction…)

Meanwhile, I thought I'd try looking for a different kind of focus in Spanish, as I did for French in "Victor Hugo, hélas":

[T]his encouraged me to finally look for "focus" in some samples of actual French talk. Or at least at one sample — I went to LibriVox, and randomly picked a reading of Victor Hugo's Le Dernier Jour d’un Condamné.

I noticed a relevant example in the second sentence of the preface — but a couple of paragraphs later, there's a sentence with a whole bunch of them:

Il le déclare donc, et il le répète, il occupe, au nom de tous les accusés possibles, innocents ou coupables, devant toutes les cours, tous les prétoires, tous les jurys, toutes les justices.

So for a comparison to Spanish, I randomly picked a Librivox reading of the first chapter of El 19 de marzo y el 2 de mayo by Benito Pérez Galdós.

And I was pleased to find a comparable passage early in the chapter, in a passage describing the narrator's reactions to work as a typesetter (starting at 3:32.844 of the recording, emphasis added):

Poníalos yo en movimiento, y de aquellos pedazos de plomo surgían sílabas, voces, ideas, juicios, frases, oraciones, períodos, párrafos, capítulos, discursos, la palabra humana en toda su majestad; y después, cuando el molde había hecho su papel mecánico, mis dedos lo descomponían, distribuyendo las letras: cada cual se iba a su casilla, como los simples que el químico guarda después de separados; los caracteres perdían su sentido, es decir, su alma, y tornando a ser plomo puro, caían mudos e insignificantes en la caja.

¡Aquellos pensamientos y este mecanismo todas las horas, todos los días, semana tras semana, mes tras mes! Verdad es que las alegrías, el inefable gozo de los domingos compensaban todas las tristezas y angustiosas cavilaciones de los demás días. ¡Ah!, permitid a mi ancianidad que se extasíe con tales recuerdos; permitid a esta negra nube que se alboroce y se ilumine traspasada por un rayo de sol.

I set them in motion, and from those pieces of lead emerged syllables, voices, ideas, judgments, phrases, sentences, periods, paragraphs, chapters, speeches, the human word in all its majesty; and then, when the mold had played its mechanical role, my fingers decomposed it, distributing the letters: each one went to its place, like the simples that the chemist keeps after they have been separated; the characters lost their meaning, that is, their soul, and, returning to pure lead, fell mute and insignificant into the box.

Those thoughts and this mechanism every hour, every day, week after week, month after month! It is true that the joys, the ineffable joy of Sundays compensated for all the sadness and anguished musings of the other days. Ah! Allow my old age to be enraptured by such memories; allow this black cloud to rejoice and be illuminated, pierced by a ray of sunlight.

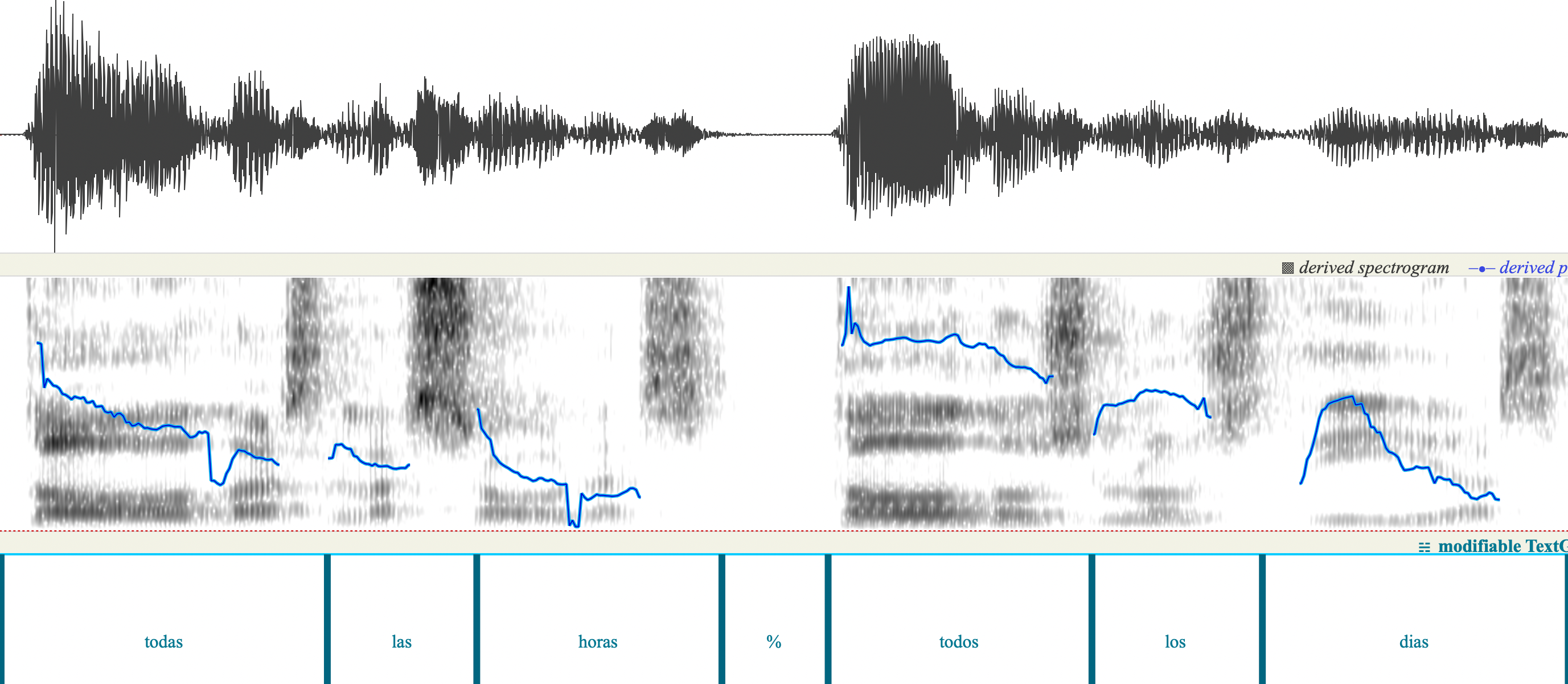

Here's the sentence where todas/todos are "focused", ithe speaker referencing all rather than some of the hours and days:

¡Aquellos pensamientos y este mecanismo todas las horas, todos los días, semana tras semana, mes tras mes!

And zeroing in:

In addition to higher pitch and greater vocal effort, the stressed syllables of "todas" and "todos" are lengthened — see below for a comparison with an unfocused version.

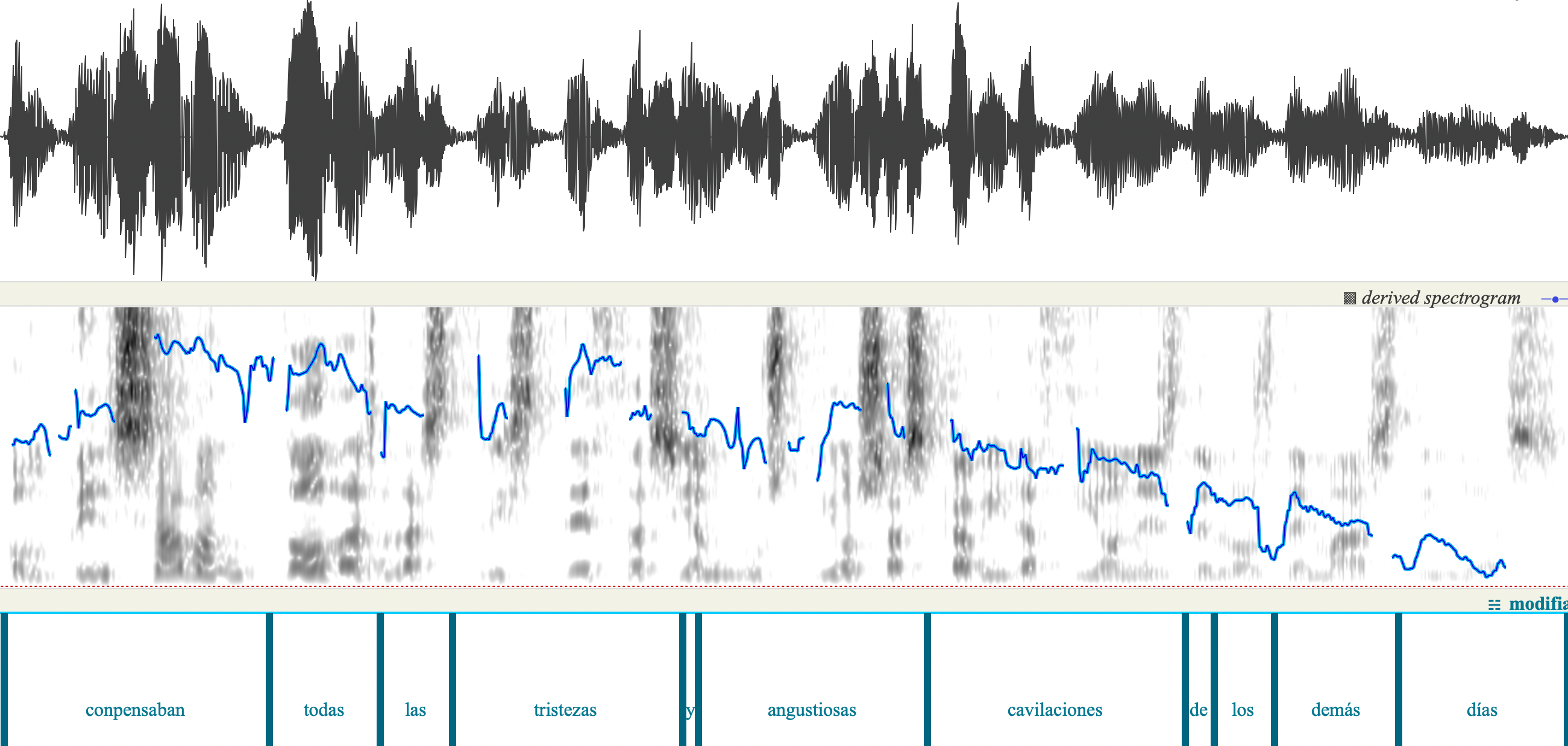

The very next sentence has another use of todas, this one naming all the sadnesses and anguished musings, without (much of?) an implied contrast to some of them:

Verdad es que las alegrías, el inefable gozo de los domingos compensaban todas las tristezas y angustiosas cavilaciones de los demás días.

Zeroing in a bit:

compensaban todas las tristezas y angustiosas cavilaciones de los demás días

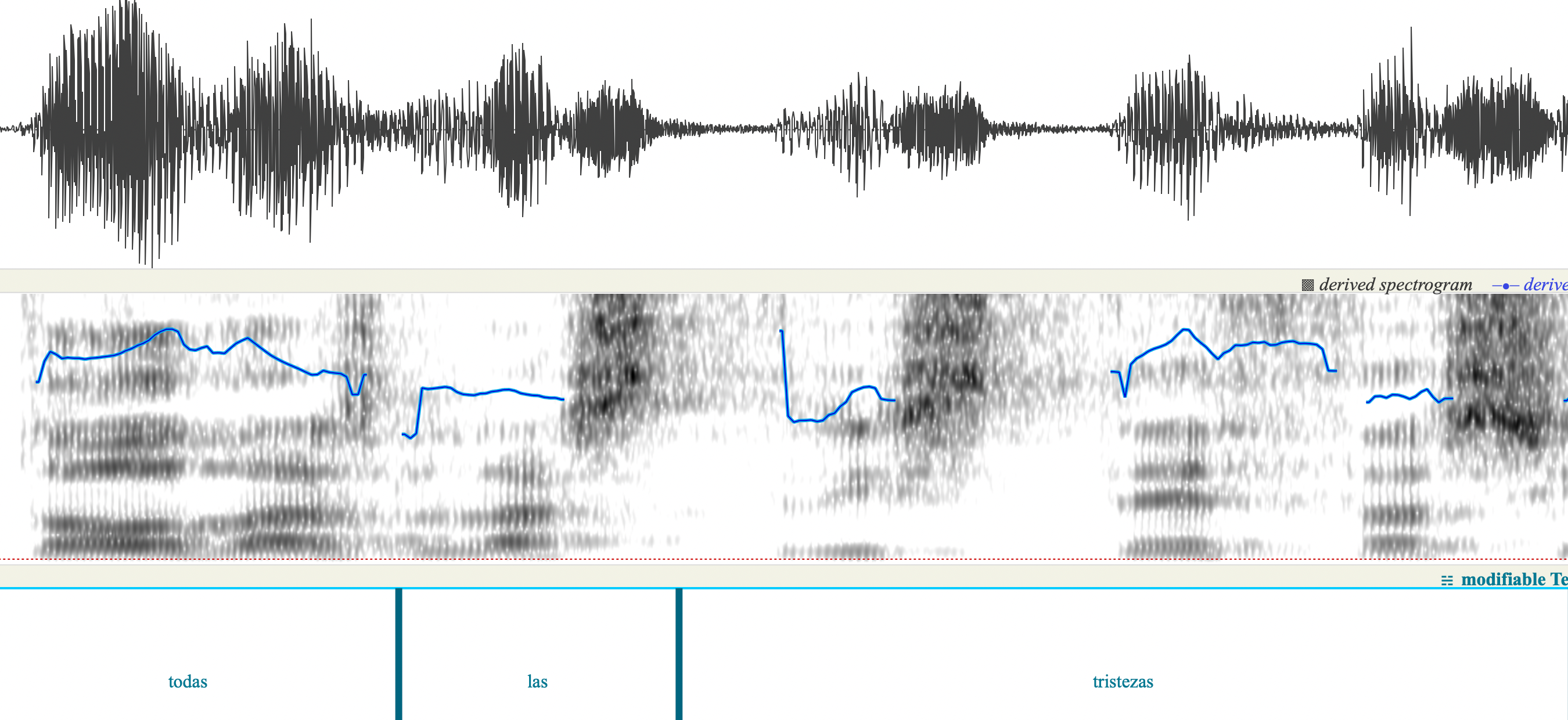

…And a bit further:

todas las tristezas

In this case, the pitch of "tristezas" is essentially the same as that of "todas".

And a comparison of syllable and word durations underlines the difference:

| Phrase | First Syllable | Whole Word |

| todas (las horas) | 280 ms | 503 ms |

| todos (los días) | 242 ms | 438 ms |

| todas las tristezas | 144 ms | 329 ms |

Chris Button said,

August 18, 2025 @ 8:50 pm

The pioneer in comparing English with Spanish intonation was surely Roger Kingdon (1891 – 1984). I recall the handful of pages at the back of his 1958 "The Groundwork of English Intonation" as being amazingly insightful and informed for the time.

[myl: FWIW, the cited pages are here.]

Bob Ladd said,

August 19, 2025 @ 12:58 am

This gets complicated fast. As someone who spoke French near-natively in my teens and twenties, and as someone who has spent more of his life thinking about deaccenting and focus than anyone should have to, I don't hear the examples in the Victor Hugo audio clip as anything like the English examples with BLUE triangle or FIFTY grams that this discussion started out with a few days ago. The pitch peaks on all the occurrences of tout (tous, toutes, etc.) in the long rhetorical sequence do not create "focus" in the same way the same way as the pitch peaks in those English examples; rather, because the nouns in each phrase (judges, courts, juries….) are different, the speaker's rendition of the phrases somehow emphasizes the rhetorical repetition.

If you translate the occurrences of tout into English with "every", you can get a similar effect, and the phonetic difference in English is clear. The version with "focus" on "every" – i.e. EVERY judge, not just some judges – drops down rapidly toward the bottom of the speaker's range on "every" and stays there for the noun, whereas the rhetorical repetition version stays high on "every" and falls rapidly on the noun.

I will try to provide audio examples that MYL can post. And it would be great if a native French speaker could confirm or challenge my interpretation of the intonation in the passage from Victor Hugo.

Jarek Weckwerth said,

August 19, 2025 @ 5:04 am

I will rephrase my comment on that original Hugo post from yesteryear: To me, the choice to stress todas in these examples feels mostly actorly/interpretative, and is completely optional. It would be just as reasonable (or maybe even better because that's where the contrast really is) to put the focus on the nouns. The two options are both legitimate, as opposed to the real (and non-negotiable) contrastive focussing when correcting the numbers.

Is this completely misguided because I'm cr*p at Romance?

Mark Liberman said,

August 19, 2025 @ 5:32 am

@Jarek Wekwerth: "To me, the choice to stress todas in these examples feels mostly actorly/interpretative, and is completely optional. "

This is certainly true. But I think the choice does convey the speaker's intent to emphasize "todos/todas" as opposed to (and thus in contrast with) "algunos/algunas".

Mark Liberman said,

August 19, 2025 @ 5:46 am

@Bob Ladd: "This gets complicated fast."

Agreed. In the French and Spanish examples under discussion, the emphasized words are higher in pitch, and the following words are lower, but not as low and flat as they might be.

A plausible hypothesis is that this lowering, like other forms of phonetic lenition, is a gradient phenomenon, with complete deletion (in this case of the word-associated pitch movement) as one end of a phonetic process rather than (in all cases?) a qualitative phonological substitution (of nothing for something). And in fact that's what we see in English "focus" cases, where post-focus pitch movements may remain statistically distinguishable even when they're not perceptually salient.

Along with many other studies, our paper on contrastive focus in number strings showed that both French and Mandarin Chinese marked contrast prosodically as effectively as English did. But in Mandarin, the post-contrast tonal features are lenited, not deleted. French and Spanish seem similar to me — and English can be too.

English is freer with extreme lenition (→ deletion) of unstressed vowels than French or Mandarin or Spanish are — and maybe what's happening here is similar?

Peter Cyrus said,

August 19, 2025 @ 5:46 am

I'm not a native speaker of either French or Castilian Spanish, but I've lived more than a decade in each country. My first thought on reading this post was that every language probably has a way to mark contrastive focus, but not necessarity (only) with phonetic stress. In both French and Spanish, I think unexpected focus is marked with different phrasing more than is the case in English.

For example, in Spanish, when I have to repeat my phone number because I said it faster than the cashier's fingers could type, I don't stress the (first) wrong digit; I just repeat the number with the usual intonation pattern. It's easier for them to hear the entire number again: repetition is easier than correction.

Mark Liberman said,

August 19, 2025 @ 5:54 am

@Peter Cyrus: "in Spanish, when I have to repeat my phone number because I said it faster than the cashier's fingers could type, I don't stress the (first) wrong digit; I just repeat the number with the usual intonation pattern."

Take a look at our paper on contrastive focus in number strings, where the speakers of French and Mandarin corrected a mistaken number string by repeating the whole string, but with clear prosodic marking of the (single-digit) correction. They were not told to do this — it's just how they performed the task.

As the paper notes,

[T]here was a clear and consistent effect of focus in all the parameters for English and in Mandarin Chinese. Focused digits were clearly indicated by greater duration, f0, and intensity. These languages also showed clear post-focus compression [15, 21, 23], with reduced duration, f0, and intensity on the post-focus digits.

Were the studied languages all the same? No,

We have gathered production data for three additional languages/varieties: Suzhou Wu, Tokyo Japanese, and Standard French.

Suzhou Wu and Tokyo Japanese are quite similar to Korean, in that measures such a duration, f0, and intensity do not show patterns clearly identifying the corrected digit. Suzhou Wu also shows F0 rising in the positions adjacent to the focused digit, especially when the focus is in the middle of a prosodic phrase. French, on the other hand, shows the focused digit well marked by increases in intensity, duration, and (to a lesser extent) F0.

My guess is that Spanish speakers would be similar to French speakers in these measures.

(I believe that French also showed somewhat less "post-focus compression" than English and Mandarin, though the paper doesn't provide evidence and I could be wrong.)

han said,

August 19, 2025 @ 10:25 am

Speaking about morphological focus marking, there're affixes in Santali such as -ge/gw ito mark focusness, -do to topicalize, etc.

Ari said,

August 19, 2025 @ 12:17 pm

I recommend this video by Geoff Lindsey describing how accenting & deaccenting syllables works differently in English than some other languages (with examples) and how (de)accenting relates to contrast, "given information", and repetition.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y5jD5SyH3EM

Peter Taylor said,

August 21, 2025 @ 4:33 am

@Peter Cyrus, repeating the whole number rather than trying to explain the context for a partial repetition may be easier, but to mark the difference between sesenta and setenta I do find anecdotally that emphasising the critical syllable improves recognition accuracy.

jih said,

August 21, 2025 @ 9:36 pm

Going back to the original observation, what is very difficult for (us) Spanish speakers to acquire is the English accent retraction rule. The most difficult thing is arbritrary lexical contrasts like "GREEN street" vs "Green AVEnue", "apple pie" vs "apple cake" (I forgot which one has nonfinal accent in US English), followed by indefinites, like in "I SAW someone". (I know it is wrong, because I have learned it explicitly, but "I saw someONE" sounds perfectly fine to me) Compounds of the type "GREENhouse" (vs the phrase "green house") are much easier. Contrastive focus, as in "not twenty grams, but FIFTY grams", is even easier, but performance would not be error-free, because Spanish does not have obligatory deaccentuation here either; which does not mean that one cannot focalize the numbers in this example; only that it is also ok to say things like "no veinte gramos sino cinCUENta GRAmos".

Bob Ladd said,

August 22, 2025 @ 5:04 am

@jih – Thanks for adding this – you express an important part of the problem by referring to what's going on in English as "accent retraction". I think that is precisely what's going on, and precisely what speakers of Romance languages find so difficult. Given a phrase with two content words (like Green Street, fifty grams, etc. etc.), the normal stress pattern in most contexts in the Romance languages is weak-strong, whereas in English both weak-strong and strong-weak are found, with the difference expressing a variety of lexical, grammatical, and pragmatic differences (as in your examples).

Talking about this gets confusing because English speakers tend to think about where the main accent IS, not where it ISN'T (i.e. they concentrate on where "emphasis" or "prominence" occurs in the phrase). But the Romance point of view – that English is moving the main accent OFF the second word – is a lot closer to capturing what's going on in many cases (hence "deaccenting", "retraction", etc.

Jarek Weckwerth said,

August 24, 2025 @ 4:20 am

@jih: "no veinte gramos sino cinCUENta GRAmos" — Is it OK to skip the repeated noun? I.e. say no veinte gramos sino cincuenta?