LÀ encore…

« previous post | next post »

Continuing my anecdotal exploration of "focus"-like phenomena in French, I dove into a random point in the middle of a random Radio France podcast ("Libre Pensée – L’Europe, l’Union européenne et les élections européennes", 4/14/2024). And within a few seconds, I heard this, where the apparent "focus" on là caught my attention:

Euh mais pour bien comprendre il faut là encore revenir à l'histoire —

décidément nous faisons un peu un cours d'histoire aujourd'hui

(Google translation for those who need it…)

Zeroing in a bit:

The performance of "LÀ encore" (= "THERE again") in that phrase contributed the title of this post, for an obvious reason. Note that in addition to the higher pitch and louder amplitude, là also has about 100 msec of glottalized onset.

The following phrase lacks any obvious "focus"-like elements, but does illustrate some extreme lenition phenomena — more on French lenition in the future…

A little bit later in the same podcast, we get

Certains peuvent le penser.

Mais là encore, je pense que le mieux c'est euh de se rapporter

à la fois à l'histoire et à des faits précis.

L'histoire d'abord.

(The Google Translate version)

Phrase by phrase, again:

Interestingly, here "là encore" is mostly backgrounded, with "là" short, soft, and low in pitch, while "encore" just has the more-or-less obligatory medial-phrase-final rise.

In the next phrase, à la fois and et have the kind of parallel-marking "focus" we saw before with toutes/tous…

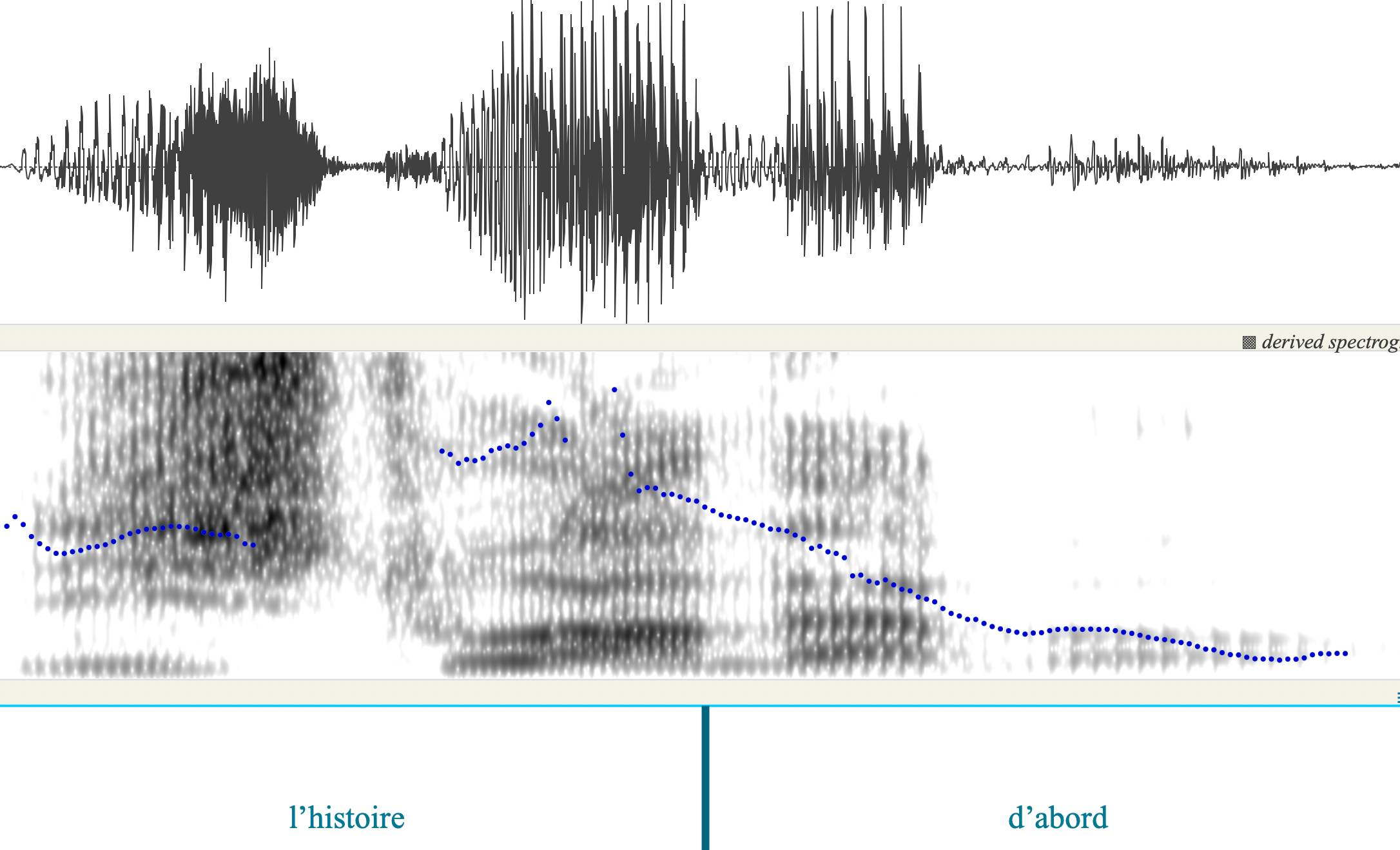

And in the last phrase, histoire seems to get a strong prosodic "focus":

Random anecdotes like these are easy to find, and confirm my impression that French speakers make frequent communicative use of the prosodic features — duration, pitch, amplitude — that are associated with (the many meanings of) the term "focus" in languages like English.

That's not to say that French prosodic "focus" is the same as English prosodic "focus". But we'll never learn what's going on if we continue to maintain the fiction that prosodic "focus" doesn't exist in French.

One final note on possible universality. On one hand, these prosodic features are iconic — we are not going to find a language where emphasis, contrast, novelty, etc., are signaled by shorter duration, lower pitch and amplitude, more co-articulation, etc. However, these features are modulations of the basic prosodic systems of the language in question, as we can see clearly in a tone language like Mandarin Chinese, where we have a good idea of what patterns are being modulated. And there do seem to be languages (or varieties) where the uses of such modulations are much more restricted. The dimensions of the relevant typology are mostly unknown — or rather, have been presented in various radically over-simplified and empirically empty ways.

AntC said,

April 14, 2024 @ 6:31 pm

that are associated with (the many meanings of) the term "focus" in languages like English.

Thank you Mark. English is a stress-time language, which means amot that each content word marks a stressed syllable, and if you want to put focus on that word, you extra-stress that syllable. (And word stress is phonemic to an extent.)

French is a syllable-time language. What I get told is polysyllabic words should be pronounced with equal stress on each syllable. (Being a native Brit, I find it very hard to keep to that.)

For a given French polysyllabic word, is there a preferred syllable that will get the focus? Is it consistent?

There is also a phenomenon (to my ear more noticeable in the rural South/away from Paris) of prosody giving a falling tone at the end of a phrase. This isn't just 'tailing off' into nothing, but (I'd say) a focus-like phenomena: I've completed that thought. Traditionally/the caricature (and to my ear, actually) speakers might 'invent' [**] a vowel at the end of a word to carry that falling tone. I've heard 'ving-te'.

[**] That is, famously French orthography has all sorts of vowels/historical remnants at the end of words, that don't usually get pronounced — except in this phenomena. But even words that have always ended in a consonant get a schwa tacked on.

Caricature: a Sacha Distel comic song of Parisians en vacances in the South. Note in the refrain 'place' with two syllables. (Contrast 'd'placé' with two syllables, as expected.)

AntC said,

April 14, 2024 @ 6:44 pm

@Chris B I personally think the word "stress" is more abused than "focus".

Errk apologies to Chris, then. In my above comment, I mostly avoided 'focus' given Mark's "perniciously"; and preferred 'stress'. Help! more technical terms needed.

Mark Liberman said,

April 15, 2024 @ 6:15 am

@ Ant C: "English is a stress-time language […] French is a syllable-time language"

The rest of your comment suggests that you mean only that English has (dynamic) word stress, while French doesn't. Which is true, though the implication that there's a binary typology here is a radical (though common) over-simplification.

But the terminological choice — usually "stress timed" vs. "syllable timed" — implies isochronism of stress feet in English and syllables in French. And this is totally untrue, though widely believed. See " Stress timing? Not so much", 5/8/2008.

Some true believers have proposed the back-off position that inter-stress intervals (or inter-syllable intervals) are somewhat more isochronous than they would be without a tendency towards stress-timing or syllable-timing. This is also false.

So where does the X-timing intuition come from? In my opinion, it does reflect something about the psycho-motor organization of speech — though the typology is multi-dimensional, and even in that space, the idea of a binary choice between "stress-timed" and "syllable-timed" is at best a radical over-simplification. For more background, see "Slicing the syllabic bologna", 5/5/2008, "Another slice of prosodic sausage", 5/6/2008, and "Syllable rhythm in English and Mandarin", 2/28/2023.

Mark Liberman said,

April 15, 2024 @ 6:57 am

@Ant C: "English is a stress-time language, which means amot that each content word marks a stressed syllable, and if you want to put focus on that word, you extra-stress that syllable."

One more factual correction: As Beth Ann Hockey showed in her 1998 dissertation ("The interpretation and realization of focus: an experimental investigation of focus in English and Hungarian"), the duration and amplitude effects of (English) focus apply to the whole focused word or constituent, not just its most stressed syllable.

The effects on pitch are mediated by the nature and association of (typically stress-linked) pitch accents and (boundary-linked) junctural tones, but again, it's not necessarily just one syllable.

AntC said,

April 16, 2024 @ 5:29 am

Thank you Mark for those links. I see the English-Mandarin comparison generated quite a bit of commentary, including from me.

I'm happy to concede "radical over-simplification". OTOH my take from those comments is that there is a phenomenon people can sense — and apparently your "fancy devices" can't. Also just listening to Mandarin as spoken in Taiwan (and I'm listening to the music of it, I don't claim to understand — which is probably a _better_ measure), it is not a good exemplar of the phenomena that's over-simplifyingly called 'syllable-timed', and of which French is a much better exemplar. So would it be possible to re-run that breakfast experiment with two languages considered to be at the extreme ends of this (alleged) phenomena?

My doubts aren't negating your key thesis here

… [don't] continue to maintain the fiction that prosodic "focus" doesn't exist in French.