Victor Hugo, hélas

« previous post | next post »

Focus is perhaps the single most perniciously ambiguous word in the field of linguistics. In Beth Ann Hockey's 1998 dissertation, "The interpretation and realization of focus: an experimental investigation of focus in English and Hungarian", she wrote:

Linguists have associated the word “focus” with a wide variety of phenomena. In addition a wealth of other terms including “new,” “emphasis,” “stress,” “rheme,” “comment,” “accented,” “prominent,” “informative” and “contrast” have been attached singly or in combination to phenomena that seem to be the same as, similar to or overlapping with those that have been called focus.

Beth Ann quotes a few relevant passages from Lewis Carroll, including

‘That's a great deal to make one word mean,’ Alice said in a thoughtful tone.

‘When I make a word do a lot of work like that,’ said Humpty Dumpty, ‘I always pay it extra.’

The other day, a talk about perception of prosodic "focus" by French and English adults and children reminded me of this ambiguity. It also brought up an issue that I've been wondering about for more than 50 years, since Jacqueline Vaissière half-persuaded me that French lacks any prosodic signaling of "focus". I expressed this half-persuasion in "Intonational focus", 4/29/2011, where I wrote

There are some languages (e.g. French) where intonational focus apparently doesn't exist, at least not in the same way as in English. Instead, I'm told, speakers must use cleft constructions ("C'est X qui Y") or other re-phrasing in order to do the things that English speakers can do with intonation alone, such as to adapt a proposition in response to different possible questions, or to underline a parallel contrast.

Because I sometimes hear native speakers of French using what seems to me like intonational focus — sometimes combined with syntactic methods for signaling information structure, and sometimes not — I've wondered whether intonational focus might be stigmatized in standard spoken French, rather than completely absent. But I accept that some things that English speakers are happy to do with intonation are really impossible in French, for example focusing or contrasting prepositions or verbal auxiliaries: "It's *under* the box (not *top* of it)"; "It *was* there (but now it's gone)".

And a few years later, a few of us proved that French speakers encode corrective focus in number strings prosodically, just like speakers of English and Mandarin Chinese do, but unlike speakers of Korean and Japanese (Yong-cheol Lee, Bei Wang, Sisi Chen, Martine Adda-Decker, Angélique Amelot, Satoshi Nambu, and Mark Liberman, "A crosslinguistic study of prosodic focus", IEEE-ICASSP 2015).

Corrective substitution (e.g. "3 1 5 6" in place of mis-heard or mis-remembered "3 1 9 6" is only one of the many things that the word "focus" is used for; and "focus" on one number in a string is a case where there are no easy syntactic solutions. So this is just one small skirmish in the larger "prosodic focus in French?" battle, which in turn is just part of the "prosodic theory" campaign in the "communicative intention" wars.

But anyhow, this encouraged me to finally look for "focus" in some samples of actual French talk. Or at least at one sample — I went to LibriVox, and randomly picked a reading of Victor Hugo's Le Dernier Jour d’un Condamné.

I noticed a relevant example in the second sentence of the preface — but a couple of paragraphs later, there's a sentence with a whole bunch of them:

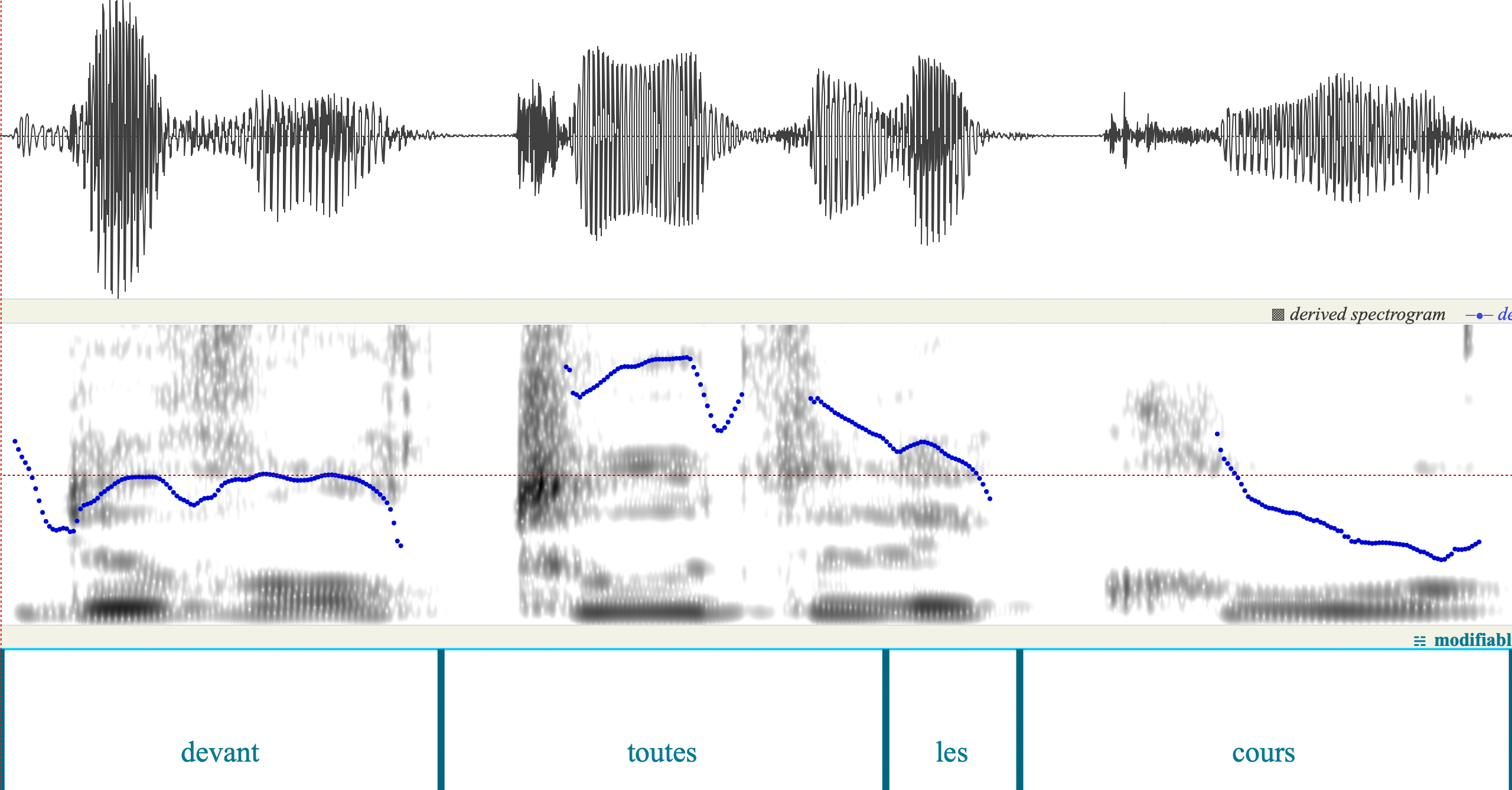

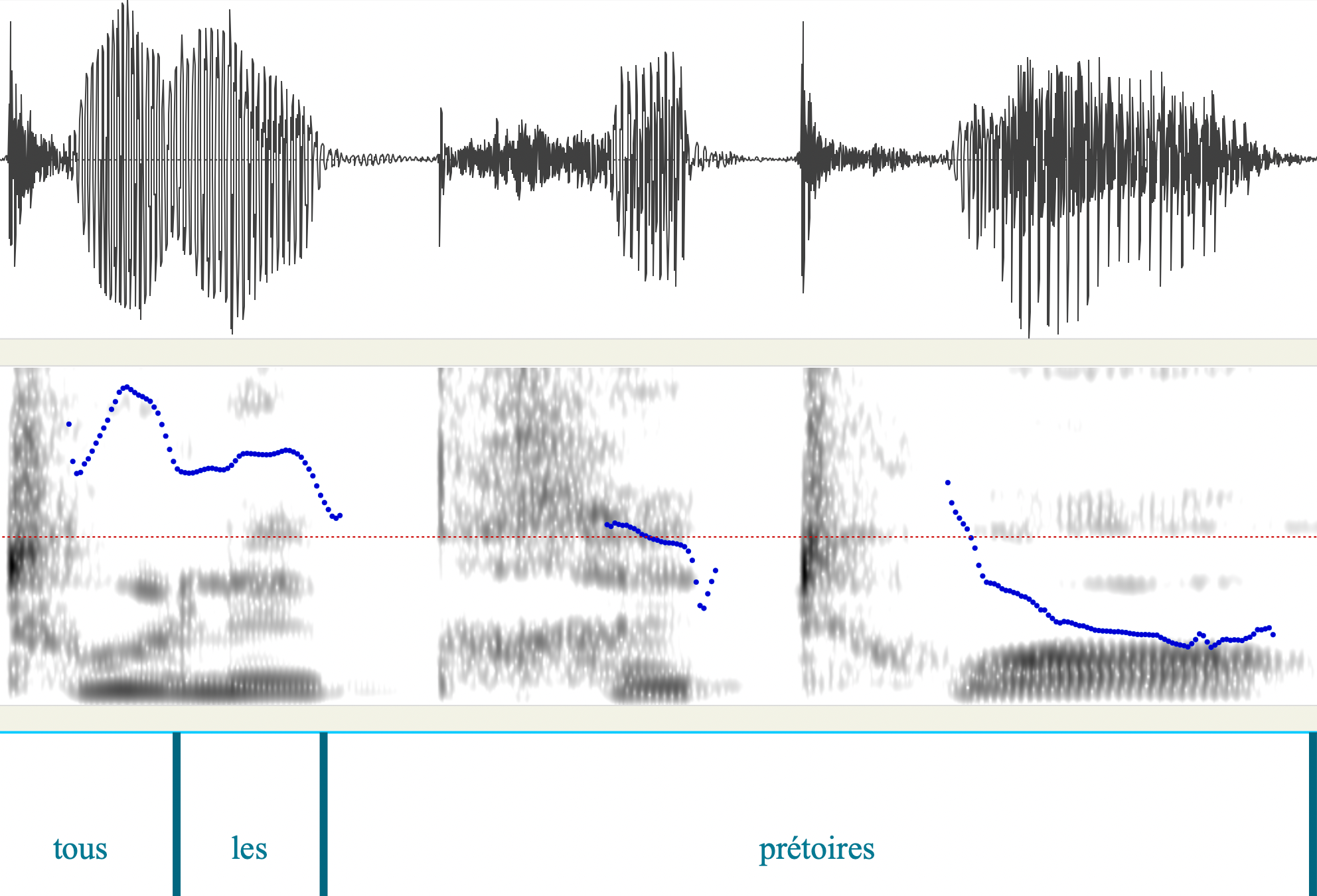

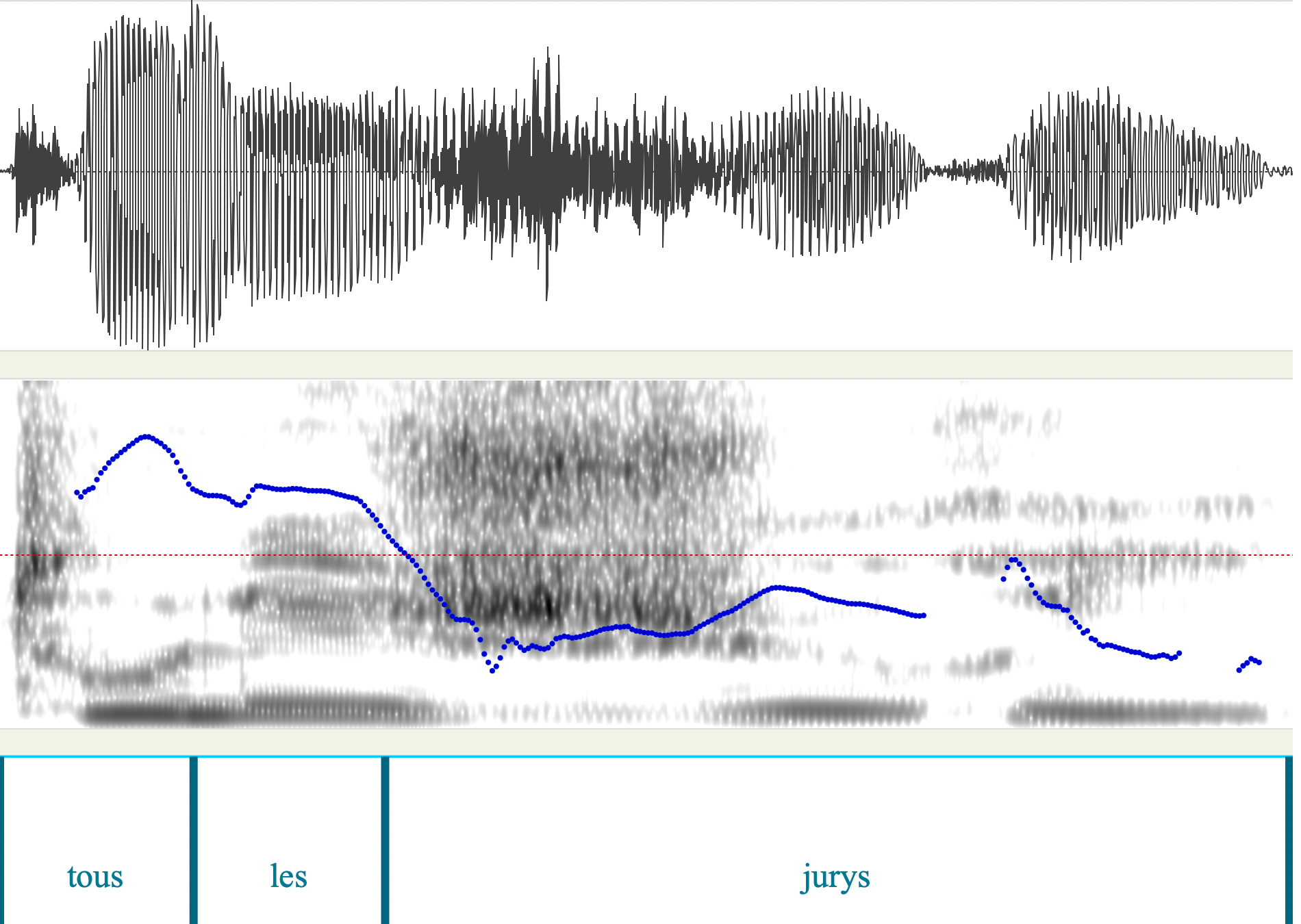

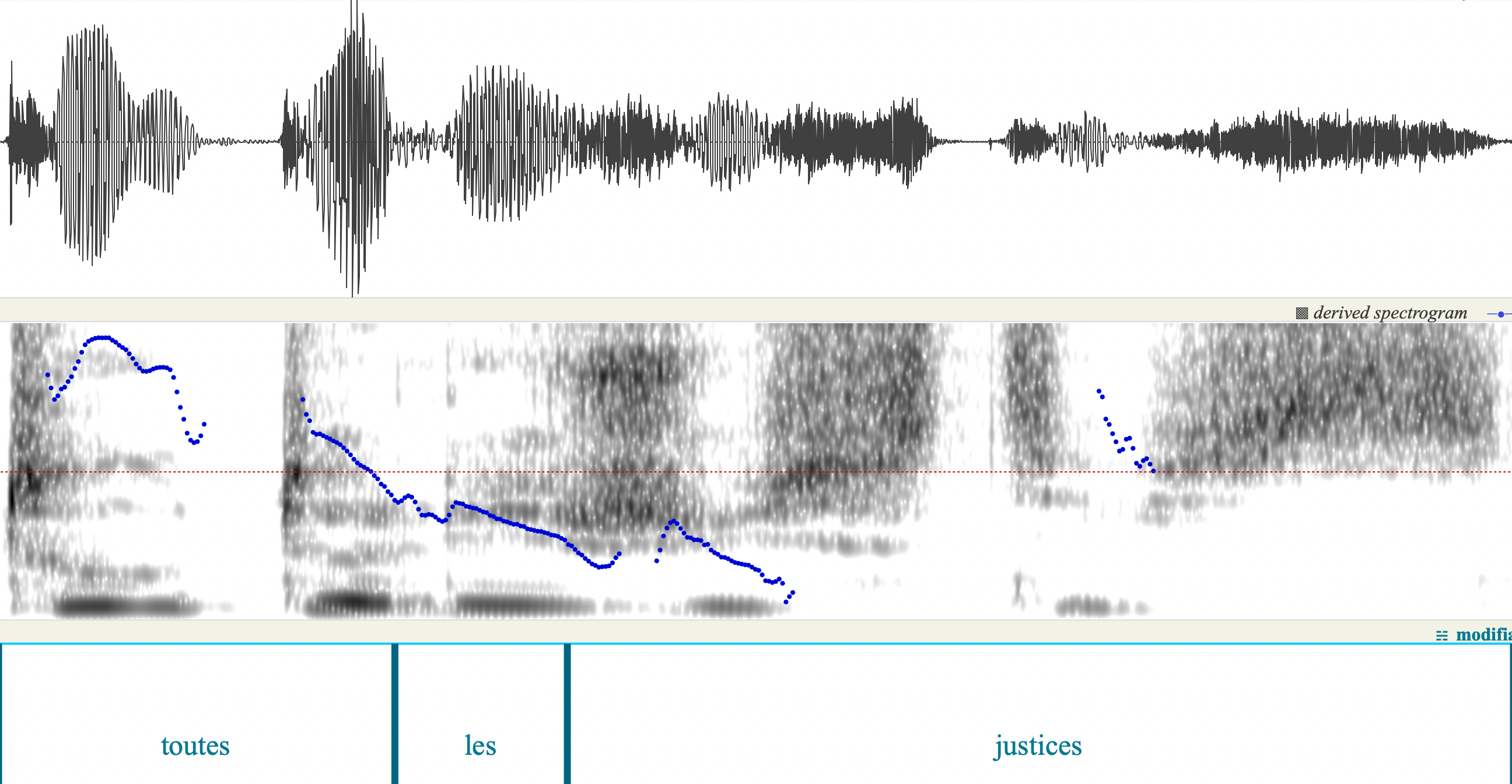

Il le déclare donc, et il le répète, il occupe, au nom de tous les accusés possibles, innocents ou coupables, devant toutes les cours, tous les prétoires, tous les jurys, toutes les justices.

(If your French is not up to the job, I'll turn you over to Google Translate, which is close enough…)

Let's skip the de-accentuation (or whatever it is) of donc in the first phrase, and focus on the adjectives tous or toutes in the final four phrases. Aligned pitch tracks are given below, and you can hear and see that in each case, the word tous or toutes is "focused", in some sense of that term:

Is this just "emphasis"? Or is it indicating the choice of all rather than some or most?

Could the reader have placed the "focus" in those phrases on cours, prétoires, jurys, justices? If she had done so, how would it change the meaning?

I'm not confident enough in my knowledge of French to be sure — but I believe that in an English translation with a similar sequence of phrases, my choice would matter:

… all the courts, all the tribunals, all the juries, all the justice systems

… all the courts, all the tribunals, all the juries, all the justice systems

And I imagine that the French situation is similar.

[Note: this post's title is the common version of what André Gide is said to have said when asked to name the greatest French poet — for more on the folklore and the facts, see Justin O'Brien, "Hugo,-hélas!", French Review 1964.]

[Also, Beth Ann's Lewis Carroll quotes — and a lot of other good stuff — can be found in Chapter VI of Through the Looking Glass.]

See also "LÀ encore…"

JPL said,

April 13, 2024 @ 8:43 pm

My candidate for "perhaps the single most perniciously ambiguous word in the field of linguistics" would be "form".

I'll have to look at the indication of contrastiveness in West African tone languages, which is primarily done by syntactic mechanisms, but it seems loudness and width of gap between high and low tone may enter in as well. Words like "focus", "stress", "emphasis" often refer to a relation of contrastiveness, but specifying what it is that is "focused", etc. is always the problem. "Foreground vs. background" (like asserted vs. presupposed) is a related distinction, taken maybe from visual perception, that is described using the term "focus".

Chris Button said,

April 13, 2024 @ 8:51 pm

I'm not sure if stigmatized is the right term, but i think this is indeed the gist of it. It happens in other languages too, where changing the phrasing is preferable to using intonational focus. But that should by no means imply that people don't use the intonational focus when the situation warrants it.

So here, using intonational focus is clearly preferable for narrative effect (and also presumably because changing the phrasing would be very awkward).

I personally think the word "stress" is more abused than "focus".

JPL said,

April 14, 2024 @ 1:46 am

The sentence "Is this just "emphasis?" in the OP is a rhetorical question. (See "I imagine the French case is similar.") The point is that it can't just be "emphasis" or "focus" tout court; there has to be some semantic or pragmatic element of what is expressed that is meant to be noticed. In these cases it's a point of relevant difference (e.g., totality vs. less than totality). The element shifted from may be present (assumed or expressed) in the previous text. This point of difference is indicated and made perceptually salient here by higher pitch and increased loudness. In tone languages the point of difference typically can be indicated by putting the element that expresses it somewhere that it normally isn't, like at the beginning of the sentence, perhaps with a segmental morph indicating assertion. The ambiguity of the term results from failing to make the necessary distinctions.

Jarek Weckwerth said,

April 14, 2024 @ 3:41 am

I think that the French example here demonstrates the prosodic realization of that specific rhetoric device, i.e. repetition. Which of the choices you go for after that (all or the nouns) is sort-of secondary.

But in general I wanted to say that my L1 (Polish) is like that. I haven't done any research as such, but I've taught English intonation to Polish learners as part of an advanced pronunciation course. It needs to be taught expressly since it's very foreign to Polish. One particular offender is the fall-rise for given/definite (vs. new/indefinite) information, as per David Brazil's communicative approach.

Polish does that job using word order (much freer in general), and there is a strong preference for new/indefinite material to be "foregrounded" by placing it at the end of the clause with the default intonation (rather than modifying the intonation, which, all the same, is an option).

This gets reflected in translated>dubbed material in interesting ways: (1) Cheap translator isn't aware of how this works. (2) They preserve the English word order (i.e. do what a cheap translator does = simply substitute the lexical items). (3) Cheap voice talent needs to read quickly, on the spot, without an initial analysis. (4) They apply the default intonation (tonic stress on last content word). (5) Weirdness ensues, sometimes to the point of incomprehensibility. (Phonetician hat off > Great annoyance ensues.)

(1) A new kid has joined the playgroup. > Nowe dziecko doszło do grupy w przedszkolu. (Should preferably be Do grupy doszło nowe dziecko.) (2) Unprepared voice talent puts tonic stress by default on playgroup. (3) This can only really be interpreted as The new kid… which is wrong in the context of the narrative.

Sorry for the length of this.

Jarek Weckwerth said,

April 14, 2024 @ 3:43 am

My goodness I wrote that long thing and forgot to mention the crucial bit: It is in fact possible to put the tonic stress on nowe dziecko and save the meaninig-in-context. But that I think that is much more of an option in spoken language, and in writing there is a very strong preference for the movement-for-focus solution.

Chris Button said,

April 14, 2024 @ 3:57 am

Yes, although it might be worth noting that "tone" languages do still use intonational tone, but they combine it with lexical tone. A "non-tone" language only uses intonational tone. So in that sense, all languages are tone languages.

Timothy Rowe said,

April 14, 2024 @ 5:17 am

Whoever Beth Ann is quoting, I don't think it's Lewis Carrol, because that dialogue isn't in Through the Looking Glass, the only place Humpty Dumpty and Alice meet. I suspect it's a line from one of the screen adaptations, wrongly ascribed to Carroll.

[(myl) As others point out below, you're wrong. Here's an image of the quotation in context from the 1872 edition of Through the Looking Glass.]

Mark Liberman said,

April 14, 2024 @ 5:20 am

@Jarek Weckwerth: "that is much more of an option in spoken language, and in writing there is a very strong preference for the movement-for-focus solution."

See "'On the difference between writing and speaking'" (12/23/2016) and "The narrow end of the funnel" (8/18/2016).

Doug said,

April 14, 2024 @ 6:48 am

@Timothy Rowe

If that's a misquote, it's a widespread one. It shows up in what purports to be the text of Through the Looking-Glass in various places, like here:

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Through_the_Looking-Glass,_and_What_Alice_Found_There/Chapter_VI

Now you have me wondering but I can't find a physical copy to check that.

Stephen Goranson said,

April 14, 2024 @ 7:36 am

The quote from "That's a great deal" to "pay it extra." is accurate, according to The Complete Works of Lewis Carroll, Modern Library edition page 214.

Coby said,

April 14, 2024 @ 8:28 am

In French, the kind of emphasis implied by intonational focus in English is usually achieved by adding bien.

This habit may carry over into writing (replacing, say, underlining). I have an example of it in an old passport.

When, in 1986, France required (for some retaliatory reason or other) visas for American tourists, the one I got at the French consulate in Barcelona has the validity date (06/01/87) written over correcting fluid, with an added "JE DIS BIEN VALABLE JUSQU'AU 06/01/87" handwritten by the vice-consul.

Kate Bunting said,

April 14, 2024 @ 9:06 am

Yes, the quote is in my 1908 edition of 'Through the Looking-Glass', to which I was introduced at my father's knee in the 1950s.

Jonathan Smith said,

April 14, 2024 @ 9:59 am

A tone language wrinkle are systems with "citation" (or "phrase final"/"emphatic") vs. "sandhi" (or "light") allophonic variants where a single tone contour can characterize some citation value AND a (different) sandhi value. So in Taiwanese, "emphatic" Tone 2 and "light" Tone 3 are both "high falling," written identically when one wishes to indicate phonetic (not phonemic) values. But such pairs must actually be different in terms of length, loudness, or something… Mandarin influence (and indeed borrowed vocabulary of all kinds) seems to present a serious challenge to such delicately poised systems.

(Random funny example: Mandarin tàitai 'wife/married woman' and borrowed Taiwanese thài-thài (id.) sound very similar — but the phonetic tone profile is due in the first case to the "trochaic" stress of Mandarin leaving a "neutral tone" on the second syllable, while in Taiwanese the word is interpreted as if its own "iambic" stress had left a "light" Tone 3 [= high falling] on the first syllable.)

Chris Button said,

April 14, 2024 @ 1:07 pm

On tone sandhi, Anne Yue-Hashimoto's (1986) article on tonal flip flop in Chinese dialects includes the interesting proposal that the sandhi forms sometimes reflect the earlier values. I've seen some evidence for that elsewhere in Tibeto-Burman languages too.

FM said,

April 14, 2024 @ 2:00 pm

Intonational focus is found in French, but not every syntactic position or morphological marker may receive it.

Which is why the French translation of Darth Vader’s ‘I am your father’ as « Je suis ton père » does not convey the same meaning, as I explain here (in French):

https://prendrelangue.fr/2024/04/07/focus-luke-focus/

Chris Button said,

April 14, 2024 @ 3:17 pm

@ FM

Thank you so much for sharing. What a great article, and a great way to make a point.

"Mais ça aurait été sans compter sur la synchronisation labiale, j’imagine"

So joking aside, it remains a curious choice then. Your idea that it was done based on the written text rather than the original audio seems likely to me.

David Marjanović said,

April 14, 2024 @ 4:02 pm

Contrastive stress, other than corrective stress, seems to be absent in French. "Open from 9 am to 1 pm" would be stressed on the numbers, the contrasting information, in English or German, but in French – like in other Romance or Slavic languages at the very least – it goes de neuf [ˌ]heures à treize [ˈ]heures.

Jarek Weckwerth said,

April 14, 2024 @ 4:57 pm

@ David Marjanović: like in other Romance or Slavic I'll have to disagree. Polish at least would certainly have od (godziny) dzie[ˌ]wiątej do (godziny) trzy[ˈ]nastej even if godziny is present (and usually it won't be).

Julian said,

April 14, 2024 @ 6:34 pm

"But I accept that some things that English speakers are happy to do with intonation are really impossible in French, for example focusing or contrasting prepositions or verbal auxiliaries: "It's *under* the box (not *top* of it)"; "It *was* there (but now it's gone)".

"T'as vu mon sac?"

"Il est sur la table."

" Non, ______________________, mais Il n'est plus la."

What words could fill the gap to express "it *was* there" without using contrastive stress? Just curious

Coby said,

April 14, 2024 @ 10:10 pm

As I wrote in my previous comment: il y était bien…

FM said,

April 14, 2024 @ 11:02 pm

@Julian, Coby

In actual fact, intonational contrastive focus on prepositions in French is possible:

— Tu as vu mon sac ? Il était sur la table.

— Il est sous la table, pas dessus.

It also works with verbs for focusing on tense:

— Il est sur la table.

— Non, il était là, mais il n'y est plus.

One area where it does not work as well (if at all) is clitics:

— Regarde, Jules a rangé sa chambre.

— ?Non, je l'ai fait → Non, c'est moi qui l'ai fait.

— Jules a donné les clefs à Pauline.

— ?Non, il me les a données → Non, c'est à moi qu'il les a données.

Mark Liberman said,

April 15, 2024 @ 7:00 am

@FM: "In actual fact, intonational contrastive focus on prepositions in French is possible"

Thanks for the correction!

Jonathan Smith said,

April 16, 2024 @ 1:52 pm

re: Mandarin, contrastive focus exists but certainly feels more restricted than is the case in English. "IN (not on) the car," etc., won't work for "clitic" postpositions like -li 'inside'; here one would (alongside stress) call on syntax where the postposition is an independent nominal (che1 [de] LI3MIAN4*). "*I* am your father" etc. are also less likely — in such cases Mandarin likes its "conjunctive adverbs" (?) jiu4 and cai2. Thus "A: Is Mr. Li around? B: *I* am Mr. Li" = "Wo3 jiu4 shi4 [Li3 xian1sheng]", etc. Perhaps "wo3" here is also "stressed" but the syntactic device feels fundamental.

Taiwanese etc. have unique recourse to "citation tones" for stress, but IDK if such is alone OK to supply contrastive focus in cases like the above…

Re: sandhi tones as "original", sure — a better way to think about it is that one could in theory use internal reconstruction across "sandhi" and "citation" values to consider historical tones… if only some reconstructive principle were known for comparative tone outside of "a bunch of these daughter values are X, I guess the proto-value was X?" :D

Chris Button said,

April 17, 2024 @ 12:03 pm

You look at what triggered the tonal reflex and then consider options. While there is still bound to be variation, some contours or pitches may be restricted to certain tone categories based on historical provenance and individual conditioning environments in daughter languages.

Jonathan Smith said,

April 18, 2024 @ 7:03 am

No that's not the issue — "[d]espite longstanding attention to tonogenesis, what remains less studied and more poorly understood is how tone changes after it is well established in a language or language family" (Dockum 2019: 2). But by all means see what you think of Dockum's etc. proposals re: Tai and add your own insights…

Chris Button said,

April 18, 2024 @ 11:44 am

"Less studied and more poorly understood" is a reasonable position. But that statement does not deny the usefulness of the few studies on differences in attested variations across established tone categories. Gordon Luce, Alfons Weidert …