Queue

« previous post | next post »

This is an odd-looking word that I encounter fairly frequently, especially in my publishing ventures. Since I don't understand how / why "queue" should be pronounced like "cue", which is also a variant spelling for the same word, I'm especially cautious about "queue" when I approach it. Moreover, since I'm steeped in pinyin, I'm tempted to pronounce "queue" as "chyueyue" (!). Consequently, I always have to slow down when I spell / type it: "q-u-e-u-e", which I seldom have to do with other words except "Cincinnati", which I still haven't mastered.

Other than "its / it's", "queue" is probably the most frequently misspelled word I know of, even among educated persons.

I also am somewhat perplexed why "queue" means both "line" and "tail".

The word "queue" is used to mean a line, particularly in British English, because of its etymological origins. "Queue" comes from the French word "queue," meaning "tail," which in turn comes from the Latin word "cauda," also meaning "tail". This connection to "tail" makes sense when visualizing a line of people or objects, as they often form a linear arrangement reminiscent of a tail. The term "queue" is also used in computing to refer to a data structure where items are processed in a first-in, first-out (FIFO) manner, similar to how people are served in a line.

(AIO)

Phonologically, the leap from Latin cauda through Old French and Anglo-Norman to Middle English queue is a bit of a mystery to me as well:

From Middle English queue, quew, qwew, couwe, from Anglo-Norman queue, keu and Old French cöe, cue, coe (“tail”), from Vulgar Latin cōda, from Latin cauda. See also Middle French queu, cueue. Doublet of coda and cola.

Going backward further into the mists of prehistory:

From Proto-Italic *kaudā (“tail”), perhaps from Proto-Indo-European *keh₂u-d-eh₂ (“cleaved, separate”), from *keh₂w-. Compare cūdō (“to beat, hammer”), caudex (“tree trunk, stump”), Lithuanian kuodas (“tuft”).

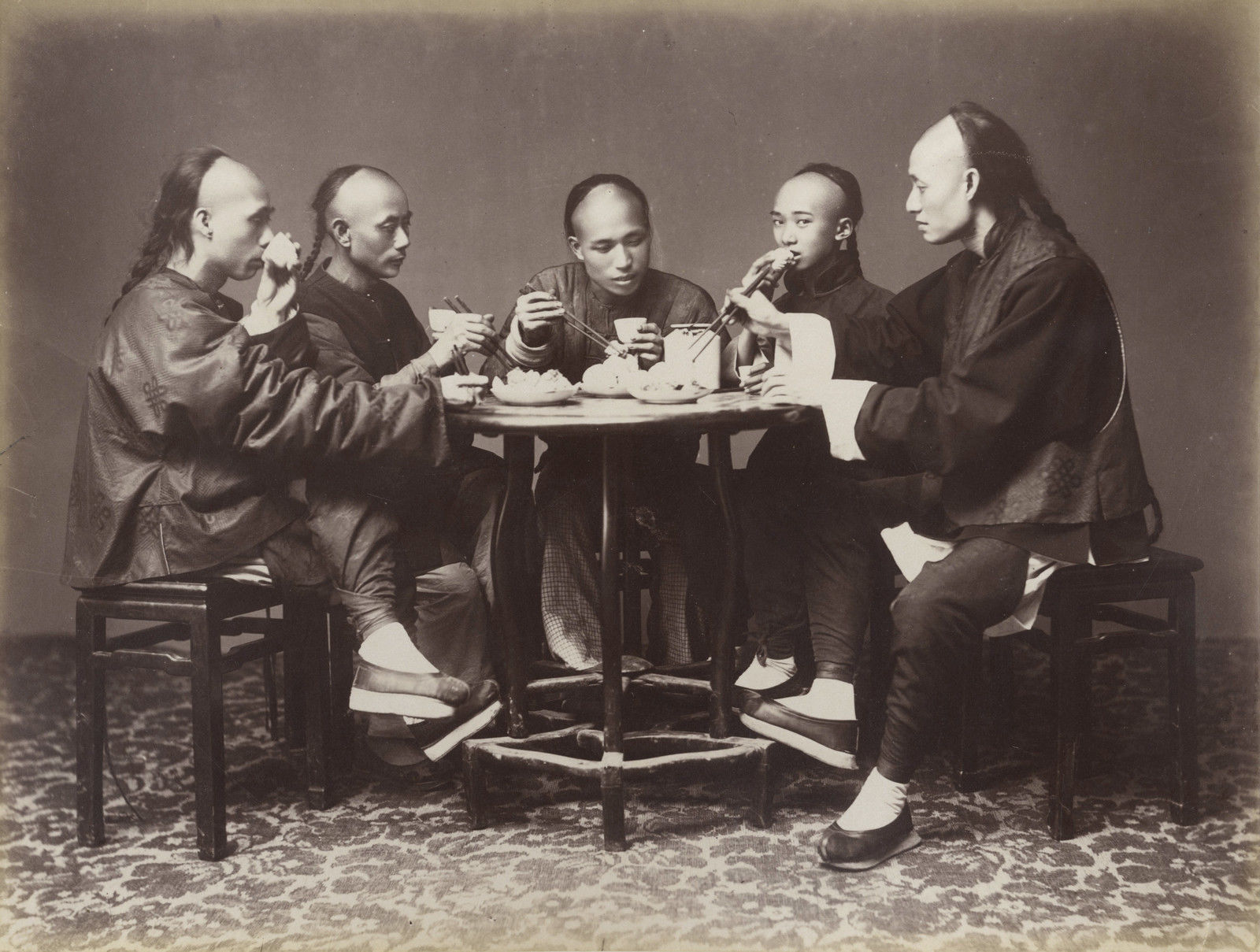

As a Sinologist, there's another meaning for "queue" that I often encounter, namely, the braid hanging from the back of the head that was imposed upon male Chinese by the Manchu government during the last dynasty, the Qing (pronounced "cheeng" [1644-1912]). Most Americans can see the etymological logic behind calling a single braid hanging from the back of the head a "tail", i.e., a "queue". Other than that, by and large Americans seem to be deeply puzzled by why Chinese immigrants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries wore their hair that way, what it symbolized, its history and status in China, and so forth. They are particularly puzzled by the fact that the braid at the back of the head was paired with the hair on the front half of the head being shaved bare down to the scalp:

Chinese men with queues, 1880s. Photo by Lai Afong (Wikipedia)

I summarized the concerns of American inquisitors about the Chinese queue in five questions as follows:

1. when was it imposed on the Han in China?

2. did the Han detest it at first?

3. what was the penalty for not wearing it?

4. did they come to terms with it later on and actually take it as a mark of their ethnicity?

5. when did they resist it and start to cut it off?

I posed these questions to two prominent Qing historians (both were undergrads at Swarthmore College, though ten years apart) who kindly weighed in thus:

From Pamela Crossley:

The queue was the traditional hairstyle of the Jurchens (and the Mongols had something similar, and before them the Khitans, Xianbei, Xiongnu, etc.)*. In the days of Nurgaci (1559-1626) the queue was required of all his followers because he wanted everybody to dress alike and have the same hairstyle, his idea of “one family.” When the Qing moved into Liaodong, where they first experienced a huge Chinese population, Hong Taiji (1592-1643) let the Chinese wear their hair any way they wanted. But when the Qing got to Beijing, Dorgon (1612-1650) imposed the queue again. He changed the policy for a short time to try to allay resistance, but the Manchu aristocracy insisted it be imposed again (partly for political reasons and partly because they thought Ming (the previous dynasty) hair was effeminate). By then it was clear to the Qing leadership that the Chinese did not regard the queue as a symbol of inclusion, but as a symbol of subjugation. The Qing then changed their view to agree with the Chinese, and imposed harsh penalties for anybody who refused to wear the queue.

*[VHM: When I was doing archeological work in China and Central Asia during the 80s, 90s, 00s, and 10s, if I came upon some smashed statues from medieval times and I wanted to know their ethnicity, I would turn them over and look at the number of braids splayed across their back. if there were 7, I knew they were Turkic.]

What was the penalty for not wearing it? I’m not sure this was specified, as much else with Chinese law, it was a matter of context. In the early Qing years, not everybody knew they were supposed to wear the queue, and Qing changes in policy created some confusion. Those who were not wearing queues because they didn’t know they were supposed to were probably given a light punishment, if any, and sent to the barber. But those who refused to wear the queue as a symbol of resistance to Qing rule were dealt with harshly—anything from penal servitude to beheading if they were clearly rebellious.

It is possible that Chinese officials and literati considered the queue a sign of loyalty to the Qing regime and by extension to Chinese classical civilization at the time of the Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864). The policy of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom was the opposite—those who wore queues and refused to grow their hair were dealt with harshly. But by after the Taiping War the queue and the gown were kind of linked together, is my impression. You either showed you were a progressive by wearing European dress and growing out the front of your hair or you stuck wit traditional dress, queue and all. After the Treaty of Shimonoseki (April 17, 1895), European dress and hairstyles were associated with nationalism of the Sun Yat-sen (1866-1925) and Liang Qichao (1873-1929) style. But plenty of nationalists—and diehard monarchists—wore traditional dress, perhaps with a silk cap that obscured whether they had queues (that is, shaved hair in front) or not. And there were nationalists in the Zhang Taiyan (1869-1936) style who deliberately wore long hair resembling the Ming (with traditional robes) on the assumption that this was a “traditional” Chinese hairstyle before barbarian invasion.

One way or another, queue wearing was a sign of affiliation—in Qing eyes, willing and inclusive in the earliest phase, in Chinese eyes, unwilling and demeaning

As for Chinese in the United States, was the queue a sign of “ethnicity”? Chinese workers were sojourners, and expected to return to China, perhaps repeatedly. Getting caught alighting at the docks with a foreign hairstyle would not necessarily be an advantage. Many workers were from very traditional villages where people just thought of the queue as conventional, without regard to its history. I think it is possible that given the prejudices in America many Chinese workers might have kept the queue as a sign of pride. But many Chinese in America were not workers, and came as professionals, students, merchants, often from treaty port families, and they would have by habit dressed in European clothing and worn short hair grown out in front.

The queue, as you know, is a character in folklore, and—ironically—as the shénbiàn 神辫 ("divine / supernatural braid")–a weapon of the weak against the oppressors, like kungfu (a type of Chinese martial arts).

Also, some Chinese probably wore the queue for hygiene reasons (to avoid ringworm, lice, etc.). Period photos seem to show a good deal of shaved headedness among Chinese workers; it could be something they picked up shipboard.

From Matthew Sommer:

For your questions 1-3 (above), you should check chapter 3 of Kuhn’s Soulstealers — the answers are all there. You might also check Wakeman’s Great Enterprise, where he characterizes the imposition of the tonsure (i.e. shaving of the front of the head) as a symbolic castration for elite Ming men.

For the others, here are my “seat of the pants” answers:

4. Yes, by the end of the 17th c. the tonsure/queue was universal among Han Chinese men and I think it’s safe to say that everyone was used to it. My guess is that the last to submit were probably Han Chinese subjects of the Zheng Chenggong (1624-1662) regime in Taiwan, which the Qing conquered in 1683. After that, it became the most obvious gender cue marking a person visually as a man. Within China, I doubt it was experienced as an ethnic marker per se (b/c bannermen also wore the queue, as did the Hui [Muslim]), but on the frontiers it probably played that role (as did footbinding to some extent — see Melissa Brown re Taiwan), and certainly for overseas Chinese it was a very clear marker of Chineseness. The queue featured prominently in racist caricatures of Chinese in Western political cartoons after the Opium War.

5. Not sure of an exact date, but in the early days it was refusal to shave the front of the head that signalled loyalty to the Ming and resistance to the Qing; by the 18th c., when all Han men wore the tonsure/queue, it was cutting off the queue that took on symbolic significance (this may have begun as early as the 三番 rebellion (Revolt of the Three Feudatories (1673-1681]), but I am not sure). When rebels declared against the Qing, the first thing they did was to cut off their queues. They also stopped shaving the front of the head (hence the Taiping Rebels were known colloquially as the “long-haired” or “hairy” rebels). In 1911, the rebellious armies stationed soldiers at crossroads and city gates and forcibly cut off the queues of all men who passed by.

For the historical facts about the queue (called "biànzǐ辮子" ["braid"] in Mandarin), see Endymion Wilkinson's encyclopedic Chinese History: A New Manual, where his ideas on most of the questions that I raised above are in the 6th edition (Section 11.3). In the 7th edition he has added a line in Box 82 on Xiongnu hairstyles (they wore queues).

Finally, there is the concept of "fake foreign devil" . I remember from my reading of Chinese literature from the 20s and 30s when China was governed by the Republic of China that i often encountered this term in novels and essays where the author was describing "jiǎ yánɡɡuǐzi 假洋鬼子" who were trying to appear modern and Western. They would coil their queue up on top of their head and cover it with a cap. They were unwilling to take the drastic step of cutting off their queue because they might need it in other circumstances where they wanted to show that they were "real Chinese". Of course, there were also individuals during this period who held dramatic queue-cutting ceremonies to demonstrate that they were no longer beholden to the defunct Qing dynasty and old-fashioned ways.

One more fun note

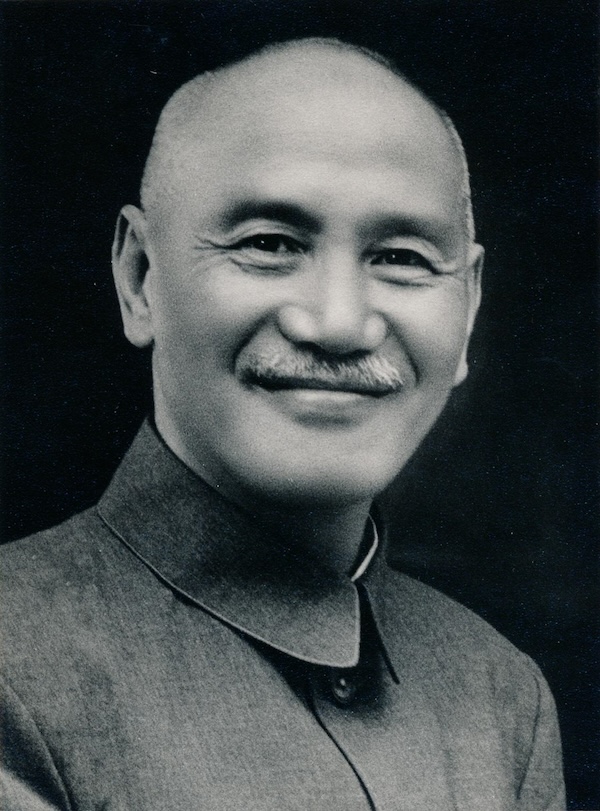

Multiple sources describe Chiang Kai-shek (1887-1975) as having a shaved or shaven pate. One source characterizes his appearance as "monklike face with its severe cropped mustache and his shaven pate". Another mentions his "shaved head and moustache gave him a look of grim determination". Some sources mention he cut off his queue (braid) in 1905, according to Chinese History for Teachers and Kids encyclopedia facts.

It appears Chiang Kai-shek's baldness was a result of a purposeful shaving, possibly influenced by a "monk thing", rather than being naturally bald.

(AIO)

I think he was motivated by: 1. anti-Manchu sentiments; 2. the desire to appear modern

When I taught at Tunghai University in Taichung, Taiwan from 1970-72, Chiang Kai-shek (1887-1975) was still alive. I remember that, if a male student had hair that hung down over his ears, he would be marched to the police station and be given a buzz cut. Similarly, if a girl's skirt showed her knees, she would be penalized (or receive a bad mark on her record).

Photograph of President Chiang presented by him to President Truman. (Truman Library)

Selected readings

- "Stand in / on line" (2/1/25) — the vagaries of "form a queue" vs. "stand / get in line"

- "Obama and the end of the queue" (4/24/16) — includes 49 occurrences of "queue" in the Wall Street Journal 1987-1989 corpus

- "Mixed metaphor of the week" (11/29/16) — the comments include a hyper sophisticated discussion over whether queueing can have fewer than 2 elements, a asdfasdasdf over the difference between "cue" and "queue", a quandary over whether "queue" is the only English word that has five consecutive vowels, and the "fun fact" that "queue" is the only word in English that sounds the same if you delete the last four letters

- "Triple topolectal reprimand" (5/29/16) — jumping the queue // cutting in line

[h.t. Barbara Phillips Long; thanks to Joshua Fogel]

ajay said,

July 24, 2025 @ 11:15 am

I don't understand how / why "queue" should be pronounced like "cue", which is also a variant spelling for the same word

This brought me up short. The same word? There's a word which can be spelled either "queue" or "cue" and have the same meaning – like "labour/labor" or "gaol/jail"?

Queue, to me, means either a line of people or a long pigtail of hair worn by Qing Chinese (and indeed 18th century British soldiers) – both derived fairly obviously from a word meaning "tail".

"Cue" is either the stick you hit billiard balls with, or one of several closely related meanings to do with a signal for an actor to start doing something.

What's the word that can be spelled both "queue" and "cue"?

(Incidentally, the idea that a group of people ordering themselves behind something is a bit like a tail gives us not only "queue", but also the phrase "fighting tail" – a Scots phrase meaning "a group of armed followers of a chieftain". Your fighting tail is your warband, your raiding party, or whatever. )

Coby said,

July 24, 2025 @ 12:24 pm

What baffles me is that some people spell barbecue as "barbeque" and somehow expect the final -que pronounced the same as cue, when the combination que itself needs another -ue to be so pronounced. (I think this stems from confusion with the playful spelling Bar-B-Q.)

I remember being similarly baffled some 50 years ago when one of the terrorists who kidnapped Patti Hearst called himself Cinque, to be pronounced like "sinkew".

JMGN said,

July 24, 2025 @ 2:19 pm

The name of the leter Q is "cue".

According to Garner and Fowler, the inflected verbal form is "queu·ing" (LPD's /ˈkjuːɪŋ/); othwerwise, "queueing" would be the only common word in the English language with five consecutive vowels (cf. cooeeing, miaoued, miaouing, zoaeae, Aeaean, and Rousseauian).

According to Brooks's Dictionary of the British English Spelling System, as a trigraph spelling only /k/ (not /kw/ plus vowel) occurs word-initially only in queue and medially only in milquetoast (where it is nevertheless stem-final in a compound word); ; otherwise only word-finally and only in about 18 words mainly of French origin. In word-final position in monosyllables appears to be regular (exceptions: ewe; cue, hue, queue).

Even where the preceding vowel letter is some words can retain or drop the before , e.g. cuing/cueing, queuing/queueing, but most other words with always drop it, e.g. arguing, burlesquing, issuing, rescued, subdued, suing, valued.

JMGN said,

July 24, 2025 @ 2:47 pm

Sorry for all the mising words in my previous post. Here's a revised one:

According to Garner and Fowler, the inflected verbal form is "queu·ing" (LPD's /ˈkjuːɪŋ/); othwerwise, queueing would be the only common word in the English language with five consecutive vowels (cf. cooeeing, miaoued, miaouing, zoaeae, Aeaean, and Rousseauian).

According to Brooks's Dictionary of the British English Spelling System, as a trigraph spelling only /k/ (not /kw/ plus vowel), occurs word-initially only in queue (and medially only in the dated insult milquetoast, where it is nevertheless stem-final in a compound word); otherwise only word-finally and only in about 18 words, mainly of French origin. In word-final position in monosyllables appears to be regular (exceptions: ewe; cue, hue, queue).

Even where the preceding vowel letter is some words can retain or drop the before , e.g. cueing, queu(e)ing, but most other words with always drop it, e.g. arguing, burlesquing, issuing, rescued, subdued, suing, valued.

The name of the leter Q is "cue" (hence "barbeque, bar-b-cue, bar-b-que, BBQ").

Allen W. Thrasher said,

July 24, 2025 @ 3:12 pm

I can’t remember where I read it, but I read somewhere an account by a Chinese in 19th c. USA, that he and some of his friends —probably students—removed their queues but had caps to which queues were attached to put on when they were visited by men from the consular offices, which kept track of such things. If the government knew they’d removed them, maybe it would do something bad to them when they went back home.

Lars said,

July 24, 2025 @ 3:39 pm

Re cue versus queue, the Danish words are spelled identically. There's a line from a rap song that goes:

" De står i kø med hver sin kø for at få nogen klø

Når jeg har vundet et par gange så er det adjø "

A guy walks into a bar and muses about how he plays pool against other people. The last word is French, obviously.

Jarek Weckwerth said,

July 24, 2025 @ 4:21 pm

I'm tempted to pronounce "queue" as "chyueyue" — So what would that pronunciation be? I'm afraid I can't decode it at all.

Tom said,

July 24, 2025 @ 4:24 pm

I'm pretty sure Chiang Kai-Shek had real male pattern baldness. You can see his hairline.

Also, post has two is's in second paragraph.

Yves Rehbein said,

July 24, 2025 @ 4:55 pm

@ Tom, I stumbled on that as well but its correct.

John from Cincinnati said,

July 24, 2025 @ 6:57 pm

Albuquerque

Peter Vanderwaart said,

July 24, 2025 @ 7:18 pm

Data point: Josephine Tey titled a book "The Man In The Queue" in 1929.

Pamela said,

July 24, 2025 @ 7:57 pm

Thanks for correcting my "Hung Taiji" to "Hong Taiji," but I never use that. "Hong Taiji" is indistinguishable between Manchu Xongtayiji ᡥᠣᠩᡨᠠᡳᠵ and Chinese 洪台極. Representing one or the other precisely (which is impossible, since in transliteration they are the same) doesn't seem important to me. "Hong Taiji" is most often corrupted in Chinese records (as in the 清史稿) as 皇太極, which is interesting only as a corruption, and Xongtayiji in Manchu in probably inspired by Mongolian Khongtayiji, which is also not represented in Manchu transcription. What seems important to me is whether or not the writer is referring to the Manchu or the Chinese appelation, and whether this is legible to the reader. "Hung Taiji" already as a venerable legitimacy through Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period (though it mistakenly gives Abahai as his name). That is, to my mind, the best way to make clear to the reader that the name being referred to is Manchu, not Chinese. An attempt to be precious in transliteration (which is not an objective phenomenon) seems to me much less valuable than clarifying whether a Manchu or Chinese term is being indicated. Thus, my "Hung Taiji." This is how he will appear in my forthcoming history of the Qing.

Joshua K. said,

July 24, 2025 @ 10:06 pm

"Queue" might be the only word in the English language for which one could remove 80% of the letters and it would still be pronounced the same way.

Marttin Schwartz said,

July 25, 2025 @ 1:11 am

The queue is the tail beneath the head of a Q.

rosie said,

July 25, 2025 @ 2:07 am

"Queue" doesn't have a trigraph "que", it has a digraph "qu" pronounced /k/, then "eu" pronounced /ju/ (as in "neutral") then a silent "e". So analogues may have a vowel other than e after the qu, e.g. piquant and quinoa.

Matthew J. McIrvin said,

July 25, 2025 @ 3:00 am

Many French words end in "que" with the vowels silent, so the use of "ueue" here probably functions to indicate that it is pronounced (much like "eu" in the middle of a word, so maybe Rosie's breakdown is correct).

JMGN said,

July 25, 2025 @ 3:02 am

According to Brooks's "Dictionary of the British English Spelling System", as a digraph spelling only /k/ (not /kw/), occurs initially or medially (never finally) in about 50 words mainly of French origin, such as "piquant" (LPD's /ˈpiːkənt/).

ajay said,

July 25, 2025 @ 3:48 am

The name of the letter Q is "cue".

This is positively Carrollian. Surely the name of the letter Q is, well, Q?

“The name of the song is called "HADDOCKS' EYES."' 'Oh, that's the name of the song, is it?' Alice said, trying to feel interested. 'No, you don't understand,' the Knight said, looking a little vexed. 'That's what the name is CALLED. The name really IS "THE AGED AGED MAN."' 'Then I ought to have said "That's what the SONG is called"?' Alice corrected herself. 'No, you oughtn't: that's quite another thing! The SONG is called "WAYS AND MEANS": but that's only what it's CALLED, you know!' 'Well, what IS the song, then?' said Alice, who was by this time completely bewildered. 'I was coming to that,' the Knight said. 'The song really IS "A-SITTING ON A GATE": and the tune's my own invention.”

JMGN said,

July 25, 2025 @ 4:00 am

The name of the leter Q is "cue" http://web.archive.org/web/20200712141733/https://www.oed.com/oed2/00055418

See Q : http://web.archive.org/web/20200713022226/https://www.oed.com/oed2/00193868

Hence "barbeque, bar-b-cue, bar-b-que, BBQ".

Michael Vnuk said,

July 25, 2025 @ 6:23 am

Victor Mair writes: 'Other than "its / it's", "queue" is probably the most frequently misspelled word I know of, even among educated persons.'

I don't recall seeing 'queue' misspelled. Words I have noticed frequently misspelled, even among educated persons, are 'led' (as 'lead'), 'supersede' (as 'supercede' etc) and 'misspell' (as 'mispell'). But these are only my impressions.

Chris Button said,

July 25, 2025 @ 6:36 am

My hunch is that the use of "queue" in modern computing popularized the word in North American English. Until then, "cue" (as in the stick) was probably as close as things usually came.

Victor Mair said,

July 25, 2025 @ 6:51 am

@Pamela

Thank you for setting the record straight about "Hung Taiji".

JMGN said,

July 25, 2025 @ 6:52 am

@Vnuk

Relatedly, according to a blog article by Steven Norman under the title “My 100 most mispronounced words in English”, the word "depends" should be /dɪˈpenz/ when “correctly” pronounced.

https://clil.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/02/100misproounced-words.pdf

In contrast, the OED disagrees features /dɪˈpɛnd/ as the base form of the verb, rhyming with amends /əˈmɛndz/.

Yet, Kenyon and Knott show both versions of amends, with /əˈmɛndz/ first and /əˈmɛnz/ second. Merriam-Webster similarly shows the /d/ as optional with \ə-ˈmen(d)z\.

Is the loss of phonemic /d/ in the coda of "depends" lexicalized?

Victor Mair said,

July 25, 2025 @ 6:58 am

Talking about difficult / opaque spellings and pronunciations, I found that the author of this long comment to the "Memes, typos, and vernacular English in a 12th-century Latin homily" post hails from Ocooch Mountains, "a place name for the Western Upland area of Wisconsin also known as the Driftless Region, meaning un-glaciated, lacking glacial drift…". The composition and shape of that name (half of its six letters are "o") threw me for a loop (I couldn't figure out from its spelling how to pronounce it, so I looked up its etymology:

=====

The vowels and consonants of Ocooch and their order are correct for the Ioway language, a Siouan language. The Ho Chunk, a related Native American tribe, called them a name phonetically similar to Ocooch, waxoj, pronounced WAH-KOH-CH(e). The Ioway-Otoe-Missouria emerged from the Oneota cultural group in western Wisconsin. Evidence of their presence is found throughout the Wisconsin Western Uplands as far north as Lake Pepin, and Red Wing, Minnesota,* over to Effigy Mounds National Monument, the Upper Iowa River, and La Crosse, Wisconsin dated from AD 900 to 1700. Decimated by epidemics, the Ioway left the area after the Otoe-Missouria and as the Algonquin language-speaking Sauk, Meskwaki and Kickapoo peoples came from Michigan fleeing the Iroquois as a result of the French and Indian Wars, or Beaver Wars. Ocooch Mountains written in current Ioway tribal orthography "Paxochi Ahema'shi," pronounced as PAH-ko-chee ah-hay-MAH-shee” means "Mountains of Snowy Lodges." In addition, the phonetically similar Ho Chunk name for the Baraboo and Trempealeau rivers was Hoguc (Ho gooch), or Hocooch, "Spear Fishing Waters".

(Wikipedia)

=====

*Over the years, I have purchased many excellent shoes, boots, and socks from Red Wing Shoes, located here.

David Morris said,

July 25, 2025 @ 7:42 am

Some time ago I mentioned on Facebook that I'd spent a long time on hold while calling a 'help' line, while a recorded voice told me that I was now [number]th in the queue. A Facebook friend commented and used the spelling que in an otherwise perfectly spelled comment. I asked her about this, and she wrote “I tend to use que as a shortcut for queue online. I don’t know why, either. I’m usually extremely picky about spelling.”

Barbara Phillips Long said,

July 25, 2025 @ 7:59 am

I was intrigued by ajay's comment about fighting tails in Scotland.

The comment brought to mind a passage in Alinor, a historical novel by Roberta Gellis that is the second book in her series the Roselynde Chronicles. In it, the widowed Alinor is discussing with Ian, the man who would like to be her next husband, the disposition of property, since Alinor holds the Roselynde Keep property (yes, a legal anomaly in England, but a key part of the fictional Roselynde's history). By the 18th century, such a discussion would result in the drawing up of marriage "settlements," but that term is not used in the novel. The story is set while John "Lackland" was king of England (reigned 1199-1216):

– – –

"Terms?" She was impatient, feeling that he was trying to draw her away from a more important issue. "I suppose the same terms upon which I took Simon. Yours to you, mine to me, during life. Your lands to be left in male tail–unless you wish to set something aside for a daughter, but that is not necessary. I have enough to dower any girls…"

– – –

The result of this agreement would have been to entail the husband's estate, which would be inherited by the oldest living male directly descended from him. Fans of Downton Abbey might also recognize the term, which enabled ongoing plot complications in the show. An explanation of the law and how the show uses it by J.B. Ruhl of Vanderbilt University Law School is here (along with numerous plot spoilers):

https://www.vanderbilt.edu/lawreview-new/wp-content/uploads/sites/278/2015/04/The-Tale-of-the-Fee-Tail-in-Downton-Abbey.pdf

It turns out there are a lot of "tail" terms in English law, and I am no expert on that subject. Various sources have listed the following terms:

entail

fee tail

fee tail male

fighting tail

tail general

tail male

tail special

tailzie

tenancy in tail

Wiktionary has a couple of etymologies for entail:

Etymology 1

From Middle English entaillen, from Old French entaillier, entailler (“to notch”, literally “to cut in”); from prefix en- + tailler (“to cut”), from Late Latin taliare, from Latin talea. Compare late Latin feudum talliatum (“a fee entailed, i.e., curtailed or limited”).

Etymology 2

From Middle English entaille (“carving”), from Old French entaille (“incision”), from the verb entailler. See above.

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/entail

Oxford has an online reference site that sources information from the Oxford University Press publications. This is some information on tail male that comes from A Dictionary of Law:

"An entailed interest under which only male descendants of the original tenant in tail can succeed to the land. If the male line dies out, the land goes to the person next entitled in remainder or in reversion. The interest may be general or special see tail general; tail special."

https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803101916712

Wikipedia says:

The terms fee tail and tailzie are from Medieval Latin feodum talliatum, which means "cut(-short) fee". Fee tail deeds are in contrast to "fee simple" deeds, possessors of which have an unrestricted title to the property, and are empowered to bequeath or dispose of it as they wish (although it may be subject to the allodial title of a monarch or of a governing body with the power of eminent domain). Equivalent legal concepts exist or formerly existed in many other European countries and elsewhere; in Scots law tailzie was codified in the Entail Act 1685.

Most common law jurisdictions have abolished fee tails or greatly restricted their use. They survive in limited form in England and Wales, but have been abolished in Scotland, Ireland, and all but four states of the United States.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fee_tail

The Downton Abbey article listed above has more background:

The first episode of Downton Abbey opens in 1912 England. Robert’s great-great-grandfather took title to the estate in fee tail male, which, based on the number of generations we can estimate, occurred sometime in the early 1700s. However, the fee tail in its early forms dates at least as far back as the late 1100s—providing a rich history of similar property transfers leading up to the Crawleys’ predicament.

By far the most comprehensive treatment of that history is Joseph Biancalana’s The Fee Tail and the Common Recovery in Medieval England 1176–1502. Some brief details—just enough to get what’s going on in Downton Abbey—are illuminating. It all started with maritagium, which was a grant of land made by a woman’s father or other relative upon her marriage. The grant was to the woman and her husband, but the land was inheritable only by the woman’s children with that man; if she had none, upon her death the land would revert to the grantor or his assigns or heirs. The social purpose was to provide inheritance to women in an era of male primogeniture, to help the new couple get a start, and to bond the two families. …

Today, the only [U.S.] remnant of the fee tail is the "tenancy in tail” in Delaware, Maine, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island. …

Besides serving as a plot twist for good period fiction [48] and as a juicy hypothetical harnessed by law professors teaching property, the fee tail has no relevance in modern England or the United States.

48. The fee tail also plays a prominent role in such great works as Pride & Prejudice by Jane Austen, Middlemarch by George Eliot, and Brideshead Revisited by Robert Louis Stevenson. [sic — Evelyn Waugh].

https://www.vanderbilt.edu/lawreview-new/wp-content/uploads/sites/278/2015/04/The-Tale-of-the-Fee-Tail-in-Downton-Abbey.pdf

For more on the history of the entail and on its use in Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice, see this publication by the Jane Austen Society of North America. The author discusses the legal difference between holding the land and owning the land. There's also a brief explanation of the origin of the term tail. The word derived from French, and the article notes that William the Conqueror's successful invasion of England in 1066 led to significant changes in property law:

The term comes from the French word tailler, meaning “to carve,” and perhaps refers to the fact that the estate was carved exactly as the grantor wished it to be. It was created by language in a will or deed reading: “To A and the heirs of his body.” This was a fee tail general; it limited inheritance to A’s biological heirs, cutting off collateral heirs such as nieces and nephews. The fee tail male limited passage to the male line: “To A and the heirs male of his body.” A further limitation, called a fee tail special, was also possible: “To A and the heirs male of his body by his wife, Z.” This cut off any children by subsequent wives.

https://www.jasna.org/persuasions/printed/number11/redmond.htm

The University of Nottingham has an explanation of terms having to do with settlements. It includes more information about tail general:

The most usual fee tail was 'tail male'. This limited the descent to the legitimate male heirs 'of the body' of the owner, i.e. sons and grandsons of the owner's marriage.

'Tail general' was similar, but included females. However, males would still take precedence over females. That meant that a younger son would inherit before an elder daughter. This type of fee tail is the one used today by our Royal Family. The daughters of Prince Andrew (born 1960) are higher up the line of succession than the son and daughter of Princess Anne (born 1950).

https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/manuscriptsandspecialcollections/researchguidance/deedsindepth/settlements/terms.aspx

Research into "fighting tails" was not as successful as poking around in the history of entails. Search engines were convinced I wanted "fighting tales," but one source of information is The Clans, Septs, and Regiments of the Scottish Highlands, by Frank Adam. It looks like it was published in 1908, but the book is now in at least its eighth edition.

JMGN said,

July 25, 2025 @ 8:28 am

@rosie

According to the CGEL, "through" contains three symbols: composite th + simple r + composite ough (/θ/, /r/, /u/, respectively). Thus, Y is a vowel in fully (/i/), a consonant in yes (/j/), and part of a composite vowel symbol in boy (/ɔi/).

Peter B. Golden said,

July 25, 2025 @ 9:20 am

Regarding the partially shaved head and queue hairstyle noted among Mongols, Jurchens, Khitans, Xianbei, Xiongnu, Byzantine authors note a similar hairstyle in descriptions of the Kyivan Rus' ruler, Sviatoslav (r. 962-972), who took it from his steppe neighbors (presumably the Pechenegs, who ultimately killed him). This hairstyle adopted by the later Ukrainian Cossacks (depicted in Russian paintings) is called by a number of names: chub (чуб) – and variants, khokhol (хохол), and others. Khоkhоl is also a somewhat derogatory Russian term for Ukrainians. Steppe influences among the Cossacks (Ukrainian, Don and others) can be seen in titles, ranks etc.

Rodger C said,

July 25, 2025 @ 9:47 am

one of the terrorists who kidnapped Patti Hearst called himself Cinque, to be pronounced like "sinkew".

He named himself after a 19th-century slave rebellion leader from Senegal whose name I always pronounced "Sinkwee." The original, I believe, was Senkwe. Did the kidnapper actually mispronounce it? Not that I'd be surprised, with that crew.

JMGN said,

July 25, 2025 @ 11:07 am

@Rodger_C

Gontijo et al. (2003, in Brooks, G. 2015) do not recognise as a separate grapheme, but their calculations show that pronounced /k/ together constitute 9% of pronunciations of , and the other 91% of occurrences of are /kw/.

In linguistic terms it is unnecessary to analyse /kw/ as a single phonetic unit since in all words containing /kw/ (those where it is spelt , plus the oddities "acquaint, acquiesce, acquire, acquisitive, acquit" (in these five words /k/ is ), "awkward, coiffeur, coiffeuse, coiffure, cuisine, kwashiorkor, choir") the /k/ is spelt separately, as it is also in compounds like "backward".

Brooks, G. (2015). Dictionary of the British English spelling system. Open Book Publishers.

David Marjanović said,

July 25, 2025 @ 11:09 am

What rosie said: French qu, English eu (after all English lacks the sound of French eu), either e.

The billiard stick is in fact spelled queue outside of English; it really must be a tail etymologically. The other meanings of cue, in English, I've often seen spelled que on teh intarwebz.

Victor Mair said,

July 25, 2025 @ 12:40 pm

@Jarek Weckwerth

You have to learn to pronounce it according to the rules of pinyin, which is what I was talking about in that sentence.

Bob Ladd said,

July 25, 2025 @ 1:06 pm

@Chris Button: Your hunch that "queue" entered American English because of computer jargon is strongly borne out by Google n-grams. In British English, "in the queue" takes off sharply between 1920 and 1940 and then continues a steady rise until now. In American English, "in the queue" is hardly attested until about 1960, then steadily increases.

It's difficult to compare across the two corpora, but the percentage numbers on the y-axis of the n-gram plots suggest that it's still more prevalent in BrEng than in AmEng. Presumably this difference reflects all the occurrences of "in the queue" in BrEng that would be translated into AmEng as "in line", i.e. referring to a line/queue of people waiting for something. (Do New Yorkers still say "on line" in that sense? Or has that usage been forced out by the new sense of "online"?)

Gregory Kusnick said,

July 25, 2025 @ 2:01 pm

Just guessing here, but it seems to me a typical speaker of US English in the 1970s was more likely to encounter "in the queue" on Masterpiece Theater than in computer science journals.

Victor Mair said,

July 25, 2025 @ 10:29 pm

Fraom Alan Kennedy:

In France, line jumpers are reprimanded, and told to "faire la queue!"

Peter Taylor said,

July 26, 2025 @ 3:19 am

The OED lists both queuing and queueing. Pace Garner and Fowler, queueing is a common word in the English language. Less common, but also in the Scrabble Word List, are euouae (and plural) and forhooieing.

Jim S. said,

July 26, 2025 @ 12:28 pm

In the first two minutes of this Queueing Theory course

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AsTuNP0N7DU&list=PL59NBu6N8dUqYClaKpoozyzK3Kpcm5eou

Robert Cooper says that most people working in his technical field

prefer "queueing" over "queuing", as do most books and technical

papers, but that most people outside the field omit the second "e".

Jarek Weckwerth said,

July 27, 2025 @ 5:39 am

You have to learn to pronounce it according to the rules of pinyin, which is what I was talking about in that sentence.

OK, but which one am I supposed to read as pinyin? Queue or chyueyue? And if the former, what does the latter represent?

unekdoud said,

July 27, 2025 @ 5:57 am

In computing there's a term deque, short for double ended queue, pronounced deck. (Its plural is pronounced decks.)

DDeden said,

July 27, 2025 @ 10:27 pm

Victor, you mentioned my home turf, Red Wing. I had kin there tanning the leather (SB Foote) and making shoes (RW Shoe) and skates (Riedell, "rye-dell"). Spent a lot of time walleye fishing with my dad at Lake Pepin and along the Mississippi there.

Back growing up, I only knew the Ho Chunk as the Winnebago, the forest Sioux.

As a cue-riosity, any chance that queue-bearing Chinese ever stood in a queue at Kew Gardens?

Philip Taylor said,

July 28, 2025 @ 4:38 am

Well, undoubtedly pronounced by some (perhaps by many/most) as "deck" but not by me. I pronounce it "de-queue", where the leading "de" has the sound of the (name of the) river Dee, not the sound of French de.

Pedro said,

July 28, 2025 @ 4:29 pm

Rosie's explanation is perfect and succinct. The word is derived from Norman French by completely regular correspondences, and is pronounced exactly as we'd expect based on the original form and the modern French queue.

The real mystery is why we spell it "queue" instead of "kew". For some reason we've preserved (or restored?) the French spelling, and that's the source of the unusual relationship between spelling & pronunciation.

ajay said,

July 29, 2025 @ 10:08 am

Research into "fighting tails" was not as successful as poking around in the history of entails.

Citations could include Aytoun's famous poem about The Massacre of the McPherson:

FHAIRSHON swore a feud

Against the clan M’Tavish—

March’d into their land

To murder and to rafish;

For he did resolve

To extirpate the vipers,

With four-and-twenty men,

And five-and-thirty pipers.

But when that he had gone

Half-way down Strath-Canaan,

Of his fighting tail

Just three there were remainin’.

They were all he had

To back him in ta battle:

All the rest had gone

Off to drive ta cattle.

“Fery coot!” cried Fhairshon—

So my clan disgraced is;

Lads, we’ll need to fight

Pefore we touch ta peasties.

Here’s Mhic-Mac-Methusaleh

Coming wi’ his fassals—

Gillies seventy-three,

And sixty Dhuinéwassels!”

(the poem continues in increasingly silly vein. A gillie or ghillie is originally a servant, as in Gilchrist, servant of Christ; it subsequently became a stalking guide, from which "ghillie suit". A duniewassal is a nobleman. The aberrant spelling is to represent the Highland accent, which tends to avoid voicing voiced consonants, so "badly in need of a drink" becomes "patly in neet of a trink". There is no such place as Strathcanaan and no such person as Mhic-Mac-Methusaleh.)

ajay said,

July 29, 2025 @ 10:12 am

"The billiard stick is in fact spelled queue outside of English; it really must be a tail etymologically."

Very interesting. I notice that the etymology of "cue" as in an actor's signal to do something is uncertain. There is a strong temptation to assert that it originates with the habit of putting someone in the wings to prod the actors with a long stick when they've forgotten that it's their turn to speak, but this is almost certainly not true.