Real trends in word and sentence length

« previous post | next post »

A couple of days ago, The Telegraph quoted an actor and a television producer emitting typically brainless "Kids Today" plaints about how modern modes of communication, especially Twitter, are degrading the English language, so that "the sentence with more than one clause is a problem for us", and "words are getting shortened". I spent a few minutes fact-checking this foolishness, or at least the word-length bit of it — but some readers may have misinterpreted my post as arguing against the view that there are any on-going changes in English prose style.

So I wrote a script to harvest the inaugural addresses and state of the union addresses from the site of the American Presidency Project at UCSB, and some other scripts to (I hope) extract the texts of the speeches from their html wrappings, and to count word and sentence lengths. Why use these sources? Well, different kinds of writing have their own norms, and so it wouldn't be good evidence of an overall historical trend to show (for example) that 20th-century sports reporting is stylistically different from 19th-century sermons, or that 21st-century blogging is different from 18th-century pamphleteering. U.S. Presidential addresses are one accessible example of a body of texts, spanning more than 200 years, which ought to be fairly consistent in genre and register.

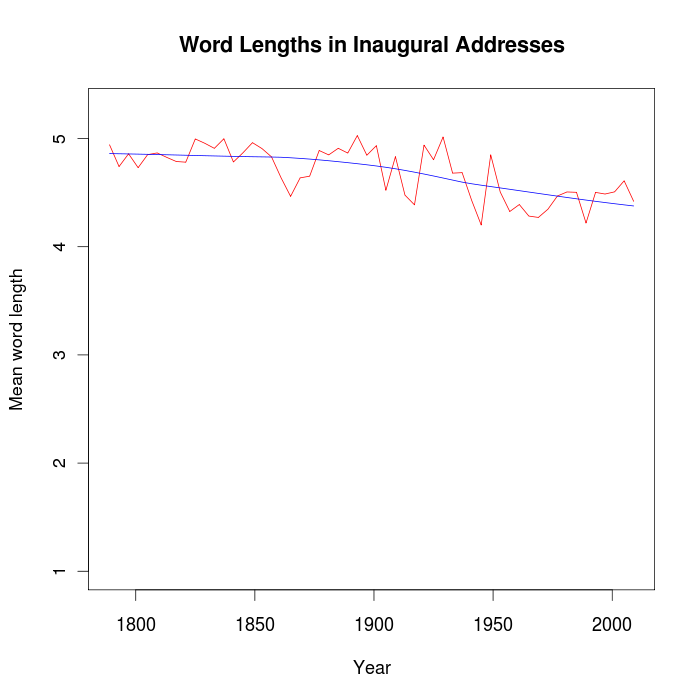

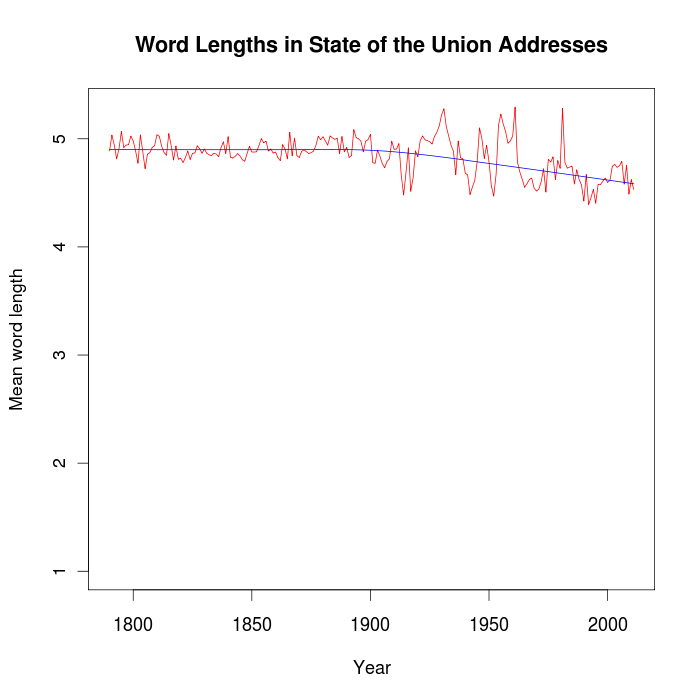

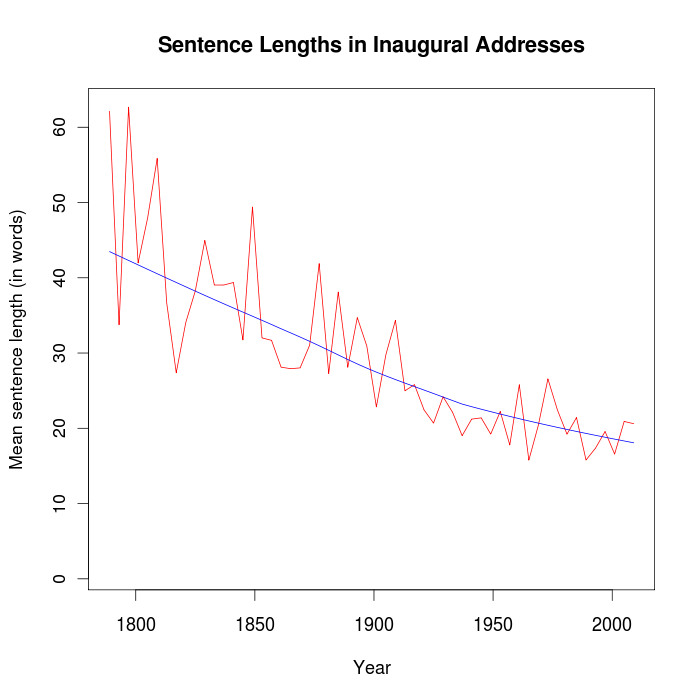

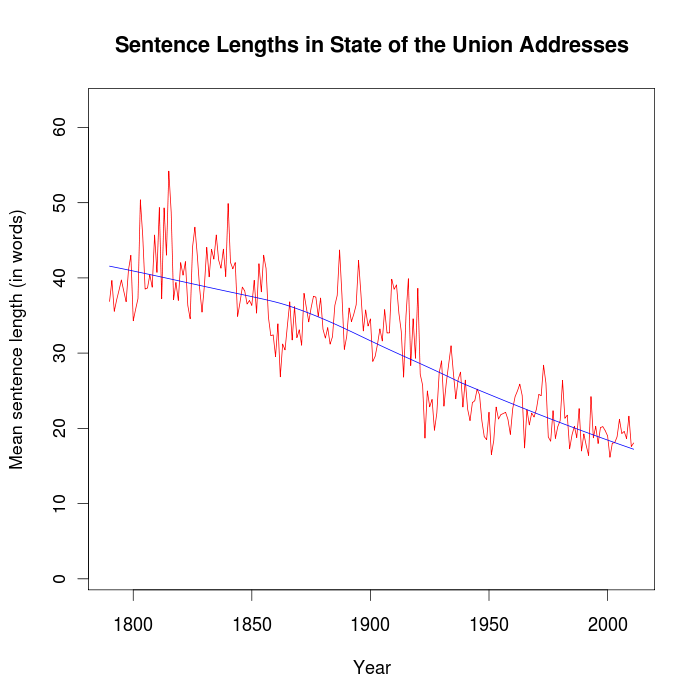

The results suggest that mean word lengths have decreased slightly in these addresses over the past century — by 5% or so — while mean sentence lengths have been falling since the founding of the republic, and have undergone a cumulative drop of perhaps 50%.

|

|

|

|

(In the plots above, the red lines track the address-by-address measurements as my scripts calculated them, while the blue lines are smoothed approximations produced by locally-weighted scatterplot smoothing in R.)

There are lots of obvious questions, if you care about things like this — for example, how much of the fall in mean sentence length is due to using less clausal embedding, and how much is due to splicing fewer sentences together paratactically, e.g. with semi-colons?

But whatever is going on, we can't blame (or praise) Twitter for it, since Twitter was founded in 2006, and thus could possibly have affected only the last datapoint in the Inaugural graphs, and the last five datapoints in the SOU graphs.

For a more anecdotal picture of the trend, here is the first paragraph (five sentences) of George Washington's 1789 Inaugural Address:

Among the vicissitudes incident to life no event could have filled me with greater anxieties than that of which the notification was transmitted by your order, and received on the 14th day of the present month. On the one hand, I was summoned by my country, whose voice I can never hear but with veneration and love, from a retreat which I had chosen with the fondest predilection, and, in my flattering hopes, with an immutable decision, as the asylum of my declining years — a retreat which was rendered every day more necessary as well as more dear to me by the addition of habit to inclination, and of frequent interruptions in my health to the gradual waste committed on it by time. On the other hand, the magnitude and difficulty of the trust to which the voice of my country called me, being sufficient to awaken in the wisest and most experienced of her citizens a distrustful scrutiny into his qualifications, could not but overwhelm with despondence one who (inheriting inferior endowments from nature and unpracticed in the duties of civil administration) ought to be peculiarly conscious of his own deficiencies. In this conflict of emotions all I dare aver is that it has been my faithful study to collect my duty from a just appreciation of every circumstance by which it might be affected. All I dare hope is that if, in executing this task, I have been too much swayed by a grateful remembrance of former instances, or by an affectionate sensibility to this transcendent proof of the confidence of my fellow-citizens, and have thence too little consulted my incapacity as well as disinclination for the weighty and untried cares before me, my error will be palliated by the motives which mislead me, and its consequences be judged by my country with some share of the partiality in which they originated.

And the first five sentences of Barack Obama's 2009 Inaugural Address:

My fellow citizens, I stand here today humbled by the task before us, grateful for the trust you have bestowed, mindful of the sacrifices borne by our ancestors. I thank President Bush for his service to our Nation, as well as the generosity and cooperation he has shown throughout this transition.

Forty-four Americans have now taken the Presidential oath. The words have been spoken during rising tides of prosperity and the still waters of peace. Yet every so often, the oath is taken amidst gathering clouds and raging storms.

In between, the first five sentences of Lincoln's 1861 Inaugural:

In compliance with a custom as old as the Government itself, I appear before you to address you briefly and to take in your presence the oath prescribed by the Constitution of the United States to be taken by the President "before he enters on the execution of this office."

I do not consider it necessary at present for me to discuss those matters of administration about which there is no special anxiety or excitement.

Apprehension seems to exist among the people of the Southern States that by the accession of a Republican Administration their property and their peace and personal security are to be endangered. There has never been any reasonable cause for such apprehension. Indeed, the most ample evidence to the contrary has all the while existed and been open to their inspection.

Cass said,

October 31, 2011 @ 8:58 am

Perhaps this is a way for the President to more easily reach "the common man" since the advent of radio. Pre-radio-media, only people with significant education got to hear or read these speeches (by virtue of being educated enough to participate in politics, or afford and read the newspaper regularly).

Additionally, in recent years, there seems to be an anti-intellectualism among politicians.

I'm wondering if there would be other samples more immune to these two factors?

NS said,

October 31, 2011 @ 9:23 am

I'm concerned about how often shorter sentence and word lengths are conflated with less- or anti- intellectual prose. The first paragraph of George Washington's inaugural shows his erudition, but it's also probably over-wordy and even (I daresay) stuffy. Obama's first paragraph (not to mention Lincoln's) has a kind of nobility, probably because its diction is clear and direct.

Craig said,

October 31, 2011 @ 9:25 am

I am fairly confident that a study of sentence length or complexity performed on the best-selling novel each year over the same period would show the same results — I feel like 18th century style was just more periodic, and the trend from then to now has been toward shorter sentences with fewer embedded clauses.

But this is based purely on my own unscientific observations, the way English from centuries ago just sort of "feels old". It could be that it's more common to read more literary novels from centuries ago (since they are the ones that have survived to become the classics you're likely to read now) and for what you read today to be more skewed toward "popular" (and presumably less complex?) fiction.

By the way, has anyone ever commented on the mistake in President Obama's opening lines? Forty-four Americans haven't taken the oath; forty-three have. Grover Cleveland was President #22 and #24. (Then again, if he'd said 43, I'm sure there'd be a line of pundits ready to jump on him: "He's so dumb, he doesn't even know what number president he is!")

Dan H said,

October 31, 2011 @ 10:21 am

So average word lengths have been decreasing ever since the election of the first President of the United States of America?

Clearly this shows that the Office of the President is directly responsible for destroying the English language.

[(myl) Unfortunately, there are several highly correlated co-variates, such as the U.S. Constitution, the U.S. Congress, and so on. In fact, given that the first Inaugural was in 1789, and the first SOU in 1790, it's possible that the fall of the French monarchy was the culprit. ]

Steve F said,

October 31, 2011 @ 10:30 am

@ Craig. The British comedy/quiz series QI spotted Obama's error. See here http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PA8qT5PzSS4

john jansen said,

October 31, 2011 @ 11:35 am

Regarding modern communications and language, I offer the following thought. Good writing comes from deliberation and thoughtfulness. The rules of language impose a structure and that structure has traditionally imposed a discipline which manifests itself through that deliberative process. However, the modern computer is the antithesis of something which promotes deliberation. Computers are about speed and that speed is inimical to a thoughtful process. Hence, we end up with clipped words, abbreviations and fragments of sentences. I think that over time the use of computers will radically alter the way we write and think. I am not certain that the result will be beneficial to efficient communication.

Mr Fnortner said,

October 31, 2011 @ 11:36 am

The advance of technology (Twitter being only one step of a long path) to put words on paper ever lightens the load while offering increasing flexibility, Considering that, I believe a the correlation between sentence length with writing technology is strong. The actual causes may be many, so it's not unreasonable to conjecture that embedded clauses and other stuffy elements arise from the inability to quickly or freely change one's mind mid sentence. With a quill in hand, and a rare and expensive piece of paper at hand, one would not, I imagine, want to strike out words, insert afterthoughts, or draw arrows to alternative sequences of sentences, nor would one be easily inclined to crumple paper and start over. So convoluted sentence structure seems a reasonable answer for writers of 200 or more years ago.

Craig said,

October 31, 2011 @ 12:39 pm

I'm not sure I agree with the conclusion that people seem to be drawing, that complexity of sentence structure aligns with complexity of thought. Is there really a difference between a long sentence with lots of subordination and several short sentences with less subordination if they express the same ideas? I see this more as a change of stylistic preference over time, not evidence of the deterioration of civilization.

[(myl) There's an argument that sequences whose structure is implicit rather than explicit are more complex, at least for the audience, rather than less complex — see e.g. here. Independent of that, exactly the same logical content can be expressed hypotactically ("X, because Y") or paratactically ("X. The reason for that is Y").]

It seems to me that when we read Washington's inauguaral address, in addition to being confronted with the periodic style, we notice that his language uses words and phrases in older senses that are less familiar to us now. Because this makes his language more difficult for us to understand instantly (whereas Obama's speech is easy), it's natural for us to draw the conclusion that Washington's writing is more intelligent, and that our difficulty in understanding it comes from an erosion in intelligence. But I think it's just a natural result of subtle and gradual changes in the language over time. I suspect that 21st century English would be just as difficult for Washington to understand as ours is for him.

[(myl) Washington's first Inaugural, frankly, is written in a rather convoluted and opaque style. Perhaps Jefferson could have expressed the same ideas more clearly, though the complexity of his sentences might have been similar.]

Craig said,

October 31, 2011 @ 12:45 pm

Thanks Steve F. And thanks to all British comedians for their valuable contributions correcting American politicians' mistakes about American history!

Brian said,

October 31, 2011 @ 1:21 pm

I wonder if the change in sentence length might also be due to the fact that, until relatively recently, the vast majority of people would be expected to read the speech instead of actually hear it. (For me at least, complex sentence structures are much easier to deal with on the page.)

Dan Hemmens said,

October 31, 2011 @ 1:49 pm

However, the modern computer is the antithesis of something which promotes deliberation. Computers are about speed and that speed is inimical to a thoughtful process. Hence, we end up with clipped words, abbreviations and fragments of sentences

Would that be the modern computer which dates back to 1800? Because if not then we've got a bit of a problem, since the data here clearly shows that sentences have been getting shorter for *two centuries*.

I'm also not convinced that the modern computer *is* the "antithesis of something which promotes deliberation". Why exactly is writing with a keyboard on a screen less conducive to deliberation than writing with a pen and ink? Because you can edit what you write? Are we to believe that editing produces bad writing, that published material would be improved if people were forced to print their first drafts without checking or proofreading?

What the computer *has* done is made written communication more *common* and therefore made it easier to use for informal communication. The reason that the average email is less carefully composed than the average formal letter is that the average email is not doing the *job* of a formal letter. Formal letters written on computers are – funnily enough – exactly as formal as formal letters written on paper.

Matt McIrvin said,

October 31, 2011 @ 2:19 pm

Benjamin Franklin would have been even pithier than Jefferson. But Franklin was born over 20 years before Washington and his style was presumably even more old-fashioned. Maybe there's a cyclic effect, or maybe I'm overgeneralizing from individuals (Franklin was also an extremely accomplished writer who specialized in the snappy epigram).

The Ridger said,

October 31, 2011 @ 3:05 pm

I think there's a great deal to be said for taking the intended audience into account. Reading something is a vastly different experience than hearing it. How much you can hold in your head doesn't change, but how easily you can go back and refresh does.

Also, if we read letters and journals from the 17th and 18th century, we see that they aren't as complex as speeches. Dan Hemmens is correct: the computer has made more people able to publish.

Ran Ari-Gur said,

October 31, 2011 @ 3:06 pm

I think I agree with George Orwell's complaint in "Politics and the English Language" (1946): the modern, Washingtonian style, with its Latinate words and long sentences, seems much inferior to the older, Obamanian style.

Also, @Craig: Bill Poser posted about it at the time: http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=1038

peterv said,

October 31, 2011 @ 3:10 pm

"Forty-four Americans have now taken the Presidential oath. "

Was George Washington an American when sworn in?

Jonathon said,

October 31, 2011 @ 3:29 pm

It seems to me that the decrease in word and sentence length corresponds at least in part with the plain style movement. There's certainly been a lot of writing advice in the last century advocating short, Germanic words over long, Latinate ones, omitting needless words, and so on.

Dan Hemmens said,

October 31, 2011 @ 4:12 pm

It occurs to me that since Grover Cleveland unambiguously does count as two Presidents, it is not unreasonable for him to count as two Americans.

Lance said,

October 31, 2011 @ 4:18 pm

I suspect that many American historians would agree that, with four years to reflect, the Grover Cleveland who took office in March of 1893 was a very different man than the Grover Cleveland who took office in March of 1885. Ergo…

Though of course it's not the case anyway that "forty-four Americans have now taken the Presidential oath", since Barack Obama isn't an oh never mind it's not even worth it.

Mr Fnortner said,

October 31, 2011 @ 4:45 pm

@peterv: Was George Washington an American when sworn in?

Srsly? GW was born in Virginia (at an early age); the Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776, the US Constitution was ratified in 1788, and Washington took office in 1789. Any or all of those would make him "an American" by the time he became president.

peterv said,

October 31, 2011 @ 5:16 pm

Mr Fnortner: Yes, seriously. Presumably, being born in Virgina before the Revolutionary War, Washington was born a British subject. If he was an American citizen at the time he took his oath of office, at what point did he cease to be a British subject and become an American citizen? Did everyone resident in what is now the USA also automatically become an American citizen at that point, or did each person have to elect to become an American citizen? My questions are asked sincerely.

Ran Ari-Gur said,

October 31, 2011 @ 6:16 pm

@peterv: Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution declares in part:

> No Person except a natural born Citizen, or a Citizen of the United States, at the time of the Adoption of this Constitution, shall be eligible to the Office of President; neither shall any Person be eligible to that Office who shall not have attained to the Age of thirty five Years, and been fourteen Years a Resident within the United States.

So it appears that Washington must have been a U.S. citizen by September 17th, 1787, at least, if not before.

Jon Weinberg said,

October 31, 2011 @ 6:29 pm

@peterv: Washington's contemporaries considered him to have been a citizen when he took his oath of office. The just-enacted Constitution required the President to be "a natural born citizen, or a citizen of the United States at the time of the adoption of this Constitution." Had Washington not been understood to be a U.S. citizen, he would not have been deemed eligible. More generally, had Washington and other persons similarly situated not been understood to have been U.S. citizens, then nobody would have been eligible to become President in 1789.

Congress never enacted any statute declaring the folks who were resident in the U.S. in 1776 to be now U.S. citizens, or requiring any renunciation or election. The contemporary understanding was that by virtue of the law of nations as it was then understood, all of those people became U.S. citizens automatically.

Jon Lennox said,

October 31, 2011 @ 6:36 pm

Is there an equivalent multi-century corpus for UK English? Perhaps Hansard or the throne speech?

Tom Recht said,

October 31, 2011 @ 8:24 pm

Craig wrote: I suspect that 21st century English would be just as difficult for Washington to understand as ours is for him.

– and neither myl in his reply nor anyone else seems to have noticed the accidental pronoun switch. One more good example, if any were needed, of how natural assumptions of construal can blithely ignore syntax.

Lindsay Costelloe said,

October 31, 2011 @ 10:19 pm

From written texts from the late 18th century, I get the impression that the formal registers of English tended toward a verbose style and somewhat latinate/greek vocabulary. It is worth remembering that anyone with any kind of education would have had knowledge of both Greek and Latin and the consequent related vocabulary in English. It's pretty rare to find that today in this time of "universal" education.

Jerry Friedman said,

October 31, 2011 @ 10:37 pm

@peterv: To amplify what others have said, the United States was officially created in March, 1781, by the Articles of Confederation. At this point Washington implicitly became an American citizen according to American law. In October, 1781, the British forces at Yorktown surrendered, and Britain no longer had any reasonable claim to be ruling the region. In 1783, Britain officially recognized the U. S. by treaties in Paris, so even technically Washington was no longer a British subject.

I had a look at the Articles of Confederation and the Treaty of Paris, and they don't say anything about citizenship. Apparently you chose with your feet. Some small percentage of American colonists left, mostly for Canada, and they remained British subjects, while everyone who stayed in the new states was an American citizen.

Craig said,

November 1, 2011 @ 1:05 am

@ Tom Recht

I had to re-read what I wrote three times before I even saw the problem! I think I am especially bad about reversing pronouns like that. I agree that it is a good example of the looseness that is permissable in syntax without hindering meaning.

@Ran Ari-Gur

Now that I look back at Bill Poser's posting from 2009 I vaguely remember having read it at the time. Perhaps what I thought was a clever observation on my part was just a re-activated memory.

@myl

I agree with you that Washington's style in that address is opaque, and perhaps would have seemed so to his contemporaries. But I still stand by my hypothesis as at least a partial explanation of why people look back at grand old examples of language, think, "My, this is difficult even for an intelligent person like me to understand. And this is how people talked back then?" and then lament the collapse of English today.

Just reading the first sentence, the modern reader is confronted with the word "vicissitudes" which is not currently in common use except in a few fixed expressions, "incident" used as an adjective in a sense that is not in common use, and a relative clause ("that of which the notification is transmitted") structured in a way that few speakers today would naturally do. Every point like this forces the modern reader to pause and think for a moment, interrupting the natural flow of understanding the language. The result is a gut feeling that Washington's English is more complicated than ours, which leads to the impression that language has deteriorated since his time. But, as I said (or meant), the fact that there are doubtless just as many words and phrases in modern English that would not have been current in the 18th century would probably make Washington's experience reading Obama's speech (if such a thing were possible) similar to our experience reading Washington's, at least in that regard. But of course this is impossible to prove.

Jeroen Mostert said,

November 1, 2011 @ 1:12 am

Given that 1776 was rather unprecedented, I think we can forgive the Americans a little procedural impropriety when it came to reassigning citizenship. That said, if Jefferson et al. could pen a lofty discourse to "place before mankind the common sense of the subject, in terms so plain and firm as to command their assent", you'd expect someone to have thrown a little more law at it.

On the other hand, there's a sort of American obviousness to it that would seem to make this unnecessary. If you have to ask what makes Americans American, you'll never know (and calling the citizenship of your president in question seems curiously /unpatriotic/ — but don't tell anyone I said that).

Martin B said,

November 1, 2011 @ 3:49 am

Using the method of ocular trauma it seems that the decline in sentence lengths isn't very smooth, but rather is reasonably constant for periods (eg 1800-1850, 1860-1920, 1940-) and then followed by a relatively rapid declines, almost like a step function. Obviously this is just one small dataset though.

[(myl) Gotta be that Kondratiev cycle, don't you think :-) ?]

John Walden said,

November 1, 2011 @ 4:58 am

Although Washington's and Lincoln's speeches were both going to be read by many and heard by very few, weren't degrees of literacy an issue? In Washington's day the literate audience was perhaps a more literary one too, whereas by 1860 more people could read but perhaps less well. US illiteracy was at 20% in 1870 and 10% in 1900 (http://nces.ed.gov/naal/lit_history.asp) so I'm guessing you can extrapolate back to a country with fewer literate people in it. However, I can see suggestions online that the US in 1800 was largely literate: Dupont de Nemours said in 1812 that fewer than 4 in 1000 Americans were innumerate and illiterate, though you wonder about his methods or if he included slaves and indentured servants. Lincoln's simpler English might then be explained by immigration from Europe making the US a very different place, with immigrant Americans increasingly literate but not to the extent of coping with English in Washington's style, leading to a generally simpler English bearing their needs in mind.

Jon Weinberg said,

November 1, 2011 @ 6:29 am

@Jeroen Mostert: During the Revolutionary period, the states were the primary legal authorities, and at least some of them seem to have addressed the issue, if in a peremptory way. New Jersey, for example, enacted a law on October 4, 1776 called an "Act to punish Traitors and disaffected Persons." It declared the local citizenship of all persons abiding there and stated that anyone who aided or abetted the British army or defended the authority of Great Britain was guilty of treason.

This sweeping declaration left a little tidying up to do. A case reached the U.S. Supreme Court in which the claim was that one Daniel Coxe, who "took no part in favour of the revolution but joined the British army in an early stage of the war, and from that time to this, by the whole tenor of his actions and declarations, has shewn his election not to be a citizen of the U.S. but to adhere to the British empire," was not a U.S. citizen in 1802, and was ineligible to inherit land in New Jersey. The Justices ruled in favor of Coxe's claim.

Ben Hemmens said,

November 1, 2011 @ 7:14 am

It's easier to make sentences shorter when you have a word processor. Recently I started drafting some texts on paper again, and I find I can quite easily use up a whole page working on one sentence.

Maybe poor George Washington was just short of paper; or maybe (more seriously) the length of sentences is affected by the relative ease of adding more words compared to deleting and starting over.

Jon Weinberg said,

November 1, 2011 @ 7:14 am

(Just in case I wasn't clear: The Justices ruled that Coxe did legally inherit the land, his Loyalism notwithstanding. They rejected the argument that he was ineligible to do so.)

Dan H said,

November 1, 2011 @ 7:20 am

It's easier to make sentences shorter when you have a word processor.

True, but it's also easier to make them longer, and the trend described in the post significantly predates the invention of word processing software.

Ben Hemmens said,

November 1, 2011 @ 7:24 am

@john jansen:

However, the modern computer is the antithesis of something which promotes deliberation.

I don't believe that at all. A computer, especially when using a text editor/ word processor with the kind of undo/redo functions we have now, allows one to work over text back and forth much more than on paper.

I sometimes get irritated by clients who want to "see the changes" in their text, by which they mean the want me to use Word's change-tracking function, which I loathe. I often feel like shouting "The changes are **** everywhere; I've rewritten every one of your ***** sentences at least 4 times!" But nowadays I meekly generate a file using "Compare documents", if it makes them feel better.

Ben Hemmens said,

November 1, 2011 @ 7:27 am

@ Dan:

the trend described in the post significantly predates the invention of word processing software.

Indeed, but most POTUSes have had something quite similar in the form of an unlimited supply of paper and secretaries who take dictation ;-)

Dan H said,

November 1, 2011 @ 7:29 am

True, but then you'd expect sentences to have a uniformly low word count. I'm pretty sure this is a trend in fashion rather than the influence of technology.

When will people realise that technology doesn’t wreck language? « thesociallinguist said,

November 1, 2011 @ 7:30 am

[…] not even going to try and compete with the brilliant analysis/discussion over the the Language Log, here, here and here), but Fiennes' comments bely a deeper distrust among certain sections of […]

RP said,

November 1, 2011 @ 8:19 am

It seems that in discussing whether Washington was an American, people are interpreting "American" as meaning US citizen. But could "American" not equally well mean "resident of the Americas" or alternatively "person born in the Americas" or "person born in British America"? Indeed, the word "Irishman" continued in use throughout the period that Ireland was a colony and there were "Indians" beofre Indian independence, and I'd be surprised if the same wasn't true of Australia. There is such a thing as a Catalan, a Basque, or a Scot, or a Yorkshireman, or a Londoner (I don't mean to imply that these examples are all directly comparable to one another).

Anyway, I think Dan Hemmens is right: if Grover counts as two presidents, there is no good reason not to count him as two Americans as well. On the face of it, there are excellent reasons for not counting him as two presidents, but it seems that tradition and custom argue strongly that we should.

Mr Fnortner said,

November 1, 2011 @ 9:08 am

Cleveland's heft clearly made him 1½ Americans, and I suppose the remaining half came from being so successful at the polls (he won three times).

J. W. Brewer said,

November 1, 2011 @ 9:51 am

The Treaty of Paris assumes the existence as of 1783 of citizens of the United States, in the sentence reading: "There shall be a firm and perpetual peace between his Brittanic Majesty and the said states, and between the subjects of the one and the citizens of the other, wherefore all hostilities both by sea and land shall from henceforth cease." Arguably one could say that Washington was a citizen of the Commonwealth of Virginia and thus derivitatively of the U.S. Naturalization was handled at the state level during the period of the Articles of Confederation, which Federalist 42 claims was unsatisfactory, leading to the subsequent Constitutional authorization of Congress to make uniform rules in that area.

Jerry Friedman said,

November 1, 2011 @ 12:39 pm

@RP: You're right—the OED's first citation for unhyphenated "American" in the sense of a person of non-indigenous descent in the Americas is from 1691 ("C. Mather Triumphs Reformed Relig. in Amer. 88 A rude American."). I didn't address that sense because peterv had made it clear in his second comment that he was talking about citizenship. But of course Washington was an American either way, so it doesn't matter to Obama's miscount.

Mark F. said,

November 1, 2011 @ 4:28 pm

I think Craig makes a good point that the unfamiliarity of the language of the past can make it more challenging and hence make it seem more sophisticated. But the style of Washington's speech wasn't just more alien to us than that of Obama's, it was in particular more formal. If you're someone who likes formality, then by your lights (I think) there will have been a genuine decline in our tastes.

I really don't think it's just a matter of a change in how much embedding is expected in the most formal speech, although that certainly has changed. I think people expect formal speeches to be more like speech among friends than they used to, and that's part of the reason for the nature of the stylistic change. (Part of why I think this is that I read it in a book by John McWhorter, but I thought he made a pretty good case.)

Philip said,

November 1, 2011 @ 4:50 pm

Sentence length has decreased by 50 percent over the past 200 years.

More embeddings or more splicing sentences together paratatically, with, for example, semicolons? I'd guess some of both, but with more of the latter than the former.

But, for sure, short sentences were in vogue in literature–probably because of the influence of Ernest Hemingway. When Norman Mailer was campaigining for H's heavyweight championship of American letters, he was credited for having "revivified the long sentence."

[(myl) In fact, Hemingway's sentences are not always all that short, though they tend to be relatively flat. Thus the sentence lengths in the first paragraph of The Old Man and the Sea are 26,11,49,45,17 words, for an average of 29.6.]

Dan Hemmens said,

November 1, 2011 @ 5:35 pm

I really don't think it's just a matter of a change in how much embedding is expected in the most formal speech, although that certainly has changed. I think people expect formal speeches to be more like speech among friends than they used to, and that's part of the reason for the nature of the stylistic change.

On a purely technical level, I'm having a bit of trouble getting my head around the idea of formal speeches becoming less formal. Surely by definition a formal speech is formal? I suppose you could argue that *political* speeches have become less formal while other sorts of speeches have retained the old formal structures, but I'm not sure that doesn't lead to circular reasoning (in that there's a danger of assuming that because a speech uses less embedding that it is therefore inherently less formal, meaning that the amount of embedding used in formal speeches by definition stays constant).

That said, it does seem reasonable that the change in sentence-structures in presidential speeches may be less to do with overall changes in language and more to do with changes in the perceived relationship between the president and the people (I'd be interested in seeing a similar analysis of Queen's speeches).

Eric P Smith said,

November 1, 2011 @ 6:56 pm

@Dan Hemmens: I am happy with “Formal speeches are becoming more formal,” just as I might say “The rich are becoming richer, and the poor are becoming poorer.”

Janice Byer said,

November 1, 2011 @ 8:11 pm

The ellipsis in formal speeches becoming less formal [in their literary style] is obvious, imo, and, given the topic, a nice touch.

jamessal said,

November 1, 2011 @ 9:46 pm

In fact, Hemingway's sentences are not always all that short

But they are still paratactic, at least according to the way some prose theorists use the term (e.g., Richard Lanham); hence the popular misconception. Like Cormac McCarthy's famously criticized sentence from The Crossing — "He ate the last of the eggs and wiped the plate with the tortilla and ate the tortilla and drank the last of the coffee and wiped his mouth and looked up and thanked her" — a decent amount of Hemingway's prose is (again using Lanham's terminology) paratactic but polysyndetic.

maidhc said,

November 2, 2011 @ 2:13 am

There were 8 US presidents before Washington. Under the Articles of Confederation, the presidential term was one year. I imagine they took some kind of oath, but obviously not the current one that requires upholding the Constitution.

Alexander Hamilton was considered an American citizen even though he was born in the West Indies. But Native Americans were not considered citizens, I believe. And I don't believe there was a consensus about the citizenship of free blacks, even though some of them fought in the Revolution.

Faldone said,

November 2, 2011 @ 6:22 am

The presidents before Washington were not President of the United States. They weren't even president of the United States in Congress. They were the president of the Committee of States, a committee that sat in session when the congress was in recess.

Janice Byer said,

November 2, 2011 @ 11:26 am

Born in the British West Indies to an unwed mother, Alexander Hamilton was granted US citizenship by virtue of his having served honorably throughout the War of Independence from its inception in Boston (where he'd been sent in 1772 to attend school, because Church of England rules then forbade higher education to illegitimate children) firstly as a volunteer in an artillery unit, rising in ranks to become its captain and lastly as General George Washington's aide de camp. Although he served in Washington's cabinet as our first Secretary of Treasury, Hamilton was ineligible to become US president.

Native Americans who didn't pledge their loyalty to the British Crown during the War or take up arms against the Americans alongside the Redcoats, did indeed have a right to assume American citizenship and were naturally eligible for the presidency.

maidhc said,

November 3, 2011 @ 2:36 am

If the Cherokee Indians were American citizens, Andrew Jackson would have had no right to steal their land and send them on the Trail of Tears. Which is what the Supreme Court said, but that didn't stop him.

Ben Hemmens said,

November 3, 2011 @ 4:40 am

Thanks to jamessal for mentioning Richard Lanham. He seems interesting.

jamessal said,

November 4, 2011 @ 3:12 am

Oh, you're most welcome! And Lanham is interesting: his (kinda lamely titled) Style: An Anti-Textbook is a breezy, funny, beautifully written introduction to his thinking (he always writes beautifully); Analyzing Prose explicates his theories further, and is definitely worth the time (and probably the money — if I remember right, it's about forty bucks), although it's not as funny.

B Grover said,

November 4, 2011 @ 4:57 am

My own speculation runs to the thought that the internationalization of English has led to its foreshortening, though I must admit that many foreign speakers of my acquaintance use better grammar and have broader vocabularies than the average native. Written discourse with college graduates in recent years is cause for despair. Their inability to formulate a coherent argument, much less spell and punctuation correctly, is a sad commentary on the education system, much less any form of electronic communication.

If we are to blame any form of communication for the demise of the English language, I would look first to the telegraph, which effects are still seen in PowerPoint presentations across the globe. Since 'telegraph English' is an actual topic of study in ESL courses, perhaps it won't be long before we see 'Twitter Tongue' taught along side. it.

The hallmark of a living language is that it continues to evolve over time. Certainly, no one speaks like Shakespeare, even in the Queen's Chamber. What will truly be disaster is that English should lose its broad ability to express such subtle shades of emotion and detail, as it can at present.

Rod Johnson said,

November 4, 2011 @ 10:49 am

Cite please. I teach writing to college students—engineering students, no less—and can't discern a real difference between them and students of my era. I see mistakes and infelicities, yes—not unlike saying "spell and punctuation correctly"—but have those not always been there? What I don't see is evidence of an overall decline. Part of the problem is that the evidence people bring forward is always selective. Yes, if you compare the writing of the elite students of a more selective era with the whole range of students now, you're going to see some differences—but have you actually compared apples to apples? Or looked critically at the standards by which you're judging those apples?

And—"telegraph English" in ESL? Can you expand on that? I've never encountered it, and Google is no help.

Dan Hemmens said,

November 4, 2011 @ 1:37 pm

What will truly be disaster is that English should lose its broad ability to express such subtle shades of emotion and detail, as it can at present.

It would take somebody with a far better linguistics background than me to make a statement on this, but I am pretty sure that one of the defining features of human languages is their ability to express an unlimited number of concepts, and to be adapted dynamically to express new and unfamiliar concepts.

This being the case, I am pretty certain it is *completely impossible* for English to lose its ability to "express such subtle shades of emotion and detail".

I'd also point out that if you want examples of the way the English language expresses subtle shades of emotion and detail, you would be hard pressed to find a better example than the subtle yet beautiful distinctions between such things as the lol and the rofl, or the facepalm and the headdesk.

The notion that the English language is becoming less expressive is so cracktastic that I'd find it lolworthy if I wasn't so busy headdesking.

B Grover said,

November 5, 2011 @ 6:30 pm

Rod and Dan:

You made my point most eloquently. 'LOL' is a prime example of the abbreviating of the language. Not only does it fail to fully write out the concept, but it completely ignores such subtleties as smirk, grin, chortle, chuckle, and guffaw, among others. I also seriously doubt that someone who writes 'rofl' is actually rolling on the floor laughing. It is, however, a fine example of 'telegraph English,' in that it drops the subject and an article, as well as leaves off a perfectly good verb, such that, "I am rolling on the floor laughing," becomes "rolling on floor laughing," which is then compressed to 'rofl.'

I thank you for making my point so well.

As for citations, as I am writing extemporaneously without extensive research, I can not provide citations with any certainty. However, since I am a polyglot fluent in four languages, conversant in another ten, and passingly familiar with a half-dozen or so beyond that, I am a professional, award-winning writer and currently employed as an editor, and I am an English teacher whose mother was an English teacher, I do speak with some experience and authority of my own.

English has the largest vocabulary of any language on Earth, and is the only one I am familiar with that produces a thesaurus, allowing one to choose the precise word for any occasion. Certainly, if people do not use such a wealth of verbal resources, they will be lost at some point and the language will further contract, losing its ability to express many subtleties. That it is impossible is absurd, since the number of obsolete words in English is quite large. That languages die is further proof that they can lose significant parts of themselves. After all, how many folks do you know that regularly chat in Phoenician, Babylonian, Sanskrit, or Latin? If entire systems of communication can die out, then it stands to reason that parts of languages can die, as well.

And yes, I was aware of the mistakes in my previous posting. I thought it rather amusing to use a pompous style, complaining about incorrect usage of English, on a message board devoted to language, while having several glaring mistakes in my post. Perhaps my attempt at humor was far too subtle for the 'lol' crowd. It's enough to make me headdesk, but at least I'm not gob-smacked.

Dan Hemmens said,

November 5, 2011 @ 7:26 pm

Not only does it fail to fully write out the concept, but it completely ignores such subtleties as smirk, grin, chortle, chuckle, and guffaw, among others.

"lol" no more ignores smirk, grin, chortle, chuckle and guffaw than guffaw ignores smirk, grin, chortle, chuckle and lol. Using one word does not imply ignorance of other words. There are specific contexts in which "lol" is the *correct* word to use and any of the other words you cite are *incorrect* either because they simply do not have the same meaning, or because they have the wrong register.

However, since I am a polyglot fluent in four languages, conversant in another ten, and passingly familiar with a half-dozen or so beyond that, I am a professional, award-winning writer and currently employed as an editor, and I am an English teacher whose mother was an English teacher, I do speak with some experience and authority of my own.

Experience and authority are of little use when one is simply *wrong*.

You assert that English is in danger of losing its ability to express subtlety of emotion and detail. This is – as I understand it – literally impossible.

English has the largest vocabulary of any language on Earth, and is the only one I am familiar with that produces a thesaurus, allowing one to choose the precise word for any occasion.

Firstly, vocabulary size is not a measure of the expressiveness of a language.

Secondly, "English" does not produce a thesaurus, people produce thesauruses in English. I have no idea whether they produce them in other languages as well, but I see no reason that one could not.

Thirdly, a thesaurus does not allow one to "choose the precise word for any occasion". It allows one to look up synonyms for words. I might also point out that the thesaurus is frequently the absolute *bane* of clear expression, since it so often consists of nothing but a blind list of words with no hints about how their senses differ.

A brief thesaurus search for the word "laugh" gives: " break up, burst*, cachinnate, chortle, chuckle, convulsed, crack up, crow, die laughing, fracture, giggle, grin, guffaw, howl, roar, roll in the aisles, scream, shriek, snicker, snort, split one's sides, titter, whoop, with sound be in stitches" with no indication of how these words or phrases should be used, or what other implications they might have. It is no help whatsoever in choosing the right word to describe a particular kind of laughter (which, nine times out of ten, will simply be "laugh").

That languages die is further proof that they can lose significant parts of themselves. After all, how many folks do you know that regularly chat in Phoenician, Babylonian, Sanskrit, or Latin? If entire systems of communication can die out, then it stands to reason that parts of languages can die, as well.

That's faulty logic and poor rhetoric. Languages die when people stop speaking them. Parts of languages die when people stop using those parts of the language, but there is a massive difference between languages losing *elements* and losing *functionality*.

English may well be losing a number of subtle distinctions – say the distinction between "less" and "fewer" but that does not mean that the language will become incapable of distinguishing between "a smaller number" and "a smaller quantity" (insofar as that distinction is ever anything but obvious) it merely means that the distinction will no longer be coded into a single word.

I thought it rather amusing to use a pompous style, complaining about incorrect usage of English, on a message board devoted to language, while having several glaring mistakes in my post.

You found it amusing to make yourself look like a fool?

You are *still* posting in a pompous style, you are still complaining, and you are still making glaring mistakes. I am glad that you find it amusing, but I suspect that you are in a minority of one. I have personally read far too much uninformed, inarticulate nonsense about the decline of the English language to be remotely amused by your rather pedestrian examples.

Rod Johnson said,

November 5, 2011 @ 9:39 pm

What a compendium of peever cliches. Troll or poe? If B Grover did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him.

Dan Hemmens said,

November 6, 2011 @ 6:49 am

What a compendium of peever cliches. Troll or poe? If B Grover did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him.

Surely that should be "were it the case that he did not exist, it should have been necessary to invent him". Does nobody learn the subjective tense these days?

Incidentally two minutes with google reveals at least one onine French thesaurus (http://www.dictionnaire-synonymes.com/), reviews of several Japanese thesauruses (http://www.kanjiclinic.com/reviewthesaurus.htm) and similar tools in other languages.

Janice Byer said,

November 7, 2011 @ 3:52 pm

Steve Jobs's online detractors have had bigger sins to fry him for, since his death, than what they've presumed is his mindless shortening of a word, but to pettifoggers, size doesn't matter. The prescriptivists among them have had their way with, "Think Different". His newly-released biography gratifyingly reveals his deliberation and intent:

From Walter Isaacson's "Steve Jobs":

They debated the grammatical issue: If “different” was supposed to modify the verb “think,” it should be an adverb, as in “think differently.” But Jobs insisted that he wanted “different” to be used as a noun, as in “think victory” or “think beauty.” Also, it echoed colloquial use, as in “think big.” Jobs later explained, "We discussed whether it was correct before we ran it. It’s grammatical, if you think about what we’re trying to say. It’s not think the same, it’s think different. Think a little different, think a lot different, think different. "Think differently’" wouldn’t hit the meaning for me."

Dan Hemmens said,

November 7, 2011 @ 4:39 pm

Also, it echoed colloquial use, as in “think big.”

I'm very tempted to make my personal motto "think bigly".

jamessal said,

November 8, 2011 @ 10:23 pm

B. Grover: What will truly be disaster is that English should lose its broad ability to express such subtle shades of emotion and detail, as it can at present.

Dan Hemmens: It would take somebody with a far better linguistics background than me to make a statement on this

Good call; I'd stay out of it. Even the keen lay observer has trouble distinguishing post festum between horse- and bullshit. Better let those with the degrees bag and tag this steamer.

since I am a polyglot fluent in four languages, conversant in another ten, and passingly familiar with a half-dozen or so beyond that, I am a professional, award-winning writer and currently employed as an editor, and I am an English teacher whose mother was an English teacher, I do speak with some experience and authority of my own.

And since I eat every day of my life — more than once — and often order from restaurants colloquially called "ethnic," then I needn't defer to Harold McGee on the subject of food or science, or to any other food scientist for that matter, especially — and I mean especially — not to a group of them kind enough to contribute to a blog popularizing their subject of expertise. I eat, dammit — I know food!

I was aware of the mistakes in my previous posting. I thought it rather amusing to use a pompous style, complaining about incorrect usage of English, on a message board devoted to language, while having several glaring mistakes in my post. Perhaps my attempt at humor was far too subtle for the 'lol' crowd.

Irony that doesn't quite come across is a… what was the word you used so sloppily (albeit with intentional sloppiness, of course)? Ah, yes, "hallmark"! It's a hallmark of shitty writing.

jamessal said,

November 8, 2011 @ 10:41 pm

And I'm guessing "polyglot fluent in four languages" was an ironic, intentional redundancy, because there's no way a "professional, award-winning writer" would be so insecure as to need to prove to a bunch of strangers online that he knew the meaning of an SAT quiz word like "polyglot," is there? No, you must have just made a simple, forgivable mistake — no need to patch together theories about your personality from such scant evidence. I, after all, don't know any more about you than you do about the subject you're so eager to pontificate about: linguistics.

Max said,

January 24, 2012 @ 5:17 pm

From 1801-1913, the State of the Union was delivered as a letter, rather than a speech, so it was written for the page. The surge in sentence lengths strongly correlates with that period.

Dan Creamer said,

February 2, 2012 @ 3:00 am

There is little doubt that the quality of erudition inherent in today’s politicians is lacking in comparison to men the likes of Washington, and his contemporaries. There is also a predilection in academia, to teach students to value parsimony in the use of vocabulary when constructing written missives. Additionally, the use of vocabulary of the more esoteric quality is frowned upon, because of the danger of confusing the reader with words they likely are unfamiliar with, due to in my opinion a sorrowful diminishment in the quality of education they have available to them, or are generally willing to pursue.

Thomas said,

April 9, 2012 @ 3:20 pm

Concerning Sentence Length:

Though it seems that sentence length has shortened, it is not necessarily a bad thing in all cases. Poetry is one of the most beautiful and certainly the oldest of the type of writing, and it uses precise language, which makes the sentences shorter. Also, the cause for the shortening of sentences may not be completely caused by the writer; it may be unconsciously be derived from a less sophisticated audience. Certainly, the cause is a mixture of the two but probably involves a bit of influence from the audience.

Is Twitter Destroying the English language? | Read, Write, Now said,

April 28, 2012 @ 11:24 am

[…] is negatively affected by modern communication tools likeTwitter, Mark Liberman undertook a brief analysis comparing the inaugural addresses of various Presidents. This analysis can be found on University […]

Dave said,

May 8, 2012 @ 7:30 pm

One difference might be the target audience for the speeches. Today, presidents address themselves to an elite few, and not to the general population. The elite audience understands coded and abbreviated language, and looks only for affirmation of intent; that the president is committed to the execution of special interest policies, and that he understands the desires of his financial masters and is willing to execute the agreed-upon plan. It is all about saying "I am with you" to the chosen few. It doesn't take many words to convey a coded message. That, and the average American who watches TV is dumb as a freaking post, and the president can't come off as too educated or erudite lest he be deemed "fancy" (gay) or snobbish (European).

Rich Z said,

December 3, 2012 @ 10:13 pm

I would really like to see these graphs captioned with the names of the presidents represented by each point.

CrisisMaven said,

June 20, 2014 @ 8:10 am

I think the reason for "declining" sentence length has a lot, if not everything, to do with the sociological changes in secondary and tertiary education. Back when Lincoln or Washington were presidents, a tiny, tiny group of citizens would have a high school equivalent secondary education. There was no matriculation examination since "everyone" who could afford to and be considered mature enough to attend a lecture was automatically qualified. While today more than 50% of the population of all Western and most Asian countries qualify for university access, at the time of Washington it was maybe less than half a percent. So when Washington would sit in class (or being home-schooled) he would be addressed by venerated teachers who themselves today might be tenured college lecturers. The broader access to these educational institutions became, the "easier" the language would have to be to "leave no child behind". As for today's speeches, another aside: I don't think Washington or Lincoln employed ghostwriters. the Bushes, Clintons and Obamas of our modern times do …