Prehistoric notation systems in Peru, with Chinese parallels

« previous post | next post »

This morning, by chance, I learned about the great urban center of Caral in Peru, 120 miles north of Lima. It was occupied between ca. 26th century BC and 20th century BC and had more than 3,000 inhabitants. It was said to be the oldest urban center in the Americas and the largest for the 3rd millennium BC. Caral had many impressive architectural structures, including temples, an amphitheater, and pyramids that predate the Egyptian pyramids by approximately a century.

What attracted my attention the most, however, is this:

Among the artifacts found at Caral is a knotted textile piece that the excavators have labelled a quipu. They write that the artifact is evidence that the quipu record keeping system, a method involving knots tied in textiles that was brought to its highest development by the Inca Empire, was older than any archaeologist previously had determined. Evidence has emerged that the quipu also may have recorded logographic information in the same way writing does. Gary Urton has suggested that the quipus used a binary system that could record phonological or logographic data.

(source)

Ancient Chinese texts allude to similar notation systems employing knots tied in strings.

Chinese Knots.

In Asia, China specifically, one finds references to knots as means of record keeping in old texts like the Ta Chuan, Book of Change, (the Great Commentary on the I Ching, 500-220 BCE) where it is said (Section II-13): ”In the highest antiquity, government was carried on successfully by the use of knotted cords to preserve the memory of things. In subsequent ages, for these the sages substituted written characters and bonds. By means of these the doings of all the officers could be regulated, and the affairs of all people accurately examined. The idea of this was taken, probably, from the hexagram Kuai”.* Another example is in the Dao de Jing of Laozi from the time of the Warring States…. There are no known existing examples of these Chinese knotted records.

*This is based on the translation of James Legge (1815-1897). Since the website takes some liberties with the original, I quote it here directly from Legge's The Sacred Books of the East: The sacred books of China, pt. 2 (1882) and The Sacred Books of China: The Texts of Confucianism (1882), Appendix III, ch. 2, p. 385:

In the highest antiquity, government was carried on successfully by the use of knotted cords (to preserve the memory of things). In subsequent ages, the sages substituted for these written characters and bonds. By means of these (the doings of) all the officers could be regulated, and (the affairs of) all the people accurately examined. The idea of this was taken, probably, from the hexagram Kwâi (the forty-third hexagram).

上古結繩而治,後世聖人易之以書契,百官以治,萬民以察,蓋取諸夬。

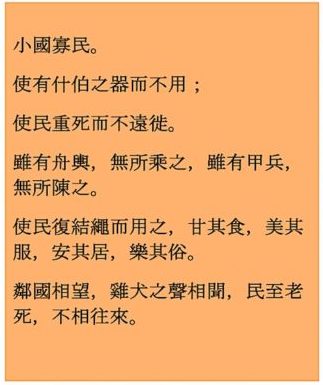

Dao De Jing / 80. (Standing alone), 老子, Laozi/道德經

[Warring States (475 BC – 221 BC)]

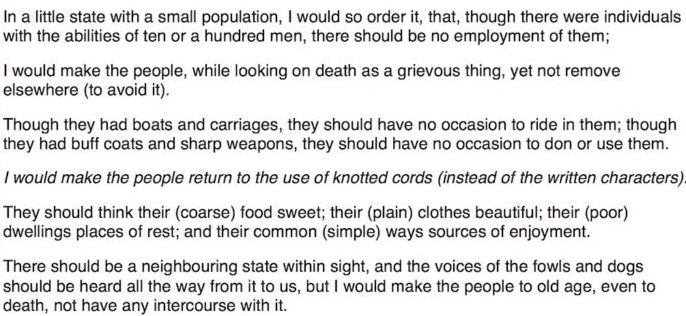

There are several English translations of this text, which vary somewhat. Here we give the publicly open translation by James Legge.

(source)

The Dao de jing / Tao Te ching uses exactly the same expression, jiéshéng 結繩 ("knotting cords"), for this notation device.

Since the word "quipu" or "khipu" with which we are comparing the Chinese jiéshéng 結繩 ("knotting cords"), though fairly well known in many languages, is yet seemingly exotic, here is some basic dictionary information about it:

Quipu is the Spanish spelling and the most common spelling in English. Khipu (pronounced [ˈkʰɪpʊ], plural: khipukuna) is the word for "knot" in Cusco Quechua. In most Quechua varieties, the term is kipu.

"Quipu" is a Quechua word meaning "knot" or "to knot". The terms "quipu" and "khipu" are simply spelling variations on the same word. "Quipu" is the traditional Spanish spelling, while "khipu" reflects the recent Quechuan and Aymaran spelling shift.

(source)

A recording device, used by the Incas, consisting of intricate knotted cords.

(source)

I was also greatly intrigued by this phenomenal discovery at Cara:

Another significant find at the site was a collection of musical instruments, including 37 cornetts made of deer and llama bones and 33 flutes of unusual construction. The flutes were radiocarbon dated to 2170±90 BC.

(source)

See the second paragraph here: "Music in the Ancient Andes".

Cf.:

[Mair 2006] Victor H. Mair. “Prehistoric European and East Asian Flutes”, contained in [Anderl 2006], 2006, pages 209–216. See the Instphi.Org web site ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

One citation: The Development of Flutes in Europe and Asia

Lead paragraph: The world's first flutes – which are also the world's first known musical instruments fashioned and played by man – were created in Europe, and were associated with a quantum leap in the overall cognitive, aesthetic, and symbolic abilities of modern human beings during the Upper Paleolithic. The cave art and plastic art from this period and region are rightly celebrated as constituting a remarkable advance in human civilization, and it is possible that modern linguistic capability arose at around the same time, perhaps for similar reasons (the expansion and increased neural complexity of the human brain), although the hominid predecessors of Homo sapiens sapiens admittedly also possessed slowly increasing capacity to represent, express, and communicate.

Flutes dated to the 6th millennium BC have also been found in China.

(source: Flutopedia: The Development of Flutes in Europe and Asia)

I consider the carefully spaced, measured, and drilled holes in these prehistoric flutes to be a type of musical notation system.

Selected readings

- "Translating the I ching (Book of Changes)" (10/11/17)

- "WU2WEI2: Do Nothing" (3/2/09)

- "Tao and Taoism" (7/13/17)

- "False Quotations and Fake Translations" (4/30/10)

- "The dissemination of iron and the spread of languages" (11/5/20)

- "Data vs. information" (2/7/21)

- "Of knots, pimples, and Sinitic reconstructions" (11/12/18)

Antonio L. Banderas said,

April 18, 2021 @ 5:09 am

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Binary_system_(disambiguation)

AntC said,

April 18, 2021 @ 6:40 am

Fascinating re the flutes! Thank you Victor.

Pictures of the Caral flutes, and some analysis of the tones they produced here

I consider the carefully spaced, measured, and drilled holes in these prehistoric flutes to be a type of musical notation system.

Heh heh, must be my Western music-attuned ears, but that sample Melody on the Replica of the Hohle Fels Griffon Vulture flute sounds like a snatch of a Rachmaninov Piano Concerto.

I think you mean not a "notation system" (which would be some sort of aide-memoire for tunes/rhythms/harmonies), but a tuning system, modes or scales. I can't detect any system in the tone measurements from the Caral flutes. (Covering both ends vs leaving them open spans an 'octave' in Western terms, but that's what you'd expect from the physics. Could do with sounding out more than three of them.) I guess it's difficult to get your Pelicans to produce identical shaped bones, no matter how well you feed them.

The European flutes you've written about, and the Chinese ones, show definite intent to produce a tuning system. The small extra hole in the Jiahu flute is to adjust to a tuning system. (It must be darn difficult to position the holes accurately when you can't control the internal shape and diameter of the bone. Cranes are no more reliable than Pelicans, it seems.)

DMBG said,

April 18, 2021 @ 7:15 am

AntC: "It must be darn difficult to position the holes accurately when you can't control the internal shape and diameter of the bone. "

I used to make bamboo flutes. I imagine bone is trickier, but there is quite a lot of leeway for hole positioning, because the pitch of the hole depends not only on its location but also on its size. You first drill a deliberately undersized pilot hole at a rough-guess location and gradually enlarge the hole until the pitch comes out right.

AntC said,

April 18, 2021 @ 6:47 pm

I used to make bamboo flutes. I imagine bone is trickier,

It's all about laminar flow (no rough intrusions inside the tube) and end corrections (esp sharp edges to your holes).

Given the Caral flutes have their embouchure in the middle, I'm guessing the clay insert/partition is to try to get smooth/laminar flow into both ends. (Contrast a modern concert flute (Boehm) has the embouchure at one end, which is closed; and a tapered/flared internal shape to the open end. Much easier to get smooth flow and control of dynamics/airflow.)

thanks @DMBG, I note bamboo is straight (or at least you use only straight cuts), and you'd have a metal straight drill-bit/rasp to smooth the inside.

Those Crane-bone flutes are quite long and noticeably curved. Even with metal instruments, it'd be a heck of a job to smoothen their insides.

Victor Mair said,

April 19, 2021 @ 9:46 am

From Wolfgang Behr:

This [knotting cords for record keeping] is an interesting topic, which could (and should) be studied in a larger comparative project. I gave a talk on related aspects in Chicago in 2014, but the conference volume never materialized. The handout is available here:

"The detrimental effects of writing: some comparative perspectives"

https://www.academia.edu/8987035/The_detrimental_effects_of_writing_some_comparative_perspectives

Victor Mair said,

April 19, 2021 @ 9:48 am

@Wolfgang Behr:

Thanks very much for telling me about your 2014 Chicago talk. I hope that you will indeed find time to write it up for publication next year while you're on leave. Please consider submitting the paper to SPP.

Ken Takashima will be publishing an important paper on OBIs in SPP within a month or two and intends to submit more papers later on.

I like your reconstruction of 包犧 as *Pru-ŋ(r)aj (can't get all the diacriticals in this e-mail — Baxter-Sagart?). It's very suggestive. I also like how you give translations (as well as reconstructions) of clan names.

I agree with you about the advisability of studying 結繩 in a comparative context. When I was preparing my Peru post, I came across references to string knotting for record keeping in many far-flung cultures. Scholars in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were already familiar with this phenomenon.

Although your draft is full and rich, below I mention just a few other items that may be of interest to you.

I did not realize before reading your draft that there was such a strong tradition of anti-writing among the Greeks, and definitely not among the Chinese.

The whole ancient Indian culture was opposed to writing and consciously rejected it for millennia after the oral composition of the Vedas, Upanishads, epics, etc. They placed heavy emphasis on mnemonics, and I have often mentioned that this incredible wealth of experience in memorization is probably somehow related to the overwhelming dominance of Indians in the spelling bees (have written many LL posts about that over the years).

The Arabs preferred the camel over trucks. See Richard Bulliet, The Camel and the Wheel.

The Japanese rejected firearms from 1543 to 1879 (incredible!). See Giving up the Gun by Noel Perrin, my old professor of English at Dartmouth.

Finally, for a most engaging and deeply perceptive account of the history of writing in China, see Lu Xun's remarkable Mén wàiwén tán 门外文谈, which I have translated in its entirety as "An Outsider's Chats about Written Language" in Hawaii Reader in Traditional Chinese Culture, pp. 617-641. Lu Xun comes as close as anyone to understanding the true relationship between writing and language in China.

I spent a lot of time on translating that whole book; I wish that more people knew about it.

Chris Button said,

April 20, 2021 @ 8:19 am

I have a copy of Gary Urton's "Signs of the Inka Khipu". I remember thinking the argument that the khipu encoded more than numbers was strong, but the suggestion (which to be fair he doesn't overly stress) that it could be a "writing" system seemed far-fetched to me. That seems to reflect more what Urton ideally would want to be the case rather than what actually is the case.

Having said that, now that Chinese has been brought up, I was always skeptical of Pulleyblank's suggestion that the tiangan dizhi might have represented an "alphabet" of sorts. I felt his discussions around the topic were fascinating and immensely valuable but his conclusions were unconvincing. His two main publications on the topic differed so wildly that I felt here too he wanted them to serve this role more than the evidence warranted it. Now, while I still don't think his conclusions were correct, I do think his underlying hunch might have been correct on the basis of the distribution of the onsets (when reconstructed properly!). Unfortunately, no matter how convincing the argument, it's going to be difficult to prove conclusively.