Women's writing: dead or alive

« previous post | next post »

Article in BBC yesterday:

"Nüshu: China's secret female-only language", by Andrew Lofthouse (10/1/20)

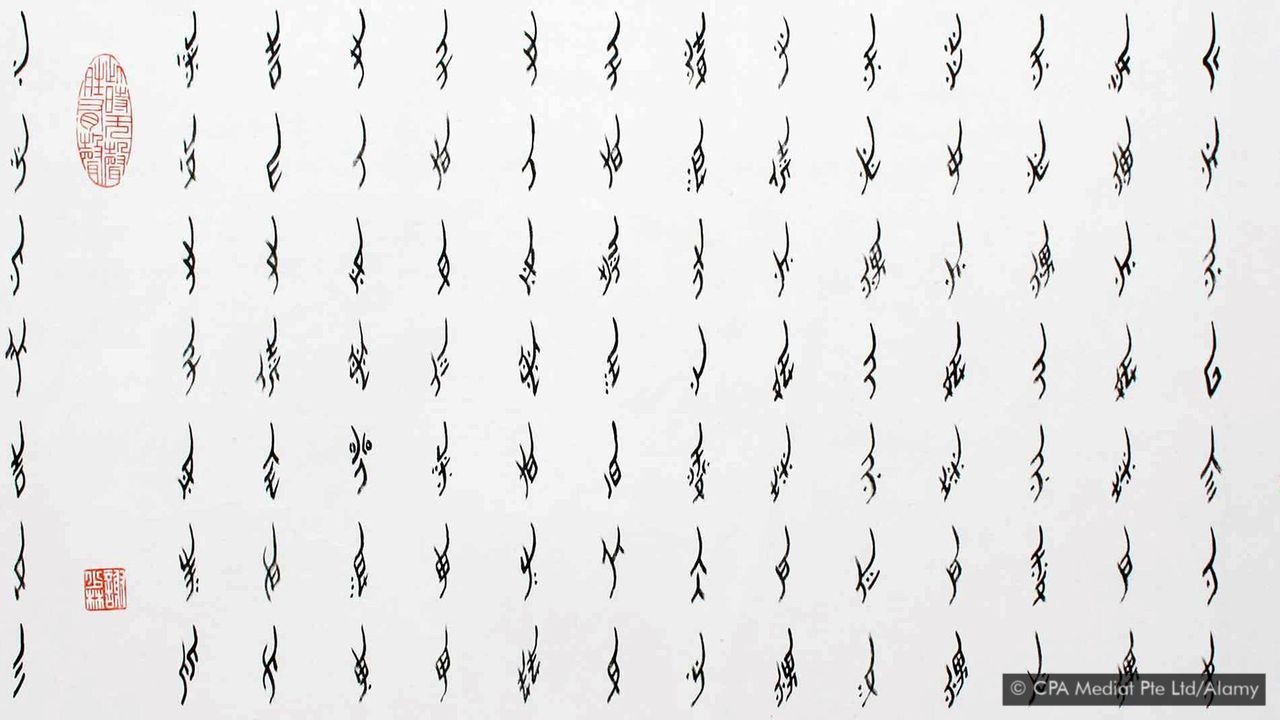

Here's what it looks like:

Nüshu is a women's-only script that was passed down from mothers to

their daughters in feudal-society China (Credit: CPA Mediat Pte Ltd/Alamy)

We have often written about Nǚshū 女書 / 女书 ("women's writing script") on Language Log and elsewhere (see "Selected readings" below). Indeed, I was the first person to bring a Nüshu specialist to America in the early 80s.

Here I will quote a few selected passages from the BBC article, which is rather long, and will critique them as I go. I will not repeat information the article provides that is readily available in standard sources elsewhere, nor will I focus on individuals who are quoted or described in it. The article is basically accurate and informative, but — as with many journalistic accounts of Nüshu, and Chinese writing in general — it romanticizes and exoticizes the script, and there are some errors and misinterpretations, mainly with regard to the relationship between writing and spoken language.

Throughout history, women in rural Hunan Province used a coded script to express their most intimate thoughts to one another. Today, this once-“dead” language is making a comeback.

VHM: How long is "throughout history"? Not really a "coded script" — simply a syllabary. When did it begin to live? When did it die?

…

Meaning “women’s script” in Chinese, Nüshu rose to prominence in the 19th Century in Hunan’s Jiangyong County to give the ethnic Han, Yao and Miao women who live here a freedom of expression not often found in many communities of the time. Some experts believe the female-only language dates to the Song dynasty (960-1279) or even the Shang Dynasty more than 3,000 years ago.

VHM: Nüshu could not possibly date back more than three thousand years to the time of the oracle bones, because it adopts simplifications of the standard Sinographic writing system which only occurred in the Song and Yuan (1271-1368) dynasties. And it is not a "female-only language"; it is a script that was used by small groups of women at a certain time and in certain places.

…

Remarkably, for hundreds or possibly even thousands of years, this unspoken script remained unknown outside of Jiangyong, and it was only learned of by the outside world in the 1980s.

VHM: Again, it could not possibly have been unknown for "thousands of years", and is likely around a thousand years old at most. I personally think it is no more than two or three centuries old. And what does it mean to call Nüshu an "unspoken script"? It was pronounceable and readable. People could record their feelings and sentiments in it. The could tell stories with it.

Today, 16 years after the last known fluent native “speaker” of this ancient code passed away, this little-known written language is experiencing something of a rebirth.

VHM: No need for the scare quotes on "speaker". She really spoke the language recorded by Nüshu, and it was not an "ancient code".

According to Puwei resident Xin Hu, Nüshu was once widely spoken in the four townships and 18 villages closest to Puwei. After experts found three Nüshu writers in the 200-person village in the 1980s, Puwei became the focal point for Nüshu research.

VHM: Once more, we see the confusion between language and script: "widely spoken", "three Nüshu writers".

…Xin began working as one of seven interpreters or “inheritors” of the language, learning to read, write, sing and embroider Nüshu.

VHM: It's not quite clear what is meant by "interpreters or 'inheritors'". If they are local, native speakers of one or another of the relevant topolects recorded in Nüshu, they are legitimate speakers of the language, though they may have had to learn Nüshu as a second script after Hanzi.

Nüshu is a phonetic script read right to left that represents an amalgamation of four local dialects spoken across rural Jiangyong. Each symbol represents a syllable and was written using sharpened bamboo sticks and makeshift ink from the burnt remains left in a wok. Influenced by Chinese characters, its style is traditionally more elongated with curved, threadlike strokes sloping diagonally downwards and was sometimes referred to as “mosquito writing” by locals because of its spindly appearance.

VHM: Fair enough.

…

“Some inheritors have learned from their grandmothers since they were young, like our oldest Nüshu heir He Yanxin, who is in her 80s,” Xin said. “People like it because they think this culture is very unique and want to learn and understand [it].”

VHM: Now I'm starting to get a sense of what is meant by "inheritors". Surely the author must be using the English equivalent for "jìchéng zhě 繼承者" ("heir; heritor; inheritor; successor"), a term that is common in Chinese cultural history studies. They are keeping the tradition going, though they may not be learning it in the traditional way their predecessors did.

But why the script originated and flourished in this remote part of China remains a mystery.

“I think it has to do with a constellation of factors that exist in many places in southern China; non-Han peoples, sinicization (the process of assimilating non-ethnically Chinese communities under Chinese influence), remoteness,” said Cathy Silber…

VHM: This makes sense. I suspect that similar female friendly scripts occurred in many places in China, not just in the south. What sets Jiangyong's Nüshu aside from other locally based, restricted, simplified scripts is that it was reported to the central government (as something suspicious and potentially subversive) and around the same time was noticed by researchers from outside (e.g., at Wuhan University) who wrote about it and publicized it. As such it gained recognition throughout China and even around the world, becoming commercialized and an object of tourism.

Liming Zhao, a leading scholar in the study of Nüshu, recently taught a course on the subject at Tsinghui University in Beijing.

VHM: That's Tsinghua, one of China's top universities. The fact that a course on Jiangyong Nüshu was taught there shows that there is little chance of it disappearing. It's part of the matrimony of human civilization, just as Classical Greek is.

…

“[Nüshu] has completed her historical mission – a cultural tool for lower-class working women who did not have the right to education to write languages,” Liming said. “Now she only leaves beautiful calligraphy, wisdom and brave spirit to future generations.”

VHM: Nüshu's historical significance is ongoing. In the days when it was a vital means of written communication on special subjects among small circles of women in Jiangyong County, it wasn't just lower-class working women who were illiterate, nearly all women found themselves in that condition. Literacy rates across society were very low, and for women they were almost nil. Even today, in rural areas of the PRC, despite what government statistics may claim, literacy outside urban areas is low, and for women in remote villages it is shockingly low.

Closing remarks

Jiangyong Nüshu is essentially premised on the simplification and stylization of standard Chinese characters. The women who created it chose one character to stand for one sound in their language (in contrast to standard Sinographic writing, where one sound may be represented by dozens or scores of discrete characters. In this way, the memory load on the users of the script was much reduced.

In addition, Nüshu adheres to the principle of what I call "rhomboidization", whereby the square shapes of Sinographs are tilted diagonally. Another noticeable feature of Nüshu is its exaggeratedly long, curved strokes to suit the particular medium they may be using, e.g., embroidery, one of the chief forms in which the script is practiced.

In some respects, Jiangyong Nüshu is distinctive, but it is not an utterly unique specimen of a script that was originally used primarily by women. Another is the Japanese cursive syllabary called hiragana, which was also known as onnade 女手 ("women's hand / writing"). Genji Monogatari (The Tale of Genji), one of the great novels of the world, written in the early 11th century by the noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu, was written in hiragana.

Hobos, doctors, plumbers, electricians, highway engineers, architects, mathematicians — all have their own symbols for writing in specific circumstances. When they wish to be extremely terse and convey highly specific, expert, insider information, people who are not privy to their practices cannot make hide nor hair of what these specialists have written.

Here at Language Log, I have paid particular attention to the jargony writing of Chinese restaurant workers. As I wrote in the conclusion to this post, "Chinese restaurant shorthand, part 5" (5/15/19):

It's interesting that, in this case, the phonophores of the two characters for the name of the dish serve as the phonetic annotation and shorthand for its sounds. As the women who invented nǚshū 女書 ("women's script") and various other phonetically astute individuals throughout Chinese history have realized, the Sinographic system has within it the potential to develop into a practicable syllabary.

Human writing develops more complex or simpler forms in accord with the needs of those who use it. In some cases, part of its purpose is to impress or even intimidate, in which case it will take on more elaborate and even ornamental forms. In other cases, writing is for sheer, bare bones practicality, in which case it is as lean and efficient as possible. Jiangyong Nüshu found itself somewhere in the middle between these two poles.

Selected readings

- "Women's Romanization for Hong Kong" (8/17/19)

- "The sociolinguistics of the Chinese script" (8/20/17)

- "Misogyny as reflected in Chinese characters" (12/25/15)

- "Women's words" (2/2/16)

- "Pinyin memoirs" (8/13/16)

- "Nüshu" Wikipedia

- "Chinese restaurant shorthand" (9/22/16)

- "Chinese restaurant shorthand, part 2 " (11/30/16)

- "Chinese restaurant shorthand, part 3 " (2/25/17)

- "Chinese restaurant shorthand, part 4" (4/21/17)

- "Chinese restaurant shorthand, part 5" (5/15/19)

- "Chinese restaurant shorthand, part 6" (6/17/19)

- "Hong Kong-specific characters and shorthand" (3/15/15), with links to relevant websites for restaurant shorthand characters

- "General Tso's chikin" (6/11/13), especially in the comments

- "Writing: from complex symbols to abstract squiggles" (6/11/19)

[h.t. Chau Wu]

Steven said,

October 3, 2020 @ 8:06 am

@VHM. Do you really want to call the adjective in the following passage "fair enough"?

"Nüshu is a phonetic script […]."

The laity uses it in a way that linguists do not. For us, phonetic contrasts with phonemic and morphophonemic whereas in the passage it seems to make no sense.

Or do I get that impression because I know nothing about Nushu?

A reader said,

October 3, 2020 @ 9:37 am

Using the word "matrimony" for "patrimony", accidental or not, is a lovely etymological wordplay in this context!

Victor Mair said,

October 3, 2020 @ 11:57 am

@A reader

Thank you. I did it on purpose, and with great delight.

Victor Mair said,

October 3, 2020 @ 1:34 pm

@Steven

"A syllabary is a phonetic writing system consisting of symbols representing syllables. A syllable is often made up of a consonant plus a vowel or a single vowel."

https://omniglot.com/writing/syllabaries.htm

Rodger C said,

October 4, 2020 @ 8:35 am

@Steven: These are journalists. They mean no more than "It's not a logographic script. You can infer the sounds by looking at it."

Barbara Phillips Long said,

October 4, 2020 @ 5:35 pm

In documents written in this script, is the vocabulary distribution different than contemporaneous documents in standard scripts? Is that because the script skews toward female interests and concerns, or simply because it is colloquial? The Women’s Words post talks about how some characters in Mandarin are male-centric, and that made me wonder if this script makes topics such as menstruation, childbirth, or tasks such as cooking or embroidery easier to write about.

Do later documents in the region use words or terms that first surfaced in documents written in the female script?

Kaleberg said,

October 8, 2020 @ 11:36 pm

I was just reading an article claiming that the Phoenician alphabet was derived by simplifying and phoneticizing Egyptian hieroglyphics, possibly in the Sinai where Egyptians established turquoise mines but hired local Canaanite workers who left intriguing alphabetic inscriptions using symbols borrowed from Egyptian writing.