Chinese restaurant shorthand, part 5

« previous post | next post »

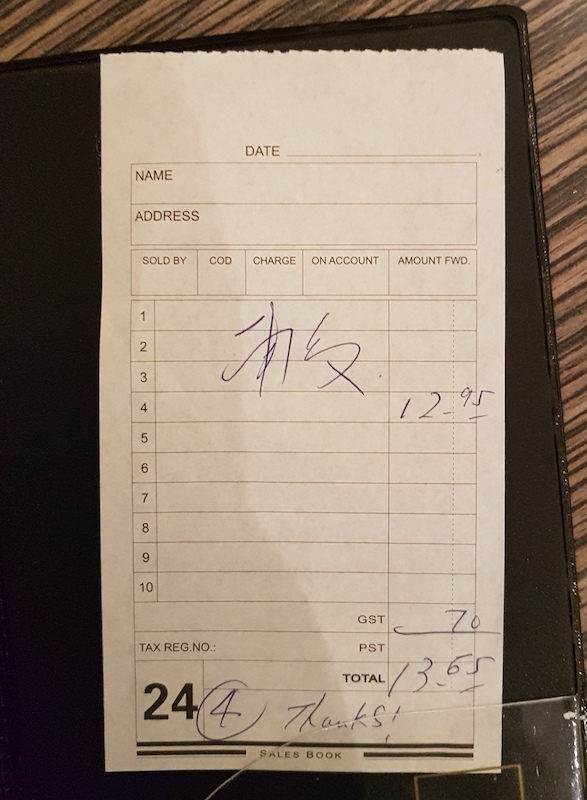

Subtitle: Phoneticization on an order from a Macanese restaurant in Vancouver.

Bruce Rusk sent in this prime example of extreme Sinographic shorthand, adding, "The geographic origin of the cuisine is a big hint to the document’s meaning…".

Although the cursiveness of the first character makes it somewhat difficult to decipher, it reads:

nánfǎn (MSM) / naam4fan2 (Cant.)

南反

"south anti- / counter- / turn over / rebel / revolt"

Disregarding the tones, the waiter has simply written down the sounds of the two characters used to write the name of this dish:

nǎnfàn (MSM) / naam5faan6 (Cant.)

腩飯

"brisket rice"

It's interesting that, in this case, the phonophores of the two characters for the name of the dish serve as the phonetic annotation and shorthand for its sounds. As the women who invented nǚshū 女書 ("women's script") and various other phonetically astute individuals throughout Chinese history have realized, the Sinographic system has within it the potential to develop into a syllabary.

Readings

"Chinese restaurant shorthand" (9/22/16

"Chinese restaurant shorthand, part 2 " (11/30/16)

"Chinese restaurant shorthand, part 3 " (2/25/17)

"Chinese restaurant shorthand, part 4" (4/21/17)

"Hong Kong-specific characters and shorthand" (3/15/15), with links to relevant websites for restaurant shorthand characters

"General Tso's chikin" (6/11/13), especially in the comments

[Thanks to Yixue Yang and Hilário de Sousa]

Bruce Rusk said,

May 15, 2019 @ 10:06 am

As the person who ordered and ate the meal in question, I can reveal that it was not nanfan/brisket rice. It's an even more interesting simplification: the dish was baked Portuguese chicken on rice, a Macanese dish consisting of piece of chicken and vegetables in a creamy sauce with a coconut milk base and spices (turmeric and cumin), topped with cheese and baked, served with rice. The mix of ingredients and techniques combines European, South Asian, and East Asian influences. You can find a recipe for one version here.

So the order doesn't read 南反 nanfan, it reads 甫反 fufan . This is short for 葡國雞飯 Puguo jifan ("Portuguese chicken rice")–Puguo being a short form of 葡萄牙 Putaoya, Portugal. On the order (but not the menu) 葡 Pu is further shortened to 甫 Fu, which is quicker to write. I'll leave it to Victor to tell us how this works in Cantonese, but in Mandarin pu is a rare alternate reading of 甫 fu, and more importabtly it's the phonetic component of the character, so it's clear on its own.

Victor Mair said,

May 15, 2019 @ 11:03 am

Wow!

Tricked me, Bruce, and lots of other people too!

I should have asked you before making the post, but my comments about the syllabary business still stand — in spades.

—–

反 = 飯 is the same as in the brisket rice I wrote about in the o.p. and in this earlier post

葡 pú (MSM) / pou4 (Cant.) — 1. grape; vine 2. short for Portugal

甫 fǔ (MSM) / fu2 [literary], pou2 [colloquial] (Cant.) — 1. just (now); only 2. one's courtesy name

—–

Fascinating!

I learn something new every day.

多謝 duōxiè (MSM) / do1ze6 (Cant.) — many thanks!

Hilário de Sousa said,

May 15, 2019 @ 10:50 pm

Ah, tricked me as a 甫人, and a 南人… I'm embaraçoso/瘀爆皮…

Victor Mair said,

May 15, 2019 @ 11:40 pm

@Hilário de Sousa:

I greatly appreciate your response as a 甫人 and a 南人.

Lian-Hee Wee said,

May 16, 2019 @ 8:18 am

Hi!

I thought to share this paper published in the the journal "Hong Kong Studies" with you.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327248291_Principles_of_the_Hong_Kong_Kitchen_Shorthand

There's also a short story version recently published in "World Literature Today".

https://www.worldliteraturetoday.org/2019/spring/hong-kong-food-runes-lian-hee-wee

Best,

Lian-Hee

Faith Jones said,

May 16, 2019 @ 11:00 am

Vancouverites want to know… what restaurant?

Katelyn said,

May 17, 2019 @ 9:14 am

These are mostly informal contexts. 女書, as mentioned on the Wiki article, is mostly used to write 湘南土話. 土話 is a Chinese term used to refer to regional colloquial terms or regional spoken words. These are usually never written down, but if "written down", the people may borrow Standard Chinese characters and associated Standard pronunciation to transliterate the spoken word. The character combination will usually mean nonsense in Standard Chinese.

The official Simplified script was intended to make Chinese writing easier. Well, the people decided to simplify further. My aunt, living in China as a native, once told me that there are now some characters used inappropriately in big displays; and she used them herself.

Instead of writing 盒, she would write 合 because they sound identical to her. So, this 合 has come to represent this 盒. Instead of writing 餐, she wants to write 歺 but her cell phone does not recognize that character so she ends up using 攴, and now this 攴 is used to represent 餐 in actual public places too, probably because a lot of people have the same problem.

Meanwhile, TV captions and published literature are still written in the proper Standard Chinese form.