Chinese restaurant shorthand, part 4

« previous post | next post »

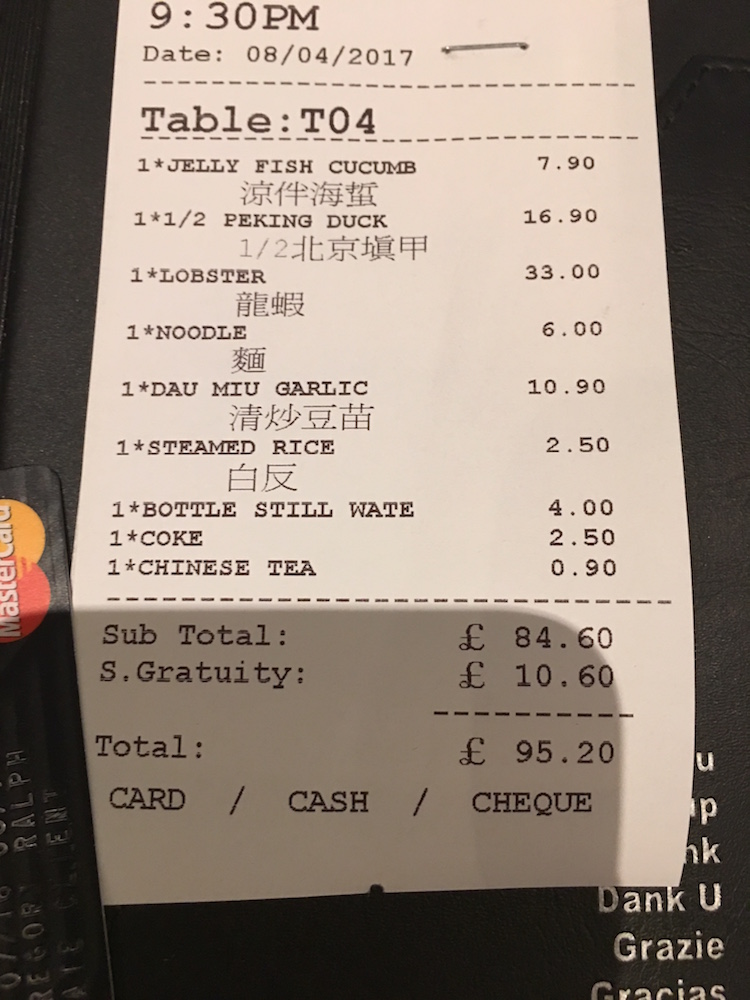

Spotted by Greg Ralph in a London restaurant:

I will give each item on the receipt in both simplified and traditional characters, followed by explanatory notes:

liángbàn hǎizhē 凉伴海蜇 / 涼伴海蜇

Note: bàn 伴 ("partner; companion; accompany") has been substituted for bàn 拌 ("mix [in]; blend")

—

Běijīng tiánjiǎ 北京填甲 / 北京填甲

Note: the only native speakers of Sinitic languages to which I showed this who could understand why it means "Peking duck" were Cantonese speakers, but not even all the Cantonese speakers who saw this could understand it.

tián / tin4 填 ("stuff; fill")

Cant. gaap3 甲 ("armor") is shorthand for aap3 鴨 ("duck" — same final and tone)

Several of my respondents mentioned that they had received a "tiányā shì jiàoyù / tin4aap3 sik1 gaau3juk6 填鴨式教育" ("stuffed duck style education"), which they said is Chinese style education where things are just crammed down students' throats.

The standard way to say the name of this dish in Mandarin is Běijīng kǎoyā 北京烤鸭 ("Peking roast duck").

For additional notes on why Peking duck is referred to in Cantonese as "stuffed / filled / force-fed", see the appendix at the bottom of this post.

—

lóngxiā 龙虾 / 龍蝦

Note: It's ironic that they didn't use shorthand versions for these complicated characters, especially the first.

—

miàn 面 / 麵

Note: The full disyllabic form of this word in is miàntiáo / min6tiu4*2 面条 / 麵條.

—

qīngchǎo dòumiáo 清炒豆苗 / 清炒豆苗

Note: This is stir-fried / sautéed pea sprouts / shoots.

—

báifǎn 白反 / 白反 (lit., "white reverse")

Note: This stands for báifàn 白饭 / 白飯 ("white rice").

Earlier posts on this subject:

- "Chinese restaurant shorthand " (9/22/16)

- "Chinese restaurant shorthand, part 2 " (11/30/16)

- "Chinese restaurant shorthand, part 3 " (2/25/17)

It's intriguing to note that these shorthand versions persist even in the days of tablet or iPhone ordering, when it would presumably be no harder to select the "right" character than the "wrong" one from a preset menu of options. It seems that Cantonese waiter shorthand has made the jump from handwriting to the digital realm.

————

Appendix

Note on the force-feeding of ducks and geese from Wikipedia:

Foie gras (/ˌfwɑːˈɡrɑː/, French for "fat liver") is a luxury food product made of the liver of a duck or goose that has been specially fattened. By French law, foie gras is defined as the liver of a duck or goose fattened by force-feeding corn with a feeding tube, a process also known as gavage. In Spain and other countries outside France it is occasionally produced using natural feeding. Ducks are force-fed twice a day for 12.5 days and geese three times a day for around 17 days.

Foie gras is a popular and well-known delicacy in French cuisine. Its flavor is described as rich, buttery, and delicate, unlike that of an ordinary duck or goose liver. Foie gras is sold whole, or is prepared into mousse, parfait, or pâté, and may also be served as an accompaniment to another food item, such as steak. French law states that "Foie gras belongs to the protected cultural and gastronomical heritage of France."

The technique of gavage dates as far back as 2500 BC, when the ancient Egyptians began keeping birds for food and deliberately fattened the birds through force-feeding. Today, France is by far the largest producer and consumer of foie gras, though it is produced and consumed worldwide, particularly in other European nations, the United States, and China.

Gavage-based foie gras production is controversial, due mainly to the animal welfare concerns about force-feeding, intensive housing and husbandry, and enlarging the liver to 10 times its usual volume. A number of countries and jurisdictions have laws against force-feeding, and the production, import or sale of foie gras; even where it is legal, a number of retailers decline to stock it.

————

[Thanks to Abraham Chan; Tang Pui Ling, Yixue Yang, Jinyi Cai, Mandy Chan, Judy Weng, Carmen Lee, Alan Chin, Norman Leung, and Bob from Detroit]

John Swindle said,

April 22, 2017 @ 1:10 am

Cantonese aap3 for gaap3 is only a little closer than, for example, Mandarin jiǎ for yā, but only Cantonese speakers could understand it. So maybe 甲 for 鴨 is more a matter of substituting a similar-looking but simpler character, and non-Cantonese speakers don't understand it because they don't call the dish stuffed duck. Maybe if it said jīng kǎojiǎ 京烤甲("capital roast armor")?

Chris Godwin said,

April 24, 2017 @ 3:22 pm

Re force fed duck – there's a fascinating account in a book I read a few years ago – sorry forget the title, it dealt mainly with gangsters in Xiamen – about a single small town in Guangxi which produces more foie gras than the whole of France. The main farmer professed to enjoy a huge slab of the stuff for his breakfast. A striking example of the gap between the n China between sudden wealth, and taste.

FionaPan said,

April 26, 2017 @ 8:22 am

Looking through you posts on Chinese restaurant shorthand with details , it keeps my eyes on this phenomenon. It’s really an intriguing topic.

In your first post of this topic, you showed the receipt from Ting Wong restaurant with illegible scrawl on it, writing cha1jia3fan3 in Chinese character. It did make me surprised. Not until finishing reading your post did I realize what the words really mean, even though I am a Chinese. Hahaha.

From my point of view, there's no doubt that the reasons behind these shorthand in Chinese restaurants are various, but I think the following factors must involve. Efficiency plays an important role here. Maybe I'm not know the real situation in the foreign countries that well. But in Chinese restaurants, people sometimes make a rush in meals. Waiters therefore need to write down orders as soon as possible to improve the efficiency. This kind of approach is used either in Hong Kong or the rest regions in China.At the second place, it is about Chinese regions culture. Back to you posts, what you showed are probably from Hong Kong-specific characters and shorthand. Most of Chinese call mian4面 as mian4tiao2 面条. "Ting Wong Restaurant" would be another strong evidence. In Cantonese, we used to call it "ting" than "tian" in Mandarin.Seeing your latest post of Apr.21, it occurs to me that lack of education should be taken into consideration as well. From the printed receipt, we can see shorthand like fan3 反 still used as the substitute for the correct one, fan4饭. It set me thinking why they still use the shorthand with no need of writing. It’s reasonable to assume that undereducated Cantonese waiter make these "wrong" shorthand pervade to the digital realm.

Anyway, behind this phenomenon, there lays lots of things we can dig into. Thank you for keeping posting these to us! Please feel free to contact with me. :)