A new and useful dictionary of Sinographs

« previous post | next post »

We have often noted how much easier it is to learn Chinese now than it was just ten or twenty years ago. That's because of all the new digital resources that have become available in recent years:

- "The future of Chinese language learning is now" (4/5/14)

- "Learning languages is so much easier now" (8/18/17)

Of course, there are a lot quick fix programs out there, and one should be wary of them:

- "Duolingo Mandarin: a critique" (11/21/17)

- "Chineasy? Not" (3/19/14)

- "Chineasy2" (8/14/14)

But every so often a really good resource comes along, and I should like to introduce one such in this post.

It's The Outlier Dictionary of Chinese Characters (ODCC). Here's a brief description:

A dictionary for learners of Chinese who want to learn characters more efficiently, without being distracted by nonessential information. Unlike other products for learning characters, the ODCC is based on the most up-to-date academic research on the Chinese writing system and teaches Chinese characters as they actually work.

ODCC covers the 1500 most frequently-used characters (Traditional and Simplified) — enough for full-fledged literacy in Chinese. More entries will be added in the future.

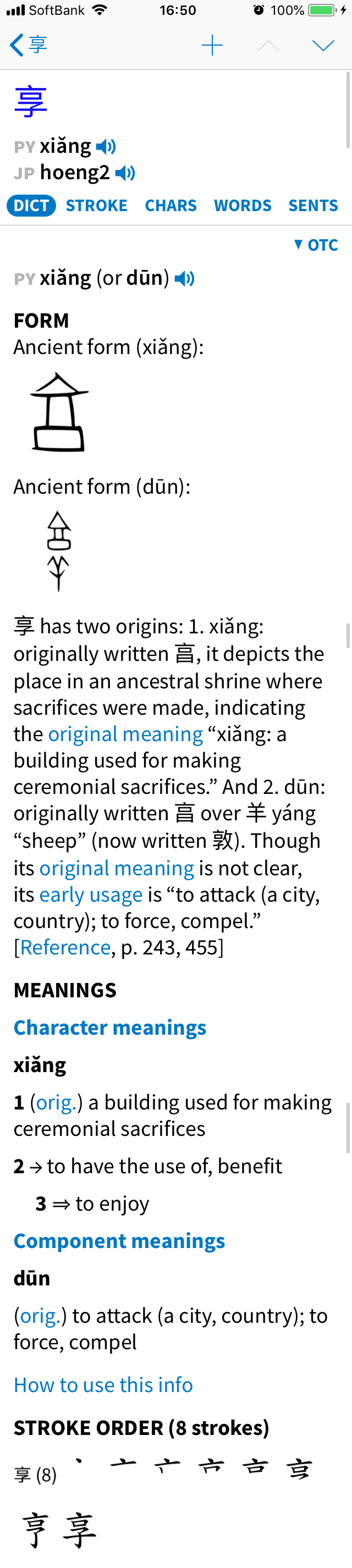

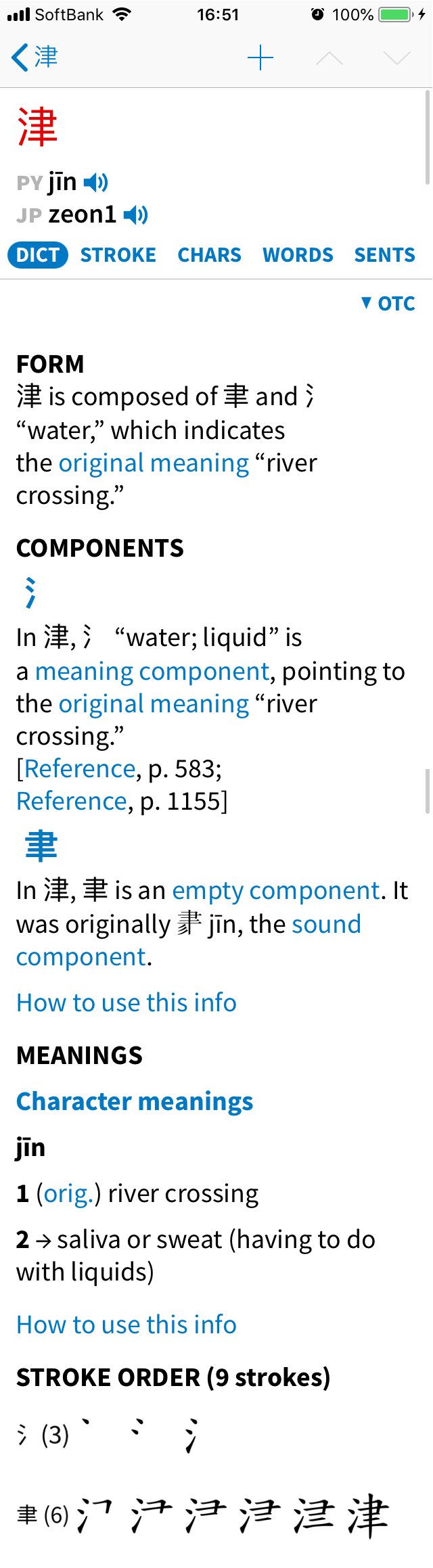

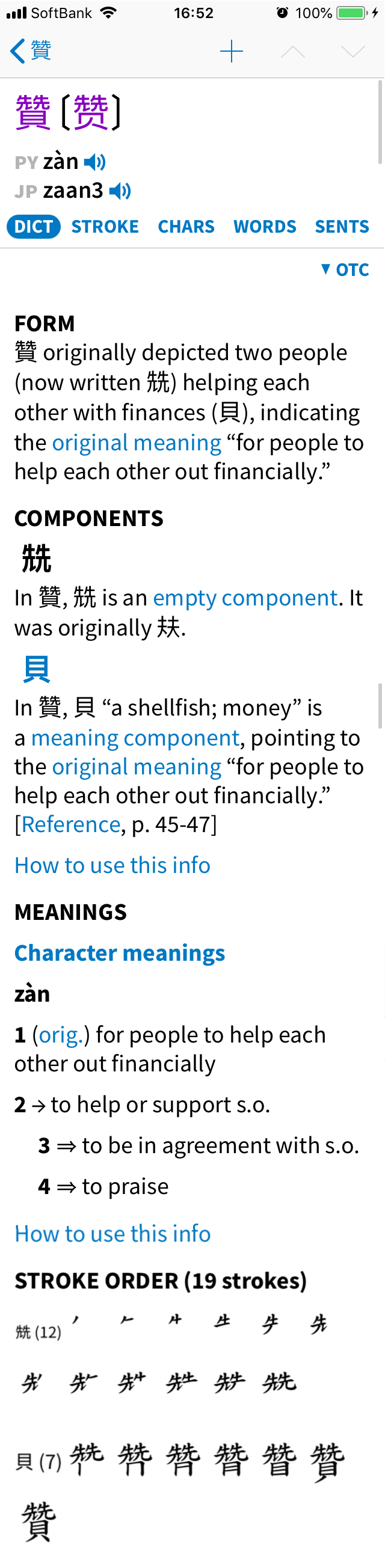

For each character, the dictionary contains:

– Character form explanation, so you understand why each character looks the way it does. An ancient form is included for characters which were originally pictographic, which function as semantic components, or which cannot be broken down into components.

– Component breakdown and analysis: what are the functional components in the character, and how do they function?

– Mandarin pronunciation according to PRC and ROC standards. Cantonese pronunciation.

– Meaning chart showing the logical relationships among the character’s different meanings — this helps students remember the meanings more easily via association.

– Stroke order diagram (simplified according to PRC standards; ROC for traditional).

– Citations for the academic publications which most inform the analysis of the

character in question.

Benefits:

– Shows how Chinese characters actually work.

– Clears up confusion caused by similar-looking components.

– Helps the student make intelligent predictions about characters they haven’t even

learned yet.

– Helps the student remember how to write characters.

– Opens a whole new world of sound connections between characters.

Expert assessments:

• “This is not just some ordinary Chinese learning app, like you see flooding the web right now, but it's really a very powerful and useful comprehensive tool for the understanding of Chinese characters.”

—Prof. David Moser, Associate Dean at the Yenching Academy of Peking University in Beijing

• “They are building a dictionary that enables a strong understanding of the system of functional components behind characters, while also enabling curious learners to go as deep as they want in their character studies. This is exactly how it should be done.”

—John Pasden, AllSet Learning (and former ChinesePod host)

Student reactions:

• “I bought this. It has helped me recognise and even pronounce characters I have never seen before thanks to my recognition of patterns from the explanations.”

—Soroush Torkian (Canada)

• “After a lot (really a lot) of failed tests with different books, apps and methods, the only way that the hanzi sticks in my mind is ODCC's brief, concise and REAL explanation!”

—Alessandro Agostinetti (Italy)

• “This project is exactly what i was wishing for since i started learning Chinese with pleco years ago”

—Wieland Schultz (Germany)

Here are screen shots of the treatment of three sample characters:

ODCC is a Pleco add-on; it's available for purchase within Pleco itself or via Outlier's website. Similarly, the Japanese version will be an add-on for the dictionary app Japanese by Renzo, and once it's released it will be available both within the Japanese app and via Outlier's other website (it's currently available for pre-order).

The Chinese version of the dictionary has been released, and it contains full entries for roughly the 1,500 most common characters, plus about 300 semantic components. It covers the characters in HSK (Modern Standard Mandarin proficiency test) levels 1-4 and most of HSK5 (out of a total of 6 levels). Outlier will continue to expand their dictionary in the future, but it's already enough to carry learners well into intermediate territory, which covers the bulk of Chinese characters occurring in typical texts that one might encounter in daily usage.

The creators of ODCC came to see me about five (maybe more) years ago, and I was convinced already then that they would eventually produce something of superior quality, so I supported them as much as I could. What impressed me most about the members of the team was that they were not being dilettantish about their project, but were approaching it with the full knowledge that it would not be an easy task. They were taking serious philology courses at National Taiwan University and elsewhere, and were becoming intimately acquainted with the actual history of Chinese character development, not some fanciful tales based on popular folk "etymologies". Instead, they were familiarizing themselves with the nitty-gritty of the progression of individual characters from the stage of Oracle Bone Inscriptions (ca. 1200 BC) to Bronze Inscriptions (roughly first half of the first millennium BC) and then to the Seal forms (latter half of the first millennium BC). It is only when one understands the changes that occurred in each of these stages that one can be clear about the underlying meaning of the individual characters, and that is one of the beauties of ODCC. Although the editors' explanations of the origins and meanings of the Sinographs in their dictionary are written in simple, straightforward language, they are based on a wealth of learning, and that includes a correct understanding of the nature and construction of the characters and their components — a rare commodity in Chinese lexicography.

Chris Button said,

October 19, 2018 @ 10:18 pm

Looks interesting. I'm curious as to why they didn't assign 贊 to its apparent phonetic 先 ?

Annie Gottlieb said,

October 19, 2018 @ 11:08 pm

It might also be easier because of Rupert Sheldrake's theory of morphogenetic fields, which would suggest that the more (in numbers) Westerners learn Chinese, the easier it should become for Westerners to learn Chinese.

AntC said,

October 19, 2018 @ 11:10 pm

Thank you Victor, this sounds like a splendid initiative. But I continue to be confused by your posts about Sinographs

full entries for roughly the 1,500 most common characters … the bulk of Chinese characters appearing in typical texts

And the 1,500 includes "a building used for making ceremonial sacrifices". Would that correspond to English shrine? temple? church?

I've learnt enough that I should not confuse 'character' = word; but more like 'character' is building block for a word. Never the less, if we took the 1,500 most common English words, would that include shrine/temple/church?

That seems on a par with the confusion in Ogden+Richards 'Basic English': a word might appear common because it encompasses several homonyms (or more likely homographs in the case of O+E), but each separate sense is not common enough to justify inclusion.

So the ODCC, having decided to include some character, is then compelled to give every meaning for it, along with the history of the character(?), even if the modern character is a merger of what were historically distinct(?)

Ash said,

October 20, 2018 @ 12:19 am

@Chris Button:

Basically, in paleography, there is a lot of 音近可通 and depending on the author, what constitutes 音近 is very broad. I tend to take a more narrow stance and put stricter requirements on what can be considered 音近. Looking at the data for this particular case (the OC reconstructions and MC transcriptions are Baxter & Sagart and Baxter 1992 respectively):

兟 *sər (文部) > srin (所臻切)

贊 *tsˤarʔ-s (元部) > tsanH (則旰切)

The 聲母 and 韻尾 are obviously no problem, but having a differing main vowel always gives me pause. There are cases of 通假 between 文部 and 元部, so it's not impossible that 兟 is the phonetic (via the process of 聲化).

Ash said,

October 20, 2018 @ 12:35 am

@AntC:

享 is a fairly common character appearing in the common word 享受 xiǎngshòu "to enjoy." It also appears as a component in other characters.

And, no, we are not compelled to give every meaning of each character. We only give the original meaning and the meanings that are commonly used in modern Chinese. We give the fewest possible of those possible in order to reduce the learning burden, but enough such that the learner still has a firm grasp on how the character is used in modern Chinese.

It is, however, necessary to include the original meaning of the character, regardless of whether it's used in modern Chinese. That is the only meaning tied directly to the character's form. The purpose is to answer the question "Why does this character look like that?" And the original meaning is a necessary part of the answer to that question.

Victor Mair said,

October 20, 2018 @ 3:54 am

@AntC

"I continue to be confused by your posts about Sinographs"

All of them? Most of them? Some of them? How so?

GH said,

October 20, 2018 @ 4:56 am

Congratulations on the release, Ash and team!

(I assume from the post that the ODCC has recently been released.)

I've found a pinch of etymology to be very helpful in studying foreign languages, as it aids in seeing the relationships between different words and different senses and putting them into a coherent, meaningful story, so I have no doubt that a similar resources for Chinese characters will be extremely valuable for learners.

Chris Button said,

October 20, 2018 @ 7:21 am

@ Ash

So firstly, congratulations on what looks like a wonderful tool! I very much appreciate its pedagogical aim so my comments below are intended purely in terms of good scholarly discussion rather than to pick holes in your work which probably don't necessarily warrant inclusion anyway given the dictionary's broader purpose (so sorry if I seem like an annoying nit-picker!)

先 (here via 兟) and 贊 demonstrate the underlying "ə/a" ablaut relationship that permeates the whole Chinese lexicon. There are countless examples of this ablaut within phonetic series of characters and between etymological related words (whether belonging to the same phonetic series or not). While Baxter and Sagart's system is very good at highlighting rhyming practices in Old Chinese in terms of surface phonetics, it suffers terribly at finding such relationships at a deeper phonological level and as a result misses many of them. As far as I am aware, the form 賛 with 㚘 is simply an abbreviated form of 贊 with 兟 and so strictly speaking you shouldn't really assign 㚘 an original role even if it makes for a nicer (and more useful in terms of your dictionary) "etymological" account.

Philip Taylor said,

October 20, 2018 @ 8:34 am

Sigh. Extraordinarily useful I have no doubt, for those who use IOS and/or Android on their smart'phones, but what about we dinosaurs who prefer to use real computers running Windows or Linux ? Is there anything better than Zhongwen.Com, which I first used in or around 1998 when Rick Harbaugh published 中文字譜 Chinese Characters : A Genealogy and DIctionary, a very useful reference work which would have benefited enormously from being published in a larger format. ?

CPC said,

October 20, 2018 @ 10:04 am

I find it frustrating when paid-for app take advantage of freely available resources (from a quick glance, the stroke order diagrams are likely from Wikipedia), without contributing back. Hopefully they'll make at least some of their data freely available.

Michael Love said,

October 20, 2018 @ 10:54 am

Pleco person here.

@Philip Taylor – you can run our Android app in an emulator on Windows or Linux; there’s a long thread about that at https://plecoforums.com/threads/google-arc-welder.4590/. On newish Chromebooks you can pretty much just run Android apps without having to install anything (they ship with the Play Store built in). We also expect to have a Mac version of Pleco next year thanks to Apple’s “Project Marzipan” letting iOS apps work easily on Mac.

@CPC – I believe Outlier’s stroke order diagrams were their own creation. The stroke order diagrams in Pleco itself were licensed from Wenlin. And as far as “giving back” in general, we released an entire open-source Cantonese dictionary at cantonese.org; we also forward along corrections to other open-source projects like CC-CEDICT when we find them (or get them from users).

Philip Taylor said,

October 20, 2018 @ 2:26 pm

Michael Love ("Android app in an emulator") — thank you: very useful information, and much appreciated.

Jonathan Smith said,

October 20, 2018 @ 10:52 pm

@AntC, etc. Also arguably a nitpick: the term "original meaning" as employed by the ODCC creators apparently means "that thing (etc.) which a character was first designed to represent." Thus the explanation that "享" depicted a ritual edifice. But equally important and quite different is the notion of "the word(s) which a character was first employed to write." On this more important front, from the beginning the character "享" was not to my knowledge used to write a noun like 'shrine' or similar at all, but rather a verb related to giving offerings to spirits (compare the word written 饗). This is the information which renders the modern vocabulary comprehensible. The confusion of these two notions — esp. the implication that characters must naturally at some primeval stage have been used to write the names of exactly those things which they first depicted — is an unfortunate hallmark of much traditional paleography.

Peter Taylor said,

October 21, 2018 @ 12:42 am

Looks good but why can it only be used through Pleco? When I buy the Outlier dictionary I shouldn't be forced to change my dictionary app too.

Minhv said,

October 21, 2018 @ 1:28 am

@Chris Button

I checked a few independent sources (deliberately excluding the one Outlier references), and they all say that the form 賛 is the original shape of the character. The change from 賛 to 贊 is a Han Dynasty shape corruption, which could potentially be from a phoneticisation process.

Whatever the etymological connection (if any), the written form of 賛 was unrelated to 先/兟 at the conception of the character.

~flow said,

October 21, 2018 @ 4:40 am

Certainly, 享=亯=𠅖 alongside with 高喬京倉 and so on belongs to a group of characters that depict 'high rises', 'towers'. Even if in modern usage 享受的享 doesn't betray its original meaning, it still bears mentioning, for the purpose of the education of the learner, that while today we think of it as 'enjoyment', 'sharing' or 'partaking', it started out as 'ritual edifice'. The older meaning seems to go along the lines of 'sacrifice', which sounds reasonable to me. I have to agree with @Jonathan Smith that it is important to point out both what a character (used to) depict on the one hand and what it used to be used for on the other (and what it stands today for on the third hand). A good number of modern morphemes (e.g. zu 'enough' , xiang 'resemble') are written with characters (足, 象) that depict unrelated objects and were chosen just for their similar sounds (of the words for things they depict), but the line is sometimes hard to draw between the arbitrary connection between, say, 象 and 'resemble' on the one hand, and the underlying (etymological) roots of 享 (depicting a 'temple' building, hence) '(to) sacrifice' > 'to enjoy'.

If I had some criticism to offer, it would be that, as the screenshots above do show, the very limited screen space on mobile devices defy any attempt of presenting any subject in depth at all; the harsh limitations of a screen that is a mere few inches wide and high (and that goes dark as soon as the battery exhausts as it is prone to do each day without charging) are such that the smart phone can deliver good services as a prompter for the forgotten word or fact or to point out whether to turn left or right next.

As such—are there plans to publish the findings of the Outlier Linguistics group in paper form?

~flow said,

October 21, 2018 @ 4:43 am

—finishing off the sentence—"that the smart phone can deliver good services as a prompter for the forgotten word or fact or to point out whether to turn left or right next", but is of doubtful value when misunderstood and being used in the place of a good dictionary or textbook.

Chris Button said,

October 21, 2018 @ 1:50 pm

@Minhv

賛 is indeed old. In terms of attested examples it is even seemingly slightly older than 贊, albeit at a comparable time depth, so I cannot completely rule out an original 賛. However, it is not that old, and in want of earlier evidence, a phonetic account with 贊 seems preferable to any notion of a very late "huiyi" (i.e. combination of two people + money) which was not really a formative process in the Chinese script beyond the earliest inscriptional forms in which we have no evidence for 贊/賛. Having said that, I do find the use of 兟 rather than simply 先 somewhat perplexing since the latter would logically have sufficed while the former is not a real graph so perhaps some iconic representation was going on here after all? The one thing we can say with pretty much certainty is that 先 via 兟 is phonetic in 贊 regardless of the earliest (perhaps as yet unidentified) form of the character.

Chris Button said,

October 21, 2018 @ 10:27 pm

@ Minhv

Further to the above, I've now looked a little more closely and can't seem to find any evidence that 賛 is older than 贊. The former just seems like a rare variant form of the latter as would be expected. You mentioned some sources above so I was wondering on what they are basing such an assertion?

@ Jonathan Smith

I think your final comment there is a little harsh, although I absolutely concur with your point above about the importance of bringing in word family relationships like 饗. In my humble opinion, the biggest problem with traditional palaeography is the same as that with Old Chinese reconstruction: rarely do the "top" scholars seem to be well-versed in the intricacies of both fields.

Minhv said,

October 22, 2018 @ 12:00 am

@Chris Button

The team at Outlier is probably able to give a better response, but I'll quote the following resources.

Firstly, Outlier's own reference:

杜忠誥《說文篆文訛形釋例》 – I don't have access to this myself, but the title indicates that it deals specifically with *Shuowen* Lesser Seal script shape corruptions.

Then, the ones I checked:

黃德寬《古文字譜系疏證》 – This title suggests that 㚘 is actually a phonetic component, but also states that 兟 is a shape corruption from 㚘. 㚘 is usually considered as an older variant of 伴, so it is plausible that it plays a phonetic part in 贊.

李學勤《字源》 – This title is considered somewhat less reliable, but says roughly the same thing.

Both these latter two titles trace the earliest form of as 賛, found in samples dating to the Qin Dynasty, and consider 贊 as a shape corruption traced to the Han Dynasty. Since Shuowen is a Han Dynasty title, I suspect that 杜忠誥《說文篆文訛形釋例》 says the same thing.

Ash said,

October 22, 2018 @ 3:01 am

@Chris Button:

I agree that many traditional paleographers are stuck using a traditional understanding of phonology, but that doesn't mean they're wrong about everything. They have a deep understanding of form evolution and of the classics (i.e., semantics) as well as syntax, semantics of oracle bone and bronze inscriptions, not to mention excavated texts. Personally, I've been trained a lot in both the traditional system and in modern historical linguistics. I'm very familiar with Baxter & Sagart, Baxter 1992, 鄭張尚芳、金理新 and more traditional scholars like 李方桂、董同龢、陳新雄、王力.

Conversely, a lot of scholars that do phonological reconstruction are not very familiar with paleography. That can't be said of Dr. Baxter, however.

And when it comes to morphological markers in OC, I totally agree with you. However, the field itself is still pretty young. I'm totally convinced that there were things like prefixes, suffixes, etc. But, that doesn't mean I believe each instance of someone saying they found a prefix, suffix or whatever.

Ablaut is not out of the question either and in the case we're talking about, like I said above, it's not impossible. However, I would have to see more than the possibility of it being ablaut before I change my mind. I'd have to see the morphological purpose of the ablaut in some systematic way. And just as a point of information, I don't base my conclusions on a single scholar, either paleograpically or phonologically.

Ash said,

October 22, 2018 @ 3:11 am

@Minhv:

杜忠誥《說文篆文訛形釋例》:

This book is basically about how to test whether the Shuowen's form explanation for a given character is correct or not. It's also about showing the various types of corruption that can occur. I actually took this class from 杜忠誥 himself. Phonologically, he tends toward the traditional analysis, but he's very systematic in his study of form evolution. He also tries to take in as much data as possible (that's one of his main points in this book — you can't tell by looking at one or two forms. You need to look at as many as you can get your hands on so to speak).

李學勤《字源》:

This can be a good resource, depending on the scholar who did the entry you're looking at. I find the quality to vary radically depending on who wrote a given entry. When I use this resource, I always include the scholar's name in my notes. Some of them, if I see their name, I don't even bother reading the entry.

We also look at 黃德寬《古文字譜系疏證》 and the closely related 何琳儀《戰國古文字典》.

Chris Button said,

October 22, 2018 @ 10:25 am

@ Ash

Thanks for the comments. I'm not sure if all of them were supposed to be intended for me, but I'll respond as best I can:

I was actually trying to stand up for traditional palaeography – I guess that didn't quite come across! I have a huge amount of respect for all that has been done. My comment was really a desideratum of sorts and looking at it in the light of the morning was unwarranted given that my views on OC phonology are inspired by (but don't exclusively follow) Pulleyblank which outside of some very influential areas doesn't always get the respect it deserves in my opinion.

I was actually really only here referring to the earliest inscriptions and should have been more precise in that regard.

Ok so I don't think I said that about morphological markers! While I have a tremendous amount of respect for Baxter & Sagart's work and love to read it, I do respectfully disagree with a lot of it and am certainly not on board with how they reconstruct much of their supposed morphology. My reconstructions are far simpler in that regard.

The problem with "huiyi" explanations is outside of the earliest inscriptions they just don't hold up even if they do provide nice mnemonic devices (and In fact even some of the earliest ones like 好 aren't even cases of "huiyi"). Once "huiyi" graphs had become entrenched as "xiangxing" and viable entities for the production of "xingsheng" (i.e. using phonetic components), it would have been unlikely for new characters to be systematically created (i.e. outside of a few isolated cases) irrespective of their pronunciation.

My dictionary (I think I mentioned it to you in an earlier post) is slowly putting the evidence together for the "ə/a" alternation across the whole OC lexicon. However, although I use the word "ablaut", it might not be the right word since the evidence is entirely phonological and I cannot identify any morphological function (Pulleyblank tried with a few isolated examples, but I just don't buy it). Whatever the function was (if any – it could just be a property of language with schwa being the default "syllable" and /a/ just the default sound when you open your mouth wide at the dentist for example), there is certainly no evidence now for any role. To take a random example, what possible role could it play in differentiating clearly related words like 齒 *kɬə̀ɣʔ "tooth" and 杵 *kɬàɣʔ "pestle" ?

Chris Button said,

October 22, 2018 @ 10:26 am

@ Ash & Minhv

For what it's worth…

https://ctext.org/pre-qin-and-han?searchu=%E8%B3%9B&reqtype=stats

https://ctext.org/pre-qin-and-han?searchu=%E8%B4%8A&reqtype=stats

Ash said,

October 22, 2018 @ 11:30 am

@Chris Button:

Yeah, I'm actually not much of a fan of huiyi explanations either. Though, that isn't to say they didn't exist (I've read Boltz's paper on that and found some, but not all, of his examples convincing). I think you also need to take the difference between 以形會意 and 以義會意 into account. The former being like 祭, and the later being like 尖. 以形會意 appear early on and there are relatively more of these, compared to 以義會意, which appear really late and though there are very few of them, most modern "folk etymologies" reinterpret basically any and all characters as this type (like 美 being explained as "big sheep" or whatever).

I don't really even take 六書 into account when doing an analysis. I'm more concerned with finding out what the functional components are and figuring out their function.

I'm interested in learning more about the ablaut (or whatever we should be calling it). My interest in OC morphology is largely due to trying to understand sound variation within xiesheng series. Is there anything you can recommend to read on that?

Minhv said,

October 22, 2018 @ 7:06 pm

@Chris Button

There might be a procedural error in trying to use frequency occurrences of 賛 vs 贊 in a digital database like ctext as evidence, for two reasons: (1) Most of these classical texts are actually republications in later dynasties, so old shapes wouldn't have been preserved, and (2) the digitisation of texts in ctext differs in purpose to digitisation of texts for a paleographer; the former is concerned with legibility to people who study Chinese literature (so will not hesitate to use modern shapes as replacements even if they're not faithful), while the latter would be absolutely concerned with the original shapes of the characters.

This is a bit like finding occurrences of 认 (https://ctext.org/pre-qin-and-han?searchu=%E8%AE%A4&reqtype=stats) and using this as evidence that 认 existed since the Pre Qin and Han era.

The only reason why 賛 even exists as a digital character in the common Unicode block (U+8CDA) is because it is also a Japanese Shinjitai. Similar low counts of Shinjitai shapes like 黒, 薫, etc. (as opposed to their orthodox counterparts 黑, 薰) are also apparent in ctext, even though one frequently finds Song to Ming era texts with that shape. Rarer, older shapes that are not revived Simplifications used in some Han-character using region are either not in Unicode at all, or in some Unicode-ext block and can't be rendered properly using most fonts, so text digitisation efforts for non-paleographic purposes will normally avoid those shapes whenever possible.

Jonathan Smith said,

October 22, 2018 @ 7:09 pm

In terms of sheer breadth of knowledge, us young 'uns and more specifically us Westerns can't expect to hold a candle to traditional practitioners. There is, however, methodological progress to be made, both in paleography and (as shown by the Karlgrenian tradition) historical linguistics. Specifically, for example, the term 本義 is often used in a hand-wavy way, ambiguously interpretable as involving a claim about language or one about writing (or both). Sometimes this problem doesn't matter, but other times it is crucial.

Minhv said,

October 22, 2018 @ 7:16 pm

@Chris Button

The above digitisation procedures make sense from a utilitarian perspective – we need a unified standard of the texts for ease of use. If you were a common student or reader wanting to access Chinese literature, you really wouldn't want to have to type what is now considered a Japanese character like 賛 to search for the desired passages.

Victor Mair said,

October 22, 2018 @ 7:55 pm

In traditional Chinese language studies, another 本 ("original") that requires scrutiny is běnzì 本字 ("original character"), which is invoked when scholars are uncertain which character should be used to write a certain morpheme, especially in topolectal research.

http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=8922#comment-489501

See especially here:

http://pinyin.info/readings/mair/taiwanese.html

=====

Many old-fashioned scholars are of the opinion that they can solve the problem of sinographless vernacular morphemes by engaging in a search for what are known as běnzì 本字 ("original characters"). Their belief is premised on the notion that words lacking characters are actually old usages that have survived in the spoken language and that all one has to do to remedy the deficiency is assiduously comb early lexicons and rhyme books for characters that sound more or less right and mean approximately the same thing. Undoubtedly, such searches sometimes result in valid identifications, but in far too many cases the rare characters culled from such sources as Shuo wen jie zi [Explanations of Simple and Compound Graphs; 100 CE] and Guangyun [Expanded Rhymes; 1008] are self-fulfilling prophecies of the obsession with authentication from the national past. No matter how diligently one searches, it will be impossible to find benzi for such essential Cantonese words as nei1 / ne1 ("this") and m4 ("not") because they are not based on common Sinitic roots. A similar situation obtains for all of the other nonstandard regional vernacular and colloquial languages including Pekingese, Sichuanese, and Taiwanese.

=====

Chris Button said,

October 23, 2018 @ 10:13 pm

@Minhv

Encouragingly, Ctext does correctly make a distinction between 賛 in the Xiao Erya and 贊 in the Shuowen. However, I did contact the owner of Ctext who said that the site can't be relied upon for accuracy concerning variant forms since it is only as good as the source materials being used (btw the traditional/simplified issue is not a problem as one base is simply used there). Without any solid evidence about which came first (for which one can't really rely on a single attestation anyway given the similar time depth for both variants), my hunch is that any scholars putting 賛 first are doing so more due to its nice "folk etymology" than anything else.

Chris Button said,

October 23, 2018 @ 10:48 pm

@ Ash

While I find Boltz's many articles on that matter to be great contributions to scholarship, I personally don't buy his (& his teacher Boodberg's) "polyphonic" arguments at all. Sure there are some sporadic cases (even as far back as the oracle-bones), but these are random isolated incidences which played no formative role. I actually published a short monograph based on my MA thesis refuting polyphony which, aside from my OC reconstructions, I would still largely stand by.

Quire right! It's essentially just the base xiangxing as the phonetic bases and the xingsheng phonetic derivatives thereof. That's it – give or take the odd isolated quirk – and polyphony is not needed to account for any of it.

Schuessler's companion book to Karlgren's GSR has a good introduction and then lays the characters out with reconstructions (a slightly modified version of Baxter 1992) in much the same way. He conflates several of Karlgren's separate series which is great, although he could actually have taken it further as he still breaks up certain series which should also be merged.

Ash said,

October 23, 2018 @ 11:16 pm

@Chris Button:

Sorry, I didn't phrase my question very clearly. I meant specifically something in regards to ablaut, or basically, variation in the main vowel in the same xiesheng series or etymologically related word group (here, I mean words — not characters — that are etymologically related). I've read the front part of Schuessler's OC dictionary in the ABC series. Is what he says in his companion to the GSR any different from that?

Minhv said,

October 24, 2018 @ 12:24 am

@Chris Button

The references certainly did not consider only one attestation of the glyph when they declared that 賛 was the earliest attested form! 賛 seems to be the only shape attested in samples dating to the Qin Dynasty. In contrast, I haven't managed to find a single record of 贊 dating from that time period at all, which is very concerning if one is trying to state that 贊 was the earliest form. A huiyi construction may not be convincing, but that certainly doesn't automatically qualify the alternative Xingsheng choice, especially when there is no paleographic evidence to suggest that the Xingsheng shape came first. It is entirely possible that neither 賛 nor 贊 were the first shapes, but something ancestral to both.

I'm also very curious as to what you consider as "similar time depth" – to me, this doesn't seem to be a useful indicator of (the lack of) glyph change. Unlike spoken words, glyph forms don't change nearly as smoothly with time. Consider the frequent amount of active attempts to change the script whenever a new dynasty replaces an old one; I'm of the opinion that script change is heavily political in nature. Qin to (Western) Han experienced a complete dynastic change, so their similar distance from the current period does not mean that the different glyph forms found in those periods should have equal consideration as candidates for the original form.

Chris Button said,

October 24, 2018 @ 9:47 am

@ Ash

Oh ok. Well in terms of ablaut I think it's really only Pulleyblank's work on the ə/a nucleus which is scattered across multiple journal articles. For me, etymologically related words generally (but in reality it can become a little more complicated) should vary only in ə/a while xiesheng series can vary in palatalization and labialization of the nucleus also.

The problem with ə/a (and by extension "vowelessness") is that it is an uncomfortable proposition for most linguists. This is perhaps particularly the case for those without phonetics training who may favor distinct segments over what is in reality a complex interaction across a syllable since there is no clean break between an onset, a nucleus and a coda.

@Minhv

Sure, that's what I suggested as a possibility above.

As Wang Li and others have pointed out, there is an etymological relationship between 贊/賛 and 佐 so ultimately its ideal phonetic if everything in the Chinese script were etymologically logical would be 左. The notion of two figures assisting each other is tempting in this regard, but until someone can demonstrate that 賛 must have preceded 贊 (all the evidence we have right now is too late to justify a "huiyi" analysis at our present state of knowledge) then I'm going with 先 (via 兟) as phonetic in 贊 and it's hardly like I'm going out on a limb there as the only person claiming that.

Chris Button said,

October 24, 2018 @ 10:27 am

Having said that, as I mentioned above, the fact that there are two 兟 rather than one 先 does favor the later "phoneticisation" that you mentioned which is all the more so given that digraphs/trigraphs are not usually phonologically related to their unitary predecessors (compare 木 and 林 for example, although 林 and 森 are related). However, against that is also the fact that the earlier pronunciations of 先 and 贊 would have diverged quite a lot by that stage. Incidentally, Shirakawa Shizuka talks a little about the possible graphic, and also semantic, influence of 兓 and associated words. It's a shame we can't go anywhere phonetically with 兓 since it has a bilabial *-m coda, and the the only evidence for sporadic (dilaectal?) bilabial dissimilation in the oracle-bones is expectedly after bilabial onsets (as btw one can also see in Cantonese or some Min languages today) in cases like 般 *pán whose phonetic is originally 凡 *bàm.