"Whose speech is free of p3's"

« previous post | next post »

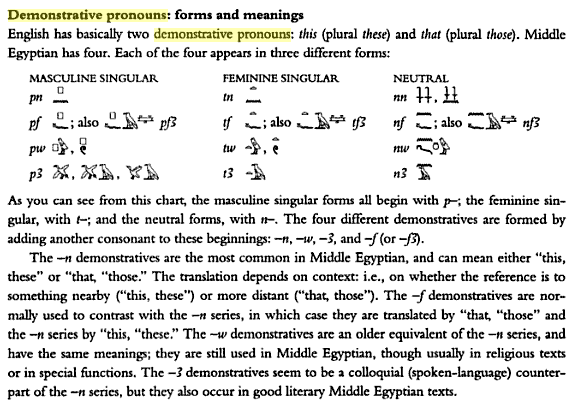

In response to "Strunk and Ptah", 10/6/2011, Reader KD has pointed me to a passage in James P. Allen, "Middle Egyptian: an introduction to the language and culture of hieroglyphs", 2000, which describes a real instance of ancient Egyptian prescriptivism. Crucial background is provided by the history of demonstratives in Egyptian:

This change-in-progress was apparently stigmatized, with the expected sociolinguistic consequences:

This appears to be a reference to the Stela of Mentuwoser, dated to 1945 B.C., displayed physically in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Gallery 100, and displayed virtually here. The relevant part of the translation, attributed to the same James Allen, is given as:

This appears to be a reference to the Stela of Mentuwoser, dated to 1945 B.C., displayed physically in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Gallery 100, and displayed virtually here. The relevant part of the translation, attributed to the same James Allen, is given as:

I am generous with surplus [9] of food: there is no lack for one to whom I give. I share the greater portion of meat with those who sit [10] next to me. I am one beloved of his kindred, to whom his family is attached. I have not hid my face from the one who is in [11] servitude. I am a father to the orphan, a helper of widows. No man has gone to sleep hungry [12] in my domain; I have hindered no man from the ferry; I have cut down no man less powerful than I; I have tolerated no [13] slanderer. I am one who talks according to the style of officials, free of outmoded speech. I am a proper judge, [14] who shows no partiality to the one who can give rewards.

However, there's something about the museum-site's translation that seems odd to me. Prof. Allen's explanation in Middle Egyptian is that "the -3 demonstratives seem to be a colloquial (spoken language) counterpart of the -n series", which eventually turned into a definite article, and "at one time […] was considered a mark of lower-class or 'street' language". But the translation of Mentuwoser's Stela boasts that he "talks according to the style of officials, free of outmoded speech" — whereas being "free of p3's" would apparently have been the opposite of "free of outmoded speech", and more like "free of innovative colloquialisms".

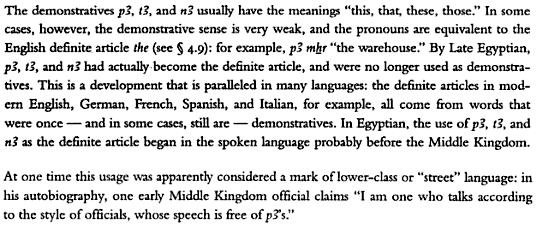

This does seem to be the right autobiograpical stela — KD indicates this passage as the crucial one, noting that it ends with with a pintail duck landing (Unicode 13170 EGYPTIAN HIEROGLYPH G041) followed by followed by an Egyptian vulture in profile (Unicode 13140 EGYPTIAN HIEROGLYPH G001), representing p3, and then the quail chick (Unicode 13172 EGYPTIAN HIEROGLYPH G043), which is the sign for 'w', here marking the plural:

Details aside, I find it interesting that Mentuwoser (or rather his son, speaking for him) gives his linguistic purity in the middle of a list of evidences of his charity, empathy, and honesty, and not (for example) in the proofs of political loyalty and diligence:

[5] I am a diligent subordinate in the king's house, who is sent on missions because of decisive character. I have acted as granary overseer during the counting of [6] barley; I have acted as overseer of more than 3,000 people; I have acted as overseer of cattle, overseer of [7] goats, overseer of donkeys, overseer of sheep, overseer of pigs; I have directed clothing to the treasury; [8] account has been taken by me in the king's house, and I have been acclaimed and thanked.

Or in the list of proofs of wealth:

I am wealthy, well supplied with fine things: there is nothing I am missing in all my things. [15] I am an owner of cattle, with many goats, an owner of donkeys, with many sheep. I am rich in barley and emmer wheat, fine [16] in clothing: there is nothing missing from all my wealth. I am well supplied with boats and rich with vintage.

Update — KD sends in a note from a friend doing a doctorate on the Egyptian language, who clarifies the analysis that (presumably) lies behind the two apparently different translations:

This blog is really interesting. The text and what it appears to say is really interesting too, as its one of the few cases I know of where Egyptians seem to talk about their own language. The transliteration and translation can be a bit variable for this text, particularly the translation of pA. In the first translation by Allen it is taken to be the definite article. This is seen to be low speech I think because pA is used as a demonstrative in Middle Egyptian but in Late Egyptian 'low' dialect it is the definite article 'the'. In the second translation it seems to be taken as the verb pAw, a conjugated form of pAi 'to have done in the past', which seems to me to be more likely. The problem with this is this word is never determined with the 'speech' determinative. The online worterbuch even has a word pAw (?) written this way as 'anything unseemly'; perhaps the meaning of the word then is old or anachronistic speech. Although the scribe could be merely amending the word pA 'the' by putting the speech determinative after it to indicate the spoken word.

I would have it as:

ink mdw r r-a sr.w Sw.y m Dd pAw/pA.w

I am one who speaks according to the state/presence/style of the officials, empty/free of saying that which was in the past.

The alternative if pAw is the article/demonstrative would be, 'free/empty of saying pAs'

The other reason why I would err to the side of the verb pAw as opposed to 'the' is that in this stele the scribe seems to more regularly use the plural strokes than the quail chick to pluralize words. Although I can see one or two exceptions to this in the stele. However, the idea of not speaking like the past doesn't really seem to fit with Egyptian cultural precepts, where the past is usually seen as something to be emulated rather than shunned, unless the speaker is referring to the immediate chaotic past of the First Intermediate Period.

It's really interesting stuff and not altogether clear what way to take pA. It'd be nice if there were some more examples of it. This period apparently has the first attestations of some late egyptian-isms in some letters etc so it would make historical sense if the official was saying I don't use the 'low' pA-speech.

David Eddyshaw said,

October 15, 2011 @ 8:47 am

Pure guesswork – but perhaps the Egyptians of this period in fact believed that lower-class speech was in fact archaic, as not having progressed to the sophistication of official speech.

I don't expect they had anything llike our understanding of language change. (I seem to remember reading that even Dante did not understand that his own speech was actually descended from Latin, but supposed that ther had always been a diglossic relationship between the two.) We know that the p3-series is innovative, but Mentuwoser may well not have done. If he was aware that these forms were absent from older records, perhaps he would have interpreted this as a matter of register rather than age.

[(myl) It's certainly plausible — though I know nothing about it — that the ancient Egyptians applied the "newer is better" principle to speech and text as well as other areas of culture. After all, that's the basis on which Dryden attacked stranded prepositions:

… these absurdities, which those poets committed, may more properly be called the age's fault than theirs. For, besides the want of education and learning, (which was their particular unhappiness,) they wanted the benefit of converse […] Their audiences knew no better; and therefore were satisfied with what they brought. Those who call theirs the Golden Age of Poetry, have only this reason for it, that they were then content with acorns, before they knew the use of bread …

But the translated passage itself refers (I think) only to p3's, without specifying whether they're archaic or innovative; so to use the translation "outmoded expressions", Allen must be relying on some other knowledge of the kind that you suggest. Whatever the explanation, I'd like to learn more.]

Jerry Friedman said,

October 15, 2011 @ 10:19 am

Does anyone know whether he really avoided p3's, or just avoided using them with the non-standard meaning of his time? The extracts seem to be short on demonstratives, so if his writing is unknown elsewhere, I suppose there might be no way to tell.

It's probably too much to hope for that there would be a non-standard p3 on the stele.

Rubrick said,

October 15, 2011 @ 10:59 am

An Occamian explanation: perhaps "outmoded" does not mean what Mr. Allen thinks it means? I've certainly had commoner words misdefined in my brain.

On an unrelated note, "I am an owner of cattle, with many goats, an owner of donkeys, with many sheep" could easily lead someone naive of animal husbandry rather badly astray…

Henning Makholm said,

October 15, 2011 @ 11:50 am

"Whose speech is free of p3's" sounds like a more literal translation than "free of outmoded speech", so I would expect "outmoded" to be the second translator's interpretation of why not having p3's would be a good thing.

I don't think it should surprise us that someone would consider his linguistic conservatism primarily a moral virtue rather than a political or economic one. This guy wasn't dropping his p3's for the king's sake or because it would making him rich; he did it because it's the right thing to do just like feeding the poor and upkeeping justice.

[(myl) This is certainly not surprising — Horace and Quintilian used the metaphor of moral lapses in describing deviations from linguistic norms, as described here, and so have many others in the succeeding centuries. But I was interested to find an implicit endorsement of this metaphor in a source from 1945 B.C.]

Finally, I find the "demonstrative pronoun turns into definite article" feature fascinating. I knew this had happened in Romance languages and can infer that Germanic languages must have gone through something similar (since PIE had no definite articles). If the same thing happened in Egyptian thousands of years earlier, that hints that it might be a universal tendency. But if that is so, where do the original languages without a definitene-indefinite distinction come from? Are there examples of languages that have lost definiteness over time?

Tom V said,

October 15, 2011 @ 12:07 pm

Very tangentially related: In Astérix et Cléopatre the scribe recites a "spelling rule" for hieroglyphs, similar to the traditional English "i before e except after c…." I'm not certain how strong the historical evidence for this rule is, and in any case the scribe appears to be less than thoroughly competent.

LDavidH said,

October 15, 2011 @ 12:19 pm

@Henning Makholm: Yes, I have come across people who act as if using "bad grammar" (in their case, in particular singular "them") was somehow immoral, not just mistaken. So grammar can definitely be seen as a moral issue!

And I second your second question: are there languages that have lost the definite/indefinite distinction?

GeorgeW said,

October 15, 2011 @ 3:04 pm

Could there be a urban (innovative, sophisticated) vs rural (conservative rube) factor expressed here?

ella said,

October 15, 2011 @ 4:22 pm

Does anyone know what phone "3" represents?

Carl said,

October 15, 2011 @ 5:04 pm

"I am wealthy, well supplied with fine things:"

Whoa, we figured out who Kanye West was in a past life!

Korshi said,

October 15, 2011 @ 5:12 pm

@ella

No-one knows exactly what Egyptian sounded like, since like classical Hebrew vowels were never marked, the whole language has been reconstructed from texts and there was a lot of phonetic change over the 4000 years it was a spoken language.

Having said that, Allen (Middle Egyptian p.15) says the original promunciation of '3' was probably l or r, but by the Middle Kingdom it had become 'y' or the glottal stop (aleph). Most Egyptologists just pronounce it 'pa'. It was probably pronounced differently depending on the word it preceded, since in Coptic (whose phonology is much clearer) articles are proclitic, and the descendent of 'p3' is 'p' (written with the Greek 'pi'), or 'pe' (pi epsilon) before double consonants. There's a good discussion of Egyptian phonology at the bottom of this page http://www.friesian.com/egypt.htm

David Donnell said,

October 15, 2011 @ 8:19 pm

Sorry I'm still trying to process and heed the aforementioned "Never end a sentence with a [bird symbol]" rule.

maidhc said,

October 15, 2011 @ 11:11 pm

The Sydney Morning Herald published the following comment on the original cartoon (October 8, 2011):

Matt_M said,

October 16, 2011 @ 2:20 am

@Henning Makholm & LDavidH:

"Are there examples of languages that have lost definiteness over time?"

Aramaic seems to be one: (quoting from Wikipedia)

The emphatic or determined state [which contrasts with the construct and absolute states] is an extended form of the noun that functions a bit like a definite article (which Aramaic lacks; for example, kṯāḇtâ, 'the handwriting'). It is marked with a suffix. Although its original grammatical function seems to have been to mark definiteness, it is used already in Imperial Aramaic to mark all important nouns, even if they should be considered technically indefinite. This practice developed to the extent that the absolute state became extraordinarily rare in later varieties of Aramaic. [i.e., no distinction was made on nouns between definite or indefinite; in adjectives, the absolute/emphatic distinction denoted a distinction between adnominal and predicative uses].

I'd be surprised if there weren't other examples out there.

Ran Ari-Gur said,

October 16, 2011 @ 8:35 am

@Henning Makholm and LDavidH: Apparently Old Georgian used its distal demonstratives (like English "that") as definite articles, taking the same path as many other languages, but then stopped and backtracked: in today's Georgian, the reflexes of those demonstratives occur only as demonstratives, not as mere definiteness markers. [PDF link]

gido said,

October 17, 2011 @ 4:12 am

Starting from the rectangular sign just above the damage:

šwy m ḏd(=i) pȝ.w

lacking in speech-my (are) p3.PLURAL

"P3s" are absent in my speech.

(The square sign above the landing duck is p and also belongs to the word: p p3 3 w = p3.w.)

Rohan F said,

October 18, 2011 @ 12:23 am

@Matt_M, Abkhaz also uses the "definite" article (prefixed /a-/) on most otherwise unmarked nouns. Often it's referred to as a "definite-generic" article for this reason. This contrasts with its sister-language Abaza, which has the prefix a- serving in a more restricted definite function.

gido said,

October 18, 2011 @ 1:57 am

Sorry, I got the šwy m idiom wrong. Second attempt:

šwy m ḏd pȝ.w

being-free of speaking p3s

xyzzyva said,

October 25, 2011 @ 6:52 am

Regarding demonstrative–>article, I have seen it suggested that Mandarin's proximal demonstrative 这 zhè is in the early stages of a move to an article.

Not really sure how you'd define a transition point between the two, though. And perhaps it would be interesting to know if any definite articles come from somewhere other than a demonstrative. Perhaps the Norse suffixes -en, etc.? Or Arabic -ال (which operates arguably as an inflection instead of an article, anyway)?

Matt_M said,

October 26, 2011 @ 3:42 am

@ xyzzyva:

Regarding the -en/-et suffixes in Scandinavian languages: yes, they did apparently develop from a post-posed demonstrative, namely (h)inn/(h)it: compare Old Icelandic hinn ulfr (that wolf, the wolf), ulfrinn (the wolf), presumably from ulfr (h)inn, (that wolf, the wolf) – the word order [noun demonstrative] was normal in the pre-mediaeval Norse attested in runic inscriptions.

I think something similar happened in the South-Eastern European languages like Romanian and Bulgarian that have suffixed definite articles.

Regarding Arabic (and Hebrew): the following article notes that the definite prefix in Hebrew and Arabic has been usually assumed to have derived from a demonstrative, but argues for another analysis – that the ancestor of the article was an adjective prefix denoting a non-predicative function (a kind of anti-copula, if you like):

Pat-El, N, 2009, 'The Development of the Definite Article in Semitic: A Syntactic Approach', Journal of Semitic Studies 54:1

(available at academia.edu, if you don't mind registering)