Toxic clams

« previous post | next post »

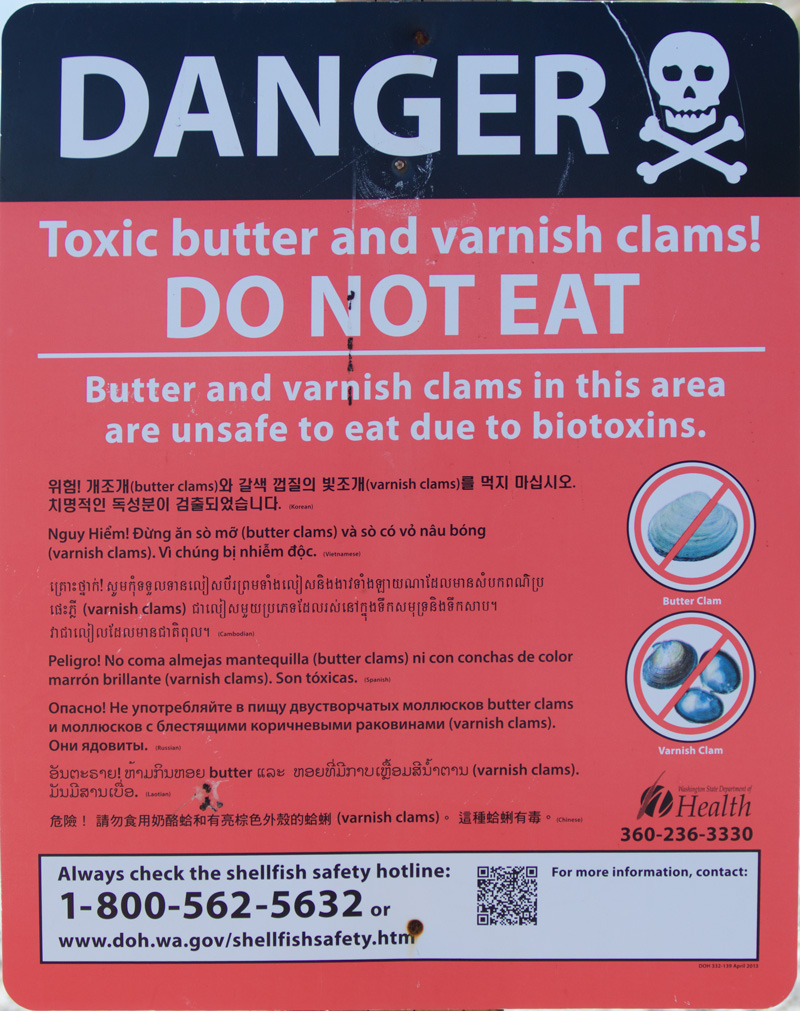

Photograph of a sign at Sequim Bay, Washington taken by Stephen Hart:

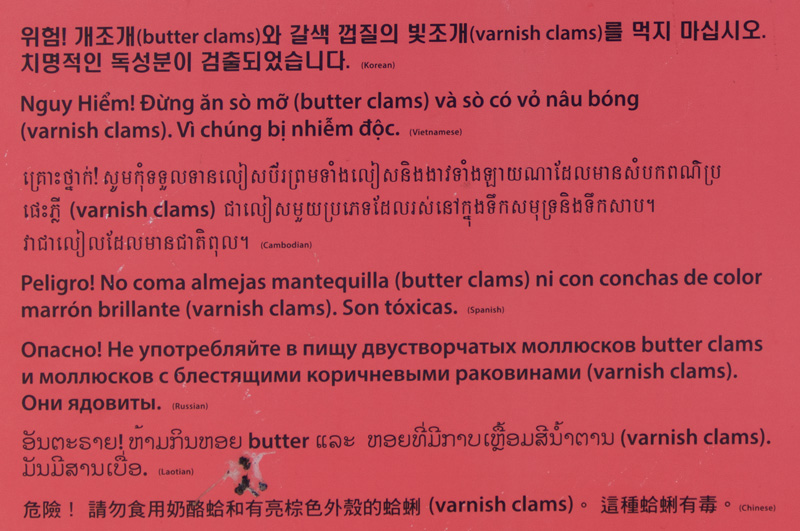

These are the same languages (Korean, Vietnamese, Cambodian, Spanish, Russian, Laotian, and Chinese) as on the sign discussed in this post:

"Toxic shellfish warning in seven foreign languages " (9/16/16)

A big difference here, though, is that English designations ("butter clams" and "varnish clams") are parenthetically added to the translations into each of these languages. This is undoubtedly due to the fact that the precise names for these particular clams may not be known, and indeed may not exist, in these languages. The names are unusual enough in English that I suspect most non-locals would do a double-take upon seeing them ("butter clam" is perhaps slightly better known outside of the immediate area than "varnish clam").

Unlike the treatment of the languages in the previous post, I will only explicate the Chinese warning this time. If Language Log readers would like to explain various features of the other languages, they are welcome to do so, but please always provide Romanized transcriptions and translations.

Wéixiǎn! Qǐng wù shíyòng nǎilào gé hé yǒu liàng zōngsè wàiké de gélí (varnish clams). Zhè zhǒng gélí yǒudú.

危險! 請勿食用奶酪蛤和有亮棕色外殼的蛤蜊(varnish clams)。這種蛤蜊有毒。

Danger! Do not eat cheese clams and clams with shiny brown outer shells (varnish clams). They are toxic.

Notes

1.

I have always called butter "huángyóu 黄油" (lit., "yellow oil / grease / fat") in Chinese and most people I know also call it that, but about half as many refer to butter as "niúyóu 牛油" (lit., "cow oil / grease / fat").

When young, butter clams look rather like a pat of butter, but as they grow bigger and older they turn to a gray-white color.

The scientific name of this clam is Saxidomus gigantea.

The second syllable of gélí 蛤蜊 ("clam") was omitted in the translation on this sign. Normally these two characters are considered to be bound to each other in this term. The first character can also be pronounced as há, in which case it enters into the word for "frog; toad". See:

"Of toads, modernization, and simplified characters " (8/16/13)

The second syllable of gélí 蛤蜊 ("clam") is sometimes confusingly written with a much more complicated character, lì 蠣 (simpl. 蛎), that means "oyster", which is also called by various other names.

In contrast with the occurrence of the English after the names of the clams in most of the other instances on this sign, it was omitted here, perhaps because the translator knew that their nǎilào 酪蛤 means "cheese", not "butter".

2.

Varnish clams are also called "purple varnish clams", "mahogany clams", and "dark mahogany clams". The scientific designation for this type of clam is Nuttalia obscurata. It is an invasive species, originally from Asia (it is native to Japan), that initially appeared on British Columbia beaches in the early 1990s, and from there rapidly spread to beaches in Washington State.

The Chinese word for "varnish" is qī 漆.

Bathrobe said,

May 29, 2017 @ 12:14 am

The Internet has three Chinese names for the butter clam. Taiwanese sites give 阿拉斯加粗紋蛤 Ālāsījiā cū-wén há 'Alaskan coarse pattern clam'. Mainland sites give 大石房蛤 dàshí fáng há 'large stone-chamber clam' and 阿拉斯加石房蛤 Ālāsījiā shí fáng há 'Alaskan stone chamber clam'. Some Mainland sites give 黄油蛤蜊 huángyóu gélí 'butter clam'.

The name 石房蛤 shí fáng há 'stone chamber clam' is from the local Chinese member of the genus, which is scientifically known as Saxidomus purpuratus (紫石房蛤 zǐ shí fáng há 'purple stone chamber clam').

I'm always curious why translators feel impelled to make up or literally translate names when reasonably close or accurate scientific names can be found on the Internet. It would surely not have been too hard to translate it as "大石房蛤 (butter clam)", which covers all bases. 食用奶酪蛤 'edible cheese clam' is just sloppy.

The Internet is less satisfactory for Nuttallia obscurata. The species has been known by the scientific names Soletellina obscurata, Nuttallia solida, Psammobia olivacea, Sanguinolaria olivacea, and Soletellina obscurata.

The Japanese name is ワスレイソシジミ wasure iso-shijimi 'forgotten? rock clam' (忘磯蜆). It is almost indistinguishable from the イソシジミ iso shimiji or Nuttallia olivacea, which is known in Chinese as 橄榄血蛤 gǎnlǎn xuě-há 'olive blood-clam' or 紫彩血蛤 zǐ-cǎi xuě-há 'purple blood-clam'.

"血蛤 (varnish clam)" would surely have been ok for the sign.

B.Ma said,

May 29, 2017 @ 2:29 am

Bathrobe, you seem to have parsed 食用 as part of "edible cheese clam" instead of part of "please do not eat".

Except for the first words of the Korean and Vietnamese (both derived from the Chinese 危險), the only other language I can somewhat understand is the Spanish – where it looks like "butter clam" has also been translated directly but "varnish clam" has, like the Chinese, been described as "clam with bright brown shell". For some reason, the parenthetical butter clam has been omitted from the Chinese.

It looks as if the authors sent off a completely different English sentence from what is on the sign to be translated. I await further comments from speakers of the other languages.

If I were designing the sign, I would have just used the English names of the clams in all languages, and directed readers to look at the pictures.

On further thought, this may be a Pullum-nerdview example too. Why bother specifying the types of clams at all? Are there other types of clams which are safe to eat? Even if only some clams are toxic, is it wise to trust the general public to tell the difference based on a sign with poor photos that is going to be subject to weathering? Why not just say do not eat any creatures with shells?

Philip Taylor said,

May 29, 2017 @ 3:00 am

What surprised me most, given the location of the sign, is the apparent absence of any warning in any of the indigenous Native American languages …

Bathrobe said,

May 29, 2017 @ 4:05 am

@B.Ma

I did, too. My bad!

Bathrobe said,

May 29, 2017 @ 5:40 am

According to this site, "Saxitoxin is a paralytic poison from Alaska butter clams (Saxidomus giganteus), toxic mussels (Mytilus californianus), the plankton Gonyaulax cantenella and Protogonyaulax tamarensis". So it does appear to be particularly associated with certain species.

The English name of the toxin is derived from Saxidomus, the genus to which the butter clam belongs. The Chinese name for saxitoxin is 石房蛤毒素 shífáng-há dúsù 'Saxidoma toxin', also based on the name of the genus.

The reason I feel that using the correct Chinese names (石房蛤, 血蛤) is important is that 1) it is better to be accurate than slipshod and 2) there may be Chinese speakers who are familiar with those shellfish, especially 石房蛤, from a Chinese environment.

It's occurred to me that local Chinese might actually be familiar with the butter clam as 奶酪蛤, but the only source for 奶酪蛤 on the Internet is a couple of Taiwanese dictionaries, one of which has the note that it is 石房蛤屬大型食用蛤,產於北美洲太平洋沿岸. Perhaps the translator was relying on this source.

At any rate, with the names of plants and animals I think it's always better to use an accepted term than just translating on the fly. For instance, surely it's better to translate 'swan goose' (the bird) as 鸿雁 hóng-yàn, by which it is known in China, than simply coming up with a nonce translation like 天鹅雁 tiān'é yàn 'swam goose', which isn't used in Chinese.

Victor Mair said,

May 29, 2017 @ 7:26 am

As I pointed out in the o.p., 蛤 is pronounced gé when it means "clam" and há when it enters into words meaning "frog; toad".

Bathrobe said,

May 29, 2017 @ 7:41 am

I stand corrected. All those há should be gé.

Anonymous Coward said,

May 29, 2017 @ 8:39 am

Philip Taylor: If you're so local as to be able to speak a local language, the theory would be that your ethnobiological knowledge would be much more than this.

FM said,

May 29, 2017 @ 8:58 am

The Russian follows a similar pattern (the italics are untranslated English):

"Do not eat (literally: use for food) the bivalve mollusks butter clams or mollusks with shiny brown shells (varnish clams). They are poisonous."

I don't think there's a good generic word for "clam" in Russian. It's unclear how useful the particulars of the sign would be to a monolingual Russian speaker but I guess they didn't want to just go with "don't eat the bivalves" and have people guessing at what the longer English message is.

Victor Mair said,

May 29, 2017 @ 9:40 am

Excellent reply, Anonymous Coward!

When I was doing the research for the o.p., I noticed that the English Wikipedia article on Saxidomus gigantea ("butter clam") linked to articles in the following languages: Cebuano, Nederlands, Svenska, and Winaray. The English article on Nuttallia obscurata ("varnish clam") had links to articles in the same four languages.

I was intrigued by the interest of speakers of these four languages in these particular Pacific Northwest clams. Well, Cebuano, an important regional language of the Philippines was not so surprising to me, but I wondered why Scandinavian speakers would be concerned enough about these clams to write Wikipedia articles about them, unless it were purely for the sake of scientific completeness.

The language that really captured my attention was Winaray, because I'd never heard of it. When I looked it up and discovered that it too is a regional language of the Philippines, then it made sense to me that Winaray (also called Waray [an exonym meaning "none" or "nothing"] or Waray-Waray) speakers, many of whom live in the Pacific Northwest and dig for these clams, would care enough about them to compose the relevant Wikipedia articles.

Stephen Hart said,

May 29, 2017 @ 11:05 am

Philip Taylor said, "What surprised me most, given the location of the sign, is the apparent absence of any warning in any of the indigenous Native American languages …"

Interesting point. Port Angeles has many signs with at least a greeting in Klallam. Olympic National Park just added a new sign to the Hurricane Ridge entrance with a welcome greeting— ʔənʔá č’ə́yəxʷ —in Klallam.

http://www.seattletimes.com/life/outdoors/new-olympic-national-park-sign-welcomes-in-language-you-might-not-recognize/

The signs are from the Washington State Department of Health, so are statewide. Adding indigenous languages to state warning signs would be a task:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Indigenous_languages_of_Washington_(state)

Anonymous Coward said, "Philip Taylor: If you’re so local as to be able to speak a local language, the theory would be that your ethnobiological knowledge would be much more than this."

These are usually seasonal warnings, based on samples of biotoxins, so general ethnobiological knowledge about particular species wouldn’t help.

B.Ma said, Are there other types of clams which are safe to eat?

Yes. According to the Washington State Department of Health PDF on clams, Butter Clams and Varnish Clams retain toxins such as paralytic shellfish poison longer than other species.

http://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/4400/332-087-Shellfish-ID.pdf

Alyssa said,

May 29, 2017 @ 11:11 am

Being completely unfamiliar with these varieties of clam, "Toxic butter and varnish clams!" was hilariously nonsensical the first time I read it. It sounds like I'm being warned that butter is toxic and then told to varnish some clams.

Once I'd sorted out the real meaning, I had the same question B.Ma did: Why not just say "clams"? Are there non-toxic clams in this area?

GeorgeW said,

May 29, 2017 @ 1:47 pm

It seems to me that butter and varnish would be a toxic mix even in the most benign of creatures.

Christian Weisgerber said,

May 29, 2017 @ 3:30 pm

@Victor Mair

Cebuano, Nederlands, Svenska, and Winaray are those Wikipedia language editions where automated programs create stub articles for as many biological species as they can find. I don't know what database they are drawn from, but this is indeed just for the sake of completeness.

CuConnacht said,

May 29, 2017 @ 6:45 pm

Are there many people literate in a local Native American language who could not read the English? Any?

tangent said,

May 30, 2017 @ 1:19 am

Yes, there are other relevant clam species, a good half a dozen of them — Manila, littleneck, horse, razor, and others. Not even getting into geoduck. Butter and varnish clams are a minority of the species. It's quite common for closures to be specific to butter and varnish clams, as Stephen Hart described. The current map:

https://fortress.wa.gov/doh/eh/maps/biotoxin/biotoxin.html

ajay said,

May 30, 2017 @ 3:59 am

"Are there many people literate in a local Native American language who could not read the English"

Yes, exactly. Putting up signs in national parks that say WELCOME in the local NA language(s) as well as English isn't about ensuring that everyone who walks through the gate knows they are welcome. It's about recognising that there are more cultures in the area than just the English-speaking one. Warning signs serve a different purpose, and I'd speculate that the set of non-English languages chosen for this sign fall at the intersection of [people speaking this language live in this area], [people speaking this language may well not read English fluently] and [people speaking this language like gathering clams].

"Being completely unfamiliar with these varieties of clam, “Toxic butter and varnish clams!” was hilariously nonsensical the first time I read it."

Me too. I was expecting some sort of bizarre menu translation.

Adam F said,

May 31, 2017 @ 4:35 am

Some years, I was having dinner with Finnish, Swedish, & British colleagues in a restaurant in Finland. The menu was trilingual (Finnish, Swedish, & English), and I saw an interesting dish in the English section although I had no idea what the main ingredient was. (Unfortunately I can no longer remember the word.) I asked one of the locals what X meant, & he (meaning to be helpful) told me there was an English section with everything.

I said, "I am looking at the English menu!" It turned out to refer to something similar to a trout but found only in a specific area of Finland. The English word was suspiciously almost exactly the same as the Swedish one (of course the Finnish was different), and I think there might not really be an English name for it. (I recall that that it was delicious.)

Maybe menus should list all the ingredients by genus & species … well, maybe that's not enough detail for Capsicum annuum!