A child's substitution of Pinyin (Romanization) for characters, part 2

« previous post | next post »

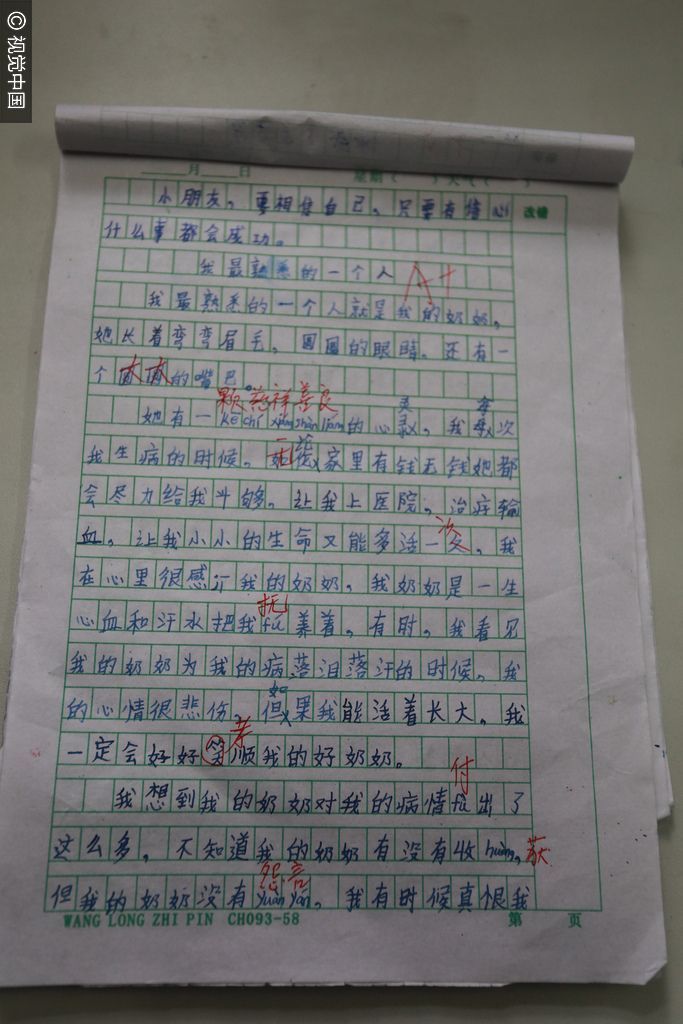

This is a photograph of a page from an essay written by a third grade student at an elementary school in Suining, Sichuan Province, China:

The title of the essay is "Wǒ zuì shúxī de yīgè rén 我最熟悉的一个人" ("The person with whom I am most familiar"). It's about the little girl's grandmother who raised her after her parents were divorced. The little girl, who is now nine years old, suffers from zàishēng zhàng'ài xìng pínxiě 再生障碍性贫血 ("aplastic anemia"). This is a rare and very serious disease involving the insufficient production of new blood cells whose treatment may require immunosuppressive drugs and other medications, blood transfusions, a stem cell transplant, bone marrow donation, and so forth. Even with the best treatment, the survival rate is not high.

The little girl's essay includes these words:

Wǒ kànjiàn wǒ de nǎinai wèi wǒ de bìng luò lèi de shíhòu, wǒ de xīnqíng hěn bēishāng. Rúguǒ wǒ néng huózhe zhǎngdà, wǒ yīdìng huì hǎohǎo xiàoshùn wǒ de hǎo nǎinai.……

我看见我的奶奶为我的病落泪的时候,我的心情很悲伤。

When I see my grandmother crying about my illness, my heart is very sad. If I can stay alive and grow up, I will certainly take care to be filial to my dear grandmother….

When the little girl's essay, especially these words, were circulated on WeChat, it swiftly went viral, and that is how I found out about it. For an article in Chinese that describes how the little girl came to write this essay and what happened after her teacher read it, see here.

What particularly caught my attention about the essay is how the little girl used Pinyin to write terms she didn't know in characters. Here are those which I spotted in the photograph above:

kē cíxiáng shànliáng 颗慈祥善良 (m.w. [measure word] for heart "kind, honest"); cí is misspelled as chí

fú 抚 ("foster; nurture"); fú has the wrong tone for fǔ, unless she's writing out the sandhi

fù 付 ("expend; commit")

huò 获 ("obtain; reap"); the final part of the Pinyin is not clear

yuànyán 怨言 ("complaints")

In one place, she substitutes the homophonic character xiào 笑 ("laugh") for 孝 ("filial").

The substitution of Pinyin for characters that one is unable to recall or never learned, both for children and for adults, is a widespread and growing phenomenon. We've encountered it many times before on Language Log. Here are a few relevant posts:

- "A child's substitution of Pinyin (Romanization) for characters" (11/9/14), with links to other posts

- "Character amnesia and the emergence of digraphia" (9/25/13)

- "Substituting Pinyin for unknown Chinese characters" (12/3/13)

And this classic:

- "Dumpling ingredients and character amnesia" (10/18/14)

All citizens of China who have received any education at all are familiar with Pinyin, because that is how every child in the PRC who goes to school begins the process of learning to read and write. The use of Pinyin is reinforced in many other ways, including dictionary lookup, indices, technical terms, advertising, etc., but most of all for inputting text in electronic devices, the vast majority of which is done via Pinyin. The government is neither promoting nor prohibiting the use of Pinyin beyond the initial stages of learning how to read and write. It is just happening. That is why I always speak of digraphia in China as "emerging". When it reaches a certain stage, we will look around and see that it has become de facto digraphia and that Pinyin will be functioning as kana does for Japanese.

[h.t. Geok Hoon (Janet) Williams; thanks to Fangyi Cheng, Yixue Yang, and Jing Wen]

JS said,

October 14, 2016 @ 9:06 pm

Incredible.

Re: language, also 斗够… dou4(?) = 凑[钱]? New to me.

Also ji1 激 is in pinyin.

Dai Huteng said,

October 14, 2016 @ 9:11 pm

The power of Chinese character is too large to be replaced by pinyin, while Latin alphabets(or Roman alphabet) does enter into Chinese character's system with the English words, for example, "word 天"(我的天–My Godness)–someone prefer "word 哥"(我的哥–literally, My Brother).

Dai Huteng said,

October 14, 2016 @ 9:47 pm

斗够 is 个够 exactly

JS said,

October 14, 2016 @ 10:15 pm

Nope, apparently it is 四川话。Reading down though it seems it is incorrect to equate 斗 with 凑. They mention expressions like 斗账 (=对帐). Also here it says that 鬥錢 means 集資湊錢 in 南昌 Gan

Victor Mair said,

October 14, 2016 @ 10:27 pm

@JS

I didn't catch the ji1 激 because the teacher didn't correct it.

Thanks for that and for the notes on Sichuanese. I suspect that other aspects of the little girl's writing (different tones, different romanization [i.e., pronunciation]) may also be due to Sichuanese influence.

Victor Mair said,

October 14, 2016 @ 11:40 pm

From a graduate student:

As a native speaker of Sichuanese topolect, I can tell that dou (may be the word 斗) is a very particular usage in the region, which means pooling money to a certain amount that is beyond one's normal capacity. In spoken Sichuanese, it is close to the third tone, dǒu. My mom always says that topolects are far more expressive and lively than Mandarin, and I think so too.

Jill Baird said,

October 15, 2016 @ 2:20 am

How sad if Chinese characters eventually disappear. There is a richness of history and allusion in them that pinyin can never replace. When I studied in China in the seventies, I was taught that the long term plan (after puji putonghua) was to use only pinyin. I hope that policy has been dropped.

Victor Mair said,

October 15, 2016 @ 6:45 am

@Jill Baird

"How sad if Chinese characters eventually disappear."

Maybe in two or three thousand years. No, essentially never.

Has Egyptian disappeared? Has ancient Greek disappeared? Has Sanskrit disappeared? Think of how much serious, honest effort people expend on keeping these languages alive.

And what about during the coming centuries? For that, please read the last paragraph of this post and take a look at the links preceding it. Digraphia does not mean the eradication of characters.

Brett said,

October 15, 2016 @ 7:46 am

@Victor Mair: While I don't think Chinese characters are ever going to suffer the same fate, the first alphabet for writing Greek and the first two ways of writing Egyptian were all lost to understanding for at least a millennium. While at least one tongue descended from ancient Greek remains a vibrant native language, Coptic Egyptian has fewer than a thousand fluent speakers and been almost exclusively a liturgical language for centuries.

Wang Yujiang said,

October 15, 2016 @ 8:57 am

@Jill Baird

Don’t worry about Chinese characters disappearing. It won’t happen. However, Chinese people will use pinyin soon and eventually put Chinese characters into the history museum. The reason is that Chinese characters are less efficient than alphabets as a tool.

The Other Mark P said,

October 15, 2016 @ 4:49 pm

How sad if Chinese characters eventually disappear. There is a richness of history and allusion in them that pinyin can never replace.

I don't think romantic notions of "history and allusion" is sufficient reason to hold back a culture of a billion people.

Anyway, history and allusion aren't character dependent. Unless you mean the trivial history of the characters themselves (most of which is totally unknown to most Chinese.)

The only thing actually lost will be calligraphic art. But I'm not for returning to hand-written books in the West based on that, and I doubt you are either.

Andreas Johansson said,

October 16, 2016 @ 3:45 am

The other thing that would be lost is popular access to everything that doesn't get transcribed into pinyin. Given the size of the market, surely everything important will be, for some reasonably inclusive definition of important, but not everything.

cliff arroyo said,

October 16, 2016 @ 9:35 am

"The only thing actually lost will be calligraphic art."

It hasn't been lost in Vietnam…

http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-DxVeRqjErGE/UvfwD7JBh2I/AAAAAAAADt0/_VSCZT3ATic/s1600/Hien+Hoc.jpg

David Marjanović said,

October 16, 2016 @ 10:26 pm

This looks really compelling!

Eidolon said,

October 17, 2016 @ 3:59 pm

"When it reaches a certain stage, we will look around and see that it has become de facto digraphia and that Pinyin will be functioning as kana does for Japanese."

But kana emerged not only as a learning tool, but due to the need to express native Japanese words, particles, and foreign loan words for which there was no accepted kanji. Pinyin by contrast is taught only as a stage in the process of obtaining character literacy. The goal of pinyin education in the PRC is character literacy, and as such for any word written in pinyin, there is an equivalent word written in characters, which literate Chinese are supposed to know how to read and write. Consequently, kana digraphia is of a fundamentally different nature than pinyin digraphia. Kana was required to write the Japanese language in full. Pinyin is not supposed to be required to write Modern Standard Mandarin in full.

Due to this difference, I don't see pinyin digraphia as an inevitability. As electronic technology improves, one could easily imagine how, with respect to Modern Standard Mandarin, pinyin and characters would become virtually interchangeable, in which case there is no value to digraphia – you could just convert any pinyin you write to characters, or vice versa, as needed. The question then becomes which Chinese will prefer to memorize. My money is on pinyin, but if cultural pride is high, it could be characters.

Eidolon said,

October 17, 2016 @ 4:17 pm

"I don't think romantic notions of "history and allusion" is sufficient reason to hold back a culture of a billion people."

Cultures have been held back for less. I think people tend to over rate the absolute importance of efficiency in human societies. Much of what we do is not efficient, or even rational from a scientific perspective. Productivity is rarely our most important goal, despite governments wanting to make it so. If Chinese characters are destined for the dust bins of history, it won't be because it is less efficient than the Latin alphabet, but will be the result of a particular political moment – like the triumph of the Chinese Communists, which was instrumental to the adoption of simplified characters in the PRC. It is to be observed that Taiwan, which did not experience this political moment, still uses the old, traditional characters despite its higher inefficiency.

Victor Mair said,

October 17, 2016 @ 9:41 pm

@Eidolon

You don't think efficiency had anything to do with the demise of Egyptian hieroglyphs and Sumero-Akkadian cuneiform, with the quick disappearance of the Jürchen and Khitan scripts, with the replacement of Nom by the alphabet in Vietnam, with the adoption of Hangul instead of Chinese characters in Korea? You believe those were all strictly "political" matters?

Victor Mair said,

October 17, 2016 @ 9:55 pm

@Eidolon

"Kana was required to write the Japanese language in full. Pinyin is not supposed to be required to write Modern Standard Mandarin in full."

As I have pointed out countless times before, all school children in China begin by writing just Pinyin "in full", and in some places this was allowed / encouraged to go on beyond the first grade (I've written about that several times on Language Log too).

"Due to this difference, I don't see pinyin digraphia as an inevitability."

Open your eyes; it's already emerging / happening. We are already entering an age of partial digraphia.

"As electronic technology improves, one could easily imagine how, with respect to Modern Standard Mandarin, pinyin and characters would become virtually interchangeable, in which case there is no value to digraphia – you could just convert any pinyin you write to characters, or vice versa, as needed."

People will always have a need to write things by hand, in which case they can't just flick a switch and go from Pinyin to characters or characters to Pinyin.

"The question then becomes which Chinese will prefer to memorize."

What we're seeing before our very eyes is that they are increasingly preferring to memorize what's easier, viz., Pinyin.

"My money is on pinyin, but if cultural pride is high, it could be characters."

Why are you waffling?

Eidolon said,

October 19, 2016 @ 4:08 pm

"You don't think efficiency had anything to do with the demise of Egyptian hieroglyphs and Sumero-Akkadian cuneiform, with the quick disappearance of the Jürchen and Khitan scripts, with the replacement of Nom by the alphabet in Vietnam, with the adoption of Hangul instead of Chinese characters in Korea? You believe those were all strictly "political" matters?"

I'd argue that in all of these cases, except for possibly Hangul, the political factor was more important. In the case of Egyptian hieroglyphs, it was Hellenistic conquest. With Sumero-Akkadian, it was the collapse of their respective empires/civilizations. The Jurchen and Khitan scripts met their demise as their dynasties ended and their elites were forced to work for the Mongol Empire, which used different scripts. The alphabet became widespread in Vietnam as a result of French colonial rule.

For Hangul, efficiency played a larger role in the decision but it was still associated with a major political transition in the overthrow of traditional Confucian, yanban-ruled society. In North Korea especially, Korean nationalism was instrumental to replacing the "foreign" hanja with the "native" Hangul.

In China, a similar political moment, born from 19th century European colonialism and political revolution, produced the simplified characters. But since their debut, the PRC government has become increasingly culturally conservative as well as nationalistic, as indicated for example by their cooption of traditional symbols such as Confucius. This tells me that, short of another major political revolution/crisis, there won't be any move to replace characters with pinyin, especially as pinyin is, after all, not a "native" Chinese script.

"As I have pointed out countless times before, all school children in China begin by writing just Pinyin "in full", and in some places this was allowed / encouraged to go on beyond the first grade (I've written about that several times on Language Log too)."

But my statement was not about whether they can write Mandarin in pinyin, but whether they can write Mandarin in characters. Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese cannot be fully written in characters, and the former two languages especially have characteristics – such as agglutination – that are a poor fit for the Chinese writing system. This surely is significant to the function of pinyin vis-a-vis Mandarin, and the function of kana vis-a-vis Japanese, and the function of Hangul vis-a-vis Korean.

"People will always have a need to write things by hand, in which case they can't just flick a switch and go from Pinyin to characters or characters to Pinyin."

But if they have their mobile devices nearby, as almost everyone does these days, they can quickly look them up, so character amnesia would be less of an inconvenience than if they had to check a dictionary or ask their friends. I would also argue that writing by hand will become less and less important in the future as more aspects of society are digitized, so for all intents and purposes, electronic input/output will overtake hand input/output.

"Why are you waffling?"

Because I've yet to make up my mind as to whether there will be a major political moment in China's future, which may cause characters to be abandoned in primary education. Unofficial digraphia, like unofficial scripts in general, is too ad hoc to take off as a matter of natural evolution – people don't forget the same characters, nor do they forget them every time, so how can they agree just between themselves on a standard for which characters to replace with pinyin? And without a standard, how can the script ever obtain cultural prestige? What happened to topolectical writing in China without official support is what I anticipate happening to pinyin digraphia, and to be honest, if it doesn't appear in electronic format due to automatic translation, than the chances of it appearing in future print formats are slim. I could see it being used in hand written communications as a sort of "vulgar/short hand script," but lacking reinforcement in electronic & print, it can't become the official script.

Victor Mair said,

October 19, 2016 @ 5:42 pm

"it can't become the official script."

That's not what we're talking about. What we're talking about now is Pinyin being employed in situations and for purposes where it is deemed useful. That's already happening.

Usually Dainichi said,

October 21, 2016 @ 3:34 am

'"it can't become the official script." That's not what we're talking about.'

Well, you did say

'we will look around and see […] that Pinyin will be functioning as kana does for Japanese.'

and kana is official Japanese script. Kana might be fallback when you can't remember the character, but it's much much more than that.

On a different note, I'm amused by pinyin proponents arguing for multisyllable words and capitalization but not tone marks. They seem to be shooting themselves in the foot and admitting that a semantics-influenced script can actually be better than a phonemic one. And if Mandarin were to be written in a phonemic script, then why one where dui and wei rime? Shuo and po? Why not an actually phonemic one?