Character amnesia and the emergence of digraphia

« previous post | next post »

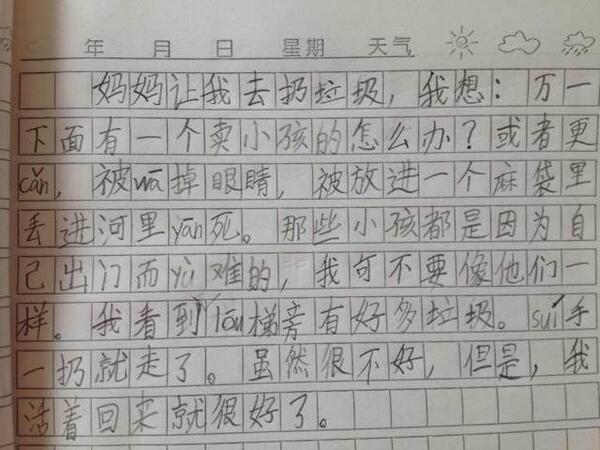

David Moser saw this photograph of a child's essay via Twitter:

Since David sent this essay to me about a week ago, I've seen it on many other Chinese sites. While we can't be sure of the age of the child who wrote it (Chinese friends estimate 3rd grade), two aspects of the essay make it interesting for anyone who is able to read it. One is the level of terror that this poor kid has to live under. He/she is afraid of having his/her eyes torn out (which an organ trafficker recently did to a six-year-old boy while playing in Linfen, Shanxi Province), of being thrown into a river to drown, etc., all the things that happen to kids in China.

The second aspect is that you can see the kid's level of character writing by the insertion of Pinyin when he / she doesn't know how to write the character in question. Apparently teachers allow students to just use Pinyin if they need to express characters they haven't studied yet or have studied but forgotten.

Here are the characters for which the child substituted Pinyin Romanization:

cǎn 慘 ("wretched; tragic; miserable; cruel; brutal; inhuman; merciless")

wā 挖 ("gouge; dig; scoop; excavate")

yān 淹 ("drown; submerge; flood")

yù 遇 ("meet; encounter")

lóu 楼 ("floor; story [of a building]")

suí 隨 ("follow; allow; comply with")

It is evident that this child's spoken vocabulary is larger than his / her ability to write characters at the same level.

There used to be a formal, and very successful, program called zhùyīn shìzì, tíqián dúxiě 注音识字提前读写 (Phonetically Annotated Character Recognition Speeds Up Reading and Writing), or Z.T. for short, which actively encouraged children to use Pinyin Romanization for characters they were unable to write. See "How to learn to read Chinese".

Whether the child has forgotten the above characters or never learned them, at the time he / she wrote this essay he / she was unable to produce them and resorted to Pinyin.

Here are some relevant Language Log posts:

Pinyin can also come in handy for words that adults know how to say but have no idea how to write:

All of these developments, spurred by reliance on IT devices, is leading to the emergence of digraphia in China, even without the intervention of government. This child's essay indicates that digraphia is already starting to happen, with students resorting to Pinyin when they cannot recall how to write a certain Chinese character.

Here is a glossary of up-to-date internet terms, most of which are not to be found in standard dictionaries. It is conspicuous how many of the entries in this glossary are non-Sinographic, being derived from English and written in Pinyin or even with numbers (which are being used for their sounds) instead of characters.

Another form of digraphia that is taking place in the Sinosphere is that between Mandarin in Taiwan and in Mainland China.

All of these developments evince a healthy focus on successful written communication without regard to a single, rigid form of writing.

[Thanks to David Moser]

Brian O'Connor said,

September 25, 2013 @ 2:00 pm

Has there ever been a serious movement in China to fully move over to pinyin, or any other way to represent written Chinese using an alphabet?

I understand that the financial cost would be enormous, as well as the cultural cost of involved in cutting Chinese people off from their written history.

cameron said,

September 25, 2013 @ 3:46 pm

Didn't the Chinese already "pay the cultural cost . . . involved in cutting Chinese people off from their written history" a hundred years ago when they switched to writing modern Mandarin rather than classical Chinese?

Would the cost be greater this time around if they were to emulate the successful Turkish experiment and go for full romanization?

At this point they'd be just cutting themselves off of their 20th century history, which they seem rather eager to forget in many cases anyway.

Nuno said,

September 25, 2013 @ 4:00 pm

Presumably Chinese kids would still learn a large amount of characters for a long time. They just wouldn’t be required to know how to write “all” of them for basic literacy. Not unlike what has happened in Korea.

“我活着回来就很好了” is absolutely heartbreaking.

R. Sode said,

September 25, 2013 @ 4:44 pm

With the wide use of computers and the roman character input, for the last couple of decades the Japanese have experienced increase in kanji characters they can read but not write, at least not off the top of their head (even if they learned them in school at some point in the past). As long as the writers can visually recognize and choose the correct characters when typing in the word processing program, they do not need (or feel the need) to know how to write everything. That has been my personal experience and, anecdotally, the trend among many Japanese, although I have not come across any research done on this subject matter. As correct and esthetically pleasing hand-writing is still highly estimated in Japan (and I imagine in China too), schoolchildren will not be told they don't need to learn to write in Chinese characters, at least unless/until the system changes. In the meanwhile, the use of computers will make it easier for literacy to be attained, so long as handwriting is not required in all situations.

George Grady said,

September 25, 2013 @ 4:51 pm

Is there a rough translation of the essay available somewhere for those of us unable to read the original? My googling is inadequate.

Youmei said,

September 25, 2013 @ 5:29 pm

Translation:

Mom told me to take out the trash, and I thought: What will I do if there’s someone outside who sells kids? Or worse, my eyes could be gouged out, or I could be put in a burlap bag and tossed into the river to drown. Those kids all ran into trouble for going out alone, I for sure don’t want to be like them. I saw a lot of trash next to the stairs. I simply tossed mine over and left. Although this wasn’t very nice, still, it’s enough for me to just get back alive.

Victor Mair said,

September 25, 2013 @ 5:55 pm

@George Grady

Here's a rough translation:

Mother had me go throw out the garbage. I thought: "What if there happens to be a child-seller downstairs? Or, much more terrible, what if I get my eyes gouged out or am tied up in a burlap bag and thrown into a river to drown? When those things happened to children it was all because they went out by themselves and were victimized. I certainly don't want to end up like that! I saw that there was a pile of trash next to the stairs, so I just willy-nilly threw down the garbage and left. Although that wasn't good, at least I'm lucky that I came back home alive."

Chris Barts said,

September 25, 2013 @ 7:06 pm

@Nuno:

"I come back alive on the good." Heartbreaking, all right.

dainichi said,

September 25, 2013 @ 7:56 pm

Are the hanzi that schoolchildren must study at a given grade decided by a central authority, similar to Japan? Just wondering what hanzi a 3rd grader would be expected to know.

phspaelti said,

September 25, 2013 @ 8:23 pm

@dainichi: they are overwhelmingly different. In Chinese many characters that are considered basic and are very frequent are hardly used at all in Japanese. This is (mainly) because Japanese uses Kana to express those things.

Victor Mair said,

September 25, 2013 @ 8:38 pm

@Chris Barts

Nuno knew what it really meant, and that is not what you got from Google Translate.

Victor Mair said,

September 25, 2013 @ 9:01 pm

@Peter

The students from the PRC in my class all were taught Putonghua (Modern Standard Mandarin [MSM]) and can speak it fluently. A few of them are also capable of speaking a local topolect, but when they do that it sounds very different from when they're speaking Putonghua. The individual variation which they displayed when saying their versions of gē'ermen 哥儿们 was all within Putonghua. I must stress again that I did ask several of the students who could speak a non-Putonghua topolect to pronounce the word gē'ermen 哥儿们 in their local language and then it sounded much different. The speaker from the Chongqing area is an auditor over twice the age of most of the students, so his training in Putonghua was not nearly as good as the young students. Consequently, his pronunciation of gē'ermen 哥儿们 was more strongly influenced by his native topolect, though he was trying to speak Putonghua for the class. When he speaks real, unrestrained, earthy Chongqinghua, it would be well-nigh incomprehensible to someone who speaks only Putonghua. This is partially borne out by the following articles — which, by chance — I received today.

Inventing new characters for the language of Chongqing

http://cq.cqnews.net/shxw/2012-03/07/content_13574045.htm

http://cq.cqwb.com.cn/NewsFiles/201202/08/870278_1.shtml

As one of our classmates notes, these characters are "barely in accordance with liushu 六书. This not only reminds us of the real origination of some so-called suzi 俗字 that are quite popular, though not officially recognized, but also tells us that the gap between a scholar's idealistic construction and reality is so vast that once in a while we should leave the old papers aside and actually open our eyes to find out what is happening around us."

Victor Mair said,

September 25, 2013 @ 9:23 pm

Perhaps I should note that yīgè mài xiǎohái de 一个卖小孩的 ("a person who sells children") is a shortened form of yīgè guǎimài xiǎohái de 一个拐卖小孩的 ("a person who abducts and sells children"). This is, of course, a type of trafficking, as is the gouging of eyes for their corneas.

JS said,

September 25, 2013 @ 11:48 pm

@dainichi

For primary school in the P.R.C., the 《现代汉语常用字表》 of 1988 is often taken as approximate standard; it contains 2500 so-called "常用字" (often said to cover 98% or whatever it is of what's encountered in "各类读物" ) and 1000 additional "次常用字." The tables I have seen online breaking this down by grade level (called things like 《小学X年级常用汉字生字表》 ) are consistent in offering 350 characters for Grade One, 500-odd for Grade Two, and 620-odd for Grade Three, for a total of around 1500 characters.

Out of curiosity, I checked some example tables and found that of the six morphemes written in pinyin above, 楼 appears in the Grade 2 table (if indeed a third grader, shame!–though perhaps it is non-obvious that the first syllable of 'stairs' should be so written),with 挖, 随 and 惨 in the Grade 3 table (Prof. Mair's students may really have pegged the grade level?) 遇 and 淹 appear later in the ~2500 (with total characters contained in the Grades 1-6 tables I checked really numbering 2360ish.)

So, lots of characters. Incidentally, my daughter was encouraged to use pinyin in the same way when in school in China; I do the same with students here. Digraphia of a highly restricted kind, but digraphia nonetheless…

JS said,

September 25, 2013 @ 11:56 pm

More trivially — this pertains to a debate I've been having with myself about how to present digraphic texts to students: if they know both of the words lóu 'building' and lóutī 'stairs' but only the character 楼, for example, should I write the word 'stairs' in the context of reading comprehension exercises and the like as <楼tī>, or rather as <lóutī> to emphasize the word unit?

JS said,

September 25, 2013 @ 11:57 pm

^ 楼tī vs. lóutī

John Rohsenow said,

September 26, 2013 @ 12:08 am

"Apparently teachers allow students to just use Pinyin if they need to express characters they haven't studied yet or have studied but forgotten."

This was of course a central part of the "Zhu Yin Shi Zi, Ti Qian Du Xie"

experiment championed by Zhou Youguang and the late Yin Binyong of

which I wrote about in the CLTA. I also analyzed the HYPY spelling mistakes ina bunch of grade school student papers in some schools using this expmt. that Yin and I visited about 1985. After the Lang Reform Commission wasmerged into the Jiaoyubu, and the "Z-T" expmt.

was sidelined, I think that this is one of the surviving remnants of having the insights of that experiment mainstreamed. JSR

JS said,

September 26, 2013 @ 12:29 am

@Chris Barts

Wow, X就好了 and the like seem to give Google Translate serious and weirdly unpredictable problems…

我被挖掉眼睛 is the kind of thing you know will be wrong and how; predictably, it gives "I was gouged out eyes."

Rebecca said,

September 26, 2013 @ 4:50 am

This is OT, but why does the writing paper have little weather symbols at the top of each page?

Victor Mair said,

September 26, 2013 @ 5:31 am

@Rebecca

Not off topic at all.

Across the top of the page, there are spaces for the student to write: year / month / day / day of the week / weather, for which they simply have to circle one of the three conditions for the day in question.

Observation said,

September 26, 2013 @ 5:33 am

I just wanted to make a couple of… observations. (I actually picked that name because the first time I commented, I assumed the first line said 'title', and typed in 'Observation'.)

Firstly, this is a diary entry. In Chinese, all diary entries indicate both the date and the weather on the top line. The child didn't fill these details in, though.

Secondly, the handwriting seems fairly mature. I think the writer should be around the 7-10-year-old range (older children would probably write longer entries). Interestingly, the characters missed seem pretty basic for that age. I understand if (s)he missed one or two, but six seems a bit too many…

Incidentally, in primary school, especially for P3 and below, we were allowed to substitute characters for pinyin too. (I'm from Hong Kong, but I'm very young and I entered primary school post-handover.) We did lose a mark every time, the same penalty for wrong characters. The Education Bureau seemed annoyed about this phenomenon last TSA…

Little Johnny said,

September 26, 2013 @ 5:44 am

Oh, come off it Prof Mair!

I suppose a vastly experienced sinologist might be forgiven for not having his finger on the pulse of Chinese internet culture, but surely you could exercise a little skepticism before offering us something like this as evidence of anything meaningful.

These little children's essays have been a staple of Weibo and other platforms for years now. They frequently cram in several of the latest scandals and, thus, make a point. But nobody seriously believes they're written by children.

JS raises some sensible questions about when certain characters are learned, but the whole thing could only be read in a cartoon voice.

Even the handwriting wouldn't stand up to scrutiny – notice how some of the 'heng' horizontal strokes are remarkably accomplished, and the little flourish on 可?I know some young kids with respectable calligraphy, but this looks like it might well be an imitation of a child's writing.

As for the pinyin…that's a nice touch.

Victor Mair said,

September 26, 2013 @ 6:19 am

@Observation

"Incidentally, in primary school, especially for P3 and below, we were allowed to substitute characters for pinyin too."

Did you mean to write "Incidentally, in primary school, especially for P3 and below, we were allowed to substitute pinyin for characters too"?

Victor Mair said,

September 26, 2013 @ 6:27 am

In my original post, I had intended to mention that the Pinyin syllables in each case are marked with tones. I also wanted to mention that a lot of the characters are ill-formed or poorly proportioned, e.g., mài 卖, such that I (not as familiar with simplified characters as with traditional ones) had to spend a little bit of extra time to figure out what they are.

Victor Mair said,

September 26, 2013 @ 6:34 am

I was very glad that John Rohsenow added his voice to what I wrote about the Z.T. experiment (the remnants of which are surely operative in this essay) in my original post and in other Language Log posts, since he has been its greatest expositor outside of China. During the 80s and early 90s, my wife was actively involved in various Z.T. programs around China, and she found them to be singularly successful in helping both young children and adult illiterates to learn to read more quickly than if they were restricted to characters alone.

I should also note that I was fortunate to meet Ni Haishu, the most ardent advocate of Z.T.-type programs, in the early 80s before he passed away.

Rodger C said,

September 26, 2013 @ 7:28 am

@phspaelti: That's not what dainichi asked, though the question's syntax is misleading. Is there an authority in China, like in Japan, that mandates what characters are to be mastered in each grade?

JS said,

September 26, 2013 @ 8:08 am

@Rodger C

Addressed dainichi's question to some degree above

@Little Johnny

We've debated on here before about how genuine these "children's essays in the news" are likely to be; hard to prove one way or another re: any particular case. I'm generally a skeptic but see no reason this one absolutely couldn't be real…

JS said,

September 26, 2013 @ 8:19 am

On re-examination, more convinced it's a child's writing — the artful horizontal stroke is taught explicitly and is a part of still younger kids' calligraphic arsenals; not sure what you mean about the "flourish" in 可. The generally good mechanics + shaky sense of proportion would not be easy to imitate so uniformly… notice also both instances of 垃圾 have been corrected in the same way.

JS said,

September 26, 2013 @ 8:20 am

^and that both 垃 and 圾 are learned post-3rd grade

Little Johnny said,

September 26, 2013 @ 9:52 am

@JS A very reasonable analysis. I think these little essays – diary entries, as pointed out above – are very interesting in their own right. But I wouldn't pause for a moment to consider them as 'genuine'. Once you do, you might easily convince yourself that they could be. And, of course, in part or in full, they could be.

Looking at the hand writing itself is interesting enough. How sure can we be?

As you have pointed out, there are plenty of signs in here of practice at the fountain pen 钢笔 style of writing. I would note that several characters are extremely well formed (自,们, 眼睛 etc), some in which one element seems rather better written than the other (妈,去), other characters are downright delinquent (圾,的). I note that the 隹 in 难 is really very nicely done too. My point about 可 was the little down-left lead-in to the top horizontal, but maybe that was just a scratch.

I think there is serious inconsistency in the handwriting which, though one might think of a wayward child doing his homework badly, is most likely to point to an imitation.

But surely the first thing one does on reading this kind of thing is hear a funny little kiddie voice – amazingly (implausibly?) aware of precisely the issues which have stimulated so much discussion in recent weeks, speaking in a very cute and juvenile way – and then the punchline 我活着回来就很好了!!!Even the handwriting suggests that the author rushed through it a little too gleefully.

Is it possible that this was dictated to a child, and the child was told to write pinyin if he didn't know the character? Sure!

But then, I see no reason to start from that perspective at all. It's an amusing little online joke – a piece of slightly dark humour, nicely making a point about what a state society is in. Or maybe it's an effort to further instill fear and distrust in an already wary population!

Of course. with millions of young Chinese kids, with millions of pens and millions of pieces of squared paper, every day writing their little diary entries, it's only a matter of time before one of them, scribbles the complete lyrics to "I Like Chinese."

Victor Mair said,

September 26, 2013 @ 9:58 am

From a colleague who has taught Chinese in college for over 40 years:

Do you remember the old Yale IFEL readers? Read Chinese I had what you call "digraphia." It was later rejected as "the rebus method," but I liked it for putting speaking ahead of reading and putting all the characters it introduced into context. There was a regular number of characters per lesson (10? 15? 20? — I forget) adding up to 300 by the end of the book–and that's the 300 Fred F.Y. Wang's Lady in the Painting was based on. Language textbooks have changed a lot, but I'm not sure it's for the better.

Victor Mair said,

September 26, 2013 @ 10:04 am

I've asked a number of professional Chinese language teachers to comment on the probable age of the individual who wrote the above essay and will share them with LL readers as they come in.

Here's the first:

The characters are better formed than those of most 3rd grade Chinese kids, in my experience. My guess would be this is either a somewhat older child – 5th grade perhaps? – or a 2nd or 3rd grader from a well-to-do family who has had supplementary training (maybe even calligraphy) outside of regular elementary school.

Victor Mair said,

September 26, 2013 @ 11:10 am

From teacher #2:

From the content, I believe the student is around upper elementary school (5th-6th grade and up).

Victor Mair said,

September 26, 2013 @ 12:04 pm

From teacher #3:

This seems to be written by a 2nd or 3rd grader, in my judgment.

VHM: I should note that ALL of the teachers whom I have contacted have between 20 and 50 years of experience.

Victor Mair said,

September 26, 2013 @ 12:14 pm

From teacher #4:

handwriting: A-

language: A

content: A (It is definitely the child's fault to have so negative ideas! He is already the victim of the society! Poor child!)

Victor Mair said,

September 26, 2013 @ 12:17 pm

From teacher #5:

From the content, I believe the student is around upper elementary school (5th-6th grade and up).

Victor Mair said,

September 26, 2013 @ 2:17 pm

From teacher #6:

I think this student may be about 10 years old, the 4th grade in elementary school because the handwriting looks nice. Or maybe younger because he/she used a pencil rather than a pen. I remember I was required to use a pen to do my home work when I was in the 4th grade.

Victor Mair said,

September 26, 2013 @ 2:44 pm

From teacher #7:

Is this from a big city school or a semi-rural school? I don't know what to expect from Chinese elementary education nowadays , thus it is difficult to judge. My guess is the child is between 4th-6th grade. I could be completely wrong.

paulr said,

September 26, 2013 @ 6:17 pm

I’m firmly in agreement with Little Johnny’s scepticism. It’s far too well constructed and pithy not to be a fake.

And, like many a Daily Mail story, the one Prof. Mair links to turns out to be substantially inaccurate, inasmuch as the culprit wasn’t an organ trafficker, but the boy’s aunt who subsequently committed suicide, nor were the boy’s corneas removed. In fact, the case had nothing much to say about Chinese society at all.

Victor Mair said,

September 26, 2013 @ 6:44 pm

From a Hong Kong graduate student:

I would guess a fifth/sixer grader.

Victor Mair said,

September 26, 2013 @ 6:45 pm

From one of my graduate students whose mother has been the principal of an elementary school in Hunan for thirty years:

My mother said that it might be the diary of a student in the third or fourth grade. And I agree with her.

Victor Mair said,

September 26, 2013 @ 7:02 pm

Many of my PRC graduate students have weighed in, and they all say between 3rd grade and 6th grade. Not one has evinced any skepticism. The only respondent who raised the slightest doubt about the content is someone who left China about 35 years ago and has been living in North America since that time.

Ziyao said,

September 26, 2013 @ 8:54 pm

It's common for kids not remembering certain characters and substituting them with Romanization. This phenomenon existed before the "Computer Age". After the pupils going to senior grades, their teacher will force them to use characters. This is how we are trained. We call this process the "weaning" of using Romanization. Of course in case of "amnesia" we still use Romanization, but this is deemed as "wrong" or very informal, and doing so gives us an impression of illiteracy.

Indeed, after computers went popular, I feel that I'm not so familiar with characters anymore. Learning Japanese (we have to hand in the Kanji sheets) reminds me how long I haven't written any characters (except for signing my name on receipts). Maybe things are changing in a rather unforeseeable way. Still, I think the total disappearance of characters in the future is an idea too radical to me.

Victor Mair said,

September 26, 2013 @ 9:16 pm

From a lexicographer in Shaoxing, Zhejiang Province:

Written by a student in grade 3? My wife says that only from 3rd grade do students start to write compositions; they're still not writing compositions when they're in 2nd grade.

三年级的学生写的?我妻子说,三年级的学生才开始写作文,二年级还不写作文.

Mark S. said,

September 27, 2013 @ 5:02 am

"It is evident that this child's spoken vocabulary is larger than his / her ability to write characters at the same level."

It's worth noting that, to one degree or another, this is true for basically every single person in the whole of China.

Victor Mair said,

September 27, 2013 @ 6:24 am

From a language pedagog in Beijing:

Cela correspondrait au niveau d' un ecolier de 3e ou 4e annee.

Jiancheng XUE

professeur a l'Universite des Langues etrangeres de Pekin

Victor Mair said,

September 27, 2013 @ 8:24 am

From a Chinese lexicographer in America:

My guess would be 4th grade, maybe 3rd.

Anthony said,

September 27, 2013 @ 3:00 pm

Paulr – it doesn't matter whether the story was true or not, but whether it was circulated in China in the form the child wrote about. Because an elementary school child probably won't have the critical faculties to question whether the story was, in fact, reported accurately by whatever scandal sheet his/her parents or teachers read. Would you expect a 5th-grade English student to write about his fears, and get details right which the Daily Mail got wrong?

paulr said,

September 28, 2013 @ 5:16 am

@Anthony – By starting my second paragraph with “And”, I must have misled you. I didn’t intend any implication at all concerning whether or not the supposed author had seen a report of this case. In any event, it wouldn’t have been the Daily Mail.

I just didn’t want to let Prof. Mair’s comment stand concerning what “an organ trafficker recently did”, since we now know he didn’t.

However, in response to the question as to whether our putative second grader who’s had supplementary calligraphy training, or he may be a sixth grader or up, but we’re unable to say, actually read the misreported case of a boy’s corneas being plucked out, during the few days before the report was widely denounced as inaccurate and corrected, and, rather than being traumatised by it or putting it out of his mind, such is “the level of terror that this poor kid has to live under”, was able to assimilate it, along with another story about a boy being disposed of in a sack in a river for which no evidence has been produced, as an exemplar of an existential risk to his age cohort, which terrified him, but not sufficiently that he was incapable of working it into a well-crafted story that, purportedly justifying why he didn’t take the garbage out properly, made an amusing comment about the supposed risks to juveniles in contemporary society, and that, by some unknown route, found its way onto the internet, that familiar source and storehouse of mostly anonymous round-robins and titillations of dubious veracity, I say pull the other one.

Victor Mair said,

September 28, 2013 @ 7:08 am

@paulr

You might be surprised at the way Chinese parents, relatives, and neighbors talk about the horrible things that befall little children (eye-gougings [it didn't happen just once recently], molestations, school-knifings, abductions, food poisoning…). News of these things fly around the community and the nation very quickly — even without the internet. I've lived in China for a long time, and David Moser — who sent the essay to me and commented on it, after discussing it with his Chinese colleagues at a language and culture program in China — has lived there a lot longer and brought up his daughter there, and we've heard people talk about these terrible tragedies in the presence of their children. You don't think that the children would be affected?

Finally, why did you choose to use such an impenetrable style for your long third paragraph (all one convoluted sentence) — a style that vies with that of Fredric Jameson and James Joyce for its logic-straining complexity and intricate impenetrability? Were you attempting to bludgeon Anthony and your other readers into submission with its turgidity, especially since you know that Chinese teachers, educators, linguists, graduate students, and others have not been expressing the same arch skepticism as you?

After all of those clashing clauses, I wonder how many readers who struggled through to the very end could comprehend what you were getting at, and whether you yourself remembered what you meant by that final, opaque clause.

Little Johnny said,

September 28, 2013 @ 8:20 am

Professor Mair,

This is all getting rather silly.

Imagine for a moment that a professor of media studies at a renowned Chinese institution produced an article discussing the obvious increase in the use of passive voice by American journalists – something he's long viewed as an significant trend – and for evidence produced a report from The Onion.

Does an Onion report look like a real news report? Sure! It has a headline, and a byline and probably employs those six honest serving-men 'what, why, when, how, where and who' early in the piece.

Might the Onion provide insights into American journalistic culture? Hell yes!

Would it be a good source employ when seeking to demonstrate a technical point about current language use by American journalists? NO! And I presume that were you to stumble across such an article you would giggle childishly, just as Little Johnny did when he read your analysis.

If nothing else will convince you, perhaps you could read your translation to an American elementary school teacher and ask them what they would think if one of their kids submitted this as homework.

paulr said,

September 28, 2013 @ 8:36 am

@VM My long sentence was a rather arch stylistic device to suggest that the complex totality of the aspects of this story you need to believe for it to be true make it far less credible than the parsimonious explanation, i.e. that it’s a fake. Sorry it didn’t amuse you, but it parses correctly.

Of course, I’ll enjoy recounting the fact that my style has been compared to James Joyce by a world-famous professor. I won’t say it wasn’t said as a compliment though, and by the third time of retelling James Joyce will have become someone more stylish, say Henry James. But who’s to know? Which is really my point.

I don’t doubt that your correspondents gave an accurate assessment of supposed age of the author, based on content and character production, although there was quite a range. But no-one looked at the totality of the “production”. Of course, I don’t know it is a fake, and I’m not trying to bludgeon anyone to my view. It just seems overwhelmingly likely based on my experience of the internet and, well, human nature.

When I was a boy, I wrote a “what I did on my holidays” story which included the sentence “I put my pennies in the slot machine”, which the teacher duly ticked as OK. But I’d spelled “pennies” without the second “n” and the second “e”. I don’t know what she imagined I’d been doing. Is this story true or false?

Janet Williams said,

September 28, 2013 @ 10:26 am

Not to try to turn this post into a parenting issue, I used to be 'threatened' by many adults — "if you do XYZ, police will come and get you,' or 'ABC will happen to you,' or, 'you will be caught/sold.' It was common to be scared, to be told real or exaggerated stories so that a child would behave. I come from a typical traditional background, and harsh language is common. I believe many Chinese kids are not insulated from the threat of violence and human depravity.

Janet Williams said,

September 28, 2013 @ 12:44 pm

I was not lucky enough to know about the zhùtí (Phonetically Annotated Character Recognition Speeds Up Reading and Writing) method. My learning purely focused on character recognition. Any form of annotation on paper was discouraged, as teachers did not like to see them.

I learnt Zhuyin in the 70s in Malaysia. However, Zhuyin was not systematically taught, as teachers were not all qualified. We simply copied our teachers' pronunciation. Whenever we didn't understand a character in writing, we would leave a blank space, draw a circle, or write part of the character.

A lot of us would make out our own spelling system, for example, making out a Malay sounding word to match the sound of the Chinese character. I pronounced many characters incorrectly for years as I didn't master Zhuyin, and pinyin was not taught in my high school when I left in 1986.

I understand that since the late 80s, pinyin has been more systematically taught.

Now I can see how practical it is to have a consistent system (Zhuyin or Pinyin) to enable learners to help themselves. My Indonesian friend shared how they use a transformation from Dutch-based spelling into Latin-based spelling in annotating Chinese character. Fascinating!

Janet Williams said,

September 28, 2013 @ 1:04 pm

Could you enlighten me if Chinese children possibly miss out on the joy of reading storybooks, compared with most western kids?

I'm not sure what kind of storybooks kids in China read. How do they overcome the difficulty in characters, and still enjoy reading?

English kids have the luxury of reading carefully graded storybooks. The reading skill and the confidence they build up prepare them to read fictions independently by the age of 10 approximately.

Do you think the extensive use in pinyin with characters may promote the joy of reading stories? Is there a link?

julie lee said,

September 28, 2013 @ 1:25 pm

@Little Johnny, @paulr, @Janet Williams:

1. re: whether the handwriting was that of a 8-11 yr. old. I had no doubt it was that of a child. My own handwriting at 8 (which I found in rummaging among old papers) was like that. I've had letters from adult Chinese friends for more than 50 years, and none of them had such poor hand-writing as in the sample in Victor Mair's LLog. The sample is obviously from a juvenile.

2. re: whether the essay is hat of an 8-11 yr old. Language-wise, very possibly, because, remember, in the old days (as late as early 1920s), an 11-yr-old boy from a good family had already memorized the classics for at least 5 years. ll-yr-olds sometimes passed the first-level civil service exams and got the XIU-CAI degree (like our Bachelor's), and sometimes even passed the next-level got the JU-REN degree (like our Master's). My mother had a neighbor in New York in the 1980s whose 10 yr old son had read all the great Chinese novels, "Dream of the Red Chamber", "Romance of the Three Kingdoms", "Water Margin", "Forest of Scholars". and spoke beautiful literate Mandarin. I'd say, neever under-rate an 8 or 10 year old. I'm sure many Western children are the same.

3. Re the content of the sample: The language of the sample is completely in ordinary conversational Mandarin, and the content is something that children will be hearing from their parents or other adults, or other children. When I was a six-yr-old in Hong Kong grown-ups at home told me about robbers' cutting off ladies' fingers for their diamond or jade rings, and of children being kidnapped. Now, in America, I tell the children and grandchildren to be sure to lock windows and doors at night because children have been reported snatched from their beds (and even from their tents at a summer school), or killed when alone at home, here in the San Francisco Bay Area. The sample essay from a Chinese child, grim yes, implausible no.

Little Johnny said,

September 29, 2013 @ 6:07 am

@julie lee

Thank you for your insights. I'm sorry for the lengthy response!

Alas, I've seen many an adult's handwriting that would not impress alongside this supposed sample of childish writing, but that's neither here nor there! I can accept too that there are 'ordinary' eight or nine year olds whose calligraphy would indeed stand well next to some of the more neatly formed characters in this 'sample'.

I'm afraid I came to a close examination of the handwriting from, perhaps, a position diametrically opposite to yours; I assumed it to be an imitation from the beginning.

If I were to be presented with a piece like this and asked who might have written it, I would immediately note the pinyin, and the obvious difficulty the writer has had with a number of the characters he was able to write, and conclude that the writer must be young, and just starting out on the long journey toward mastery of the pen.

However, I assumed it to be 'fake' and asked a quite different question:

Is this really the work of a young-ish child?

Approached from this angle, I think that some interesting features jump out:

1) Some of the characters are practically scratched on the page – they look like the work of someone fighting the pen.

2) A number of characters are actually quite respectable imitations of the kind of script many kids practice relatively early on.

3) A few of these 'better styled' characters are actually quite nicely written, and ought to earn a pat on the back.

4) There are several characters, indeed a couple of sequences of characters, which are formed with a balance and ease – fluidity – that I think takes a lot of practice, and only really develops once the child begins to really put the language to use, instead of simply practicing writing.

To see elements 1) and 2) together on the same page might not seem especially surprising. I'm sure we could rationalise that the child was indeed having calligraphy lessons at a time when they had a very limited 'literacy'.

Once we see elements 1), 2) and 3) together, I think we may start to have doubts. Would a child that takes such obvious pride in writing certain characters really still struggle so much with some of the others? Indeed, would she willingly leave pinyin in the place of so many other everyday words? I have my doubts, but no doubt we could spin a story to explain this. Poor kid struggling away over her homework in the back of her parents' restaurant, no access to a dictionary, parents too busy to help, love of language, sometimes encouraged by grandparents who're not here tonight…etc.

But taking elements 1) – 4) together in the same piece, I think it almost totally implausible that this is the sincere written work of one hand. If we start to consider that someone helped a child to write their homework then all sorts of issues arise.

The simple explanation would seem to be that this is the work of someone imitating a child and, though the mask clearly slips in places, it's certainly been good enough to summon the sound of a childish voice to Little Johnny's ear, and to the ears and many others.

Regarding your point about outstanding children and the expectations of times gone by…

In some ways it's sad to think of how little we typically expect of kids these days, both in the East and in the West. That said, there are certainly still plenty of children encouraged, supported or bullied into achieving great things at a very young age.

The child prodigy remains something of a fascination for society at large…like something from a freak show. But it's interesting that one of the first things that springs to mind when talking of such a creature is an immense level of literacy; a child that has devoured, and can recycle, the classics.

Of course there is no-one who could have read "Dream of the Red Chamber" yet still be unable to write 'stairs'.

Even if we accept a near-illiterate child prodigy – someone who through great sophistication in some field which requires neither literacy nor a full adult form, but mixes with adults and has an adult mind – then this could just be the work of such a child. But it would no longer seem appropriate to view it as 'the voice of innocence'.

The language is indeed very much ordinary conversational Mandarin; easy and unfussy; and, at the beginning, at least, somewhat childlike.

Of course, the reasoning, the logical chain and its development, are anything but juvenile.

This is obviously not the unadulterated work of a child. That said, I can't be sure that no children were harmed in the telling of this story.

Victor Mair said,

September 29, 2013 @ 7:19 am

From a college instructor in Taiwan:

After I have done some research, since 淹 yan1 is taught in the fourth grade of elementary school in Taiwan, this student might be under the fourth grade. Especially when this essay was written in Simplified Chinese, the student might be in Mainland China. Therefore, it might be better if we could obtain the textbooks from the elementary school in Mainland China to make a better judgment.

Victor Mair said,

September 29, 2013 @ 8:19 am

I have been urged by my Language Log colleagues not to feed trolls, so I will try to keep this brief.

It is sad when serious discussion of character amnesia and emerging digraphia is hijacked by sarcasm and rudeness.

Remarks such as these speak for themselves:

=====

"Oh, come off it Prof Mair!" [beginning sentence of one individual's initial comment]

"As for the pinyin…that's a nice touch." [end of the same comment, which totally ignores the fact — testified to by many of the commenters and by all of my Chinese graduate students — that Chinese children (and sometimes adults too!) often substitute pinyin for characters they don't know]

"This is all getting rather silly." [beginning sentence of another comment by the same individual]

"Of course there is no-one who could have read 'Dream of the Red Chamber' yet still be unable to write 'stairs'."

"I assumed it to be an imitation from the beginning."

"…and to the ears and [sic] many others." [there was only one other]

"Of course, I don’t know it is a fake, and I’m not trying to bludgeon anyone to my view."

etc.

=====

JS, who is incredibly smart, speaks beautiful Mandarin, is bringing up two young daughters to read and write Chinese, and who is by nature quite a skeptical person, devoted a lot of effort to the precise analysis of the characters and pinyin in the essay, but all that he wrote was like water off a duck's back to the person who "assumed it to be an imitation from the beginning".

It is difficult to engage in a meaningful conversation with someone who speaks of himself in the royal, pseudonymous third person and refuses to budge in the slightest from initial, snap assumptions, even when confronted with different opinions put forward by numerous Chinese educators, professional language teachers, graduate students, and others.

I am grateful to julie lee, Janet Williams, John Rohsenow, Anthony, Mark S., Ziyao, Rodger C, Observation, Rebecca, phspaelti, dainichi, Youmei, George Grady, R. Sode, Nuno, cameron, Brian O'Connor, and all the others who have made meaningful contributions to this discussion and helped to keep it on track.

Little Johnny said,

September 29, 2013 @ 10:23 am

Professor Mair,

I have no wish to upset you or anyone else.

Both JS and janet lee have made useful, insightful comments both here and on other articles, and I very much hope they will continue to contribute so positively in the future.

I do however think it most unfortunate that you chose material of this nature to illustrate a point about developments in script use.

Best wishes to you.

Little Johnny (Grade 3)

JS said,

September 29, 2013 @ 3:16 pm

I agree it is a pleasure to imagine oneself capable of sniffing out artifice which snookers the more gullible… so seeing as material of this nature certainly exists and that it certainly on some level represents digraphia, is your insistence, Little Johnny, simply insistence on your own sophistication relative to others? Is this one fake, too?

julie lee said,

September 29, 2013 @ 5:25 pm

Little Johnny,

Thanks for your long response.

–jl

Victor Mair said,

September 29, 2013 @ 9:00 pm

@Little Johnny

"Both JS and janet lee…"

That's julie lee and Janet Williams, not janet lee.

Little Johnny said,

September 29, 2013 @ 10:56 pm

@JS I thought your analysis of the apparent anomalies in the pinyin was most helpful, and certainly sufficient to cast serious doubt on any claim that the use of pinyin could not be that of a child.

I honestly admit that I enjoy that kind of analysis. Though my own attempts to show that there remained serious doubts about the handwriting have obviously fallen short.

With regard to the item you have linked to; had the professor used this to illustrate pinyin use by children, I would not have doubted it for a moment. Am I being set up for a fall?

@ Victor Mair Three compliments for the price of two!

My sincere apologies for Janet and Julie for confusing their names.

hanmeng said,

September 29, 2013 @ 11:59 pm

Speaking of digraphia, in Taiwanese subtitles to TV programs I sometimes see zhuyinfuhao mixed with Hanzi to represent Holo ("Taiwanese") sounds. LIke ㄟ

Victor Mair said,

September 30, 2013 @ 8:02 am

From the editor of a linguistics journal in Hong Kong:

After consultation wish friends more familiar with mainland schools, we guess that the piece is written by a primary 1 (second term) or primary 2 (first term) student.

Victor Mair said,

September 30, 2013 @ 1:32 pm

For an example of children's literature that terrifies children, see:

"妈妈杀了我爸爸吃了我:恐怖少儿读物谁来管"

The title is so awful that I'd rather not translate it.

http://say.cqnews.net/html/2013-09/29/content_28061380_2.htm

RadioSilence said,

October 24, 2013 @ 3:15 pm

As someone with limited literacy in Mandarin but more or less fluent 口語, I can attest that with my level of practice (which is probably about the same as this kid's), some of my characters look beautiful and the others like deformed abominations. As for using pinyin as a substitute for stuff I don't know, I used to do that, but I find it aesthetically jarring and try to use zhuyin (bopomofo) or homophones instead. Some of my written musings look a little like Japanese due to so much zhuyin peppered in them.

Nirvana said,

December 3, 2013 @ 7:12 am

I am from Mainland China. My daughter once wrote such compostions. I asked her why she wrote in pinyin instead of the Chinese character. She explained that her teacher asked her to write so if she did not know how to write the exact Chinese character. Certainly she knew how to speak at that age, but simply had not learned how to write the character.

Nowadays it's common that Chinese people forget how to write Chinese owing to the fact that they seldom write because of using computer.

And in mainland China, because of using simplified Chinese characters, the majority of Chinese people, including the well-educated, do not know the traditional Chinese Characters, and the traditional Chinese culture as well.

Nirvana said,

December 3, 2013 @ 7:37 am

It is great that prof. Mair could translate Zhuang Tzu and Lao Tzu into English, but even for the majority of well educated Chinese people, Zhuang Tzu and Lao Tzu are beyond their understanding. Famous English professors in famous Chinese universities who translated the two books into English, as far as I know, are no exception at all.