A child's substitution of Pinyin (Romanization) for characters

« previous post | next post »

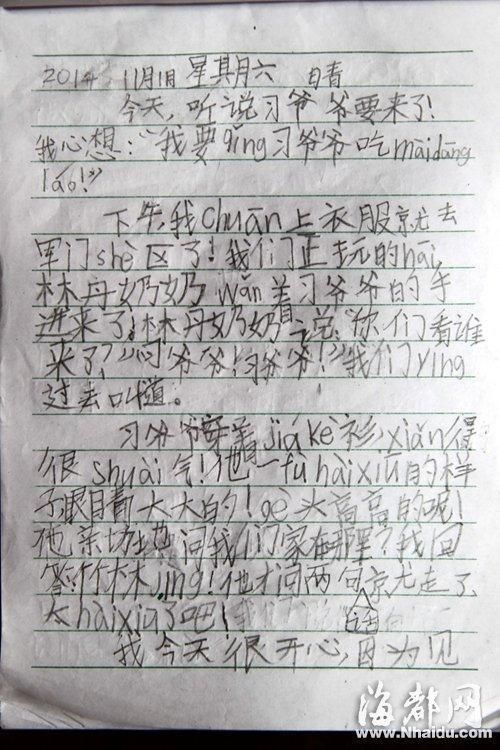

The following diary entry by an elementary school student is making the rounds in the Chinese media and in the blogosphere:

Jacob Rutherford, who called this "trending post" to my attention, remarked:

[It's] about a young girl from Fuzhou whose school received a visit from Xi Jinping. Besides the adorable message, it is more interesting evidence of how Chinese children learn pinyin before characters and how pinyin (here written and on adults' computers/phones typed) is used as a substitute when dreaded character amnesia descends upon us.

It is also interesting which characters the girl did not know or was not confident enough to attempt to write. My 4 year-old daughter absolutely loves to shout “ xiū xiū xiū 羞羞羞" ("shame, shame, shame") at even the slightest example of impropriety; jiake, maidanglao, and hai are loan words; and the other missing characters 请 穿 显 帅 [VHM: see below for identifications and explanations] are not all that complex or rare. If pinyin is now a "base" of sorts for younger generations of Chinese people, it does raise the question of how much longer and in what situations will future generations want to use characters.

The last time I wrote about a similar use of Pinyin amidst characters by a Chinese youngster, there were some doubting Thomases: "Character amnesia and the emergence of digraphia" (9/25/13).

Whether or not that instance was authentic, there can be little doubt that the current example is genuine, and that it attests to the natural reliance of students upon Pinyin when they cannot recall various characters. Furthermore, nobody makes a big deal over it, and nobody laments that the poor little girl can't write all of the characters that she replaced with Pinyin. Quite the contrary, everybody seems to be rejoicing over the cleverness and cuteness of her essay. At most, some of the reports simply state casually that, when the little girl encountered characters that she couldn't write, she used Pinyin instead.

In the present instance of a child's intermixing of Pinyin and characters, we know exactly who she is and under what circumstances the writing occurred. Since her diary entry about the visit of the Chinese leader, Xi Jinping, to her school on November 1, 2014 has become an event of national interest involving the president of the country, it could hardly have been fabricated. From the little girl's diary entry, we also know the name of one other adult besides Xi Jinping who was present, while news reports tell us the name of the school, the names of the little girl's classmates, and so forth. The diary entry also tells us the names of local places where the action took place.

The writing certainly looks like that of a child. For example, she finds it hard to form yéyé 爷爷 ("grandpa") in a well-proportioned fashion, and jiù 就 ("then"), which she writes a couple of times, comes out looking more like jīng 京 ("capital") and yóu 尤 ("especially") than a single character.

According to the news reports that I have seen (here and here), the little girl's name is Zōu Ruìníng 邹 睿宁 and she will be 8 years old in a few months. The original reports are from the Hǎixiá dūshì bào 海峽都市報 (Strait City News) and Dōngnán wǎng 東南網 (Southeast Network) of Fujian province.

Below is a transcription and translation of the diary entry written by Zōu Ruìníng. An empty line has been added between paragraphs to make the divisions stand out more. Words written in Pinyin in the original are transcribed and translated in red. Note that the text breaks off in mid-sentence, which is where I end it, although some of the published versions complete it in a rather odd way: dàole “Xí dàdà” ne! 到了“习大大”呢!

PINYIN

2014 XX 11 Yuè 1 rì Xīngqíliù qíng

Jīntiān, tīng shuō Xí yéyé yào láile!

Wǒ xīn xiǎng: “Wǒ yào qǐng Xí yéyé chī Màidāng-

láo!"

Xiàwǔ, wǒ chuān shàng yīfu jiù qù

Jūnmén shèqū le! Wǒmen zhèng wán de hāi,

Lín Dān nǎinai wǎnzhe Xí yéyé de shǒu

jìnláile. Lín Dān nǎinai shuō: “Nǐmen kàn shuí

láile?” “Xí yéyé! Xí yéyé!” wǒmen yíng

guòqù jiào dào.

Xí yéyé chuānzhe jiákè shān, xiǎndé

hěn shuàiqì! Tā yī fù hàixiū de yàng-

zǐ, yǎnjīng dàdà de! Gètóu gāogāo de ne!

Tā qīnqiè de wèn wǒmen jiā zài nǎlǐ? Wǒ huí

dá: Zhúlín jìng. Tā cái wèn liǎng jù jiù zǒule,

Tài hàixiū le ba!

Wǒ jīntiān hěn kāixīn, yīnwèi jiàn

ORIGINAL DIARY ENTRY

2014XX 11月1日 星期六 晴

今天,听说习爷爷要来了!

我心想: “我要qǐng习爷爷吃Màidāng-

láo!"

下午, 我chuān上衣服就去

军门shè区了! 我们正玩的hāi,

林丹奶奶wǎn着习爷爷的手

进来了! 林丹奶奶说: “你们看谁

来了?” “习爷爷! 习爷爷!" 我们yíng迎

过去叫道。

习爷爷穿着jiákè衫xiǎn得

很shuài气! 他一fùhàixiū的 样

子, 眼睛大大的! Gè头高高的呢!

他亲切地问我们家在哪里? 我回

答: 竹林jìng! 他才问两句就走了,

太hàixiū了吧!

我今天很开心,因为见

TRANSLATION

November 1, 2014 Saturday Clear

Today we heard that Grandpa Xi was coming!

I thought to myself, "I want to invite Grandpa Xi to eat at McDon-

alds!"

In the afternoon, I put on my clothes and went

to the Military Gate Community! Just when we were playing merrily,

Grandma Lin Dan, leading Grandpa Xi by the hand,

walked in. Grandma Lin Dan said, "All of you look who

has come?" "Grandpa Xi! Grandpa Xi!" we

called out as we went over to welcome him.

Grandpa Xi was wearing a jacket that looked

very handsome! He had a shy appear-

ance, and big eyes! And he was very tall in size!

He kindly asked us where we lived. I re-

plied, "In the Bamboo Grove area. Whereupon he asked a couple of questions and left.

He's too shy!

Today I was very happy because I got to meet

Notes:

XX. Right at the very beginning, it seems that the girl was unable to write such a simple word as nián 年 ("year"), which is obligatory in children's diaries in this position.

Màidāngláo 麦当劳 (<"McDonald's")

chuān 穿 ("put on; wear") It's interesting that she gets this one right later on in the entry, though not without some smudging.

shèqū 社区 ("community")

hāi 嗨 (<"high") This does not imply that the children were playing around "high" on drugs. It merely means that they were having a great time, really enjoying themselves. There is an amazing and very popular song titled simply "High ge / High歌" ("High song"). If you listen to and watch through the whole video, you'll get a sense of the natural craze for English among young people in China.

wǎn 挽 ("pull; draw; lead by the hand")

yíng 迎 ("welcome; meet; greet; move towards")

jiákè 夹克 (< "jacket"), here joined with the Chinese word for "shirt" (shān 衫)

xiǎn 显 ("appear"), deceptively hard to write, she misses it twice (see below); it is much harder to write in the traditional form, 顯

shuài 帅 ("smart [looking]; handsome")

hàixiū 害羞 ("shy; bashful")

gè 个 ("self; individual"), here part of the word gètóu 个头 ("stature; body size")

jìng 境 ("territory; area; border")

hàixiū 害羞 ("shy; bashful")

The sentence that is getting the most traffic is this one:

Tài hàixiū le ba!

太hàixiū了吧!

[He's] too shy!

As I said above, nobody is making a fuss over the fact that Zōu Ruìníng couldn't write the key word of this sentence in characters. It is quoted all over the place, but in characters, yet I haven't seen anyone commenting on the fact that the most important word was written in Pinyin. They just naturally transcribe the Pinyin in characters without making any remark about the Pinyin, derogatory or otherwise. The use of Pinyin simply was not noteworthy. It's a natural phenomenon in elementary school education, just as the use of English is widespread in youth culture.

Here are some relevant posts for additional background:

- "Dumpling ingredients and character amnesia" (10/18/2014)

- "Biscriptal juxtaposition in Chinese" (8/17/14)

- "Biscriptal juxtaposition in Chinese, part 2" (10/15/14)

[Thanks to Fangyi Cheng and Rebecca Fu]

Richard W said,

November 9, 2014 @ 11:27 pm

I observed another form of substitution at a restaurant yesterday. We ordered 蛋餅 (dànbǐng: egg pancakes) for breakfast at a Taiwanese restaurant in Melbourne's Box Hill Chinatown. I looked at the docket to see what the waitress had written, and was amused to see 旦并, which isn't a word at all, as far as I know. She might have been able to write 蛋餅 but she used a nonsense word that is faster to write, and can be read as dànbìng, which is similar enough to dànbǐng to be understood in context. Maybe there's nothing unusual about that. I haven't paid much attention to dockets before.

http://www.cjkware.com/search?query=%E8%9B%8B%E9%A4%85&option=

dom said,

November 10, 2014 @ 12:26 am

Richard – waitstaff shorthand is not unusual at all. People will substitute 反 for 飯, C for 絲 (in Cantonese), etc.

Elessorn said,

November 10, 2014 @ 12:44 am

If pinyin is now a "base" of sorts for younger generations of Chinese people, it does raise the question of how much longer and in what situations will future generations want to use characters.

What are your thoughts on this thought? It makes perfect sense, as you say, that the child's use of substitute pinyin would be totally unremarkable– everyone would immediately understand the motivation and circumstances underlying it. And I completely sympathize with your (admirably patient) frustration over the doubting Thomases, with their perhaps wishful blindness to the complexity of Chinese orthography today. Yet it does seem a shame how very familiar this concluding thought is.

Maybe alphabetic efficiency does destine a Sinolatinate digraphy for the Turkish solution. Or maybe the Latin alphabet will come to function like Chinese kana. Who knows? The Chinese peoples will decide. For the time being it's hard for me to understand why so many think there's a good chance the choice is an obvious one. At the very least the apparent absence of a moral panic in this case over the child's pinyin usage offers a data point against it.

David Moser said,

November 10, 2014 @ 2:54 am

Great post! I, too, found it interesting that the newspaper articles all printed the girl's letter with the original Pinyin retained, without commenting on the different orthographies. Indeed, this sort of Pinyin usage is very common. I hope her teachers encourage her to continue this practice. How sad if she had been discouraged from even writing the essay to begin with just because she couldn't write all the characters. And I must admit that even though I've studied Chinese almost 30 years, I myself had to struggle to remember how to write the character 羞.

flow said,

November 10, 2014 @ 3:52 am

@Richard W nothing specifically Chinese about this—waiters and bar tenders have to write down the same small set of words day in day out, and they all resort to abbreviations the world over. in the west that tends to come out as letters, figures, squiggles no uninitiated can readily decipher, and it's no different in Taiwan where the kitchen people without effort read out the 旦並 and 左宗几.

JQ said,

November 10, 2014 @ 4:07 am

@Richard W

There is nothing unusual about restauranteurs and waiter/resses using abbreviated forms of characters to write orders. It's a bit like a code and in fact, 旦并 is probably the standard way of writing this when taking customer orders.

I don't think anyone would blame an 8-year-old for not knowing how to write certain characters. Would people be commenting on the spelling errors of a similar English-speaking student? If she was 13 or 14 then things might be different – except for 嗨, they are all relatively common characters that I knew how to write after starting high school (and I didn't go to school in a Chinese country).

Akito said,

November 10, 2014 @ 4:32 am

"I hope her teachers encourage her to continue this practice."

Wanting to write something, pinyin or not, is a good thing, but eventually her teachers will encourage her to graduate this practice if they see it as their job to help her grow to be a mature, literate member of society.

Jason said,

November 10, 2014 @ 5:00 am

@Elessorn

"At the very least the apparent absence of a moral panic in this case over the child's pinyin usage offers a data point against it."

Give it time… moral panics only occur when people perceive some kind of threat.

leoboiko said,

November 10, 2014 @ 5:27 am

Or they'll just use both, like the Japanese do with kana. They developed phonography like a thousand years ago, and the people are still happily using morphographic Chinese characters in daily life.

Roger Depledge said,

November 10, 2014 @ 6:02 am

It is interesting that you believe that "an event involving the president of the country… could hardly have been fabricated". I would have thought precisely the reverse. Perhaps the incentives of schoolteachers and PR people in China are different. Suppose the little girl had written "[He's] too ugly!"

Victor Mair said,

November 10, 2014 @ 7:42 am

@Roger Depledge

"I would have thought precisely the reverse."

So you think that the diary entry is phony? That the little girl did not write it herself? That somebody faked the childish writing and the insertion of Pinyin?

@Richard W and the many people who replied to his comment:

The simplified substitutions used by Chinese wait staff tend to be phonetic in nature and illustrate the principle of phoneticization. The same thing has happened many times in history: Egyptian demotic, Akkadian cuneiform, the Phoenician consonantary, the Greek alphabet, Japanese kana, Korean hangul, nüshu (women's script [in the southern part of Hunan Province])…. It doesn't always happen in one fell swoop, but is the incremental, natural consequence of people in a hurry wanting to write things more or less the way they sound, instead of following some arcane rules and traditional practices that push them in the direction of more complicated writing.

Rodger C said,

November 10, 2014 @ 7:51 am

@Victor Mair: I didn't read Roger Depledge's remark as doubting the authenticity of the entry, only that he was puzzled by the logic of your remark, as am I.

Victor Mair said,

November 10, 2014 @ 9:42 am

@Rodger C

The logic of my remark is that, however much others may have doubted the authenticity of previous specimens of children mixing Pinyin and characters, this instance is so well documented and of such a high profile that it is hard to believe that it would have been fabricated. I don't see why that is so hard to understand.

Ned Danison said,

November 10, 2014 @ 12:33 pm

Children in Taiwan use 注音符号/phonetic symbols for characters they can't write, and children in China use pinyin. We don't see the former as a portent of future generations switching to phonetic writing, so I don't think we can take the latter as a portent either. This is in response to Mr. Rutherford's comment. I understand this was not Professor Mair's point.

Jeff W said,

November 10, 2014 @ 1:27 pm

And that means what?

(I’m not doubting that it’s meaningful. I’m trying to figure out what meaning you’re ascribing to the “not noteworthiness” and, rather than guess, I figured I’d ask.)

markonsea said,

November 10, 2014 @ 2:17 pm

No one seems to have taken note of the obvious: that the reason phonetic writing has not taken off and is unlikely to take off in Chinese and Japanese is that the wealth of homophones miltates against it.

Waiting and kitchen staff are daling with a very limited subset of the overall vocabulary, and a hint will usually be enough.

Victor Mair said,

November 10, 2014 @ 2:53 pm

@Jeff W

I said it in so many different ways in the original post; you ought to be able to figure it out easily.

http://www.thefreedictionary.com/noteworthy

@markonsea

If there were too many homophones in Chinese and Japanese, it would be difficult for people to hold a conversation in these languages. As I've said so often, nobody ever spoke a hanzi / kanji / hanja (except in cartoon bubbles).

BTW, I published a journal of Romanized Mandarin for about ten years, and people who were fluent in Mandarin and familiar with Pinyin had no trouble understanding it. My wife wrote her childhood memoirs in Pinyin, and many readers have found them to be deeply moving (without a single character in them). Within a few months, I will announce a Pinyin literature contest in her memory, and I'm confident that there will be a lot of worthy submissions, and later — when the winners are published — plenty of happy readers.

John Emerson said,

November 10, 2014 @ 6:05 pm

I used to know a Japanese-American science PhD who went to HS in Japan and college and grad school in the US. He said that in Japan the higher proportion kanji you use the higher your social class is thought to be. Good calligraphy also counts.

As I understand this was changing (he was ~35 in 1980). His kanji were not so good because he majored in sciences.

John Emerson said,

November 10, 2014 @ 6:11 pm

When I was in Taiwan in 1983 I saw many cases of latin alphabet / english language abbreviations for Chinese words. The post office used "5F" for wulou, fifth floor. One hospital used W1 on a schedule to mean xinqi 1, Monday. And people read TAXI as the Chinese word.

Eidolon said,

November 10, 2014 @ 8:49 pm

@markonsea Homophones are not a big issue, as context is normally available to distinguish between them. The bigger issue is linguistic unity and cultural pride. The Sinitic languages are mutually unintelligible in pinyin, but not in written Putonghua, which is what is taught in Chinese schools. Even though Cantonese, Hakka, Hokkienese, etc. pronounce written Putonghua sufficiently differently so as to be mutually unintelligible when speaking/pinyin writing, when writing Putonghua with characters, they ARE intelligible. While there is the argument that it is easier to encourage linguistic unity when there is only one way to pronounce Putonghua, the fact of cultural regionalism in China prevents the PRC government from simply forcing everyone to speak the national standard, so they compromise by ingraining the same written standard first.

Cultural pride is an even bigger obstacle. With all the bad reputation surrounding copycat culture in modern China, I'd think the last move the Chinese want to make is to adopt a Western script to write their own language.

Michael Watts said,

November 10, 2014 @ 9:12 pm

@Jeff W:

The reason he's calling out the use of pinyin as not being noteworthy is that he's worried about moral panics over the use of pinyin — to him, it's worth noting that this diary entry isn't kicking one off. Many Chinese, especially the more educated Chinese, are attached to the characters and advance some truly awful arguments for why they're necessary.

The cultural pride issue could be fairly easily dealt with by use of zhuyin instead of pinyin; a latin-based alphabet has nothing in particular to offer over another alphabet. Sadly, I suspect that China hates Taiwan even more than it hates the west.

Eidolon said,

November 10, 2014 @ 9:26 pm

@Michael Watts I don't think they hate the Taiwanese, or the West for that matter. However, and I ought to have written this in my previous comment, cultural pride with regards to hanzi extends beyond the oppositional narrative of East vs. West. It is also a source of Chinese 'uniqueness' and their feeling of connection to the past. While such existential emotions are capable of being overwritten in times of great practical need, such historical moments are rare and triggered by severe crisis. The mood at the turn of the 20th century was such that replacing hanzi altogether was considered by not a few Chinese policy makers and intellectuals to be a positive, even necessary, move. Today, however, with China's economic rise and surging nationalism, whatever voices remain for the adoption of pinyin/zhuyin over hanzi is liable to sound unpersuasive.

Victor Mair said,

November 10, 2014 @ 9:34 pm

@Eidolon

Well put (both of your comments).

That's why I always speak of "emerging digraphia". Whatever happens with the characters vis-à-vis Pinyin, it will come about naturally and gradually. I doubt seriously that anyone will attempt an Ataturk style script reform in China. If Mao couldn't do it (at first he wanted a radical change of script, but then gave up the idea, which is one of the reasons John DeFrancis became disenchanted with him), probably nobody could. Even though Xi Jinping is amassing great power, he certainly doesn't seem like the type of person to attempt a radical reform of the script, especially not when he has lately been touting the classics!

So, every time the discussion of Pinyin vs. the characters comes up on Language Log, we don't have to think of it as one or the other, i.e., as if they were mutually exclusive. Kana and kanji, the one syllabic and the other morphosyllabic, have peacefully coexisted for well over a thousand years. There's no reason why Pinyin and hanzi cannot likewise coexist, each fulfilling the roles for which they are best suited. Hanzi continue to function as China's main script, but Pinyin is already assuming the useful role of an auxiliary script, which is what people like Zhou Youguang wanted it to be. It is used for inputting, indexing, braille, semaphore, sorting, ordering, identification at archeological sites, in advertisements, in science, in the military, in education (learning to read), and, not least, as a handy way to write down the sound of a word when one doesn't know how to write it in characters, as well as in many other capacities. No potentate has either ordered or forbidden these things to happen. They are happening because people are finding Pinyin useful for particular applications, which I consider a healthy situation.

Victor Mair said,

November 10, 2014 @ 9:35 pm

@Michael Watts

"…he's worried about moral panics over the use of pinyin…."

Not I! If there's a moral panic, so be it. I really don't care. It's totally up to the Chinese if they become upset about little children using Pinyin to write down the sounds of words for which they have forgotten (or never learned) the characters. In the present case, I merely observed what has happened: nobody got upset or excited about it.

As for the PRC hating Taiwan more than they hate the West, I'm sure that's not the case. After all, they're tóngbāo 同胞 ("compatriots"), especially with Ma Ying-jeou at the helm in Taiwan — and they both speak Mandarin as their national language.

Eric P Smith said,

November 10, 2014 @ 9:36 pm

As someone who knows no Chinese, I am just lost in admiration that any child can learn to write in characters at all.

Richard W said,

November 10, 2014 @ 11:57 pm

Thanks to all who informed me how ordinary it is for wait staff to use those simpler forms, and thanks especially to Victor Mair for providing that broader perspective on the practice.

Jeff W said,

November 11, 2014 @ 5:35 am

@Michael Watts

Thank you for your response.

My own (very naive) take on this issue is that Pinyin in an elementary school setting in China is used as a “stepping stone” to standard written Mandarin and it would be completely expected and uncontroversial if little kids substituted pinyin for characters they didn’t know, were unsure of, or forgot. (Who knows? They might even be encouraged by their teachers to do so.)

So was Victor Mair posting about this high-profile example as being consistent with that or maybe something else? I couldn’t tell. Your response to me was a lot more helpful than his was about it being “obvious.”

@Victor Mair

“I merely observed what has happened: nobody got upset or excited about it.”

I was trying to ascertain whether the post was “mere observation” or something in addition to that. If you’re saying no one was “making a big fuss” or “lamenting” (or “got upset or excited”) over a child’s use of pinyin in an elementary school setting, that can give rise to the inference that someone somewhere was expected to do just those things and hasn’t—I couldn’t tell if such an inference was warranted or not (and, if it was warranted, why, in this instance having to do with an elementary school kid, given my view of pinyin above).

But my point of view doesn’t matter, which is why, initially, I simply asked what meaning you were ascribing to your observation. You might be ascribing no meaning to it—you’re just “merely observing”—but if you are, then I guess I can’t be faulted for not finding the meaning “obvious” and asking about it.

Guy said,

November 11, 2014 @ 9:41 am

As someone who was taught Chinese in a Taiwanese school, I've always found it curious that pinyin has been preferred over zhuyin in the mainland.

It has all the advantages of pinyin – accuracy, easy to type with on electronic devices and an orderly system to look up words in a dictionary.

More importantly, aesthetically, mixed zhuyin/hanzi looks much less jarring than pinyin/hanzi mixed script. Similar to how kana/kanji work together nicely in Japan (or hangul/hanja in Korea).

Its quite common for Taiwanese kids who aren't old enough to write properly yet to use zhuyin when they don't know how to write a character. Despite its ubiquitousness in Taiwan, no one would seriously consider that zhuyin could ever be functionally able to compete with or replace hanzi.

I wonder if it is the association with the ROC or maybe it looks just a bit too much like Japanese kana for the mainland Chinese to be comfortable?

Victor Mair said,

November 11, 2014 @ 11:04 am

@Jeff W

You're splitting hairs and being tortuously convoluted to boot. Furthermore, you twice quote me as using the word "obvious". Please show me where I did that. "Obvious" is a word that I try, as much as possible, to avoid. If I did use that word, please forgive me, but if I didn't….

@Michael Watts

This morning, my class and I were trying to figure out how there could be "moral panics over the use of pinyin…" and what that might mean.

Bob Davis said,

November 11, 2014 @ 12:38 pm

As one who knows no Chinese (ok-2 words: ye-ye and wai-gon) I was amazed watching kids in my high school taking Chinese AP test on a computer. They were typing in pinyin (I assume?) and the symbols would appear. Then a column of three or four symbols might appear and the students would click on one (right, write, rite, wright?) I struggled to learn and write one word: leaf (ye?) R U sure that computer use will not have N impact on how we rite N the fuchur?

Chris McG said,

November 11, 2014 @ 7:07 pm

@ Jeff W

Thanks for asking about that, I wasn't able to "figure it out easily" either.

Elessorn said,

November 11, 2014 @ 8:35 pm

This morning, my class and I were trying to figure out how there could be "moral panics over the use of pinyin…" and what that might mean.

That's the whole point, in a way. Or at least my point. There shouldn't be. But many Westerners do see characters as precisely the sort of historically-contingent material-culture mere habit that is most likely to induce a moral panic at the moment of its (inevitable) passing. After all, characters are imagined to show the same gap between invested sentiment and comparative practical utility that we recognize at the root of such panics in the US (e.g. over cursive writing)–as one of those things vulnerable to a sneaking replacement, belatedly and tiresomely to be lamented when its end is sure.

If your students realize characters are nothing like the Chinese version of Fraktur typeface, not the sort of thing that is likely to be unconsciously selected against in the wild for efficiency, until one day we wake to find them endangered, then good on them. Characters are hardly the only item of non-Western culture that would benefit in understanding immensely from our hesitation to apply categories of utility that feel, but are not, natural.

JIm Manheim said,

November 11, 2014 @ 10:04 pm

A comment by a friend who taught in China for awhile. Never encountered this idea and wondered whether there's something to it. <<. <>

Jim Manheim said,

November 11, 2014 @ 10:06 pm

. <<I occasionally saw kids annotating their Chinese homework with Pinyin letters, yes. But more significantly, the whole process of learning to write by ideograph changes the way people learn. Since there is very little phonetic relationship between a character's appearance and its pronunciation, Chinese kids who are learning to write can't sound words out for themselves; they have to wait until they are told by an authority (a teacher or a dictionary) what a character means. I think this molds their learning style for life.

Akito said,

November 12, 2014 @ 3:00 am

I think we should bear in mind that pinyin and kana have quite different functions. In Japanese, most content words and stems of conjugated words are written in kanji (or katakana if the words are borrowed from languages other than Chinese, but let's put that aside for the moment) and function words and affixes in hiragana. That is to say, kanji and kana have different grammatical roles to play. This division of labor applied to hanja (kanji) and hangeul in Korean when the language used hanja (kanji) more extensively than now. Mandarin, on the other hand, has little inflexion and only a small number of affixes. Pinyin are therefore best used as ruby, pronunciation guide for L2/L3 learners, and temporary replacements for forgotten or complicated characters. The notion that it could play the same or similar role as kana is a little too far-fetched.

As for inputting, I personally find pinyin typing the easiest, but I'm sure zhuyin (bopomofo) inputting is just as easy for people familiar with it, just as Korean speakers generally find typing hangeul easy and natural to them.

Jeff W said,

November 12, 2014 @ 6:09 pm

@Victor Mair

You’re right about the word “obvious”—I was substituting that word for “ought to figure that out easily” in your initial reply to me. I apologize.

@Chris McG

Thank you—I appreciate your comment. I am glad I’m not alone.

hwu said,

November 12, 2014 @ 8:50 pm

As someone from mainland China, I can say confidently that using pinyin is encouraged by most primary school teachers (and by primary school teachers only), so there is no moral panic. however, use homophone for forgotten character is much more socially acceptable among adolescents, and the shift from pinyin to homophone usually happens during high school.

An evidence is that while wrongly used homophones (e.g. 鸡旦/鸡蛋) are common on small restaurants' menus, they never appear in pinyin form, and waiters seldomly use pinyin to write orders.