Coined Chinese characters: The 24 solar terms, part 2

« previous post | next post »

The calendrical system used for defining the dates of traditional Chinese festivals such as ‘Chinese New Year’ (The first day of the first lunar month, now called 'Spring Festival’ Chun jie 春節 in the PRC), the mid-autumn festival 中秋 (full moon of the 8th lunar month) and so on is the last of the many versions of the Chinese luni-solar calendar that were adopted by successive imperial governments until the fall of the empire in 1911. It is in fact the system adopted by the Qing dynasty in 1644.

Christopher Cullen’s book Heavenly Numbers: Astronomy and Authority in Early Imperial China (Oxford, 2017) gives a detailed account of the successive systems of mathematical astronomy that were used by Chinese astronomical officials in early imperial times to produce the annual luni-solar calendars that were promulgated by imperial authority. The following explanations are taken from Cullen’s book.

Cullen, pages 33-39 “'Completing the year': running a luni-solar calendar in the second century BCE” explains how a luni-solar calendar was run so as to solve the problem of keeping in step with the moon’s cycle of phases, and also with the annual solar cycle that underlies the seasons of the year. As he points out, the basic regularities on which such calendars were based were explained in the Huai nan zi 淮南子 book, which was offered to the throne in 139 BC.

All versions of luni-solar calendars used in China tried to reconcile two different cycles:

1. The cycle of the seasons; in China this was taken to be the mean interval between successive winter solstices, for which a modern value is 365.243 days, and was the basis of the year.

2. The synodic month, which defines the mean interval at which the phases of the moon recur. The modern value is 29.53059 days.

Whereas purely solar calendars like the Julian or Gregorian calendars keep the year in step with the seasons by inserting extra days at regular intervals, a luni-solar calendar needs to use intercalary months. A normal year will contain 12 lunar months, but that will give a year 11 days shorter than the sun’s cycle, so an extra ‘intercalary month’ 閏月 will need to be inserted about every three years, giving a 13-month year. Since to a good approximation 19 tropical years add up to the same number of days as 235 synodic months, the basic rule explained in Huai nan zi and followed in succeeding centuries was that since

235 = 12*19 +7

all that was needed was to insert 7 intercalary months over 19 years.

But exactly when should intercalary months be inserted? For an explanation of that, we may turn to the discussion in Cullen 164-165 “Month numbers and intercalation”.

Here we see that far from the 24 jie qi 節氣 being irrelevant to the luni-solar calendar, they are essential to its smooth operation, since without them we would not know where intercalary months should be placed.

The system works like this. Imagine that all the qi are numbered, beginning with Winter Solstice dong zhi 冬至 as number 1,Lesser Cold xiao has 小 寒 as number 2, all the way up to number 23 'Lesser Snow' xiao xue 小 雪, and number 24 'Great Snow' da xue 大雪. We then designate all the odd-numbered items in the list as ‘Medial qi’ zhong qi 中氣 and (a little confusingly) all the even-numbered items as ’Nodal qi’ jie qi 節氣. Each month is then associated with a Nodal qi and a Medial qi. Thus lunar month number 1, the first month of the civil year, has Nodal qi number 4 'Establishment of Spring' li chun 立春, and Medial qi number 5 'Rain Waters' yu shui 雨水. Lunar month 2 has Nodal qi number 6 'Awakened Insects' jing che, 驚蟄 and Medial qi number 7 'Spring Equinox' chun fen 春分, and so on. For most of Chinese history, the 24 jie qi were defined as equal divisions of the time elapsed from one winter solstice to the next. Thus for example, if we are operating with a tropical year length of 365 1/4 days (as defined in the astronomical system adopted in 85 CE) days, each jie qi will be (365 1/4)/24 = 15 7/32 days long. So two Medial qi will be separated by an interval of 30 7/16 days.

Since lunar months must follow the cycle of lunar phases as closely as possible, while having a whole number of days, their lengths will in most cases alternate between 29 and 30 days. As a result of this, it is just possible to have a Medial qi at the end of one month, and for the next Medial qi not to fall in the following month, but to be placed at the beginning of the month after next. As a result, the intervening month will have no Medial qi. Such months are designated as ‘intercalary months' run yue 閏月 and are given the same number as the preceding month, prefaced by run 閏, as in run jiu yue 閏九月 ‘intercalary ninth month’ if it follows the ninth month.

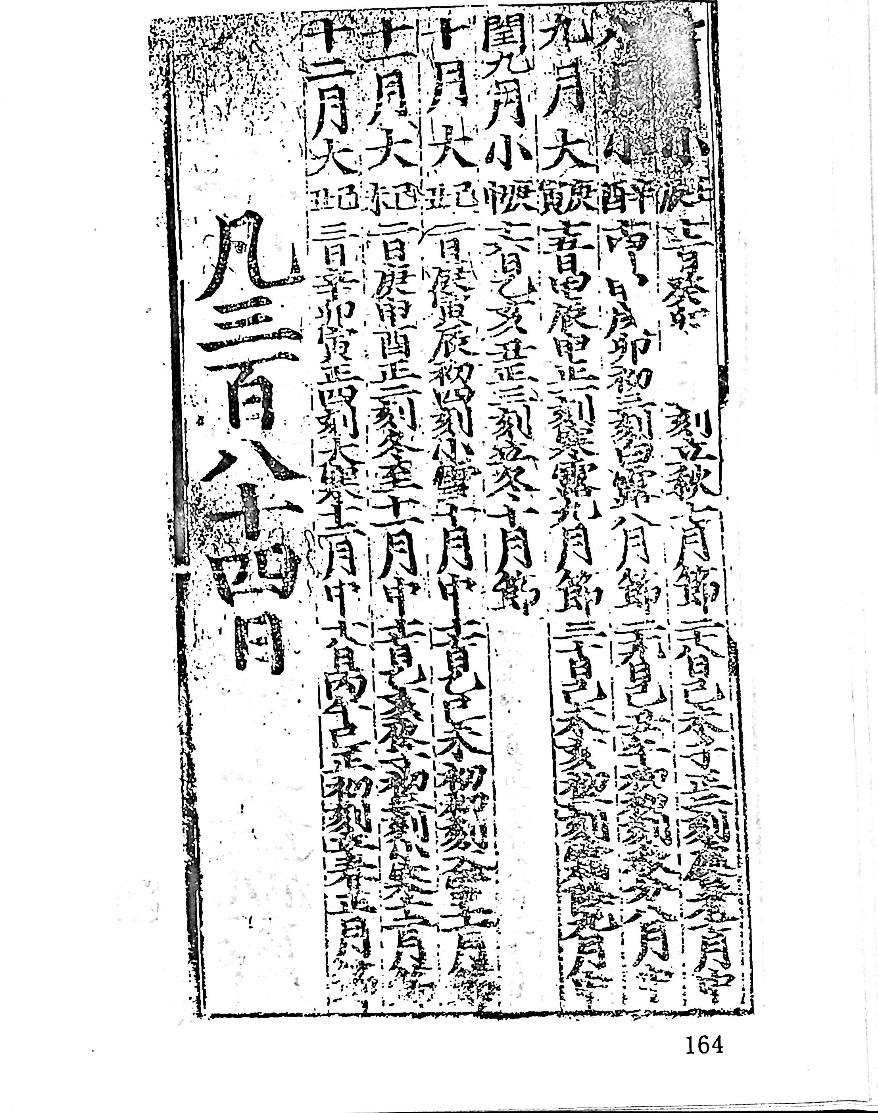

The following page from a Ming dynasty calendar for the third year of the Jing tai 景泰 reign period (1452-3) shows precisely this situation. The Medial qi for the ninth month falls on the last day of that month (day 30), and the Medial qi for the tenth month falls on the second day of that month. In between is the intercalary ninth month, with no Medial qi. As usual, the year ends with the month numbered 12, but in fact the year contains 13 lunar months, and as marked in large characters on the left, it is made up of a total 384 days.

(Image from Anon. (2007). Guo jia tu shu guan cang

Ming dai da tong li ri hui bian 國家圖書館藏明代大統曆日彙編

(Collected Ming dynasty Da tong li calendars from the National Library).

Beijing, Beijing tu shu guan chu ban she 北京圖書館出版社, vol 1. )

By the way, in case anybody suggests that the interval between winter solstices on page 34 should be 365.242 days rather than the 365.243 days Cullen gives, please see the study by Meeus cited in footnote (40) where the latter figure is given for the mean interval between December (i.e., winter) solstices. The former figure is the mean interval between March (spring) equinoxes. In both cases Cullen gives values correct to three decimal places, where Meeus gives values to 6 places.

———

Christopher Cullen is Director Emeritus of the Needham Research Institute at the University of Cambridge and is General Editor of the Science and Civilisation in China series, succeeding Joseph Needham.

Selected readings

wgj said,

August 6, 2025 @ 1:51 pm

The current version of the Chinese calendar is not the Timely-Constitution-Calendar 時憲歷 of 1644, but the Purple-Gold-Calendar 紫金歷 of 1929. While the latter is only a minor revision of the former, it is a revision nonetheless. One substantive difference being that modern astronomical methods have replaced four century old astronomy.

This is important because the Chinese calendar is still an astronomical calendar that aligns itself to the movement of celestial bodies – unlike the Gregorian calendar, which is purely algorithmic (and only stays true to the astronomical cycles through irregular leap seconds). That means, while you can tell your computer to show you the Gregorian calendar for the year 9025, you can't get an official Chinese calendar for the year 2035 right now, because the movements of the sun and the moon aren't strictly regular due to the solar system not being a closed system. So the Purple-Gold-Mountain Observatory in Nanjing (a great place to visit BTW), as the national observatory of the PRC (and before that the national observatory of the ROC, and after whom the current calendar is named), has to keep constant track of the sun and the moon, and calculate the calendar a few years ahead only in order to stay precise.

Jonathan Smith said,

August 6, 2025 @ 1:52 pm

Hmm, I now realize that Diana Shuheng Zhang's line from the first post ("the 24 solar terms 节气 (jieqi) in the traditional Chinese lunar calendar for agricultural purposes") might not mean to say that the 24 terms per se comprise a lunar calendar for agricultural purposes — in which case the language should indeed be adjusted to refer to a "solar calendar" for (or at least related to) agriculture purposes — but simply mean to say that the 24 terms are part are part of a larger traditional Chinese lunar calendar for agricultural purposes, in which case the language should instead be adjusted to refer to a "lunisolar calendar" and with the agriculture angle removed or qualified. My bad.

Point re: "jieqi" was simply that, as Cullen says, "for most of Chinese history, [the jieqi] were defined as equal divisions of the time elapsed from one winter solstice to the next", i.e., they comprise a solar calendar.

wgj said,

August 7, 2025 @ 2:42 am

The notion that the Spring Festival / Chinese New Year is celebrated on the first day of the first lunar month is also not unreservedly correct. It is commonly believed (among the few experts who research this topic) that in ancient times (say, until the Han Dynasty), the Spring Festival and the New Year were both celebrated on the day of the solar term Arrival of Spring, which marks the first day of the (purely solar) Stem-Branch-Calendar. Throughout later dynasties, the main day of celebration would switch back and forth between the solar and the lunar new year (for complex and fascinating reasons), until in recent times (say, since the Ming Dynasty), it would settle on the lunar new year.

This creates a conflict on the important question, when does the year start and end for a particular zodiac animal? On one hand, people generally accept that the year of a given animal starts and ends with the popular lunisolar calendar year (in fact, most aren't even aware there's an alternative); on the other hand, the rules for the Stem-Branch-Calendar hasn't changed – its year still starts on the Arrival of Spring, and the "eight characters" denoting one's year, month, day, and hour of birth is still strictly derived from the Stem-Branch-Calendar (the lunisolar calendar doesn't have an alternative version of that).

So a child born on (Gregorian) 1 February 2025 is commonly understood to be born in a year of the snake, but their eight characters would still start with jiachen (1-5) instead of yisi (2-6), marking them as a dragon.

Personally, I'd love to see the Arrival of Spring returning to its rightful place as the main day of celebration. This would also have the added benefit of having a fairly stable date for the Chinese New Year. (I'm involved with annual planning and reporting at the beginning of the year, and our work schedule for this task has to be re-negotiated every year because the CNY keeps shifting around.)

Chas Belov said,

August 13, 2025 @ 10:30 pm

I encountered Lim Giong's album Insects Awaken long before I encountered "Insects Awaken" on my Outlook calendar. When I saw it on my calendar – I had Outlook set to show all holidays it knew about – I asked a Chinese co-worker about it and he explained to me about the 24 periods.

It's an enjoyable album by the way.