A brief literary linguistic analysis of the Gettysburg Address

« previous post | next post »

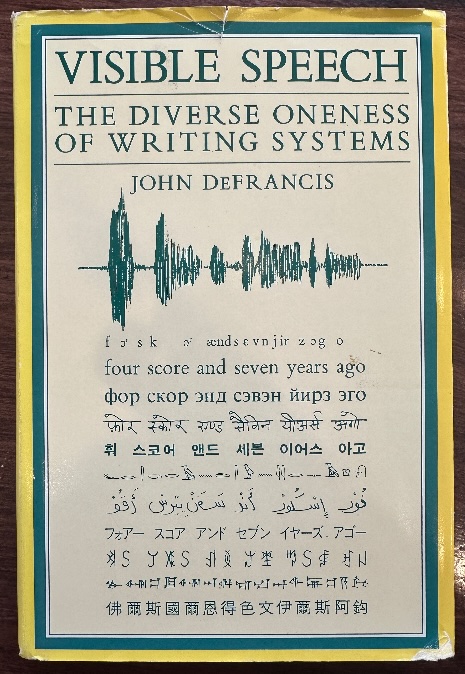

Above is the cover of John DeFrancis's magnum opus, Visible Speech: The Diverse Oneness of Writing (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 1989). It has a stunning illustration consisting of the phonetic representation of the first six words of Lincoln's Gettysburg Address transcribed as follows: acoustic wave graph of the voice of William S.-Y. Wang, IPA, roman letters, Cyrillic, devanagari, hangul, Egyptian hieroglyphics, Arabic, katakana, Yi (Lolo, Nuosu, etc.), cuneiform, and sinographs (a fuller version of the cover illustration may be found on the frontispiece [facing the title page] and there is a generous explanation on pp. 248-251).

Why am I writing this post about the Gettysburg Address, and why did I begin this post that way, focusing on each phoneme of the address? Because I believe that this short oration was divinely inspired, and that the soon-to-be (six weeks later) assassinated President carefully chose every syllable and each sound and silent pause of what he said on that momentous occasion. He did not dash off the speech on a trundling train from Washington through Hanover Junction, Pennsylvania to Gettysburg. Two copies of the text were written in Lincoln's steady hand on a stable surface before delivery.

Before turning to the actual historical circumstances of the speech and its delivery, let us look at some of the key literary aspects and elocutionary attributes of the text:

The Gettysburg Address is notable for its use of powerful rhetorical devices like anaphora (repetition of words at the beginning of sentences), alliteration (repetition of consonant sounds), antithesis (contrasting ideas), allusion (references to other texts), and parallelism (similar sentence structures), all contributing to its concise and impactful delivery, emphasizing themes of sacrifice, democracy, and the ideal of equality.

Key literary aspects of the Gettysburg Address:

Anaphora:

The most prominent device, seen in phrases like "We cannot dedicate – we cannot consecrate – we cannot hallow this ground".

Alliteration:

"Four score and seven years ago" is a classic example, where the "f" sound is repeated.

Antithesis:

"The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here".

Allusion:

"conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal" references the Declaration of Independence.

Parallelism:

Using similar sentence structures to emphasize key ideas.

Concise Language:

The speech is remarkably short yet conveys profound meaning due to careful word choice.

How these aspects contribute to the speech:

Emotional Impact:

Repetition and powerful imagery create a sense of solemnity and reverence for the fallen soldiers.

Unity and Purpose:

By invoking shared ideals and history, Lincoln unites the audience in their commitment to the cause.

Persuasive Power:

The carefully crafted language reinforces the importance of the sacrifice made at Gettysburg and the need to continue fighting for the cause.

(Source: "Literary aspects of the Gettysburg Address" [AIO | [1/6/25])

The above is not an exhaustive account of the rhetorical aspects and literary virtues of the Gettysburg Address, but I trust that it is sufficient to vouch for the verbal and mental power that is concentrated in this concise text.

The raison d'être for this post is to answer the question I raised in "Machine translators vs. human translators" (1/7/25) about whether LLMs can ever do nuanced, sensitive literary translation. When I raised that question, I already felt that the answer was "no". Having completed this exercise, I'm all the more convinced that that will never happen.

In inviting President Lincoln to the ceremonies, David Wills, of the committee for the November 19 Consecration of the National Cemetery at Gettysburg, wrote, "It is the desire that, after the Oration, you, as Chief Executive of the nation, formally set apart these grounds to their sacred use by a few appropriate remarks."

On the train trip from Washington, D.C. to Gettysburg on November 18, Lincoln was accompanied by three members of his Cabinet, William Seward, John Usher, and Montgomery Blair, several foreign officials, his secretary John Nicolay, and his assistant secretary, John Hay. During the trip, Lincoln remarked to Hay that he felt weak; on the morning of November 19, Lincoln mentioned to Nicolay that he was dizzy. Hay noted during the speech that Lincoln's face had "a ghastly color" and that he was "sad, mournful, almost haggard". After the speech, when Lincoln boarded the 6:30pm train to return to Washington, D.C., he was feverish and weak with a severe headache. A protracted illness followed, which included a vesicular rash; it was diagnosed as a mild case of smallpox. It is highly likely that Lincoln was in the prodromal period of smallpox as he delivered the Gettysburg Address.

After arriving in Gettysburg, which had become filled with large crowds, Lincoln spent the night in Wills's house. A large crowd appeared at the house, singing and wanting Lincoln to make a speech. Lincoln met the crowd but did not have a speech prepared, and he returned inside after saying a few extemporaneous words. The crowd then continued to another house where Secretary of State William Seward delivered a speech. Later that night, Lincoln wrote and briefly met with Seward before going to bed at about midnight.

Surrounded by crowds, Lincoln delivered the Gettysburg Address around 3 PM. He was already at the site by noon, so was waiting there for three hours before making the speech.

The Gettysburg Address takes about 2-3 minutes to deliver. Edward Everett, renowned as the nation's finest orator, spoke for 2 hours before Lincoln. Everett was deeply impressed by Lincoln's concise speech and wrote to Lincoln noting "I should be glad if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes." (source)

Consisting of only ten sentences and 272 words, the impact of the Gettysburg Address was immediately and inversely overwhelming. Ultimately, a portion of its last sentence — "government of the people, by the people, for the people" — would even provide the foundation for the Three People's Principles (Sānmín Zhǔyì 三民主義) that formed the bedrock for the political philosophy of the Republic of China founded in 1912 by Sun Yat-sen (1866-1925) and technically still alive in Taiwan today.

Detail from Government. Mural by Elihu Vedder. Lobby to Main Reading Room,

Library of Congress Thomas Jefferson Building, Washington, D.C.

Main figure is seated atop a pedestal saying "GOVERNMENT" and holding

a tablet saying "A GOVERNMENT / OF THE PEOPLE /

BY THE PEOPLE / FOR THE PEOPLE".

Artist's signature is "ELIHU VEDDER / ROMA–1896".

This is a file from the Wikimedia Commons.

The power of this short speech far transcends the individual words of which it is composed.

Read, recite, remember:

The Gettysburg Address

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

November 19, 1863

On June 1, 1865, Senator Charles Sumner referred to the most famous speech ever given by President Abraham Lincoln. In his eulogy on the slain president, he called the Gettysburg Address a "monumental act." He said Lincoln was mistaken that "the world will little note, nor long remember what we say here." Rather, the Bostonian remarked, "The world noted at once what he said, and will never cease to remember it. The battle itself was less important than the speech."

There are five known copies of the speech in Lincoln's handwriting, each with a slightly different text, and named for the people who first received them: Nicolay, Hay, Everett, Bancroft and Bliss. Two copies apparently were written before delivering the speech, one of which probably was the reading copy. The remaining ones were produced months later for soldier benefit events. Despite widely-circulated stories to the contrary, the president did not dash off a copy aboard a train to Gettysburg. Lincoln carefully prepared his major speeches in advance; his steady, even script in every manuscript is consistent with a firm writing surface, not the notoriously bumpy Civil War-era trains. Additional versions of the speech appeared in newspapers of the era, feeding modern-day confusion about the authoritative text.

Here I present only the best known copy of the Gettysburg Address, the Bliss Copy — but I present it in the context it was written and distributed. For the other four known copies, see here.

Bliss Copy

Ever since Lincoln wrote it in 1864, this version has been the most often reproduced, notably on the walls of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington. It is named after Colonel Alexander Bliss, stepson of historian George Bancroft. Bancroft asked President Lincoln for a copy to use as a fundraiser for soldiers (see "Bancroft Copy" below). However, because Lincoln wrote on both sides of the paper, the speech could not be reprinted, so Lincoln made another copy at Bliss's request. It is the last known copy written by Lincoln and the only one signed and dated by him. Today it is on display at the Lincoln Room of the White House.

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate — we can not consecrate — we can not hallow — this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Abraham Lincoln

November 19, 1863

Here is one oral delivery of the Gettysburg Address that lasts two minutes and forty-six seconds. At 1:39, you will see a plain tombstone that says only:

PENNSYLVANIA

534 BODIES

on a background of short, green grass.

On my run across the country on Route 30 / Lincoln Highway, I spent three days in Gettysburg to pay my respects to those who perished there — from both sides.

Imagine what the world would be like today if the United States of America had sundered into two nations one hundred and sixty years ago.

Selected readings

- "Speech rhythm in Visible Speech" (12/18/13)

- "Cumulative syllable-scale power spectra" (6/11/19)

- "John DeFrancis, August 31, 1911-January 2, 2009" (1/26/09)

- Schriftfestschrift: Essays in Honor of John DeFrancis on His Eightieth Birthday, Victor H. Mair, ed., Sino-Platonic Papers, 27 (August, 1991), ix, 245 pages

- John DeFrancis (Wikipedia)

- John DeFrancis (Wenlin)

- "Machine translators vs. human translators" (1/7/25)

David Morris said,

January 19, 2025 @ 3:21 am

"Four score and seven years ago" is a classic example, where the "f" sound is repeated.

Maybe ask ChatGPT how many 'f's there are in that sentence.

Michael Carasik said,

January 19, 2025 @ 4:09 am

The speech was given about a year and a half before he was shot — not six weeks.

Graham Perrin said,

January 19, 2025 @ 4:14 am

Commenter David Morris wondered whether to ask ChatGPT about repetition of the "f" sound.

I took a traditional approach; I took time to read more of what Victor Mair wrote. He quoted:

"Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth …".

Philip Taylor said,

January 19, 2025 @ 4:40 am

A better image of the front cover can be found here.

Victor Mair said,

January 19, 2025 @ 5:24 am

That particular copy means a lot to me. I was deeply involved in its making.

Victor Mair said,

January 19, 2025 @ 8:29 am

From Leslie Katz:

When reading the above, I was struck by the following: "He did not dash off the speech on a trundling train from Washington through Hanover Junction, Pennsylvania to Gettysburg. Two copies of the text were written in Lincoln's steady hand on a stable surface before delivery."

Perhaps you already know this, but, just in case you don't and may be amused by it, that's reasoning reminiscent of Sherlock Holmes.

In the short story "The Adventure of the Norwood Builder", Holmes examines a will and says,

Philip Taylor said,

January 19, 2025 @ 1:00 pm

It would seem that there are at least two subtly different versions of that anecdote, Leslie — I know the last clause as "stopping only once between Norwood and London Bridge". I wonder which is to be found in the MS (assuming that there is only one MS, of course).

David Morris said,

January 19, 2025 @ 3:40 pm

@Graham Perrin: Thank you. Thank makes sense now.

Laura Morland said,

January 19, 2025 @ 8:01 pm

@David Morris – I thank you for my first real chuckle of the day.

For those not in the know : https://youtu.be/wz5hsIw9mQc?si=O9zVjxEX-RiJHK8c

Laura Morland said,

January 19, 2025 @ 8:05 pm

@Victor Mair, that's why God invented ellipses.

(It would have eliminated David Morris' and my puzzlement, had you included them after "ago".)

Beautiful post!

/df said,

January 20, 2025 @ 12:27 am

Given Monday's scheduled event, maybe this from more than 8 years ago is another candidate "Selected reading"?

Mark S. said,

January 20, 2025 @ 9:01 am

DeFrancis also discusses the "Singlish" version (not to be confused with Singapore English) of this in The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy, concluding with the following "dread decree":

"Anyone who believes Chinese characters to be a superior system of writing that can function as a universal script is condemned to complete the task of rendering the whole of Lincoln's Gettysburg Address into Singlish."

Yves Rehbein said,

January 24, 2025 @ 1:09 pm

I clicked to embiggen, it is badly pixelated but I can read the Egyptian: fr skr And swn iirs a…, except for the last two signs, g and wA.

Now to the cuneiform, I did not know that the sign GEŠ (third to the left) could transliterate initial s. Since it seems to come from a proto-cuneiform quadrilateral later used as logogram for iṣum "tree, wood", the similarity to Egyptian š (a quadrilateral) and šn "tree" is striking. NB: "The common Sino-Tibetan root for “tree; wood” is *siŋ ~ sik, represented by 薪 (OC *siŋ, “firewood”)." https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/木 I doubt the proto-cuneiform identification (a square) because of Sinitic phonophore 爿 OC *braːn, *zaŋ, “bed” https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/牀 GEŠ being the common determiner for furniture. In syllabic writing it spells es https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cuneiform#Syllabary Annecdotally, the name of the Skythians is rendered in Akkadian Iš-ku-za-a and Aš-ku-za-a, and the Arabic transcription of /sk/ uses an initial aleph as well.

What are the odds that sī 斯 "this" OC *se as is used in this transcription or "phonetic translation" https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/斯#Usage_notes has the same semantophore 斤 which, if it is a qiāng 斨 "axe" OC *sʰaŋ used to xī析 "to split wood" OC /*[s]ˁek/ "split (v.)", might also work as a phonophore?!? In the other character component "… 丌 was added under the basket to represent a stand." https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/其 Note that 囗 is implicated indirectly by 箕 ⿱其 with 竹 ⿰亇亇 and variants (個/个 "single"). 個 phonetic 固 /*[k]ˤa-s/ "fortified, secure" ⿴囗古, 囗 "Pictogram of a square-shaped enclosure." https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/囗 is distinguished from 古. The shape housing OBI 爿 might be significant. Akkadian sikkanum vel sim. "stone stele" is out of my reach for the time being.

That would bring me to the fourth character in the row but the image is honestly too blurry to confirm 國!