"Calling all linguists"

« previous post | next post »

Kevin Drum, "Calling all linguists", 10/20/2023:

You know what I'd like? I'd like a qualified linguist with a good ear to listen to a Joe Biden speech and report back.

A couple of weeks ago I spent some time doing this, and Biden's problem is that his speech really does sound a little slurred at times. My amateur conclusion was that he had problems enunciating his unvoiced fricatives, which suggests not a cognitive problem but only that his vocal cords have loosened with age.

I don't have time this weekend to answer Mr. Drum's call, at least not in an adequate way, so I'll give a very brief response and then open the floor to commenters.

First, two things about his request puzzle me:

- There are certainly age-related changes in the vocal folds, but it's misleading to describe the changes as "loosening".

- In any event, changes in the vocal folds should not have any effect on most "unvoiced fricatives", in which the vocal folds are fully open, permitting air to pass freely into the supra-laryngeal vocal tract, where a narrow constriction creates turbulent flow and therefore noise. (I presume that we're not talking about the laryngeal fricative /h/, or at least not only about /h/…)

Terminology and physiology aside, we can start with the idea that what Drum hears in Biden's speech is "problems enunciating" the voiceless fricatives /f/, /θ/, /s/, /ʃ/ — and I guess we should look at /h/ as well.

And there are plenty of Biden recordings at whitehouse.gov and on YouTube, most recently his Oval Office address on the Israel-Hamas War.

The audio from that last address can be found here, and I have to say that on a quick listen, I don't hear any problems with the voiceless fricatives. Here's his first sentence, which has two instances of /s/, two instances of /f/, and one of /h/ (or really /ɦ/, though the voicing is normal in that context…):

What I do hear (at least in that sentence) is some extra lenition or coarticulation in and around some of the unstressed syllables.

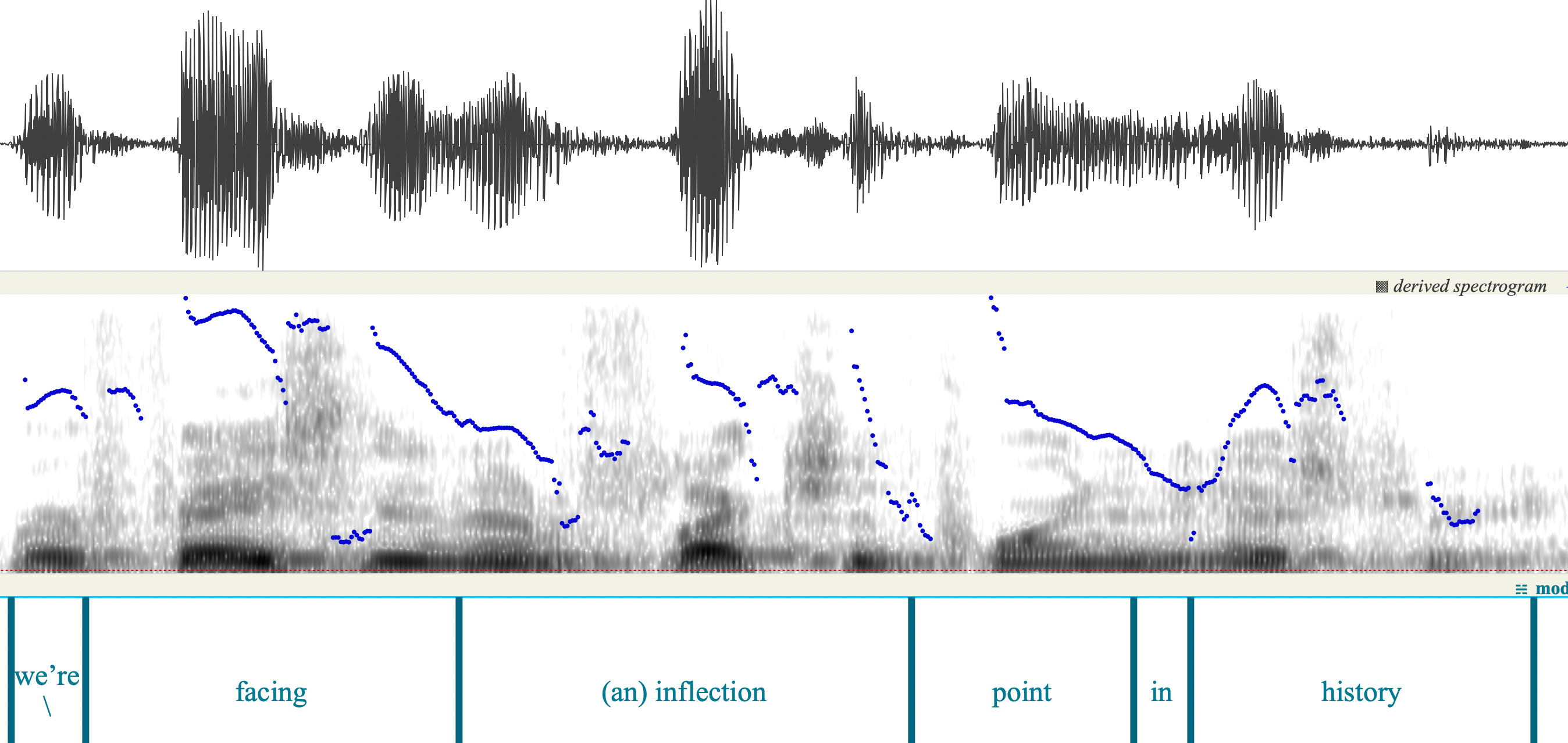

Thus the first two syllables of the sequence "an inflection" are blended into one:

That's something that any American speaker might do in rapid casual speech — essentially deleting the nasal flap expected for the /n/ of "an" — but it's unexpected (at least to me) in the opening of a formal address.

And the /t/ of "point" is lenited towards non-existence, and the resulting final nasal is kind of merged with the following "in":

It's normal for word-final /t/ to be voiced and flapped before a word-initial vowel; and American English "flaps" often turn into approximates; but again, it's a little unexpected in the context.

This is a totally inadequate response to Mr. Drum's call, based on analyzing one sentence in one speech.

But I don't think what I've described is evidence of cognitive decline. Most likely, President Biden talked this way when he first entered politics — though again, I don't have time to look into it properly today, and so I'll leave it there and turn things over to the commentariat.

(And I'll ask Mr. Drum to give us some specific examples, in this speech or another one, where he perceives problems with unvoiced fricatives…)

Update — To follow up on Bloix's comment, referencing an earlier comment that suggested Biden "prevents blocks by liquifying plosive consonants when he anticipates trouble": In a January 2020 Atlantic article, John Hendrickson interviews Biden about how he experienced and overcame stuttering. Hendrickson discusses his own experience with stuttering, remembering what he learned from therapy with Joseph Donaher at CHoP:

Donaher and his colleagues try to help their patients open up about the shame and low self-worth that accompany stuttering. Instead of focusing solely on mechanics, or on the ability to communicate, they first build up the desire to communicate at all. They then share techniques such as elongating vowels and lightly approaching hard-consonant clusters, meaning just touching on the first sound in a word like stutter—the st—to keep the mouth and throat from tensing up and interfering with speech. The goal isn’t to be totally fluent but, simply put, to stutter better.

Apparently Biden learned to overcome his speech impediment to a large extent on his own:

After trying and failing at speech therapy in kindergarten, Biden waged a personal war on his stutter in his bedroom as a young teen. He’d hold a flashlight to his face in front of his bedroom mirror and recite Yeats and Emerson with attention to rhythm, searching for that elusive control.

It's plausible that this self-guided practice reinforced therapists' earlier attempts at some form of "gentle onset" therapy. In any case, the speech characteristics that Kevin Drum noticed are surely the (complex) effects of Biden's learned approaches to fluency, and not a symptom of aging vocal folds.

Hendrickson also offers this:

Emma Alpern is a 32-year-old copy editor who co-leads the Brooklyn chapter of the National Stuttering Association and co-founded NYC Stutters, which puts on a day-long conference for stuttering destigmatization. Alpern told me that she’s on a group text with other stutterers who regularly discuss Biden, and that it’s been “frustrating” to watch the media portray Biden’s speech impediment as a sign of mental decline or dishonesty.

Peter B. Golden said,

October 21, 2023 @ 4:03 pm

I have no knowledge of the physiological aspects of this. It should be borne in mind that Biden was a stutterer as a child and has dealt with that since then. His occasional blurring of words may stem from that.

J.W. Brewer said,

October 21, 2023 @ 4:17 pm

There is lots of archival video of Biden speechifying and bloviating well back into the 20th century, so it ought to be easy with a large enough historical sample to assess whether any features of his current speech that strike someone as disfluent are new developments or long-standing things. Whether any actual changes over time are consistent with what you would expect from someone who is X decades older but has not cognitively declined could then be assessed. (Of course, from a baseline perspective, no one ever claimed back when Biden was in his thirties, forties, or fifties that he was one of the more cognitively gifted members of the U.S. Senate, which is not on average a particularly cognitively-gifted assemblage.)

Seth said,

October 21, 2023 @ 4:39 pm

I suspect it is possible that an expert neurologist might sometimes be able to analyze a politician's speech, and detect whether there is an unobvious but serious neurological issue. The sad problem is that there is no way in the current media ecosystem to figure out who is such a real expert, versus a media "expert" being (mis)quoted because they make for a good story.

In this case, the problem is compounded by the factor that being extremely stressed and tired (as will happen with any President at times) may create speaking errors which can be confused with cognitive problems.

Further, not all cognitive problems are evident in a formal speech. This is particularly significant for politicians who have made a career of public speaking. Reportedly, Ronald Reagan could still deliver an excellent (written by someone else) public speech, even when he was in serious mental decline from Alzheimer's disease. That skill was supposedly one of the last things to be affected.

Here's an interesting article, this analysis could easily be done:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6922000/

"Tracking Discourse Complexity Preceding Alzheimer's Disease Diagnosis:

A Case Study Comparing the Press Conferences of Presidents Ronald Reagan and George Herbert Walker Bush"

Mark Liberman said,

October 21, 2023 @ 5:12 pm

@Seth:

We've covered many aspects of such work, and done some of it ourselves. But as you point out, little to none of this applies to the delivery of a pre-composed speech — the main source of problems there would be one kind or another of motor speech disorder, not all of which are associated with aging.

Anyhow, a sample of earlier posts, FWIW:

"Writing style and dementia", 12/3/2004

"Nun study update", 8/27/2009

"Literary Alzheimer's", 12/13/2009

"Authorial Alzheimer's again", 12/15/2009

"Words and ag", 12/23/2009

"Early Alzheimer's signs in Reagan's speech", 4/12/2015

"Ross Macdonald: lexical diversity over the lifespan", 1/13/2018

"'Project Talent' adds to long-range dementia predictions", 10/1/2018

"New approaches to Alzheimer's Disease", 4/8/2020

"Praise for clinical applications of linguistic analysis", 5/10/2022

AG said,

October 21, 2023 @ 6:44 pm

There's no well-known and common condition for how old people often sound like they are fighting to get the sounds out from around dentures (whether they have them or not?) Fatigued lips or wrinkletongue or something? The characteristic effect seems nearly universal and very noticeable to me.

Bloix said,

October 21, 2023 @ 9:57 pm

Three years ago Victor Mair wrote a post about an incident in which Biden's stutter got the better of him. I wrote a comment in which I gave my totally unprofessional opinion regarding Biden's speech, especially what I called his "unusually soft sound:"

Victor responded, "Thank you for your brilliant comment."

I wouldn't have gone that far, but perhaps what I had to say then – correct or not – might contribute to the discussion.

David Marjanović said,

October 21, 2023 @ 10:23 pm

I think what Biden does to point in is to reduce unstressed in to a syllabic nasal. /t/ followed by one of those (e.g. in button) routinely turns into a glottal stop even in AmEng. This glottal stop then gets voiced and nasalized, both of which are impossible, so you end up with a syllabic nasal that has some amount of creaky voice in it. I don't have time to check either, but I expect Biden has always talked like that; lots of people do.

Yuval said,

October 22, 2023 @ 4:29 am

[there are two instances of /f/ in there, not one.]

Jerry Packard said,

October 22, 2023 @ 11:46 am

A linguist responding to the call. We lose the strength and power of our speech articulation as we age, becoming most apparent in our 80s and 90s. Now in our early 70s my spouse and I have to work harder to make ourselves understood even sitting just a couple of feet from each other. If you compare Biden’s speech then & now it is readily apparent, with the earlier Biden able to speak with much greater force and clarity.

ajay said,

October 24, 2023 @ 9:08 am

(Of course, from a baseline perspective, no one ever claimed back when Biden was in his thirties, forties, or fifties that he was one of the more cognitively gifted members of the U.S. Senate, which is not on average a particularly cognitively-gifted assemblage.)

Are you seriously equating speech impediments with stupidity?

Sorry, silly question. Obviously you are.

J.W. Brewer said,

October 24, 2023 @ 10:42 am

@ajay: I was not trying to make that equation, but the premise of the Kevin Drum question myl was addressing was exactly that some people might well interpret changes in speech in an aging individual as evidence of cognitive impairment, such that Drum was apparently shopping for an alternative benign explanation having to do with physiological effects of aging with no connection to cognitive functioning.

But to the extent one heard gossip from political insiders in long-ago decades that Biden was one of the dimmer bulbs in a Senate full of dimbulbs, I don't recall anything about his speech being referenced as the evidentiary basis for that assessment. Or rather, people might point to him as being a fatuous blowhard who said very little of substance, but that is a fairly common trait of politicians and not what a clinician would call an "impediment."

ajay said,

October 25, 2023 @ 3:10 am

I am not trying to make that equation!

(proceeds to make that equation, again)

Natasha Warner said,

October 25, 2023 @ 8:23 am

The reduced speech points you mention in things like "an inflection" and "point in" are absolutely normal even in extremely formal, careful speech like an important person giving a speech. My research area is reduced speech, which we usually look for indeed in spontaneous conversation. But I'm a department head, so I spend a lot of time hearing deans and even the university president giving formal speeches. When I'm bored in meetings, I listen to the speaker's phonetics for entertainment. I've noted down many examples of people up through the university president in a speech to the board of regents reducing speech in exactly these sorts of ways (ex.: 'operating room' with the flap not just lenited but deleted, in a discussion of the university hospital's revenue flow). I hear it from newscasters too (e.g. 'senator' with the flap completely deleted), another place where we expect super-careful speech. Early in the pandemic, I listened to my university president's weekly updates and sent out summaries to my department. I started including a "linguistic observation" about some interesting thing one of the speakers said each week, for entertainment value. I could always find a nice drastic reduction to use as the linguistic observation, even if I ran out of ideas for anything else to notice, even though all the speakers were leaders addressing an audience of journalists and presumably were using their most careful connected speech. So I see nothing strange about Biden's reductions in the post above at all, even in the most formal speech register. That's not age or evidence of his being a stutterer, that's just normal communication.