Words and age

« previous post | next post »

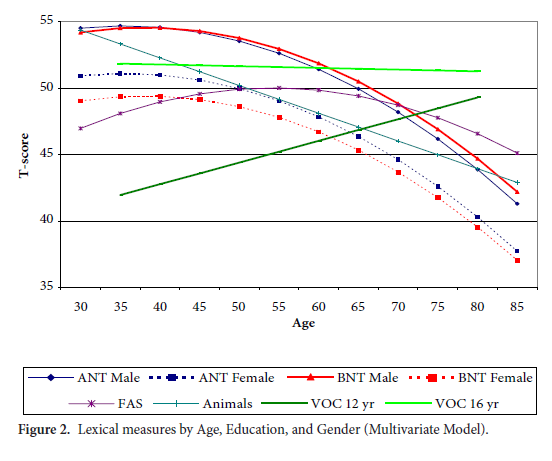

To follow up on our recent discussion of the effects of Alzheimer's disease on the writing of Iris Murdoch and Agatha Christie ("Literary Alzheimer's"; "Authorial Alzheimer's again"), I promised to post about the broader linguistic background, starting with a discussion of the normal effects of aging. With respect to lexical issues, there's a useful, if complicated, summary graph in a recent review paper coming out of the Language in the Aging Brain project (Mira Goral et al., "Change in lexical retrieval skills in adulthood", The Mental Lexicon 2: 215–240, 2007):

(Note that these are schematic plots from their statistical model, not the average values being modeled, much less the trajectory of any individual. The data comes from a "longitudinal data from 238 adults, ranging in age from 30 to 94, who were tested … over a period of 20 years".)

There are five lexical tests represented here, two picture-naming tests (the "Boston Naming Test" and the "Action Naming Test"), two list-generation tests ("FAS" and "Animals"), and the vocabulary subtest of the WAIS-R.

The results for the WAIS-R vocabulary test are plotted separately for two subgroups, those with a college or post-graduate degree ("VOC 16 yr", i.e. 16 or more years of education) and those with only a high-school education ("VOC 12 yr"). For (model fit for) the high-school group, this measure of vocabulary increases linearly throughout life. For the college group, the WAIS-R vocabulary measure doesn't change over the age-range tested. (I presume that this is a sort of ceiling effect, and that a different vocabulary test would show increases with age for the college sub-group as well — though this is sheer speculation.)

In the animal-naming task, participants were asked to list as many animals as they could within one minute. This measure (in themodel fit) declined linearly thoughout the range of ages covered.

The "FAS" naming task requires subjects to list as many words as they can starting with the letter 'F' (excluding names and variant forms of words already listed), and then to do the same for 'A' and 'S'. They have one minute for each letter. On this task, (the model says that) subjects improved up to about age 55, and then declined.

The Boston Naming Test (BNT, Kaplan et al., 1983) comprises 60 line drawings of objects ranging from very common items, such as bed and tree, to less-common items, such as unicorn and protractor. Participants were presented with one picture at a time (e.g., a volcano) and were asked to say the label for it. If they could not name the picture within 20 seconds, they were given a semantic cue (e.g., a kind of mountain) and if they still could not name it they were given a phonemic cue (the first phonemes of the target word, e.g., /vә/). The dependent measure was percent correct before phonemic cues.

As you can see from the graph, the model showed an accelerating decline with age for scores on the BNT, and a difference between men and women (with men having higher scores overall).

The Action Naming Test (ANT, Obler & Albert, 1979) comprises 55 line drawings of actions ranging from very common activities, such as eating and reading, to less-common items such as proposing and knighting. As in the BNT, if needed, participants were given first a semantic cue and then (if needed) a phonemic cue. The dependent measure was percent correct before phonemic cues.

The model also showed an accelerating decline with age for the ANT, and also an advantage for males.

Some interactions reported in the paper but not shown in the graph: individuals with more education had higher scores on the FAS and animal-naming tasks; on the BNT, women with more education had higher scores, while there was no significant effect of education for men.

Again, it's important to recognize that these are interpreted parameters of a (rather complex) model fit to their data, not the data itself:

Initially, we analyzed available data for each of the five measures separately, to identify the “best” model for each measure. As fixed effects, we considered age, education, gender and their interactions; random effects consisted only of age (as linear and quadratic terms). The best model was that with the lowest value of Akaikes information criterion (AIC), a measure of overall fit. Subsequently, we combined the best model for each measure into a multivariate model, which estimated change in each outcome simultaneously and allowed us to examine correlations among levels and slopes for the measures. Such “correlated change” models have been used to investigate relations among changes in multiple measures of cognition over time. With a multivariate, correlated-change model, we can determine the extent to which change in one measure is associated with change in another.

The point is not that the model is inappropriate or wrong, or that the conclusions are questionable — the cited effects are confirmed in general terms by other studies — but that it's a summary of trends and tendencies in many measures on a large group of subjects, and not necessarily a fact about any particular individual.

The authors observe that different tasks show a range of different relationships to age, sex, and level of education, and specifically that "the tasks that required retrieval of unique lexical items (Boston Naming Test and Action Naming Test) yielded significant age-related decline that became more rapid in older age, distinguishing them from tasks that allowed for the retrieval of various lexical items", and also from tasks that required response to lexical items provided by the experimenter.

They suggest that some of these differences can be explained by "a cascaded progression of lemma and lexeme retrieval during word production". By lemma they mean (roughly) the concept associated with a word, while lexeme means the word itself. It may help to understand this distinction by supposing that when a word is "on the tip of your tongue", you've got the lemma but can't quite get the lexeme. (Warning: these terms are used somewhat differently in other areas of linguistics, e.g. by lexicographers or morphologists.)

The difficulty that some older adults experience with picture-naming tasks can be explained within the framework of the Transmission Deficit Hypothesis (TDH) developed by Burke and her colleagues based on D. MacKay’s Node Structure Theory (NST) (e.g., Burke et al., 1991). In the NST, the representational units, termed nodes, are interconnected. Lexical nodes are connected to semantic nodes in the semantic system and to phonological nodes in the phonological system. Word production involves activation of the relevant semantic nodes, which in turn prime the phonological nodes that are connected to the word. The strength of the connections between nodes will determine the amount of priming transmitted between them. According to the TDH, in older age the strength of these connections is reduced and so transmission of priming among nodes is reduced.

On the face of things, this theory also seems to predict age-related decline in vocabulary tests, since the same connections are involved in the opposite direction. But perhaps learning new words overcomes any degradation in the connections for old words, or receptive connections are reinforced in ways that production connections are not, or something.

Anyhow, my main point here is a descriptive one: overall, as we get older, we're likely to have increasing difficulty with tasks that require retrieval of particular words from meanings. It's comforting to observe that networked computer technology is increasingly able to assist our aging brains with such tasks.

Dan Lufkin said,

December 23, 2009 @ 11:35 am

I might well be one of the data points on that graph. For more than 20 years I've been in an NIH longitudinal study that features the animal-naming test and the Boston naming-test, along with lots of other reminders of decrepitude.

Subjectively, the problem with the animal-naming test is that (at 79) I know a great many more animal names now than I did at age 30 and the background noise from Trumbull's lesser wallaby and its ilk tends to slow retrieval of kangaroo. I'm also on a first-name basis with lots of volcanoes, with a similar result. A couple of months ago the BNT insisted that a picture of a hasp was actually that of a latch and the tester wouldn't give me credit.

Again subjectively, I'm keenly aware that I have a problem retrieving proper names, but the fact that I've known a whole lot of people doesn't seem to play much of a role there.

Mark P said,

December 23, 2009 @ 11:57 am

It sounds like the TDH is a theory based on a sort of observed, apparent function rather than the actual physical process that results in the observed function. I suppose as more is learned about the actual brain processes we will understand more about what's actually happening in age-related cognitive decline.

I would probably have more trouble with some of these tests now than I would have had at an earlier age because I have less patience with that sort of thing. At least that's my story. And I find more and more that Google is my friend.

Rubrick said,

December 23, 2009 @ 11:58 am

A couple of months ago the BNT insisted that a picture of a hasp was actually that of a latch and the tester wouldn't give me credit.

Showing that, aged 9 or 79, a student whose understanding exceeds his teacher's always gets screwed.

Robert T McQuaid said,

December 23, 2009 @ 5:42 pm

Interesting research, but there is no discussion of one possible fallacy. Attitudes toward food waste vary with age, but not because of aging. The main factor is whether the subject lived through a period of food shortage. Among Americans that means the great depression, leading to the fallacious result that in old age people become less tolerant of food waste. In the language research, the results could be biased by different educational (or other) practices in past decades.

Ran Ari-Gur said,

December 23, 2009 @ 11:31 pm

@Robert T McQuaid: What you describe is a limitation of cross-sectional studies, but this one is a longitudinal study: they're not directly comparing the older adults to the younger ones, but rather, comparing each participant's later scores to earlier ones. That's not to say that factors like what you describe can't affect the results, but their effects shouldn't be so drastic, at least.

linda seebach said,

December 24, 2009 @ 1:08 am

Given the differences in life expectancy, is it possible that the male-female difference is partly accounted for by the fact that at any given age, more of the weaker males have already died?

Mike Maxwell said,

December 24, 2009 @ 10:55 pm

"less-common items, such as…protractor." Hmm, these were standard issue back in my days, but I'm not sure my kids have even seen one. Maybe they should include pictures of slide rules, meat grinders, tire jacks, milk bottles, can openers, typewriters, and tape cassettes. Then us old fogies could really shine!