Where did the PIEs come from; when was that?

« previous post | next post »

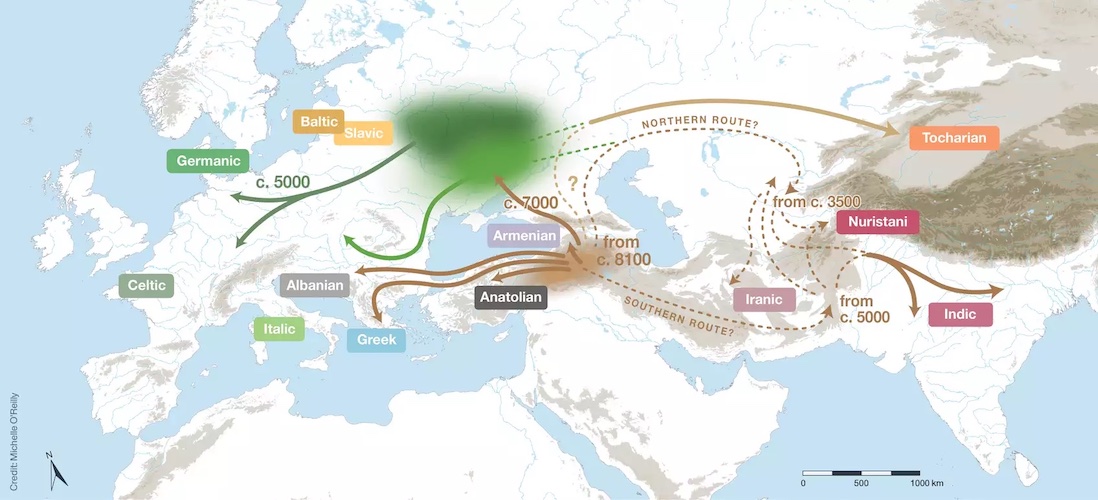

The language family began to diverge from around 8,100 years ago, out of a homeland immediately south of the Caucasus. One migration reached the Pontic-Caspian and Forest Steppe around 7,000 years ago, and from there subsequent migrations spread into parts of Europe around 5,000 years ago. Credit: P. Heggarty et al., Science (2023)

"New Insights into the Origin of the Indo-European Languages. Linguistics and genetics combine to suggest a new hybrid hypothesis for the origin of the Indo-European languages." Max-Planck-Gesellschaft (7/27/23). Also PhysOrg, July 27, 2023. Discussing "Language Trees with Sampled Ancestors Support a Hybrid Model for the Origin of Indo-European Languages." Heggarty, Paul et al. Science 381, no. 6656 (July 28, 2023): eabg0818.

Précis

An international team of linguists and geneticists led by researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig has achieved a significant breakthrough in our understanding of the origins of Indo-European, a family of languages spoken by nearly half of the world’s population.

Introduction

For over two hundred years, the origin of the Indo-European languages has been disputed. Two main theories have recently dominated this debate: the ‘Steppe’ hypothesis, which proposes an origin in the Pontic-Caspian Steppe around 6000 years ago, and the ‘Anatolian’ or ‘farming’ hypothesis, suggesting an older origin tied to early agriculture around 9000 years ago. Previous phylogenetic analyses of Indo-European languages have come to conflicting conclusions about the age of the family, due to the combined effects of inaccuracies and inconsistencies in the datasets they used and limitations in the way that phylogenetic methods analyzed ancient languages.

To solve these problems, researchers from the Department of Linguistic and Cultural Evolution at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology assembled an international team of over 80 language specialists to construct a new dataset of core vocabulary from 161 Indo-European languages, including 52 ancient or historical languages. This more comprehensive and balanced sampling, combined with rigorous protocols for coding lexical data, rectified the problems in the datasets used by previous studies.

Indo-European estimated to be around 8100 years old

The team used recently developed ancestry-enabled Bayesian phylogenetic analysis to test whether ancient written languages, such as Classical Latin and Vedic Sanskrit, were the direct ancestors of modern Romance and Indic languages, respectively. Russell Gray, Head of the Department of Linguistic and Cultural Evolution and senior author of the study, emphasized the care they had taken to ensure that their inferences were robust. “Our chronology is robust across a wide range of alternative phylogenetic models and sensitivity analyses”, he stated. These analyses estimate the Indo-European family to be approximately 8100 years old, with five main branches already split off by around 7000 years ago.

These results are not entirely consistent with either the Steppe or the farming hypotheses. The first author of the study, Paul Heggarty, observed that “Recent ancient DNA data suggest that the Anatolian branch of Indo-European did not emerge from the Steppe, but from further south, in or near the northern arc of the Fertile Crescent — as the earliest source of the Indo-European family. Our language family tree topology, and our lineage split dates, point to other early branches that may also have spread directly from there, not through the Steppe.”

New insights from genetics and linguistics

The authors of the study therefore proposed a new hybrid hypothesis for the origin of the Indo-European languages, with an ultimate homeland south of the Caucasus and a subsequent branch northwards onto the Steppe, as a secondary homeland for some branches of Indo-European entering Europe with the later Yamnaya and Corded Ware-associated expansions. “Ancient DNA and language phylogenetics thus combine to suggest that the resolution to the 200-year-old Indo-European enigma lies in a hybrid of the farming and Steppe hypotheses”, remarked Gray.

Wolfgang Haak, a Group Leader in the Department of Archaeogenetics at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, summarizes the implications of the new study by stating, “Aside from a refined time estimate for the overall language tree, the tree topology and branching order are most critical for the alignment with key archaeological events and shifting ancestry patterns seen in the ancient human genome data. This is a huge step forward from the mutually exclusive, previous scenarios, towards a more plausible model that integrates archaeological, anthropological and genetic findings.”

With these new findings, we may compare the lengthy, much discussed studies of our colleague Don Ringe (listed in the bibliography below [first seven items]).

Selected readings

- "The Linguistic Diversity of Aboriginal Europe" (1/6/09) — classic post by Don Ringe

- "Horse and wheel in the early history of Indo-European" (1/10/09)

- "More on IE wheels and horses" (1/10/09)

- "Inheritance versus lexical borrowing: a case with decisive sound-change evidence" (1/13/09)

- "The linguistic history of horses, gods, and wheeled vehicles" (1/13/09)

- "Some Wanderwörter in Indo-European languages" (1/16/09)

- "Don Ringe ties up some loose ends" (2/20/09)

- "The place and time of Proto-Indo-European: Another round" (8/24/12)

- "Proto-Indo-European laks- > Modern English 'lox'" (12/26/20)

[Thanks to Ted McClure]

——

Earlier suggestions by Ted McClure that may be of interest to LL readers

- "What Is Written on a Dog's Face? Evaluating the Impact of Facial Phenotypes on Communication between Humans and Canines." Sexton, Courtney L. et al. Animals 13, no. 14 (July 22, 2023): 2385. .

- "Neural Basis of Sound-Symbolic Pseudoword-Shape Correspondences." Barany, Deborah A. et al. bioRxiv, April 14, 2023. . Preprint.

- "Semantic Noise in the Winograd Schema Challenge of Pronoun Disambiguation." de Jager, S. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 10, no. 1 (April 11, 2023). .

- "Determining the Cognitive Biases behind a Viral Linguistic Universal: The Order of Multiple Adjectives." Leivada, Evelina. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 9, no. 1 (December 5, 2022): 1-13. .

- "Dependency Distance Minimization: A Diachronic Exploration of the Effects of Sentence Length and Dependency Types." Liu, Xueying et al. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 9, no. 1 (November 26, 2022). .

- "World's Largest Grammar Database Reveals Accelerating Loss of Language Diversity." Simpkins, Kelsey. CU Boulder Today, April 19, 2023. . Discussing "Grambank Reveals the Importance of Genealogical Constraints on Linguistic Diversity and Highlights the Impact of Language Loss." Skirgård, Hedvig et al. Science Advances 9, no. 16 (April 19, 2023): eadg6175.

Ben Zimmer said,

July 28, 2023 @ 2:46 pm

A note of skepticism from Andrew Garrett in the Globe and Mail:

Sally Thomason said,

July 28, 2023 @ 3:58 pm

I second Garrett's skepticism (and his praise for value of the dataset). The proposed 7000 years of divergence of IE languages is still in conflict with the evidence from linguistic archaeology — terms in Proto-Indo-European for wheels, yokes, and other things associated with wheeled vehicles and domesticated horses, for instance — which point to a later date of divergence of the IE branches from PIE, and to a Steppe origin. It would be nice if controversial hypotheses were presented to Language Log readers with more caution.

Victor Mair said,

July 28, 2023 @ 4:03 pm

Well, the caution came nicely and swiftly from Andrew Garrett, Ben Zimmer, and Sally Thomason, not to mention our own Don Ringe, whose works I cited at length in the o.p., especially concerning wheels, horses, gods, etc.

Sean M said,

July 28, 2023 @ 4:16 pm

My first impression was that this article seems similar to the piece in Science with Quentin Atkinson from 2012, corrected in response to some of the criticism by linguists (eg. Romani has apparently been removed from the list of languages), but not citing the book by Pereltsvaig and Lewis which was the best single source for that criticism. That is just a provisional response from a historian based on a few quick sanity tests.

Andrew Garrett said,

July 28, 2023 @ 4:46 pm

For those who like to get their scholarly discourse from pithy take-downs in a social forum governed by a right-wing lunatic, I wrote a Twitter thread about this here:

https://twitter.com/ndyjroo/status/1684636445854875648

Sean M said,

July 28, 2023 @ 9:33 pm

Andrew Garrett: I am glad to hear that the corpus of cognates is useful whatever one thinks of the phylogenetics! (And I'm not really qualified to comment on the details). Thanks for the link to the site with the IE-CoR corpus, I will explore it.

Chris Button said,

July 29, 2023 @ 8:11 am

Seeing as this thread seems to have attracted some PIE specialists, and the topic of controversial hypotheses has come up, I wonder if I might pose a speculative hypothesis around a classic problem of PIE phonology?

(b-) d-, g- is a well-known problem in PIE when b-, d-, (g-) would be expected since it’s hard to maintain voicing on a velar stop.

A nice example is in Sizang Chin (a Tibeto-Burman language on the Burma-India border) where the language has not simply deployed the classic prenasalization trick to maintain the voicing on a velar g- but has then gone on to fully nasalize the stop. The result is that original g- has completely merged with the velar nasal ŋ- to leave just b- and d-.

The Sizang evolution makes good phonetic and typological sense. Why then does PIE appear to have lost b- instead?

It occurs to me that perhaps PIE deployed the same protective prenasalization but then resolved it differently. Could g- and also d- have developed prenasalized allophones while b- remained unaffected because it was less necessary for articulatory reasons? The prenasalization then became encoded in g- and d- thereby flipping the ability of the stops to maintaining voicing—namely g- and d- are now better able to maintain voicing than b-. And as a result, at a later stage of the language, b- loses voicing to merge with p- and leave d- and g-.

I suppose the idea that b- merged with p- takes it leads from Holger Pedersen’s old proposal but the typological grounds are different and it doesn’t entail all the other flipping of voiced and voiceless stops that he proposes.

Matt said,

July 29, 2023 @ 8:35 am

This paper is a step forwarding in solving the fine-detail (among recent family) problems that were an issue with previous analyses, and the issues of ancient languages being placed on long side branches to modern ones. These were main areas of criticism of previous papers and seem largely resolved.

But the linguistic paleontology problem still remains and is unconvincingly resolved (it seems impossible to have independent parallel construction of terminology in long diverged languages), and the paper does not really explain how already 2000 year diverged Baltic-Slavic and Celtic-Germanic-Italic groups can both associated with the a population expansion from the steppe to the North and West at ~3000 BCE.

The way forward will probably on two fronts:

1) Mathematically and statistically, to resolve with simulations whether we can really be confident about the age of unobserved languages when we only have recent sampled varieties that may have been changing at a different rate from the unsampled variety. Say in a simulated tree there is lexical substitution at 2x rate in a small group of unsampled ancestors compared to their observed descendents; how probable is this, how well do tree algorithms cope with it and ultimately does this bias or render impossible any purely lexical attempt to estimate age of a central ancestral node? How probable is it that trees demonstrated for other language families so far have been "right" by chance?

2) Linguistically, does the lexicon of reconstructed proto-language forms implied by the trees here, and which can no doubt be exported from the software as a list, really hold up to scrutiny from historical linguists? (It is possible that the forms may lead to a reassessment of either the data here, or the proto-languages as understood).

Chris Button said,

July 29, 2023 @ 12:10 pm

And if I may be permitted another, hopefully not too naive, question, I note with interest the suggestion the non-standard proposal for uvular onsets in PIE. That seems to chime well with the idea that the laryngeals h2 and h3 were (phonetically at least) respectively voiceless and voiced uvular fricatives. However, what surprises me is that the uvular series of stops was not suggested to replace the labiovelar series of stops with its rather restricted distribution (in particular relative to the plain stops, albeit without cases as extreme as the lack of b- but getting there in particular with the “voiced aspirate”).

The tendency of uvulars to retract vowels and subsequently sometimes cause rounding (the association of rounding with back vowels being well-attested) has been independently noted in Old Chinese by Pulleyblank, Pan Wuyun and Jin Lixin, albeit in slightly different ways, to avoid positing an overtly labial phoneme. Might we consider applying a similar line of thought to PIE?

Sally Thomason said,

July 29, 2023 @ 3:03 pm

@Chris Button, about those uvulars: a (maybe the) major problem with the PIE laryngeals as uvulars is that the PIE phonemes don't act like fricatives. They pattern with resonant consonants like l, r, m, n, w, and y. At least two of them do, however, resemble resonant pharyngeal consonants in modern Salishan languages like Selis-Ql'ispe (a.k.a. Montana Salish), where the plain pharyngeal (not labialized, not glottalized) phoneme retracts vowels and vocalizes into [a] when not next to a vowel phoneme, and the labialized nonglottalized pharyngeal phoneme retracts vowels and vocalizes into [o] when not next to a vowel phoneme. The vowel retraction is what you'd expect with a uvular consonant (and that happens in Salish too, because it also has plain and labialized uvular fricatives), but the vocalization is not. (The two glottalized pharyngeal phonemes in Salish don't fit into a PIE framework, alas.) All four pharyngeal phonemes have been lost in many or most Salishan languages, and they're kinda unstable even in the languages that still have them — they often disappear without a trace in unstressed syllables, and some fluent elders don't have them at all.

sally thomason said,

July 29, 2023 @ 3:07 pm

@Victor Mair: Visible caution came only in the comments, not in the post itself, where it would have been appropriate. (The list of "selected readings" didn't really offset the post's tone.)

Victor Mair said,

July 29, 2023 @ 3:27 pm

I'm a firm believer in the fruitfulness of mutual discussion and discovery, and would not like to foreclose either.

Chris Button said,

July 29, 2023 @ 6:32 pm

@ Sally Thomason

When you get that far back in the mouth, the distinction between fricative and approximant/resonant doesn't really matter much though. The IPA doesn't even bother to posit separate symbols from the uvular and beyond. And even at the velar point of articulation, the voiced velar approximant ɰ (as distinct from the fricative ɣ) was only added in the 1970s.

So, I have no issue with h3 patterning like a resonant. The voicelessness of h2 could be a problem, but surely it can just be put down to a (colored) epenthetic schwa insertion as a default feature of syllabification?

I suppose h1 is still a challenge if it is treated as a glottal. I suppose that would be a good argument for the alternative interpretation of it as /h/.

Surely that's entirely reasonable? A pharyngeal glide being effectively a non-syllabic back /a/ vowel in the same way a /j/ glide corresponds with /i/, etc.

Once we're this far back, is there a solid phonetic explanation as to why a pharyngeal would be more likely to vocalize than a uvular?

Georg Orlandi said,

July 29, 2023 @ 8:46 pm

While this study is better than other phylolinguistic studies from the Max-Planck Institute, I still feel it doesn't bring much new to the table. It's just a rearrangement of the same old stuff, like those cognate lists. Honestly, I wonder if those lists can ever be really "improved" at all.

The paper's conclusions mostly confirm what we already know, and sometimes they even seem to support conflicting or different theories. I bet it's because the authors are afraid of being too radical and getting rejected by the reviewers.

Here's a thought-provoking idea: I'll start taking these new phylolinguistic methods seriously when they actually produce results that go beyond the state-of-the-art. Like, tell me where the PIE homeland is, and surprise me by saying it's in, say, Portugal or something!

Just wanted to share my two cents on this.

Cheers

An anonymous said,

July 29, 2023 @ 10:04 pm

Hello @Sally Thomason

>At least two of them do, however, resemble resonant pharyngeal consonants in modern Salishan languages like Selis-Ql'ispe (a.k.a. Montana Salish), where the plain pharyngeal (not labialized, not glottalized) phoneme retracts vowels and vocalizes into [a] when not next to a vowel phoneme, and the labialized nonglottalized pharyngeal phoneme retracts vowels and vocalizes into [o] when not next to a vowel phoneme.

Can you give your references?

I'm particularly interested in the "vocalizes" part.

Chris Buckey said,

July 29, 2023 @ 11:20 pm

I'm currently re-reading Anthony's "The Horse, The Wheel, and Language" and while I'm not a linguist, good grief does this "new insight" seem, to put it politely, based on some extremely tenuous foundations.

Simon Greenhill said,

July 30, 2023 @ 3:18 am

Colleagues,

It makes me despair for the state of linguistics if we need to flag controversial studies a priori. All I can ask is that you read the article in question and make your own minds up. I'm happy for you to disagree with us but at least make it an informed disagreement.

Simon.

Dragos said,

July 30, 2023 @ 8:06 am

The Latin/Romance tree is still a mess. Latin separated from Romance in 500 BC? Latin dead at the end of the Republic? First Romance language, Romanian, diverged around AD 150? Can't believe that 20 years later, their trees fail on relatively known language divergences.

Matt said,

July 30, 2023 @ 10:10 am

@Dragos, well, we are talking about inferring placing divergence dates on a tree, which is an abstraction of continuous variation, using about 140 cognates that may change at rates which they believe smooth out over the long term but can be variable at any given time. There is a degree to which things won't precisely resolve to exact times that exactly match conventional estimates, which estimates let's not forget, cannot be inferred from any other kind of linguistic information with any certainty (e.g. not sound changes or changes in morphology) and are only estimated from having dateable documents. There are limits to the resolution of the data, but what they're trying to resolve (the higher order parts of the tree and the general depth of branches) are dates within which a few hundred years is not a significant factor.

Moreover the paper linked above by Garrett Jones relates to the questions of whether Classical Latin should be considered a direct ancestor of Romance, or a shallowly diverged sibling.

Sean M said,

July 30, 2023 @ 12:08 pm

Matt: it seems like having Latin separate from Romance around 500 BCE would not be an error of "a few hundred years" but "about a thousand years"!

I don't see a paper by a Garrett Jones above.

Dragos said,

July 30, 2023 @ 12:42 pm

@Matt, thank you for your response. I guess that my actual point is that as long as these models fail to explain the data that we can verify, how can they be trusted on data that we cannot?

One of the studies published 10-15 years ago (I apologize, I don't remember now which one) included a small program to generate trees. I tried it with a tiny database of Romance languages and noticed that I could get different topologies and root dates (from ca. 3000 BP onwards) depending on the constraints and cognates I coded (lexical or morphological). I know the models improved meanwhile, but I would still like to see the robustness of the model on known data, before moving to more ambitious questions.

On the divergence of Romance, regardless whether Classical Latin is considered ancestor of the Romance subgroup or not, the putative origin of the latter is estimated before 500 BC, which is a huge difference for a group of languages that diverged relatively recently. For example, on the divergence of the first Romance language, they wrote: "The median estimate for the start of divergence to the Romanian sub-lineage is 363 CE (rather than 162 CE in our main analysis), although the Roman Empire had already definitively withdrawn south of the Danube under Aurelian in the early 270s CE." So apparently they were aware of these dates, but found them unproblematic. The controversial "homeland" of Romanian aside, there is virtually no romanist or classicist regarding the language of that part of the Empire to be anything but Latin in 162 CE, and arguably 363 CE is also too early a date to speak about Romance languages.

sally thomason said,

July 30, 2023 @ 12:48 pm

@An Anonymous: The only reference for Montana Salish specifically is "Phonetic Structures of Montana Salish", by Flemming, Ladefoged, & Thomason, Journal of Phonetics 36/3:465-491 (2008); it has a section on pharyngeals and their phonetic realizations in different environments. Nicola Bessell has done quite a bit of work on pharyngeals and other post-velars in Salishan languages more generally; the only reference I have at hand is her 1992 dissertation, Towards a phonetic and phonological typology of post-velar articulation (University of British Columbia). The only other consonants that undergo vocalization in Montana Salish are the glides /w w' y and y'/ (the glottalized ones vocalize to vowel + glottal stop), unlike PIE, where all the resonant consonants vocalized in vowel-less environments. Well, there's also Montana Salish /n/, which turns into [i] when it precedes an /s/ in the same word, provided the /n/ is not (part of) a prefix; but that alternation doesn't have any obvious phonetic motivation.

@Chris Button: I'm not a phonetician, so I can't answer your question with any authority; all I can say is that I've never heard of a uvular fricative vocalizing, but of course like any other linguist I have intuitions about such things that are necessarily limited by my personal experience. Some languages have very loud uvular fricatives — actually uvular trills, some or most of the time — like the German in a word like Buch or Bach; by contrast, the Montana Salish dorsal fricatives, both velar and uvular, are quite lax — I could imagine them vocalizing in appropriate environments. But they don't seem to.

Jim said,

July 31, 2023 @ 3:02 am

In simple layman terms, does the graph in the paper indicate that from the living languages Albanian appeared before Armenian and these before Greek, and so on?

Matt said,

July 31, 2023 @ 4:45 am

@Sean M:

1) Their sampled classical Latin is dated to 50 BCE, so from the point of view of that sample date it is a few hundred years (or 450 precisely; the sort of time frames on which English dialects diverge).

2) Papers linked within the tweet he links to, although the paper is not by him.

Sean M said,

July 31, 2023 @ 12:53 pm

Matt: I will see if one of the alternative front ends to twitter works today. It would have been much clearer to say "the paper by Garrett Jones in the Twitter thread by Andrew Garrett."

If the model places the divergence of Classical and Vulgar Latin to 500 BCE, that is an error of 1000 to 1400 years, which just happens to be 450 years before their sample of Classical Latin. If they had picked Latin from the first century CE, the error would have been the same but the distance from the sample would have changed.

Sean M said,

July 31, 2023 @ 1:40 pm

Matt: The twitter thread by A. Garrett cites Chang et al. "Ancestry-constrained phylogenetic analysis supports the Indo-European steppe hypothesis"; David Goldstein "Divergence-time estimation in Indo-European: The case of Latin"; Heggarty et al. "Language trees with sampled ancestors support a hybrid model for the origin of Indo-European languages." From the abstract, the second argues that Vulgar Latin and Classical Latin most likely began to diverge after 300 CE.

Could you please provide a citation to the paper by Garrett Jones which you mean?

ohwilleke said,

July 31, 2023 @ 3:59 pm

This paper, like previous papers by Quentin Atkinson who is a New Zealand colleague of Gray, is wrong for essentially the same reasons.

The case for an old PIE is driven by the divergence of the Anatolian languages from other IE languages which is used to argue that it is basal and old. But, the archaeological and historical data support an appearance of Indo-Europeans in Anatolia around 2000 BCE, not 8000 BCE, and the absence of steppe genetics also supports that conclusion. The interpretation given that these absences of steppe impact are due to a primary dispersal from Anatolia and only a secondary dispersal from the steppe don't hold water. Nothing in the linguistic landscape of Anatolia at the time of its presumed migration to the Steppe is remotely similar to PIE.

The basic problem with Gray's model is that it is underestimating the amount of language change that is due to language contact and overestimating the amount of language change that is due to random linguistic mutation at a fixed rate over time. The Anatolian languages in Anatolia were much more different from the substrate languages encountered by other IE languages and the existing population of pre-Anatolian language speakers was greater and more prosperous so they weren't swept away wholesale by IE invader languages to the same degree without having an impact. Also, most of the other languages displaced by IE languages (in Europe, at least) had a common origin in the language of Western Anatolian first farmers, so the contract effects would have been more similar among them, perhaps even looking like shared contract effects with similar languages had a common PIE origin instead, than the strong substrate effects from a more divergent language encountered by Anatolian language speakers.

Dragos said,

August 1, 2023 @ 12:20 am

@Sean M: Goldstein's paper does not make that claim: "The central feature of this hypothesis is that it embraces variation within Latin. In contrast to the sibling hypothesis, it does not assign low-register or low-sociolect features to another taxon. Instead

the variation is a property of a single language, Latin tout court" But I have doubts about that date. Since languages are represented by word sets, a convincing estimate should produce younger dates (as in Chang et al. 2015). For example, the lexical changes in Romanian, the daughter language which is modeled to have diverged first, are mostly dated to after ca. AD 800 (loanwords from Slavic, Hungarian, Turkish)

Matt said,

August 1, 2023 @ 12:49 am

@Sean M: the context of the comment to the Dragos was about the sibling model for Latin, and refers to papers "linked by" Jones "above" and since the first link in his OP in that thread is simply Heggarty's 2023 paper currently under discussion is the first link, so thought it be relatively obvious, but if it is useful, it is the second link.

Matt said,

August 1, 2023 @ 1:12 am

@Sean M:

"If the model places the divergence of Classical and Vulgar Latin to 500 BCE, that is an error of 1000 to 1400 years, which just happens to be 450 years before their sample of Classical Latin. If they had picked Latin from the first century CE, the error would have been the same but the distance from the sample would have changed."

It's very difficult to tell what would happen if they'd applied a later sample date on Latin as a furthe constraint to their tree, say a few hundred years.

It's possible that the divergence time between sampled Latin and the proto-Romance ancestor would still be a few hundred years, but this would all be shifted later in time.

Assuming that the tree had an unchanged divergence date, then why stop there, as we could also say that if they'd sampled Medieval Latin, we could add a good thousand years onto the error we're claiming they made! But would that be a substantial criticism of the issues that the paper is looking to address (the higher order tree structure, from the point of view of the lexicon, and the root divergence date)?

Matt said,

August 1, 2023 @ 1:36 am

@Dragos: The paper by Goldstein itself is not favourable to the sibling hypothesis but cites that: "Of the three hypotheses in Figure 3, the sibling hypothesis enjoys by far the most support (e.g., Väänänen 1983:483, Hall 1950:19, Coseriu 1954:29, Hall 1974:14, Mańczak 1977:13, Vallejo 2012:458)." (including the "Sampled Ancestor" hypothesis), and further that "Despite wide acceptance, empirical support for the sibling hypothesis has been difficult to come by, as even some of its advocates acknowledge (Murray et al. 1994:371).", albeit that: "It is essential to bear in mind, however, that these studies use coalescent tree models, which do not allow sampled ancestors, so Latin was bound a priori to be a sibling to Proto-Romance. In other words, the sibling hypothesis is an assumption of these studies, not a result. By contrast, in the fossilized birth-death analyses of Rama 2018, Latin could have been sampled as an ancestor but was not."

Where Goldstein's paper is not supportive of a sibling hypothesis, the most immediately persuasive item I could identify was that: "The complementary pattern, whereby an archaism is shared between Romance and an Indo-European language other than Latin appears not to exist. This apparent absence is important because the sibling hypothesis allows for precisely this possibility.". Although this does not indicate that there are an absence of ancestral cognates within Italic for instance that the Romance ancestor has which Latin does not, so this might be a relevant point to investigate further with Heggarty et al's dataset.

Anyway, the point is not to bear down strongly in favour of the sibling hypothesis, but to add some context about what the state of the field looked like from this paper, and avoid a presentation where the concept of Latin as a diverged sibling to the ancestor of Romance is unknown within the field outside these Bayesian phylogenetics papers. (Of course, if this is a misrepresentation of Goldstein's paper in any way, happy to have Andrew or someone with a deeper linguistic knowledge set and knowledge of the paper hard charge in here to say so!).

Also I believe that identified loanwords in their dataset are discarded from the algorithm used to build trees, in their models, so although these may be present in a branch, the dates presented are essentially estimated "divergence date for this language, excl. the influence of loans".

Matt said,

August 1, 2023 @ 2:32 am

@Dragos and Sean M, also of interest may be that the authors discuss in their supplement the effect of building a "sampled ancestor" tree (along the lines of Chang et al 2015), under section supplementary 7.7. I'll quote a couple of excerpts from this:

"Our first ancestry constraint analysis (SA7a) nonetheless tests the effects of applying" (the constraint that written Classical Latin is directly ancestral to all spoken Romance languages) "The result is to shift the median root date for Indo- European earlier by 331 years (4.08%), but only along with simultaneously distorting the chronology for the divergence of Romance. The first splits to Romanian and Sardinian are pushed significantly later than in our main (unconstrained) analysis, and now too late to be compatible with historical and linguistic indications. The median estimate for the start of divergence to the Romanian sub-lineage is 363 CE (rather than 162 CE in our main analysis), although the Roman Empire had already definitively withdrawn south of the Danube under Aurelian in the early 270s CE. On Sardinian, Chang and colleagues themselves recognize (on p. 266 of (12)) that “the Sardinian and non- Sardinian vowel systems had diverged structurally” already in “Latin regional texts c. 250 CE” (citing Adams (31)). They nonetheless constrain Classical Latin as if a direct ancestor, which delays that split until 517 CE (relative to our main analysis median estimate of 399 CE)."

"The third ancestry constraint analysis, SA7c, speculatively constrained every one of the 27 IE-CoR languages that could be even remotely conceivable as a (near-)direct ancestor — even though our main analysis finds no real support for almost all of them. Even under these extreme and invalid assumptions, the median root date for Indo- European still shifted by only 506 years (6.23 %), and earlier, i.e. further from the Steppe hypothesis chronology"

In their current dataset, the imposition of sampled ancestor constraints (ones the authors view as implausible, not to imply an authority) does not have any major effects on the big picture of the overall date time of the deeper splits. I believe (from memory anyway!) that Chang's paper raised the issue that in the IELex cognate database, treating sampled possible ancestors as non-ancestral led to pushing deeper dates back due to expanding the chronology to allow for additional time between the "sampled ancestor" and the estimated ancestor. This does not seem to be the case here, on this cleaned up database, and that if anything adding these constraints pushes the overall root dates earlier, at least judging by the above and the methodology these authors have used for this.

At any rate this seems to support the contention by Paul Heggarty (https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/full/10.1146/annurev-linguistics-011619-030507) here that the fact that Chang 2015 found that adding date constraints changed root date times significantly was an effect of data quality in IELex.

Matt said,

August 1, 2023 @ 2:48 am

@ohwilleke: "The case for an old PIE is driven by the divergence of the Anatolian languages from other IE languages which is used to argue that it is basal and old."

Looking at the trees here, I don't know if this is strictly the case.

In the main tree presented by Heggarty et al in this paper divergence Anatolian (and Tocharian in this model, unusually forming a clade!) separate from the "core IE languages" (usually argued to be certain to descend from a steppe ancestor) only ~700 years prior to their breakup.

Although the tree structure is different (with Anatolian+Tocharian *not* a clade), this is not a lot different as even Grey and Atkinson estimated between the splitting off of Antolian and the break of "core IE".

So what's going on with these trees is that, rather than having a "short chronology" for non-Anatolian with a very deep Anatolian branching, they just having a very long chronology overall, with Anatolian being not especially deeply diverged.

The inclusion of Anatolian then does seemingly not really too much influence the mean root date (although perhaps the authors should try this model).

If we are to argue that contact and change pushes the early dates much deeper than we would estimate from a predominantly modern language sample with less of this sort of thing (a fair potential criticism), then this seems to indicate that is pervasive within most or all branches of the tree, rather than concentrated in Anatolian.

Dragos said,

August 1, 2023 @ 9:21 am

@Matt:

I know the sibling hypothesis was once popular, but I wonder if that's still the case today. J. N. Adams argued strongly and convincingly against it. Goldstein also used one his examples to make a point: "The example of ‘mouth’ illustrates the failure of the sibling hypothesis. (…) Os is attested across a range of styles and registers, including colloquial sources, so it cannot be assigned exclusively to Classical Latin. In the same vein, bucca in the sense of ‘mouth’ is used by Cicero (Att. 1.12.4) and the emperor Augustus (ap. Suet. Aug. 76.2). Moreover, Romanian bucă (< bucca) preserves the older meaning ‘cheek’, so bucca could not have exclusively meant ‘mouth’ in Vulgar Latin or Proto-Romance. In sum, the evidence does not support the view that os was the high-register word for ‘mouth’ and bucca its low-register counterpart."

I also doubt that the remarks of Heggarty et al about some dates being too late hold much water. On the contrary, these dates might be too early for the data they use. They mention vowel systems in Latin regional texts as reference, but IE-CoR does not contain phonological characters. Which lexical innovation in Sardinian (or in Romanian) can be securely dated that early?

Sean M said,

August 1, 2023 @ 10:08 am

Matt: I am still trying to figure out how to get access to the full article (probably need to visit campus), but generally in an iterated process (such as dating a series of splits in the Indo-European language family) errors compound, often exponentially. If they misdate a split about 1000 years ago by about 1000 years, that does not give much confidence in their ability to date a split 5,000 to 8,000 years ago within a thousand years!

ohwilleke has a good point that while the first farmers to arrive in Europe probably spread a language family or a handful of families (doesn't the archaeogenetics support this?) these languages were probably among those marginalized and eventually eliminated by first the Corded Ware Culture expansion and then Greek and Roman imperialism

Matt said,

August 1, 2023 @ 12:22 pm

@Sean M: Yep absolutely, whether 1000 or 450, you're that could be the case if there's evidence of substantial, systematic compound of specifically earlier divergence dates among nodes, by large enough margins. Randomly distributed error in both directions of the same magnitude around the true date, though, would be expected to even out (some shifted slightly earlier and some later) though rather than compound (and both would be diluted by estimates which were as correct as we have any reason to guess). So e.g. if the branch length of common ancestor of Latin+Romance to the common ancestor of Romance is too long, because that period was actually shorter and much more lexically productive for the time length than estimated by the rest of the dataset, then that should even out if, e.g. other branches are set too short (they were actually longer in time and more lexically conservative for that time, than is estimated).

In theory, that should be the benefit of using large sets of data here I guess. Provided that the sampled data is representative of the unsampled period in rates of change, which I think there is reasonable grounds to have a bit of skepticism about, despite the wide set of languages.

So I think it would be a stronger case for compound that if there was systematic error (or whatever size) in a particular direction, across multiple subtrees. I think previous analyses like Chang et al's argued for exactly this sort of systematic pushing of earlier divergence dates by the effect of illusory excessively deep divergences sampled ancient varieties from their likely common ancestor with sampled recent varieties (I think Andrew Garrett used the term "jogging" for this at one point). The authors think they've dealt with this particular error for the instances that existed, and also similar errors involving recent languages, by their new dataset, but possibly there is some other systematic error in this one, and it would await more analysis of this paper to really say.

@Dragos, I guess it's possible that the sibling hypothesis enjoys less current/recent support than it might seem from the paper by Goldstein, I'm not knowledgable enough to even venture a guess. Probably you would have to do some literature review or canvas a set of relevant experts to test it?

Re; early Sardinian / Romanian lexical differentiation, directly attested as to inferred from a model: I think what you might then call for then, to try and show evidence of systematic divergence (rather than some particular selected terms which might be anything), if you sought to refine the dates further, is applying the same methodologies by adding datapoints of early divergent corpus of provincial latin… But then isn't a problem and cause for lack of consensus exactly that this corpus doesn't exist in enough plenty (or is it more of a problem that can be solved)?

ohwilleke said,

August 3, 2023 @ 2:01 pm

Moore generally, the rate at which languages evolve is far from an exact science as illustrated by the 1000 years error in the divergence of the Romance languages from Latin that is historically well attested.

What the authors should have done was to take the quite precise dates and geographic locations of changes in archaeological cultures, of ancient DNA data, and of historical attestation of languages all arrived at by methods not reasonable subject to numerically large inaccuracies and used those dates as high confidence Bayesian priors to constrain the parameters and form of the language evolution model. The whole point of Bayesian statistics is to not waste the data you already have as you evaluate new data, that way that you must when using frequentist statistics.

Other evidence gives us a very solid foundation that should have been the skeleton into wish the linguistic muscle and flesh should have been fitted. This other "hard" evidence (archaeology, ancient DNA and history) gives us considerable confidence in another chronology, one in which: The Tocharian split from other Indo-European languages around 3300 BCE. The Balto-Slavic and Indo-Iranian branches split around 3000 BCE to 2500 BCE. The Indo-Aryan languages arrived in South Asia from Central Asia sometime after the collapse of the Harappan culture ca. 2500 BCE to 1500 BCE, and start to diverge centuries after that. The European branches of the Indo-European languages begin to differentiate sometime during and after the spread of the Corded Ware Culture in Europe between 3500 and 2500 BCE. The Indo-European languages reach the Italian Peninsula around 2200 BCE. The Anatolian languages arrived in Anatolia around 2200 BCE to 2000 BCE, and that Mycenaean Greek arrived in the Aegean at around the same time. The Romance languages split from a common Latin origin around 500 CE. With the right parameters for random evolution over time, and substrate influences in the former Harappan, former Hattic, and former European Neolithic farmer domains, these ought to fairly tightly constraint the parameters and form of the linguistic evolution model and produce a result that makes more sense and is not so obviously flawed relative to the Bayesian priors we have from all other sources.

There are ambiguities in the phylogenetic tree, like Armenian that may reflect the shortcomings of a simple tree-like branching model for languages that have geographic neighbors that are highly diverged from each other and for which we have only relatively recent written attestation. But working from what we know with greater certainty to the parameters of language evolution which we know with lesser certainty is a good start, instead of letting the uncertain model parameters overwhelm the data about which we are much more certain.

The narrative of this paper calls for all sorts of phenomena like deep linguistic substructure in geographically compact, archaeologically uniform, and genetically homogeneous populations that don't have good known precedents that are similar, while taking away clear motivates of climate driven societal collapses, heavy demic introgression into existing populations to the points of mass replacement of Neolithic men in some places (a quantifiable factor that could be used to estimate substrate impacts), and technologies like horses and wheels and moderately advanced metallurgy, with clear well demonstrated similar historical precedents.

A model that can be used to support a sensible narrative that integrates all of the available evidence isn't a good model.

ohwilleke said,

August 3, 2023 @ 2:03 pm

*** A model that canNOT be used to support a sensible narrative that integrates all of the available evidence isn't a good model. ***

ohwilleke said,

August 4, 2023 @ 1:18 pm

A comment on the paper seen elsewhere:

"They have a systematic error of branch scaling which elongates branches with excessive borrowing (which is especially typical for Indic languages) or have limited knowledge of synonym pairs representing meanings in their dataset (which is common for many ancient languages). Both problems stem from the same computational simplification. Namely, they treat each cognate responsible for the given meaning as an independent binary value (present or absent) while in reality, presence or absence of synonyms for a given meaning are negatively correlated.

Basically in the languages where coevolving synonyms are well attested, a gain or a loss of a synonym will generally have a change value of 1 (1,1 -> 1,0 or vice versa). But in languages with external borrowing or with unknown synonym pairs, any such change would count as 2 (loss of the original cognate plus gain of a new one).

This scaling problem would have inferred even older split dates have it not been artificially limited by setting the upper bound for the age at 10,000 years. In one of the sensitivity analyses they removed this upper bound and ended up with estimates as old as 11 kya.

There is also an important linguistic consideration for the Northern route and against the South Caucasus urheimat, and it is borrowings from IE to neighboring languages. The oldest layer of IE-derived words in the Finno-Ugric languages is thought to be related to proto-Iranian and dated to ~Sintashta epoch in the Ural Mountains. Conversely, Gamkrelidze and Ivanov assembled a great collection of potentially IE-derived words in Kartvelian and Semitic languages but nothing there is convincingly older than Mitanni age."

Chris Button said,

August 5, 2023 @ 6:22 am

Pondering on this some more, If we have /k/ /kʷ/ /kʲ/, then perhaps having /k/ surface phonetically as [q] makes good sense if we treat it in terms of its features as /kᵃ̯/ (the non-syllabic sign is supposed to go under the "a"). I don't see why that would necessitate treating /kʲ/ as /k/ as "the uvular hypothesis" seems to propose. The idea that phonemic/k/ surfaces as [q] would then allow us to have /x/ (h2) and /ɣ/ (h3) as phonetically [χ] and [ʁ] without gaps in the phonological system.

Chris Button said,

August 5, 2023 @ 11:38 am

(Admittedly a rather Edwin Pulleyblank-esque formulation with the pharyngeal glide)

Victor Mair said,

August 6, 2023 @ 9:24 pm

From Paul Heggarty:

This article appeared in Science on 27th July 2023:

"Language trees with sampled ancestors support a hybrid model for the origin of Indo-European languages"

To download a pdf copy free, please use this free system that Science allows, with just three clicks:

1. Go to https://iecor.clld.org.

2. You will land at the homepage for the IE‑CoR language database, where at the top you will see the link to click to download the article.

3. That will take you to a free-to-read view of the article on Science. To download, click on the red pdf icon to the right, just under the article title.

You may also be interested in:

— The supplement to the Science article, almost 100 pages of details on all aspects.

— The language data, which can be freely explored at IE‑CoR,

e.g. patterns of related words in the meaning FIRE, as one example (out of 170).

https://iecor.clld.org/parameters/fire#3/41.56/35.28

— A support page for the article, with further resources and information:

https://paulheggarty.info/indoeuropean.

Victor Mair said,

August 7, 2023 @ 6:23 am

From Peter Kupfer, an authority on the history of wine:

In connection with PIE the wheel and horse have been mentioned frequently, why not wine?

Is it a coincidence that the cultivation of grape wine has the same source in the Caucasus?

Sean M said,

August 14, 2023 @ 1:32 am

Victor Mair: I am told that there is scholarship about PIE, Sumerian, and Semitic words for "wine" and which might come from which, but I can't cite any research on the question. The Electronic Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary s.v. "ĝeštin" suggests M. Powell, Origins and Ancient History of Wine 100-101; 103; 105; 105-114 (they seem to mean the 1995 book by Patrick E. McGovern et al., second edition 2003)

David Marjanović said,

August 21, 2023 @ 4:02 pm

A long discussion on the paper, including but by no means limited to all (!!!) my thoughts on it, started here and continued till August 6th. Much of it is about the tip-dating method; I'm reasonably familiar with it from biology, so I was able to contribute.

News to me – the plain series is so much rarer than both the palatalized and the labialized series that many have tried to question its existence. (It's not surprising, however, if you assume that vowel frontness & roundedness got blamed on the consonants during a vowel megamerger.)

I'm afraid this is at least fifty years out of date. All three "laryngeals" behave like *s in terms of where they can go in a syllable, including but not limited to being unable to be the nucleus.

No, a few hundred at most. The Latin in the database is Strictly Classical Latin, the written register of Caesar and Cicero and nothing else. This was already not identical to how normal people normally spoke (indeed Cicero's private letters are a bit different), and the latter is ancestral to Proto-Romance, while the former is not. 500 BCE is certainly extreme, but 100 BCE would seem fine to me.

This is all explained in detail in the actual paper, the so-called supplementary material. In Nature, Science and PNAS, the "paper" is just an extended abstract, and the actual paper is "supplementary".

All that is in open access.

David Marjanović said,

August 21, 2023 @ 5:46 pm

May I ask what happened to my comment?

David Marjanović said,

August 22, 2023 @ 10:29 am

Oh, sorry, apparently it just landed in moderation for a few hours.

Goueznou said,

September 5, 2023 @ 4:18 pm

I was confused for several days by the mentions by "Matt" and "Sean M" of a Garrett Jones when apparently Andrew Garrett was who "Matt" originally meant. It would be nice if people could admit to their typos.