Old Chinese onsets and the calendrical signs

« previous post | next post »

[This is a guest post by Chris Button]

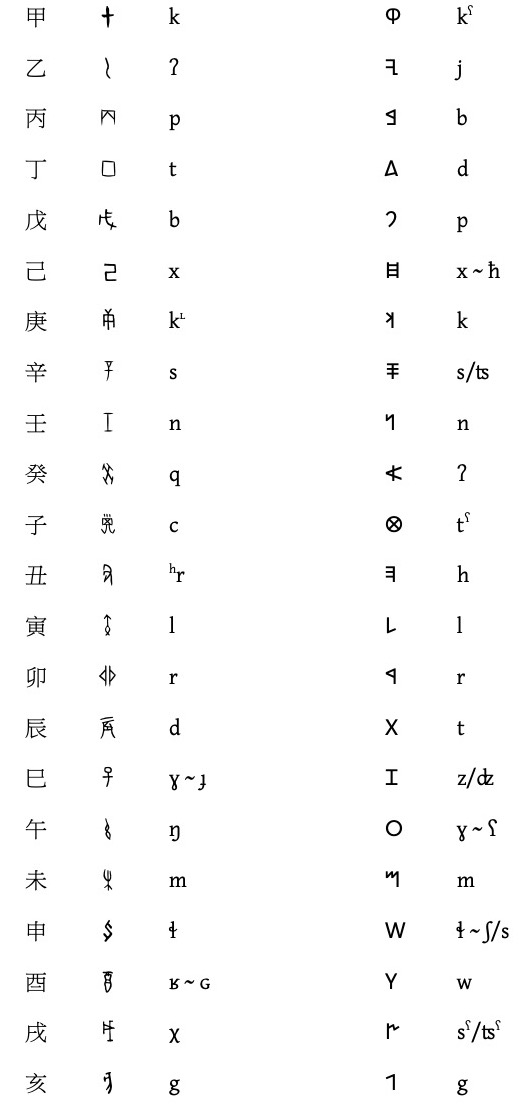

Below are my reconstructed Old Chinese onsets lined up with the 22 "tiangan dizhi"* calendrical signs ("ganzhi"). To be absolutely clear, the reconstructions are based on evidence unrelated to the ganzhi. It's just a very interesting coincidence that they happen to line up so well. Pulleyblank was clearly onto something! I'm not including the Middle Chinese reflexes here, but I have worked them out in detail and can send that over if there is interest. Two things not noted in the list are that an s- prefix caused aspiration (e.g., st- > tʰ–) and that the voiced stops alternated with prenasalized forms (e.g. b ~ ᵐb).

[*VHM: "ten heavenly stems and twelve earthly branches"]

甲 k

乙 ʔ

丙 p

丁 t

戊 b

己 x

庚 kʟ

辛 s

壬 n

癸 q

子 c

丑 hr

寅 l

卯 r

辰 d

巳 ɣ ~ ɟ

午 ŋ

未 m

申 ɬ

酉 ʁ ~ ɢ

戌 χ

亥 g

Separately, I'm a little reluctant to share any of my highly speculative correspondences between the ganzhi and the 22 symbols of the Phoenician alphabet because I don't want the correspondences to be used as grounds for criticizing my reconstructed onsets, which should stand or fall based on how well they account for the phonology of Old Chinese and its Middle Chinese reflexes. Having said that, I can't help but see correspondences in sound and form, so figure I may as well share what I have and hope that readers take the proposal in the spirit it's intended.

Representation in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA)

Selected readings

"The Alphabet and the Zodiac" (12/6/22)

"On the Origins of the Alphabet: The Cycle of Emmer Wheat and Seed/Word Selection within the Proto-Sinaitic/Phoenician/

"'The world's oldest in-use writing system'?" (5/12/12) — Ugaritic is mentioned in a couple of important comments by Gene Buckley

"Sally Rooney bucket hat; Hittite, Ugaritic, and the alphabet" (1/17/22) — "…an old project of mine that I [VHM] began around four decades ago, in which I compared the sounds and shapes of the Ugaritic / Phoenician alphabet and the Chinese tiāngān dìzhī 天干地支 ('heavenly stems' and 'earthly branches') that are used for calendrical, ordering, and other purposes. A regular Language Log reader, Chris Button, and I have often discussed the uncanny similarities between the two sets of symbols. At one time, Chris's PhD adviser, Edwin Pulleyblank, entertained similar ideas, calling the stems and branches 'phonograms', and Chris himself has recently come up with a good comparison of the two sets. I even published a brief article focusing on one pair of symbols, (Ugaratic >) Phoenician b / and Chinese bǐng 丙 of the heavenly stems and have an unpublished three hundred page book manuscript on the subject that I've kept in a strong box for the last three decades and more." Needless to say, since I have not been able to publish my own correspondences all these decades, I'm pleased that Chris has made this post and brought this important subject out into the light in a way that will contribute to further constructive debate.

Victor Mair said,

January 12, 2023 @ 9:58 pm

If you cannot see all of the diacritics and special characters on your browser in the first list, go to the second list, which was imported from a pdf.

Taylor, Philip said,

January 13, 2023 @ 5:37 am

It would be really helpful for non-specialists such as myself, Chris, if the tables (and especially the second table) could have column headings added.

Chris Button said,

January 13, 2023 @ 6:27 am

The column on the left is the same as the one in the body of the post but with the oracle-bone inscriptional forms of the calendrical signs included down the middle (the tilde separates allophones that tended to diverge in their Middle Chinese reflexes)

The column on the right is the Phoenician alphabet with their phonological values based on reconstructions by others since I am no expert in that regard (the variations after slashes are based on lack of clarity: the variations after tildes are based on earlier forms that are supposed to have merged)

Taylor, Philip said,

January 13, 2023 @ 7:45 am

Many thanks, Chris — much appreciated.

Chris Button said,

January 13, 2023 @ 8:17 am

Re. Phoenician in my comment above, I should have said "reconstructions with tildes" not "reconstructions after tildes"

David Marjanović said,

January 13, 2023 @ 10:08 am

A velar fricative and a palatal plosive?

Jim Unger said,

January 13, 2023 @ 10:32 am

The links between individual early Chinese characters and Phoenician letters shown above are apparently based on one-to-one graphic resemblances. The order of the Phoenician letters in the Phoenician abjad is certainly not that of the 10 stems in their traditional order followed by the 12 branches in theirs, or vice versa. Is there a persuasive theory about how the orders of these series were established? I don't know of any.

J.W. Brewer said,

January 13, 2023 @ 11:40 am

This is no doubt a quite naive question because this is not an area I know much about, but when I look at the various tables in the wikipedia article on "Reconstructions of Old Chinese," all the proposals seem to have significantly more than 22 different onsets. For example, Pulleyblank seems to have 36 and Baxter (at least in an earlier iteration of his approach) to have 37.

Does Chris Button's proposal group some similar-sounding ones together in a way that gets the total number down to 22 (a lumper v. splitter sort of issue?), or is his claim just that a subset of 22 (out of some larger total number) of the onsets can be matched up to the calendrical signs?

Victor Mair said,

January 13, 2023 @ 11:52 am

@David Marjanović:

ɣ ~ ɟ

A velar fricative and a palatal plosive?

—————–

VHM: To see what's missing from the boxes, that's the 7th item up from the bottom on the second list, the one with 5 columns.

pamela said,

January 13, 2023 @ 12:59 pm

fascinating. i don't know anything at all of the technicalities but will spend some time pouring over this. thanks!

Jonathan Smith said,

January 13, 2023 @ 3:26 pm

@Jim Unger, etc.

As much as I despise hyping my own melons, here are some shares for anyone interested in ideas on the (indigenous) origins of the Stems and Branches that appear in books and journals as opposed to blogposts and lockboxes. Pankenier's (2011) idea goes back at least to 2009 and is the inspiration for my work such as it is from back in the day.

Pankenier 2011

Smith 2011

Smith 2012

Smith 2019

Re the post — Chris you must really cite Pulleyblank explicitly, at least 1979 and 1991, re gan-zhi "phonograms" — yours is the *exact* same (bad) idea and resembles esp. his 1991 in a great many particulars.

Re: "at one time […] Pulleyblank […] entertained similar ideas" — well, he never abandoned the above idea AFAIK. Rather he abandoned the idea of a further connection to the Phoenician alphabet or similar, judging in a moment of clarity that "remarkable as some of the similarities seem to be, they probably are a matter of coincidence and […] it is best to proceed on that assumption rather than to speculate further about possible common origins. Much is unknown about the origins of the alphabet and even more about the beginnings of writing in China, but there seems to be little advantage to either side in connecting the two problems." (1979: 37)

Chris you seem to have changed some 1/3 of your "Ganzhi-Phoenician" connections over just the last few months my friend… my you find your way to Pulleyblank's position above sooner rather than later…

Chris Button said,

January 13, 2023 @ 7:01 pm

Wow, lots of comments. I'll post some responses to the more substantive ones later on. Just one for now:

@ Jonathan Smith

I have? Even though I've never shared them publicly? I haven't actually made such changes, but how would you know even if I had? Weird …

Perhaps you are confusing things with the couple of comments I've made on LLog in the past regarding the reconstruction of the Old Chinese onsets (separate from any putative Phoenician correspondences)?

But even then, the reconstructions of the onsets here are by and large the same as the ones there!

Perhaps you didn't see the note in the o.p. that the list here keep things simple by leaving out the aspiration of onsets caused by an *s- prefix and the allophonic pre-nasalization of voiced stops?

I don't think you quite took this post "in the spirit it's intended."

Chris Button said,

January 13, 2023 @ 7:12 pm

Turns out I have shared ideas for the Phoenician correspondences in a comment responding to the third selected reading in the o.p.

Yet, aside from a rejigging of 己, 巳 and 午, they are identical!

Jonathan Smith said,

January 13, 2023 @ 8:06 pm

Chris you emailed me your "best comparisons from the Phoenician alphabet with […] reconstructed onsets for the ganzhi and their graphic forms" like a year ago. pdf named "ganzhi-phoenician"? author "chris"?

Button 2021 > Button 2023

戊: 2021 = mēm > 2023 = pē

己: 2021 = zayin > 2023 = ḥēt

癸: 2021 = ʿayin > 2023 = ʾālep

丑: 2021 = ʾālep > 2023 = he

巳: 2021 = he > 2023 = zayin

午: 2021 = ḥēt > 2023 = ʿayin

未: 2021 = pē > 2023 = mēm

7/22 = .318

I replied in part that "you would generate entirely different [graphic] matches via say a web survey on the matter"… I could have added "or by 'rejigging' it for another year or so"

Chris you know this crap has been done over and over and over, and at the end of the day 22 indeed equals 22.

Chris Button said,

January 13, 2023 @ 9:15 pm

@ Jonathan Smith

So by “last few months,” you mean “year and a half”, and you’re referring to a private note I sent you with the comment: “Figured I’d give it a shot, maybe there’s something in it after all.” And in spite of all that, and the highly speculative nature of it it all, it’s still roughly 70% consistent with what I’ve outlined here that I hesitatingly have made decided to make public.

To be clear, I’m wed to the idea of the ganzhi as onsets for which the independent evidence is incredibly strong since they happen to line up rather than being forced. This Phoenician thing is just something that seems to me possibly to have some legs, but has no bearing on my reconstruction of Old Chinese.

Might I suggest some objectivity, and indeed “taking it in the spirit it’s intended”, rather than taking it as a dismissal of your own publications on the origin of the ganzhi?

Chris Button said,

January 13, 2023 @ 10:32 pm

@ Jim Unger

Rather, the links are based on proposed graphic resemblances and sound correspondences

I don't know of any either, but I'm glad they don't correspond here because that would just be too coincidental, wouldn't it? Just think of the implications there.

Chris Button said,

January 13, 2023 @ 11:06 pm

@ J. W. Brewer

Good question.

As I commented to Jonathan Smith above, I have not included aspiration from an s- prefix and allophonic pre-nasalization of voiced obstruents in the chart. All told, I reconstruct 39 Old Chinese onsets if you count clusters with s- and allophones.

Having said that, my approach to reconstruction is rather more dynamic than other approaches and based more on how a living language would work.

Just to focus on the two points above in that regard …

The Middle Chinese that was borrowed as go-on readings into Japanese had pre-nasalized obstruents. It's usually something only noted by scholars of Old Japanese (and Pulleyblank!) since the pre-nasalized forms did not become the prestige/standard forms that influenced later varieties of Chinese. That doesn't necessarily mean that Old Chinese had pre-nasalization, but the phonetic purpose of using pre-nasalization to preserve voicing of obstruents that would otherwise want to be voiceless (because they aren't sonorants) is still a valid principle. I don't buy the suggestion by some academics that pre-nasalization in Old Chinese came from an an unspecified voicing nasal "N-" prefix (whatever that means). To me it seems more likely that the nasalization was an articulatory side effect rather than the cause. Pulleyblank's proposal for a non-syllabic vocalic on-glide seems more reasonable in that regard. The pre-nasalized forms then gave different reflexes in Middle Chinese from the plain forms.

Regarding s- prefixation, you'll see that I have alternations like /x/ versus /χ/ above. While not unknown, that's going to be a relatively tough one to distinguish phonetically! Throw in forms like /sk/ giving aspirated /kʰ/ and /sq/ giving /qʰ/, and you're asking an individual speaker to distinguish quite a lot. In living languages, cases like /kʰ/ and /x/ tend to overlap based on dialects/idiolects. What seems to have happened is that /sk/ gave /kʰ/ for some and /x/ for others, and Middle Chinese reflexes sometime reflect one and sometimes the other.

Chris Button said,

January 13, 2023 @ 11:17 pm

Sorry I should have said Kan-on instead of go-on for the Japanese loans.

Also, regarding pre-nasalization of obstruents in Japanese, I should add that they evolved in Middle Chinese out of nasals. So, for example, /m/ becomes /ᵐb/ via hardening in onset position (I think I recall there are similar cases in the evolution of Min dialects of Chinese, but I might be mistaken). That has no bearing on the /b/ ~ /ᵐb/ alternations that I am proposing for Old Chinese (where I actually follow a Mon-Khmer style evolution of Old Chinese /ᵐb/ evolving to /m/), other than to point out that the variants could co-exist.

Chris Button said,

January 13, 2023 @ 11:44 pm

@David Marjanović:

I assume you're asking how they could exist in variation? It's not that strange from an articulatory perspective, although it also brings to mind something I have been wrestling with regarding the palatal onsets in general.

The idea that uvular /q/, velar /k/ and palatal /c/ could be distinguished as such is not unheard of, but the palatal /c/ would presumably more likely shift to something like the affricate/ts/ for differentiation. The lack of a nasal palatal /ɲ/ is interesting in that regard.

An affricate /ts/ is most likely the source of /c/ (that would then account for the distributional gap regarding the missing nasal /ɲ/). Since Old Chinese had a palatal /c/ coda (resulting from palatalization of a -k coda and also the palatalization of a -t coda in certain environments), its seems reasonable to assume that /ts/ would have shifted to /c/ in onset position too. A similar case may be observed in Old Burmese where the same letter that is used for a palatal /c/ coda is usually treated as an affricate /ts/ in onset position, although it then vacillated with /c/ before medial -j- as /tsj/ before converging)

Returning to the voiced counterpart /ɟ/ of /c/, that would then originally be an affricate /dz/. However, /dz/ and /ɣ/ are not as easy to confuse as /ɟ/ and /ɣ/ except for the notion that the fricative articulation of /dz/ could have made the articulation /ɟ/ verge toward that of the typologically rather rare voiced palatal fricative /ʝ/, which would then be very close to /ɣ/.

Why does any of this matter? Well aside from accounting for various reconstructions of Old Chinese syllables, there is the notable case in the Ganzhi where the original graphic form for 巳 (/ɣ/ ~ /ɟ/) was actually 子 /c/, and there is the well-known confusion of 巳 (/ɣ/ ~ /ɟ/) with 己 (/x/) in characters with them as phonetics. From an articulatory perspective, maintaining voicing on a fricative onset is taxing, and so the voiced fricative /ɣ/ for 巳 could be confused with the voiceless fricative /x/ for 己, and the voiced palatal stop /ɟ/ (verging on a fricative /ʝ/) could be confused with the voiceless palatal stop /c/ for 子.

Chris Button said,

January 13, 2023 @ 11:52 pm

Incidentally, the pre-nasalized voiced palatal stop /ᶮɟ/ in cases like 二 (Early Middle Chinese *ɲiʰ from Old Chinese *ᶮɟǝːjs) "two" accounts for how it can be phonetic in a word like 次 (EMC *ʦʰiʰ from OC *scǝːjs) "subsequent" because they both originally had palatal /ɟ/,/c/ (or rather affricate /dz/, /ts/) onsets.

Chris Button said,

January 14, 2023 @ 12:03 am

@ pamela

I'm glad you think so. Please take the Phoenician correspondences for what they are: highly speculative. However, looking at them lined up with the ganzhi like that, I can't help but see some tantalizing graphic similarities.

One thing that is interesting, is that the Phoenician forms often almost look like simplified forms of the ganzhi. I sort of would have expected it to be the other way round. I just wish there was some more evidence to marshal (and that I knew more about the Phoenician side of things).

Victor Mair said,

January 14, 2023 @ 9:50 am

@Chris Button

"…the Phoenician forms often almost look like simplified forms of the ganzhi. I sort of would have expected it to be the other way round."

Unless their common point of derivation were somewhere in the middle, about which Chris Beckwith might have something interesting to say.

J.W. Brewer said,

January 14, 2023 @ 4:25 pm

@Victor Mair, re "common point of derivation" being "somewhere in the middle" you are perhaps not considering a sufficiently wide range of "highly speculative" possibilities. Consider the perhaps highly speculative scenario proposed by the noted Scottish scholar D. P. Leitch:

"Knowing her fate

Atlantis sent out ships to all corners of the Earth

On board were the Twelve

The poet, the physician, the farmer, the scientist, the magician

And the other so-called Gods of our legends …"

One of the unnamed additional seven who made up the Twelve could well have been the scribe …

Victor Mair said,

January 15, 2023 @ 6:31 am

@J.W. Brewer:

First you'd have to believe in the existence of Atlantis, then you'd have to have some concrete evidence for where it was, what it was like, and so forth.

Chris Button said,

January 15, 2023 @ 10:05 am

Early Middle Chinese reflexes of Old Chinese onsets

The EMC reflexes follow Pulleyblank

Philip Anderson said,

January 15, 2023 @ 4:51 pm

I don’t think concrete evidence is required when merely producing a highly speculative scenario.

Chris Button said,

January 15, 2023 @ 5:15 pm

@ Philip Anderson

Two separate things going on here:

The onset proposal is not speculative in the slightest and supported with "concrete evidence" (or at least it accounts for the phonology)

The idea of a connection with Phoenician is highly speculative and lacks concrete evidence.

J.W. Brewer said,

January 15, 2023 @ 7:29 pm

The thing about 39 onsets v. 22 onsets as different (equally legitimate in different contexts) ways of grouping the same underlying data reminds me, of course (although maybe not everyone else free-associates the way I do …), of the Old Testament. The "narrow" canon of the Old Testament used by most Protestant Christians (excluding the various additional ancient texts variously called apocrypha, anagignoskomena, or "deuterocanonical books") is traditionally divided into 39 books. The canon of the Tanakh recognized by Judaism (since at least late Antiquity) has exactly the same textual content, but is instead traditionally divided into 24 books. The Jewish count combines e.g. what Anglophone Protestants call "1 Kings" and "2 Kings" into a single book (plus several other two-into-one combos), and combines all twelve "Minor Prophets" into a single "Book of the Twelve."

While no doubt some sort of edifying symbolism can be (and probably has been) ascribed to both the number 39 and the number 24 in this context, what is interesting for present purposes is that one can find both Jewish and Christian sources in earlier centuries (latest one I happen to know about is I think from the 8th century A.D. but my knowledge is likely to be incomplete) grouping the same set of texts into 22 books (by employing two more two-into-one combinations that the 39-into-24 grouping does), which was *obviously* parallel to the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet, and thus, in the view of its advocates, providential because it obviously could not have been a coincidence. I have my own theory about why the 24-book approach beat out the 22-book approach within Judaism (i.e. what other desiderata in taxonomic methodology successfully overrode the symbolic appeal of the number 22), but that's even farther afield from Old Chinese phonology and its written representation(s).

Chris Button said,

January 15, 2023 @ 11:58 pm

@ J. W. Brewer

It’s interesting you mention the number 22 and its variations, One of the things that dissuaded Pulleyblank was the realization that there were more than 22 “letters” in the ancestors of Phoenician (some of that is reflected in the variant phonological values in the list above, such as ɬ merging with ʃ / s ).

Lucas Christopoulos said,

January 16, 2023 @ 2:56 am

These look even more like Linear A (1800-1450 BC) ?

Lucas Christopoulos said,

January 16, 2023 @ 7:34 am

I think that there is also Twenty-two defined stems forms on the Phaistos disc as a calendar measure.

Chris Button said,

January 16, 2023 @ 12:55 pm

I'm not sure about that. Perhaps I'm wanting to see things in the Phoenician symbols. I'd be curious if other readers here even see where I'm going with some of the correlations. Please bear in mind, I've tried to match shape and sound at the same time.

On a separate note regarding my reconstruction of Old Chinese onsets, one area where I differ from some popular reconstructions (and indeed Pulleyblank to a degree) is that I don't reconstruct complex systems of affixational morphology, which personally I've always found rather forced. Instead, the onsets themselves account for the phonetic series and any etymological relationships between the words they represent.

Chris Button said,

January 17, 2023 @ 7:44 pm

Despite some consternation around the idea that I might have switched some possible Phoenician correspondences around (!) from a previous attempt (see the third "selected reading" in the o.p.), it goes without saying that some correlations with the ganzhi fit better in terms of sound and form than others.

So 丙, 丁, 申, 辛 are near slam dunks, while cases like 己, 巳 and 午 are less so.

Looking at my earlier post on the matter, I compared 午 with Phoenician /x ~ ħ/ instead of /ɣ ~ ʕ/ because the Phoenician form apparently may have derived from what looks like some twisted thread or twine, much like the original form of 午 /ŋ/. Unfortunately there is no velar nasal in Phoenician, so correlations in sound remain somewhat challenging beyond going with something "guttural".

That would then make Phoenician /ɣ ~ ʕ/ a good correlate with 巳 /ɣ ~ ɟ/ instead of /z, ʣ/ if the focus is on the round "head" of the original form of 巳.

However, correlating 己 /x/ with Phoenician /z, ʣ/ instead of /x ~ ħ/ does become somewhat challenging then in terms of sound.

In short, forms and sounds shift over distance and time. It is unsurprising that this also happened here (just look at the oracle-bone forms of the ganzhi and the modern forms, or the Middle Chinese reflexes of the Old Chinese onsets). Some more rejigging will likely be needed for less solid correlations like 己, 巳 and 午. In particular, it's upsetting that 壬 /n/ shows no correlation in sound with Phoenician /z, ʣ/ since their forms are practically identical. That is also the case with 甲 /k/ and Phoenician /t/.

It would be great if some experts in Phoenician could chime in with some thoughts. I am well-versed in matters of Old Chinese phonology and oracle-bone inscriptions, but my knowledge of Phoenician amounts to basically just what is including in this LLog post.

Chris Button said,

January 17, 2023 @ 7:45 pm

Chris Button said,

January 20, 2023 @ 10:53 am

Actually the proposed Phoenician correspondence (the circle with cross) with 子 does compare favorably with the proposed Phoenician correspondence (the circle) with 巳 in the above. So, if we go with the twine for 午, then the above layout (the one I posted earlier to LLog in a comment to the third selected reading in the o.p.) is probably the most promising for now.

Also, if we look at the Middle Chinese reflex of 戌 χ- in certain syllable types and its proposed association with Phoenician sˤ/tsˤ, then the correlation of 己 x- with z/dz- becomes less problematic.

That’s my best bet for now (and only what … one-sixth or one-seventh deviance from what I privately communicated earlier…?). I reserve the right to further tweak …

David Marjanović said,

January 21, 2023 @ 4:02 pm

It is, that's why I asked – but [ɣ ~ ʝ] is trivial, so thank you.

I would guess the Phoenician letters were interpreted as simplified/handwritten forms of already existing Chinese characters when they arrived in China…

Chris Button said,

January 21, 2023 @ 7:11 pm

Well it isn’t so much when I caveat it with everything that I outlined, but I had anticipated the comment.

It’s really about a coronal fricative articulation of [dz] and a dorsal stop articulation of [ɟ]. Then take the fricative and dorsal components together.

The real challenge is what symbol to use for the reconstructed forms that encapsulates the detail without raising questions on how such alternations could occur.

Any thoughts on that matter are very welcome!

Interesting idea.

Chris Button said,

January 21, 2023 @ 9:47 pm

On that last point, worth bearing in mind is the following quote from Pulleyblank (1991) cited in the Pankenier (2011) article mentioned above:

“The curious thing about these twenty-two signs is that neither the graphs nor the names attached to them have any separate meaning. Their meaning is simply the order in which they occur in the series to which they belong. It is true that a few of these characters are also used to write other homophonous words, but these are a small minority and such words have no apparent relation to the cyclical signs as such.”

Chris Button said,

January 21, 2023 @ 10:49 pm

And back to the voiced palatal, I suppose I’m talking about something like the affricate [ɟʝ] that Spanish /ʝ/ surfaces as in onset position.

In Old Burmese, a distinction can be made between ts- and tsj-, which merge as -c in coda position. I suppose here the ɟʝ- would effectively be ɟj- (the same way the prenasalized palatal stop would effectively be nj-), and that the vacillation of dz- and dzj-would be effectively that of ɟ- and ɟʝ-/ɟj-

The variation would then probably be between and

The challenge comes with a following -j- glide. So dzj- or ɟj- works but ɟʝj- is too much!

Chris Button said,

January 21, 2023 @ 10:51 pm

(Please ignore the garbled last sentence at the bottom)

Chris Button said,

January 22, 2023 @ 8:16 am

Appreciate I'm just sharing a stream of consciousness now, but for anyone still reading/caring …

I think this might be the best approach:

子 c- [ʦ-]

巳 ɰ- [ɣ], ɟ [ʣ ~ ʝ]

I want to go with c- rather than ts- in onset position to keep the number of phonemes down since -c is [c] in coda position.

The situation is similar to ɰ- which as an onset is [ɣ] (albeit still verging on approximant) but as a coda is [ɰ].

Chris Button said,

January 22, 2023 @ 8:56 am

Or better still for its simplicity:

子 c [ʦ]

巳 ɣ ~ ʝ [ʣ]

Chris Button said,

January 25, 2023 @ 11:07 pm

I’m going with the above for now.

One thing I didn’t mention is that I actually originally had 巳 ɣ ~ ʝ, but asked Victor to change ʝ to ɟ at the last minute since I needed a stop articulation to account for the association with 子 c, the Middle Chinese dz- affricate reflex, and the evidence of a pre-nasalized form.

I think 子 c [ʦ] and 巳 ɣ ~ ʝ [ʣ] nicely handles that while also accounting for the lack of a pure nasal counterpart ɲ on the grounds that original ts became conflated with phonemic c because of its emergence in coda position from palatalized k and t.

==============================

Final comment from VHM:

Judging from the vigorous discussion on this post and the cutting edge quality of the debate, plus the impressive level of participants engaged in it, I think we may say that it is on blogs such as this one that noteworthy research and discoveries are taking place.

We can be especially grateful to Chris Button for not only releasing his Old Sinitic and Middle Sinitic reconstructions of the 22 ganzhi, but also for revealing his tentative matching of them with the 22 letters of the Phoenician alphabet

As for my own correspondences, I decided three decades ago never to reveal them until I could present them in a full-dress historical, archeological, and linguistic monograph, because the nature of my proposals requires a complete reconsideration of the overall lineaments of Eurasian civilization during the Bronze Age.