WU2WEI2: Do Nothing

« previous post | next post »

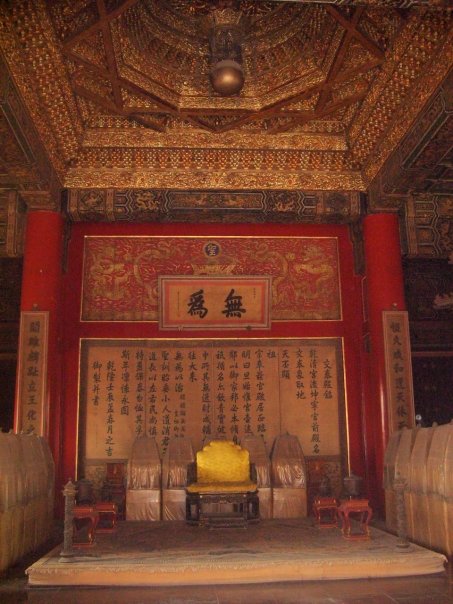

The following photograph was taken by Matt Marcucci in the throne room of the Forbidden City in Beijing. The two large characters on the plaque over the throne constitute the famous dictum of the Taoists: WU2WEI2. This is usually translated as "inaction" or "non-action," but more highly nuanced and fanciful translations such as "nonpurposeful action," "effortless doing," etc. are also to be found.

A curious, contradictory aspect of this Taoist Golden Rule was pointed out by the great 20th-century Chinese author, Lu Xun (1881-1936), who wrote the following in chapter 3 of his Han wenxue shi gangyao (An Outline of Chinese Literary History): "Lao Zi's words are inconsistent. He warned against prolixity, yet from time to time he gave vent to indignant words; he valued non-action, yet wished to rule all under heaven."

The grammarians argue over whether this is an injunction ("do nothing") or a negative declarative sentence ("there is no action"). It is normally rendered in English as a noun. Regardless of the part of speech, WU2WEI2 has had an enormous impact on Chinese thought for the past two millennia and more.

In the Afterword to my Bantam translation of the Tao Te Ching / Dao De Jing, I pointed out a number of Sanskrit terms (e.g., AKRTA [non-action], AKARMA [inaction], NAISKARMYA [freedom from action or actionlessness], KARMANAM ANARAMBHAN [noncommencement of action] — diacriticals omitted here), especially numerous in the Bhagavad Gita, that mean essentially the same thing as WU2WEI2. The Indian notions, while equally subtle and elusive, are quite different in their moral implications. Whereas the Taoist concept is both ethical and socio-political, the Hindu complex of ideas is metaphysical and existential.

pfc said,

March 10, 2009 @ 7:51 pm

But from such a small source, without specific context, who's surprised there have been multiple interpretations throughout the centuries? I've heard the phrase expressed as "knowing when to act, and when not to act." No matter the history and original intent, that particular meaning – a consideration of something akin to the "negative space" of modern art – is surely one worth considering.

It's an impressive picture, too. Thanks to Matt for sharing it.

Nathan Myers said,

March 10, 2009 @ 8:44 pm

Another nuanced, or perhaps noiranced, interpretation: "Nothing doing".

dr pepper said,

March 10, 2009 @ 9:18 pm

"Hang loose"

"Let go, let God"

"Easy does it"

rootlesscosmo said,

March 10, 2009 @ 9:33 pm

Gary Snyder gave the English equivalent as "no fuss."

D. Wilson said,

March 10, 2009 @ 9:43 pm

Apparently approximated by "laissez-faire" in some contexts.

Note that "wu" is on the right, "wei" on the left in the picture.

John Lawler said,

March 10, 2009 @ 10:55 pm

As some of the characters on The Wire are prone to say, "Ain't no thing".

Fluxor said,

March 10, 2009 @ 11:15 pm

As far as I know, 無為 means to refrain from action that goes against the natural laws of the universe. The nature laws of the universe is "The Way" or Tao/Dao/道.

Some have applied wu2wei2 to the open and free marketplace as this is the natural state of human affairs. Centralized economic planning is unnatural. Thus, "laissez-faire" is often the translation when used in this context.

peter said,

March 11, 2009 @ 1:11 am

Fluxor — If centralized economic planning is unnatural, why is it that this mode of organization is the one most commonly used internally by companies and organizations, including almost all the Fortune 500?

tgies said,

March 11, 2009 @ 1:40 am

Actually, that says "No Action" and the text that follows is the earliest Chinese translation of the Elvis Costello song by the same name.

[(myl) Some scholars also see an influence of the Frankie Goes to Hollywood song Relax: "When you want to go to it / Relax don't do it". ]

MattF said,

March 11, 2009 @ 7:04 am

OK Fluxor, I'm confused. At least in the modern world of today, you can't go against the natural laws of the universe. As in "Today, I think I'll violate Maxwell's Equations". Well, good luck with that…

Mark F. said,

March 11, 2009 @ 7:40 am

Did this phrase have no context in its early sources?

[(myl) You could read e.g. the entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy for some interpretation; or read the various translations of the original work, including Victor's.]

language hat said,

March 11, 2009 @ 8:33 am

From the Stanford Encyclopedia link myl provided:

The concept of wuwei, “nonaction,” serves to explain naturalness in practice. “Nonaction” is awkward, and some translators prefer “non-assertive action,” “non-coercive action” or “effortless action,” but it identifies wuwei as a technical term. It does not mean total inaction. Later Daoists may see a close connection between wuwei and techniques of spiritual cultivation — the practice of “sitting in forgetfulness” (zuowang) discussed in the Zhuangzi is often mentioned in this regard. In the Laozi, the concept seems to be used more broadly as a contrast against any form of action characterized especially by self-serving desire (e.g., chs. 3, 37).

Fluxor said,

March 11, 2009 @ 9:17 am

@peter: I believe those that apply the term wu2wei2 to economics is talking about macroeconomics — Adam Smith's invisible hand and all that. The claim is that deliberate interference in free and open markets will yield sub-optimal results, not unlike the philosophy of those that prefer small government and minimal government interference. This is in contrast to centralized planning like the USSR, for example.

@MattF: I don't think Laozi was talking about the laws of physics. His assertions are more metaphysical.

Mark Liberman said,

March 11, 2009 @ 9:59 am

The paragraph following the one that language hat quoted may also be helpful:

HeyTeach said,

March 11, 2009 @ 10:06 am

A truly free and open market system, free from government interference, will inevitably result in one person (or a few people) owning and controlling everything. The talk is all about competition and how great that is for the open market, but truly free enterprise is bad for competition, because the goal of truly free enterprise is to squash the competition. It's cutthroat and greedy.

That doesn't sound very wu2wei2 to me. I don't know that Lao Zi would have approved.

Mark Liberman said,

March 11, 2009 @ 10:23 am

A relevant section (48) from the Dao De Jing (in Mitchell's translation) is:

Another translation is here:

Victor's translation:

An extensive comparison of Chinese versions and translations is available here.

This reminds me of a story from my days at Bell Labs in the 1980s. The code base of AT&T's digital switches was over a million lines and growing, and the productivity of programmers was the usual 10-15 lines per day and shrinking. One of the project managers came to Murray Hill to ask the Unix research group for help in increasing programmer productivity. Brian Kernighan's response, in summary: "Instead of measuring programmers' productivity in terms of the number of lines of code they add, you should measure it in terms of the number of lines they remove."

Unfortunately, I believe that Daoist programming is much easier to practice in the context of a program designed and implemented by a few friends, than it is from the perspective of one coder among a thousand in an industrial-scale project.

Victor Mair said,

March 11, 2009 @ 10:39 am

I chuckled as I read each and every comment posted above. Whenever I make a post to Language Log, I never know what to expect from commenters. I must say, though, that almost invariably I find the responses to be intelligent and illuminating. What is really fun for me is when the discussion goes off on a brilliant tangent that was totally unanticipated. Participating in the moveable LL feast is both endlessly educational and entertaining.

peter said,

March 11, 2009 @ 10:56 am

Fluxor: My point is that the resource planning and allocation system used in the USSR is very similar to that used internally in large companies. That system, in companies such as AT&T (prior to its breakup in 1984) or in present-day GM or in the US Military, has no better label than "centralized economic planning", and it has many of the features one associates with the economy of the USSR – allocation by diktat, shadow or parallel markets, inefficiencies, shortages and misallocations, the creation of a "third class" (increased power to the groups responsible for the allocation), etc. It is perfectly possible to design internal market-based systems instead, as John Birt imposed on the BBC for example, using real or token money. Thus, anyone who contends that centralized economic planning is inferior to other modes of resource allocation surely has an obligation to explain why this mode exists and persists inside large organizations despite its claimed inferiority.

Randy Alexander said,

March 11, 2009 @ 12:05 pm

Let's look into the context a little more closely.

In the oldest (possibly not complete) copy of Dao De Jing, there are six instances of 无为.*

I'll give their traditional chapter numbers, and then Robert Henricks' translation of the Guodian Bamboo Slip version, and Victor Mair's translation of the slightly later Mawangdui Silk version. To save space, I've stripped out the line breaks (but you can usually see where they are with the capitalization). I've put the words that represent 无为 in italics. The order here follows the Guodian version.

—64 (part 2)

RH: Those who act on it ruin it, Those who hold on to it lose it. Therefore the sage does nothing, and as a result he has no disasters; He holds on to nothing, and as a result he loses nothing.

VM: Who acts, fails; Who grasps loses. For this reason, The sage does not act. Therefore, He does not fail.

—37

RH: The Way constantly takes no action.

VM: The Way is eternally nameless. [Note: here the Mawangdui version is different from the Guodian and the traditional later versions.]

—63

RH: Act without acting [为无为]; Serve without concern for affairs; Find flavor in what has no flavor.

VM: Act through nonaction, Handle affairs through noninterference, Taste what has no taste,

—02

RH: Therefore the sage abides in affairs that entail no action, And spreads the wordless teaching.

VM: For these reasons, The sage dwells in affairs of nonaction, carries out a doctrine without words.

—57

RH: I do nothing, and the people transform on their own;

VM: I take no action, yet the people transform themselves;

—48

RH: Those who [toil at] their studies increase day after day; Those who practice the Way, decrease day after day. They decrease and decrease, Until they reach the point where they do nothing at all. They do nothing, yet there is nothing left undone.

VM: The pursuit of learning results in daily increase, Hearing the Way leads to daily decrease. Decrease and again decrease, until you reach nonaction. Through nonaction, no action is left undone.

So we can see that 无为 generally means sitting back, letting go, and watching things unfold (realizing that one doesn't need to micromanage everything).

*I'm one of those guys who likes simplified characters. And anyway, in the two oldest versions of Dao De Jing, Guodian and Mawangdui, 無 was written as 亡 and 无, respectively.

John Cowan said,

March 11, 2009 @ 3:22 pm

Okay, okay, if people are going to quote translations, I'll quote my own:

48:

Seek knowledge every day,

you win.

Seek the Way every day,

you lose.

Lose and lose again,

until you reach hacklessness.

When you're hackless,

nothing is left unhacked.

World domination

is always achieved egolessly.

When you're ego-driven,

you're never able to dominate the world.

57:

Use justice to run a project.

Use surprise to run a company.

Use non-interference to achieve world domination.

By what do I know this is so, indeed?

By this:

When the world is full of

restrictions and prohibitions,

the people grow poorer.

When the companies have

many fast-talking lawyers,

the world grows more and more troubled.

When the geeks abound in

clever techniques,

abnormal things more and more occur.

When law and order becomes

more and more evident,

more robbers and thieves appear.

So the hacker says:

I do without doing,

and the people spontaneously transform themselves.

I prefer quiet,

and the people are spontaneously fair.

I don't interfere,

and the people are spontaneously wealthy.

I am not greedy,

and the people are spontaneously honest.

63:

Design without designing,

implement without implementing,

debug without debugging.

The great lessens (and the small grows);

the many become few (and the few become many).

Respond to ill-treatment

with the Power of the Unix Way.

Tackle difficult projects while they're easy;

manage big projects while they're small.

In this world,

difficult problems surely arise

from what is easy;

in this world,

big systems surely begin

in what is small.

Thus the hacker doesn't set big goals,

but can accomplish big results.

(Truly, frivolous promises lack sincerity.)

What's too easy surely has many difficulties.

Thus the hacker takes difficulties seriously,

and ultimately has no difficulties, indeed.

Nathan Myers said,

March 11, 2009 @ 5:27 pm

peter: It's no accident that corporations are organized like the former Soviet Union. However, the corporations didn't copy it from the Soviets. The Soviets, rather, copied it from (to be very precise) the Ford Motor Company. Lenin was a big admirer of FMC. We may find they will all come to much the same end, for much the same reasons. Anyway we can hope.

dr pepper said,

March 11, 2009 @ 7:24 pm

In the martial arts much is made of things happening without effort. If you have to hit hard, you're doing it wrong. Instead you should just let your fist float of its own accord to strike. And of course if your opponent attempts to dodge, they will fail, but if they simply let themselves not be in your path, you will miss.

Jack Collins said,

March 11, 2009 @ 8:07 pm

I once saw a sign in the back of a shop in Chinatown that said, "Do not beyond this point."

peter said,

March 12, 2009 @ 4:18 am

Nathan: Just to clarify: In referring to economic planning (centralized or otherwise), we are not talking about methods for the organization of work, such as the Fordism so admired by Lenin. Rather, we are talking about methods for the allocation of resources, a different, indeed orthogonal, issue.

language hat said,

March 12, 2009 @ 5:55 pm

A commenter on my post about this made the important point that the characters above the imperial throne would be followed by "the implicit érzhì 而治 'and rule' that completes the four-character phrase : wúwèi érzhì 無為而治 'Do nothing and rule', a quotation from the Analects of Confucius," which makes a lot more sense for a Confucian regime than a Laoist allusion.

Noetica said,

March 12, 2009 @ 10:17 pm

Cited above:

Niṣkāma karma is a notion central to the Bhagavad Gita. This is action (karma) without desire (kāma): action without attachment to the fruits of action.

The Gita counsels against both action with attachment and sheer inaction. Why shouldn't wu wei be aligned with this proscribed inaction? Perhaps it should; and perhaps the Gita and the Dao texts disagree fundamentally. But there is a reconciliation to be found when we reflect on who or what it is that is supposed to act, or to refrain from action, or indeed to be the hypostatised "owner" of desires. Certainly questions of personhood and separateness are at the core of the Gita, and they are presumably also addressed less explicitly in the Dao texts. Exactly what constitutes "the world" "being at peace" is also of interest. We can't analyse any salient concept from those texts without re-examining the others also.

Merri said,

March 13, 2009 @ 5:23 am

I agree with the interpretation of "letting things unfold", with possible translations as "no interference" or "no mingling".

marie-lucie said,

March 13, 2009 @ 11:16 am

No micro-management.

Bao Pu said,

March 13, 2009 @ 2:17 pm

Why is "wu" is on the right, "wei" on the left in the picture?

Fluxor said,

March 13, 2009 @ 9:45 pm

@Bao Pu: Because Chinese was traditionally written from top to bottom, then right to left. If the writing was strictly horizontal, it was still right to left traditionally. In mainland China, strictly horizontal writing reversed direction in the 50's. In Taiwan, it was the late 70's.

Bao Pu said,

March 14, 2009 @ 5:00 pm

Thanks Fluxor. I knew that when written vertically, it was right-to-left, but I have never seen it right-to-left when written horizontally. Do you know approximately when the Chinese wrote horizontally, right to left?

Good health,

Bao Pu

Fluxor said,

March 14, 2009 @ 6:11 pm

Bao Pu, traditionally, the Chinese only wrote right to left horizontally if it was impratical to write vertically. Horizontal banners, store signs, etc. are typical examples. In newspapers, captions that are placed underneath photos may be written horizontally across two or three lines. Otherwise, horizontal writing never really took off until the switch to left to right writing.

Aaron Davies said,

March 15, 2009 @ 12:32 am

and of course there's the tao of programming

Nigel Greenwood said,

March 15, 2009 @ 6:38 pm

"No wei!"

"Less is more."

Victor Mair said,

March 16, 2009 @ 11:37 am

I asked E. Bruce Brooks, author with E. Taeko Brooks of The Original Analects: Sayings of Confucius and His Successors (Columbia University Press, 1998), "How 'Confucian' is WUWEIERZHI 無為而治 ('to rule through inaction')? Although, as other commenters (see Language Hat above) have pointed out, it is in the Lunyu (Analects), but in what sort of stratum / context?" I should note that Bruce treats the Analects the same way modern text critical scholarship treats the Bible, namely, as an accretional text made up of different layers that reflect the intellectual debates among Confucius's successors that were going on at different times. Thus the Analects is seen as having evolved from around 479 BC to around 249 BC. The passage in question is dated by the Brookses to around 305 BC. Here is what Bruce says about it:

====

LY 15:5, c0305, written when the Analects was divesting itself of its own meditation tradition, but at the same time trying to save what of the DDJ line of goods could be assimilated to what it then thought was its residual governmental tradition. The piece is a summary and envoi to 15:1-2, in which the vanity of military effort to achieve good government is insisted on. The uncertainty of efforts to achieve good government is also insisted on. The common ground between the two, which is made explicit in 15:5, is equanimity of spirit. Somewhat as in MC 2A2, which is almost exactly contemporary with it, but on a grander historical panorama.

====

DDJ = Dao De Jing / Tao Te Ching

MC = Mencius (MENGZI)

ren said,

March 26, 2009 @ 10:11 am

Mr. Mair, I don't see where the contradictions that you mentioned are. Can you cite directly from the DDJ evidence to back you up? Quoting from Lu Xun's artistic license doens't make anyhing.

Your translation of "wuwei" is also inaccurate, to anyone who is familiar with classical Chinese.

And I would also liek you to explain how the Taoist concept is ethical and socio-political, and not metaphysical and existential.

Finally, I hope you can answer directly some of the queries this Indian poster has in this post: http://s6.zetaboards.com/man/single/?p=8004706&t=8538302

Shimon Edelman said,

June 12, 2009 @ 9:47 am

It's probably a bit late to post a comment in June on an entry from March, but I just came across these two items that seem relevant:

1. In a 1904 edition of Dao De Jing, (The Book of the Simple Way of Lao Tse, full text available through Google Books), there is a foreword by Walter Gorn Old, M.R.A.S., which includes the following statement: "There can be little doubt that any translation from the Chinese is capable of extreme flexibility and licence… This is due to… the entire absence of any rules of syntax" (p.19).

2. The author's introduction to Ask the Awakened by Wei Wu Wei expresses a similar belief regarding Chinese syntax: "It is our misfortune that Chinese pictograms are devoid of grammar and syntax, that most words have many meanings, and that only someone who has fully understood the meaning of the text could really be qualified to translate it".

I wonder how large is the grain of salt with which we should take translations from the Chinese made by people who, like Wei Wu Wei, believe that written Chinese has no grammar.