Corpora and the Second Amendment: “bear arms” (part 3) [UPDATED]

« previous post | next post »

[Part 1, Part 2.] An introduction and guide to this series of posts is available here. The corpus data can be downloaded here. Important: Use the "Download" button at the top right of the screen.

New URL for COFEA and COEME: https://lawcorpus.byu.edu.

From The Public Records of the Colony of Connecticut

From October, 1735, to October, 1743, Inclusive

—♦—

THIS WILL BE my final post about bear arms, and it will be followed by a post on the right of the people to … bear arms and another on keep and bear arms. These posts will directly address the linguistic issues that are most important in evaluating the Supreme Court's decision in District of Columbia v. Heller: how bear arms was ordinarily used in the America of the late 18th century, and how the right of the people, to keep and bear Arms was likely to have been understood.

As I’ve previously explained, the court held in Heller that at the time of the Framing, bear arms ordinarily meant ‘wear, bear, or carry … upon the person or in the clothing or in a pocket, for the purpose of being armed and ready for offensive or defensive action in a case of conflict with another person.’ In my last post, I discussed the uses of bear arms in the corpus that I thought were at least arguably consistent with that that meaning. Out of the 531 uses that I identified as being relevant, there were only 26 in that category—less than 5% of the total.

In this post I’ll discuss the other 95%.

As I’ll explain, I think that all of those uses would most likely have been understood as conveying the idiomatic sense relating to the military: ‘serve in the militia,’ ‘fight in a war,’ and so on.

That reading of the data shouldn’t be surprising, since it’s consistent with the views of those who have previously written about the corpus data, and also of people who looked at usage data before the corpora I’ve used were in existence. (For credit where credit is due, see the discussion at the end of this post). But if all I wanted to do in this post was to count up how often bear arms was used in a military sense, the post would be over by now.

What I’ve done in addition to that is to try to identify patterns of recurring usage and to organize the data on the basis of those patterns. That process yielded insights into the ways in which bear arms was used in late-18th century America, and those insights were in turn useful in trying to figure out how bear arms was most likely understood as it was used in the Second Amendment. However, the latter issue will have to wait until my next post. The focus here is on examining the range of ways in which bear arms was used.

MY GOALS in doing this series of posts go beyond looking at the linguistic issues raised by the Heller decision and the Second Amendment. In addition to doing that, I’ve tried to use the discussion of Heller and the Second Amendment as a vehicle for showing how corpus linguistics can be used in legal interpretation. I’ve done that mainly by showing what corpus analysis can do—for example, what kind of information it can it provide. I also want to give some idea of what the process of working with a corpus involves. So I hope you’ll indulge me while I say a few words about methodology, but if you’re not interested, you can skip ahead.

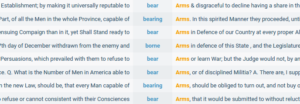

As I said in the previous post, I searched for all instances in which arms (as a noun) appeared within six words on either side of any form of bear (as a verb: bear, bears, bearing, bore, born, borne). The results were displayed in the form of a Key Word in Context (KWIC) concordance—essentially a spreadsheet in which each use responsive to the search appears on a single line, with the key word in one column and the context in separate columns on either side, as shown below.

This display format makes it possible to review the results quickly; the amount of context shown above, which is only portion of the actual display, is usually enough to allow at least a tentative decision about how each line should be categorized—a process known as coding. (If the context provided by the concordance isn’t enough, the amount of context shown can be expanded by clicking on the line.)

The corpus display is read-only, so the coding can’t be done online. Instead, the data has to be downloaded to a spreadsheet or database program. In my case, I downloaded it to a spreadsheet, to which I added a column that could be used for coding each line. In the image below, you can see the column that I used for coding (the third column), as well as the results of an early iteration of the coding process. (Note that by this stage in the process, I had filtered out lines that were duplicative or irrelevant, as described in my last post.)

In this excerpt, the coding for each line is an attempt to characterize the immediate context in which bear arms occurs: “able to bear,” “compel [to bear],” “liable to bear,” and so on. Sometimes the context is simply repeated more or less verbatim, as with “compel [to bear]” and “liable to bear.” Other times it involves a degree of generalization, as with the category “able to bear,” which covered uses that related to the ability to bear arms either positively (“able to bear arms” and “capable of bearing arms”) or negatively (“unfit for bearing”).

As you can see from even this short sample, repeated patterns of usage jump out at you: bear arms is used in ways having to do with the ability to bear arms, with compulsion or obligation to bear arms (“compel” and “liable to bear”), and religious objection to bearing arms (“scruple”). The KWIC format’s ability to reveal such patterns is one of the things that makes corpus linguistics such a powerful tool.

Identifying those patterns was essential to how I did my analysis, because for about three quarters of the corpus lines, it was the patterns that provided the basis for categorization. That will hopefully become clear from my discussion of the results.

(Before I turn to that discussion, I want to note that in some of the concordance lines that I’ve used here as examples, I’ve modernized some of the spelling and have cleaned up particularly intrusive OCR anomalies, based on looking at a copy of the source document that I was able to locate on the Web.)

THE FIRST CATEGORY OF USES that I’m going to talk about consists of a network of constructions relating, directly or indirectly, to there being a duty to bear arms. And the uses in that network can themselves be clustered into subcategories, the most important of which is made up of uses focusing directly on the duty to bear arms. These include (obviously) duty to bear arms, and also uses such as compel to bear arms, be liable [or obliged] to bear arms, and shall bear arms.

The other subcategories consist of uses that presuppose the existence of a duty to bear arms, and that focus on some relation or property or condition having to do with that duty. For example, there are uses such as exempted [or excused or released] from bearing arms, which concern exceptions to the general rule that bearing arms is obligatory.

In addition, there is a subcategory of uses focusing on objecting to bearing arms for religious reasons—conscientiously scrupulous of bearing arms, refuse to bear arms, etc. These uses are related to the notion of exemption from the duty to bear arms by the fact that having a religious objection to bearing arms can provide the basis for being exempted from the duty to bear arms. And of course, in the context of a society in which there is a general duty to bear arms, having a religious objection to bearing arms amounts to having an objection to complying with that duty.

These uses account for 121 concordance lines, and they can be found in sections 1a–1g (concordance lines 1–121) of the spreadsheet for bear arms.

As I’ll discuss in my next post, I think that this category—and in particular the central subcategory relating directly to the duty to bear arms—plays an important role in determining what bear arms would most likely have been understood to mean as it was used in the Second Amendment. Because of that, the discussion of this category will go into in some depth.

I’ll start with the uses at the center of the category: expressions such as compel to bear arms, be liable/obliged to bear arms, duty to bear arms, and shall bear arms. (Section 1a, Lines 1–38.)

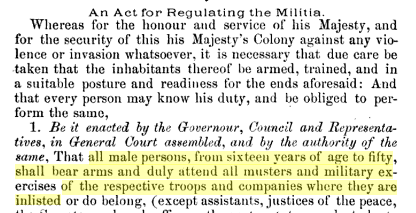

In interpreting those uses, the question obviously arises as to what obligation(s) existed in colonial, revolutionary, and post-revolutionary periods having to do with the bearing of arms (in any sense of the phrase). And for people who are familiar with the history of those times, the answer that first comes to mind is probably the duty to serve in the militia. With a few exceptions, all able-bodied white males who were within a specified range of ages (e.g., 16–50) were considered members of the militia and were required to perform the service that was required of militiamen. And in fact, in the New England colonies at least, the laws specifying who was required to serve in the militia referred to that obligation as a duty to “bear arms.” One such statute (from Connecticut) is captured in the image at the top of this post, and shows up in the corpus data:

(1) be it further enacted, by the authority aforesaid, that all male persons, from sixteen years of age to fifty, shall bear arms, and duly attend all musters, and military exercise of the respective troops and companies, where they are inlisted [Line 28; Google Books.]

There were similar statutes in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont:

(2) That all male persons from sixteen years of age to sixty, (other than such as are herein after excepted), shall bear arms, and duly attend all musters and military exercises of the respective troops and companies where they are listed . . . [MA, NH, VT.]

(3) [It] is Enacted and appointed, that all Male Persons Residing for the space of Three Months within this Colony from the Age of Sixteen, to the Age of Sixty Years, shall bear Arms in their Respective Train-bands or Companies whereto by Law they shall belong…. [RI.]

All five of these New England statutes were expressly identified as governing the militia, and in part for that reason, it makes sense to interpret these laws as using bear arms to mean ‘serve in the militia.’

I think that the same is true of the following uses, given that they occur in the context of references to various aspects of the militia.

(4) within this province for the space of three months, (slaves excepted) is hereby declared to be liable to bear arms in the regiment, troop, or companies, in this province, or some or one of them, according to the directions of this Act [Line 15; Source.]

(5) [From law prescribing the form for a judicial warrant:] Whereas A. B. a person enlfted, and liable to bear arms in the said company, for [as the case may be] is by us duly adjudged, that he the said A. B. has forfeited for the ofence aforesaid the sum of [Line 16.]

(6) [From an act separately incorporating part of the territory of the town of Sudbury into a new town called East Sudbury:] that the Town Stock of Arms and Ammunition be divided according to the Number of Persons that are obliged to bear Arms in said Town. [Line 20.]

(7) Every county in this ſtate, that has, or hereafter may have, two hundred and fifty men, and upwards, liable to bear arms, ſhall be formed into a battalion, and when they become too numerous for one battalion, they ſhall be formed [Line 34.]

(8) ORDERED, That Col. Powell [and others] be a Committee, to consider and report, the number of country, militia that ought to supply the place of the detachments to be discharged on the first day of March next, and in rotation, to do constant duty, in and near Charles-Town; also the most effectual means to oblige such of the inhabitants of Charles Town, as are liable to bear arms, and are absent, to return to town; also the best division of the country militia, into battalions, where such division is necessary; and also, such measures as may, in their opinion, be necessary to render the militia most serviceable to the public. [Line 31.]

The appropriate interpretation of the examples 9–11, below, is less certain. Although I think that bear arms is used in an idiomatic military sense in each example, it’s not entirely clear that it would have been understood to mean ‘serve in the militia’ rather than ‘fight in a war or battle.’ In fact, I’m undecided as to whether those are distinct senses. Given that the possibility of having to engage in hostilities is an inherent part of being in the militia, bear arms might have had only a single sense encompassing both types of uses, with one aspect or another being more prominent in a given context. (And more generally, bear in mind that the reality of how a given word or idiom is used is often messy, exhibiting a range of variation that can be difficult if not impossible to fully capture in any generalization about the meaning(s) that the expression can convey.)

(9) The alarm spread through the colonies, after the defeat of Braddock, was very great. Preparations to arm were every where made. In Pennsylvania , the prevalence of the quaker interest prevented the adoption of any system of defence, which would compel the citizens to bear arms. Franklin introduced into the assembly a bill for organizing a militia, by which every man was allowed to take arms or not, as to him should appear fit. The quakers, being thus left at liberty, suffered the bill to pass; for although their principles would not suffer them to fight, they had no objections to their neighbours fighting for them. [Line 36; includes material from the extended context.]

(10) Mr. Scott objected to the clause in [a proposed amendment to the Constitution,] “No person religiously scrupulous shall be compelled to bear arms”. He observed that if “this becomes part of the Constitution, such persons can neither he called upon for their services, nor can an equivalent be demanded; it is also attended with still further difficulties, for a militia can never be depended upon. [Line 22.]

(11) We know of no instance in which the Quakers have been compelled to bear arms, or do any thing which might strain their conscience [Line 29.]

Despite my agnosticism about whether bear arms had one military sense or two, in the following concordance lines, it seems pretty clearly to have been used to refer to participation in hostilities. However, (12) and (13) deal with the duty to bear arms as it existed in places other than America, and given the provenance of (14), it probably isn’t reliable evidence.

(12) the last, he distinguished also between the young and the old, that is to say, those who were obliged to bear arms, from those who were exempted from it on account of their age; a distinction which gave more frequent rise [Line 30; Rousseau.]

(13) on their laws and worship, their depriving them of the money they used to send to Jerusalem, forcing them to bear arms, and pay public duties out of their subsistence money, and all this contrary to common faith, and [Line 35; from translation of The whole genuine and complete works of Flavius Josephus.]

(14) profligate prostitution of common reason; the consciences of men are set at nought; and multitudes are compelled not only to bear arms, but also to swear subjection to an usurpation they abhor. [Line 33; from proclamation by Gen. Burgoyne, of the British army, in 1777 (quoted in A narrative of Colonel Ethan Allen’s captivity).]

In any event, although there is some uncertainty about precisely how best to characterize the meanings of uses such as those in (9)–(11), I don’t think that uncertainty extends to whether those uses convey a military-related sense as opposed to the sense endorsed by Heller or the “literal” sense ‘carry weapons.’ So, when I say that I think those uses convey a military-related meaning, and that the other uses in in (1)–(14) do as well, I don’t mean merely that those uses occurred in a military-related context. Rather, I’m making a judgment about how the authors intended what they wrote to be understood, and about how each use of bear arms was likely to have been understood by those who read it.

Although militia service involved physically carrying weapons, that wasn’t all that it involved. There were other obligations as well, such as attending musters; providing one’s own firearm, powder, and ammunition; and most importantly, fighting, as needed, in military actions. It seems more likely to me that when bear arms was used in connection with the duty to bear arms, it was intended and understood to denote the whole constellation of activities comprising bearing arms, and not just the action of carrying weapons. After all, those other aspects of militia service were, along with the social and political functions of the militia, presumably part of what made militia service socially significant, and therefore a recurrent topic of discussion.

At this juncture I need to address what some people might point to as evidence against the argument I’ve been making. In some of the colonies there were laws that required the physical carrying of weapons in certain situations—for example, when going to church or other public assemblies. So was it those laws that gave rise to what was thought of as the duty to bear arms? I think not.

To begin with, there’s reason to think that the duties these laws imposed were regarded as an aspect of militia service rather than as something separate from such service. Some of the laws explicitly imposed the duty on “such [people] as beare armes,” on “all men who are fittinge to bear arms,” or on those “liable to bear arms in the militia.” Others recited that the duty was being imposed “for the security and defense of this province from internal dangers and insurrections” or to “prevent or withstand such sudden assaults as may be made by Indeans”— interests that it was the role of the militia to protect.

In addition—and more important—the idea that these laws were regarded as imposing a duty to “bear arms” is at odds with how the laws were worded. As far as I’ve been able determine, none of the laws used the phrase bear arms in defining the duties that they imposed. Here is a sample of the language that these statutes did use:

(15) All men that are fitting to bear arms, shall bring their pieces to the church …. [Virginia 1631 & 1632.]

(16) [M]asters of every family shall bring with them to church on Sundays one fixed and serviceable gun with sufficient powder and shot …. [Virginia 1642.]

(17) Come to the publike assemblies with their muskets, or other peeces fit for servise, furnished with match, powder, & bullets, upon paine of 12d. for every default …. [Plymouth 1636/1637.]

(18) It is Ordered, that one person in every several howse wherein is any souldear or souldears, shall bring a musket, pystoll or some peece, with powder and shott to e[a]ch meeting.” [Connecticut 1643.]

(19) [N]oe man shall go two miles from the Towne unarmed, eyther with Gunn or Sword; and that none shall come to any public Meeting without his weapon. [Rhode Island 1639].

(20) [E]very male white inhabitant of this province … who is or shall be liable to bear arms in the milita either at common musters or times of alarm, and resorting, on any Sunday or other times, to any church, or other place of divine worship within the parish where such person shall reside, shall carry with him a gun, or a pair of pistols, in good order and fit for service, with at least six charges of gun powder and ball, and shall take the said gun or pistols with him to the pew or seat, where such person shall sit, remain, or be, within or about the said church or place of worship…. [Georgia 1770.]

Sources: Cramer, Lock, Stock, and Barrel: The Origins of American Gun Culture (2018) (link); Johnson et al., Firearms Law and the Second Amendment: Regulation, Rights, and Policy (2d ed. 2018) (link); Frasetto, “Firearms and Weapons Legislation up to the Early Twentieth Century” (link); Duke Law School Center for Firearms Law, Repository of Historical Gun Laws (link)

These examples are of course consistent with the corpus data, which includes only a handful of instances in which bear is used to denote literal carrying. And it is what would be expected given that (as I’ve previously explained) by a century or more before the framing of the Constitution, bear had been replaced by carry as the verb ordinarily used to denote the carrying of physical objects.

I’LL TURN NOW to the uses of bear arms that related to the duty to bear arms, but in which the relationship was indirect. I tend to think that the meaning that these uses were intended and understood to convey was in a sense dependent on what the duty to bear arms was understood to entail. It makes sense to think that the duty to bear arms provided a major part of the context in which the uses I’m about to discuss were used and understood.

This is most clearly seen as to uses such as exempt [or exemption] from bearing arms, as in (21)–(23):

(21) ſome preliminary conſiderations. The firſt is, that as military force is eſſential to every ſtate, no man is exempted from bearing arms for his country: all are bound; becauſe none can be bound, if every one be not bound. [Line 54.]

(22) Ministers should share the same protection of the law, that other men do, and no more. To proscribe them from seats of legislation, & c. is cruel. To indulge them with an exemption from taxes and bearing arms, is a tempting emolument. The law should be silent about them; protect them as citizens, (not as sacred officers) for the civil law knows no sacred, religious officers. [Line 56.]

(23) The militia in the ſeveral diſtricts have an annual meeting, and all males from the age of ſixteen to forty-five are muſtered, except the Friends, Tunkers, and Menoniſts, and thoſe of that religious deſcription, who are exempted from bearing arms [Line 57, with extended context.]

There can be no such thing as an exemption without a corresponding duty or obligation, just as there can be no such thing as a hole without some corresponding substance (literal or metaphoric) that marks out its boundaries. In fact, an exemption can be thought of as a hole in an obligation. This means that in uses such as (21)–(23), the meaning of bear arms depends entirely on the content and dimensions of the duty to bear arms, whatever that might be. On the assumption that the duty to bear arms is a duty to serve in the militia, then expressions such as exempt(ion) from bearing arms mean ‘exempt(ion) from serving in the militia.’ And in fact there is at least one line in the corpus in which the exemption afforded to conscientious objectors was explicitly described in such terms:

(24) That all those persons called Quakers, Menonists and Tunkers, and all other persons Conscientioully scrupulous of bearing arms, shall be excused from miltia duty, (except when called into actual service,) on the payment of two [Line 87; Source.]

A more complicated situation is presented by the next two subcategories of uses, which I’ll discuss together. (Sec. 1b, Lines 39–43; Sec. 1g, Lines 75–121.) In the first of these, bear arms occurs in the phrase refusing to bear arms, as in this example:

(25) I knew the people's minds were in a rage against such as, from any motive whatever, said or acted any thing tending to discountenance the war. I was sensible that refusing to pay the taxes, or to take the currency, would immediately be construed as a pointed opposition to the present war in particular, as even our refusing to bear arms was, notwithstanding our long and well known testimony against it. [Line 40, with extended context. Source.]

The second subcategory consists of 46 lines in which bear arms appears in expressions focusing on religious objections to bearing arms:

(26) The Committee therefore would submit it to the Wisdom of the House, whether, at this Time of general Distress and Danger, some Plan should not be devised to oblige the Assistance of every Member of the Community; but as there are some Persons, who, from their religious Principles, are scrupulous of the Lawfulness of bearing Arms, this Committee, from a tender Regard to the Consciences of such, would venture to propose that their Contributions to the common Cause should be pecuniary, and for that Purpose a Rate or Assessment be laid on their Estates equivalent to the Expence and Loss of Time incurred by the Associators. [Line 80, with extended context. Source.]

(27) that every man who receives a protection from and is a subject of any State (not being conscientiously scrupulous against bearing arms) should stand ready to defend the same against every hostile invasion, I do therefore, in behalf of the United [Line 84.]

(28) Mr. Burke said, no man was more in favor of an efficient and competent militia than he was, but the various exemptions contended for are so many that he conceived the consequences would be subversive of the whole plan […] I know, said he, it is the policy of the day to make the militia odious; but I hope such policy will not be adopted by this House. He was not, however, opposed to all exemptions; he would exempt the people called Quakers, and all persons religiously scrupulous of bearing arms, stage-drivers, and instructors of youth; but their pupils, the students in colleges and seminaries of learning, should not should not be exempt; youth is the proper time to acquire military knowledge. [Line 93, with extended context. Source.]

(29) tax upon certain classes of citizens; not being consonant with the principles of justice to make those conscientiously scrupulous of bearing arms pay for not acting against the voice of their conscience. This, he said, was called the land of liberty [Line 101.]

(30) That one fourth part of the militia in every colony, be selected for minute men, of such persons as are willing to enter into this necessary service, formed into companies and battalions, and their officers chosen and commissioned as aforesaid, to be ready on the shortest notice, to march to any place where their assistance may be required, for the defence of their own or a neighboring colony; and as these minute men may eventually be called to action before the whole body of the militia are sufficiently trained, it is recommended that a more particular and diligent attention be paid to their instruction in military discipline. [¶] That such of the minute men, as desire it, be relieved by new draughts as aforesaid, from the whole body of the Militia, once in four months. [¶] As there are some people, who, from religious principles, can not bear arms in any case, this Congress intend no violence to their consciences, but earnestly recommend it to them, to contribute liberally in this time of universal calamity, to the relief of their distressed brethren in the several colonies, and to do all other services to their oppressed Country, which they can consistently with their religious principles. [Line 102, with extended context. Source.]

In (25)–(30), the meaning of bear arms seems to me to depend to a certain extent on the meaning of the duty to bear arms, but more loosely than in the case of (21)–(23). While the concept of an exemption from taking some action presupposes the existence of a duty to take the action, the same isn’t true of the concept of refusing to take an action or having a religious objection to taking it. As a result, there’s no logical necessity for the meaning of bear arms in uses such as those in (25)–(30) to reflect the conception of bearing arms that is reflected in the duty to bear arms. But given the context in which bear arms appears in such uses, it seems likely that it would have been understood in a way that was consistent with that conception.

The existence of the duty to bear arms was an important aspect of that context. Explicit allusions to that duty, and to the notion of exemptions from that duty, can be seen in (25)–(27), while in (28)–(30) there are more or less explicit allusions to the exemption of those having religious objections to bearing arms, and those allusions presuppose the existence of a duty to bear arms. Something similar is at work in (25), but the fact that there was a duty to bear arms and that some people were exempt from it isn’t so much alluded to as lurking in the background, as something that is taken for granted.

In light of this, it makes sense to think that even though the meaning of bear arms in examples such as (25)–(31) wasn’t strictly dependent on the meaning of bear arms in the context of the duty to bear arms, that was probably how it was used and understood. Given the contextual evocation of the domain of mandatory militia service, understanding religious objections to bearing arms as being congruent with the duty would have been the cognitive path of least resistance.

However, the Supreme Court’s approach in Heller to expressions such as those I’ve been discussing was very different.

The court addressed the issue in responding to Justice Stevens’s reliance on the original draft of the Second Amendment, in which the language about the necessity for a well-regulated militia had been followed by the statement that “no person religiously scrupulous of bearing arms, shall be compelled to render military service in person.” Stevens had argued that the inclusion of this exemption “confirms an intent to describe a duty as well as a right, and it unequivocally identifies the military character of both.” The majority disagreed. The exemption, it argued, “was not meant to exempt from military service those who objected to going to war but had no scruples about personal gunfights.” So in the majority’s view, “the most natural interpretation of Madison’s deleted text is that those opposed to carrying weapons for potential violent confrontation would not be ‘compelled to render military service,’ in which such carrying would be required.”

The majority had a similar take on the exemption language that had been proposed by Virginia and North Carolina, which would have provided that “any person religiously scrupulous of bearing arms ought to be exempted upon payment of an equivalent to employ another to bear arms in his stead.” While the court recognized that the phrase bear arms in his stead “refers, by reason of context, to compulsory bearing of arms for military duty,” it said that the phrase any person religiously scrupulous of bearing arms “assuredly did not refer to people whose God allowed them to bear arms for defense of themselves but not for defense of their country.”

In discussing the proposed conscientious-objector exemptions, the majority in Heller didn’t consider how the language at issue was likely to have been understood in the early 1780s and 1790s. Rather, it simply announced what it apparently thought was a self-evident truth (much as it had summarily applied the Muscarello dissent’s definition of carry a firearm to bear arms). But even accepting the majority’s characterization of the conscientious objectors’ religious beliefs, it does not follow that when framing-era Americans considered the issue of exempting such objectors from militia service, they focused on the objectors’ beliefs at the same level of close-up detail.

Rather, as I’ve suggested several times now, I think it’s likely that what they were concerned with was the aspect of the objectors’ beliefs that was most important to the objectors’ relationship with society at large: their objection to serving in the militia. But the majority didn’t examine the issue from that perspective; indeed, it probably never even thought of that as a possibility. And because it didn’t realize that there existed any perspective other than its own, it never offered any reason to think that its perspective was the appropriate one.

So at a minimum, it’s reasonable to reject the Heller majority’s argument on this point, and to interpret the references to religious objections to “bearing arms” as having been intended and understood as references to religious objections to serving in the militia. And going further, there is good reason to regard that interpretation as the most likely one.

Support for the latter conclusion can be found in the corpus data. I’m talking now about the seven concordance lines that I’ve categorized as “scrupulous of bearing arms (anaphoric)” and “scrupulous of bearing arms (implicitly anaphoric)” (Sec. 1e–1f, Lines 61–74.) An anaphor is a word or phrase whose interpretation is, as The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language puts it, “determined via that of [an] antecedent.” For example, pronouns typically function as anaphors, as in this sentence, in which “originalism” is the antecedent and “it” is the anaphor:

While originalismantecedent has many virtues—chiefly an encouragement of historical inquiry and an emphasis on the lawmakers’ meaning—itanaphor [= originalism] was hardly intended to sanction such untethered inquiries into contradictory signals[.] [Source, p. 272.]

Why does this matter? Because one would ordinarily expect the interpretation of the anaphor to match that of the antecedent, and therefore the immediate context in which the anaphor occurs can shed light on the meaning of the antecedent. Consider this example:

(31) You know that the United Brethren had allways some religious Scrupel of bearing arms, and as long as America has been under Great Britain, we have been exempt of that, and of swearing [Line 61.]

You know that the United Brethren had allways some religious Scrupel of bearing_armsantecedent, and as long as America has been under Great Britain, we have been exempt of thatanaphor [= bearing arms], and of swearing

The anaphor in “exempt of that” is understood to mean ‘exempt of bearing arms,’ and as I’ve explained, that constituted an exemption from the duty to perform military service. It follows that in the reference to a “religious Scrupel of bearing arms,” “bearing arms” was most likely to have been understood in the same way.

The same thing is true of (32)–(34), below,

(32) uses, without his own consent, or that of his legal representatives: Nor can any man who is conscientiously scrupulous of bearing arms, be justly compelled thereto, if he will pay such equivalent, nor are the people bound by any laws, but [Line 62.]

uses, without his own consent, or that of his legal representatives: Nor can any man who is conscientiously scrupulous of bearing_armsantecedent, be justly compelled theretoanaphor [= to bear arms], if he will pay such equivalent, nor are the people bound by any laws, but

(33) Mr. Sneitsan seconded this motion. He said that persons conscientiously scrupulous of bearing arms could not be compelled to do it [Line 64.]

Mr. Sneitsan seconded this motion. He said that persons conscientiously scrupulous of bearing_armsantecedent could not be compelled to do_itanaphor [= bear arms] [Line 64.]

(34) The freemen of this Commonwealth shall be armed and disciplined for its defence. Those, who conscientiously scruple to bear arms, shall not be compelled to do so; but shall pay an equivalent for personal service. [Line 67.]

The freemen of this Commonwealth shall be armed and disciplined for its defence. Those, who conscientiously scruple to bear_armsantecedent, shall not be compelled to do_soanaphor [= bear arms]; but shall pay an equivalent for personal service. [Line 67.]

Although anaphors usually take the form of words or phrases, they don’t always have to be embodied in an overt linguistic unit (such as do so). Instead, an anaphor can be associated with a position in the text at which semantic content is understood despite not being explicitly set out. For example, consider this sentence from Heller:

But their first use of the phrase (“any person religiously scrupulous of bearing arms”) assuredly did not refer to people whose God allowed them to bear arms for defense of themselves but not for defense of their country.

In this sentence, the boldfaced phrase conveys a meaning that goes beyond what the phrase explicitly says; it is understood as if it said allowed them to bear arms for defense of themselves but not to bear arms for defense of their country.

The fact that this represents an instance of anaphora becomes clear if you keep in mind that the implicit anaphoric content could be made explicit by using an expression such as to do so instead of the self-contained phrase to bear arms. The textual position where such an explicit anaphor would occur can be referred to as an anaphoric gap (see pp. 1082-1086), and the sentence can be notated to mark the gap’s existence and implicit content:

But their first use of the phrase (“any person religiously scrupulous of bearing arms”) assuredly did not refer to people whose God allowed them to bear_armsantecedent for defense of themselves but not __anaphor [= to bear arms] for defense of their country.

Returning now to the corpus data, the examples I categorized as “scrupulous of bearing arms (implicitly anaphoric)” are as follows (both without annotation and with):

(35) That any person religiously scrupulous of bearing arms ought to be exempted, upon payment of an equivalent to employ another to bear arms in his stead." [Line 68.]

That any person religiously scrupulous of bearing_armsantecedent ought to be exempted __anaphor [= from having to bear arms], upon payment of an equivalent to employ another to bear arms in his stead."

(36) judge or justice of the peace, that such persons have made oath or affirmation that they are conscientiously scrupulous against bearing arms, shall pay three dollars each as an annual commutation, to be collected as aforesaid. [Line 70.]

judge or justice of the peace, that such persons have made oath or affirmation that they are conscientiously scrupulous against bearing_armsantecedent, shall pay three dollars each as an annual commutation __anaphor [= in place of having to bear arms], to be collected as aforesaid.

(37) it difficult to modify the clause and make it better. It is well known that those who are religiously scrupulous of bearing arms, are equally scrupulous of getting substitutes. [Line 72.]

it difficult to modify the clause and make it better. It is well known that those who are religiously scrupulous of_bearing armsantecedent, are equally scrupulous of getting substitutes __anaphor [= to bear arms in their place] or paying an equivalent __anaphor [= of such service].

(38) what the latter had affirmed in his writings, that the conscience of a devout Christian would not allow him to bear arms, even at the command of his Sovereign. [Line 74.]

what the latter had affirmed in his writings, that the conscience of a devout Christian would not allow him to bear_armsantecedent, even at the command __anaphor [to bear arms] of his Sovereign.

My comments about these examples are the same as those about the examples that included explicit anaphors: the anaphors here convey the military sense of bear arms, and that provides evidence that the antecedents do as well.

THE REMAINING CATEGORIES of uses don’t require the kind of extended discussion as those we’ve considered so far. We’ll look first at the 157 concordance lines I’ve categorized under the heading “able to bear arms, capable of bearing arms, fit to bear arms, etc.” (Section 1h, Lines 122–278; these also include uses regarding inability to bear arms.). Here are some samples:

(39) The other states have upwards of 330,000 men capable of bearing arms: this will be a good army, or they can very easily raise a good army out of so great [Line 122.]

(40) hundred pieces of brass ordnance a month and manufactur’d one thousand muskets per diem. Meanwhile every male capable of bearing arms was drill’d, and as fast as possible, equip’d. [Line 124.]

(41) whether one or two Classes should be commanded to appear, but at least one half of the Men capable to bear arms should be calld into the Field. [Line 154.]

(42) raising, recruiting, and distributing them in winter quarters, that his subjects and militia were synonymous terms; every man who could bear arms was a soldier, and no one served out of his turn. [Line 191.]

(43) consisting of six millions of souls, (which number England is commonly said to contain,) the number of males capable of bearing arms (and who, according to natural right, are justly entitled also to a share in the legislature) would be estimated [Line 220.]

(44) a constant exercised militia shall be kept up, but by annual rotation: for which purpose, the fifth part of the men fit to bear arms, from seventeen to forty-five, shall be embodied for two months of the year, their manoeuvres as simple as can [Line 262.]

Given the military context in which the relevant language appears, it seems likely that in these examples, bear arms was used (and understood) in much the same sense as it was used in the various duty-to-bear-arms examples. In saying this, I don’t mean to suggest that these are instances of bear arms being used in a military context but conveying the sense endorsed by Heller. Rather, the relevance of the military context is that it makes it likely that bear arms was used (and understood) to convey the idiomatic military meaning that the majority in Heller rejected. The salient issue in these examples was the overall ability of people to perform military service, not merely their ability to carry weapons (for whatever purpose). And that would presumably have been reflected in the meaning that the authors meant to convey and that readers understood.

Note also the statement in (43) that “males capable of bearing arms” are “juſtly entitled alſo to a ſhare in the legiſlature,” which supports the conclusion that being able to bear arms had the kind of civic significance that would have been associated with serving in the militia and not with simply being physically able to carry weapons. [For related discussion, see the update below.]

Related to the various uses concerning the ability to bear arms is a group of concordance lines in which bear arms appears in expressions having to do with being old enough to bear arms (Section 1i, Lines 279–284):

(45) I prevailed upon the Baron to permit their return, both because several of the boys had been and might be enlisted for the war, and serve very well for music till they grow big enough to bear arms; and because we wanted them for the purpose of guarding stores here, in the room of better men who [Line 279 (text in red was accidentally deleted in the compilation of the corpus, and has been restored; source).]

(46) The wide extent of country might very possibly contain a million of warriors, as all who were of age to bear arms were of a temper to use them. [Line 280.]

(47) In the beginning of the war, the Roman people consisted of two hundred and fifty thousand citizens of an age to bear arms [Line 281.]

(48) of Phocis, and Baeotia, were inſtantly covered by a deluge of Barbarians who maſſacred the males of an age to bear arms, and drove away the beautiful females, with the ſpoil, and cattle, of the flaming villages. [Line 282.]

(49) CHAPTER IX. Of their Manner of making WAR, &c. THE Indians begin to bear arms at the age of fifteen, and lay them aside when they arrive at the age of sixty. [Line 283.]

(50) he might be enabled to defray thoſe of my education; and, as ſoon as I was at an age to bear arms, he led me himſelf into the paths of glory. [Line 284.]

(51) The women of the village, together with the youth who have not attained to the age of bearing arms, assemble, and forming themselves into two lines, through which the prisoners must pass, beat and bruise them with sticks [Line 285.]

Whereas the duty to serve in the militia applied only to those above a given age, I haven’t seen any indication that there were any minimum age requirements for being allowed to carry weapons. On the contrary, it appears that children learned to use firearms at a young age, and the fact that males were required to do militia service starting in their teenage years suggests that by that stage in life, they already knew how to use weapons. Unless I’m mistaken about the history, therefore, bear arms as used in (45)–(51) meant ‘perform military service’ or ‘act as a warrior.’

Update: Here are some further examples of able to bear arms and of [an] age to bear arms, which I found via Google Books, and which I think provide additional support for my reading of bear arms as used in such constructions:

able to bear arms

(51a) Soldiers by profession are, comparitively, but a modern invention; and y powerful nations have had no other defence, but a country militia. The Roman common wealth, in particular, for many ages had no standing army; but they had as many soldiers as men able to bear arms. They all learned the then art of war from their youth. They enlisted as volunteers whenever their country required their assistance, and then returned home to their farms and trades.… Virginia, upon an emergency, could easily spare an army of 10,000 men, to be draughted out of the militia, without leaving our families defenceless. Nay, I dare affirm, there is that number of men able to bear arms in this colony, who depend almost entirely upon the labour of their slaves, and do not so much as take the care of overseer upon themselves. [The Magazine of Magazines (1756). Source.]

(51b) It is said in the defence, that if 15,000 Frenchmen had landed, the consequence might have been fatal even to our capital; but it is remarked in the answer, that this once opulent and powerful island, containing two millions of men able to bear arms, must be reduced very low indeed, if 15,000 Frenchmen could force their way to our capital, and produce such scenes of ruin as cannot be conceived without horror. [The Magazine of Magazines (1756). Source.]

(51c) It is Voted and Resolved, that Mr. Job Watson be, and he is hereby, appointed a Post at Tower-Hill, to give intelligence to the Northern Counties, in case any squadron of Ships shall be seen off; that in case of an alarm, the Northern Counties be, and ther are hereby, ordered to march to the Town of Providence; that a Proclamation be immediately issued by his Honour the Deputy-Governour, commanding every man in the Colony, able to bear arms, to equip himself completely with Arms and Ammunition, according to law; and that the Town of Providence fix a beacon on the hill to the eastward of the said Town, to alarm the country, in case of an invasion.[(1775). Source.]

of [an] age to bear arms

(51d) He was no sooner of Age to bear Arms, but he followed his Father to the Army, and was present at the Siege of Breda, giving great proofs of his Courage, though but 13 years old. [The lives of all the princes of Orange (1682). Source.]

(51e) These are immediately conveyed to Gallipoli or Constantinople; where they are first circumcised, then instructed in the Mahometan faith, taught the Turkish language and the exercises of war, till such time as they become of age to bear arms; and out of these the order of Janizaries [an order of infantry in the Turkish armies] is formed. [Cyclopaedia, Or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (5th ed. 1741). Source.]

(51f) That martial nation resolved to make a new and more vigorous effort than ever. They published a law, commanding all who were of age to bear arms, to appear upon the first summons from the general of their nation, upon pain of death. [An Universal History, from the Earliest Account of Time (1747). Source.]

(51g) The city being now built, Romulus lifted all that were of age to bear arms into military companies, each company consisting of 2000 footmen, and 300 horse. [Plutarch’s Lives (translation published 1758). Source.]

(51h) In one Custom they differ from almost all other Nations; that they never suffer their Children to come openly into their Presence, until they are of Age to bear Arms: for the Appearance of a Son in publick with his Father, before he has reached the Age of Manhood, is accounted dishonourable. … Whilst Affairs were in this Posture at Ruspina, M. Cats, who commanded in Utica, was daily enlisting Freed-men, Africans, Slaves, and all that were of Age to bear Arms, and sending them without Intermission to Scipio's Camp. [The Commentaries of Caesar, translated into English (1779). Source.]

(51i) These same Tartars, who, perhaps, as has been observed above, have lost something of their first energy, are still, however, the best and bravest soldiers of the empire. Every Tartar of ordinary rank, is enrolled from his cradle. Every Tartar, of an age to bear arms, must be in a situation to go on the first signal, and ready to fight with order. [The Universal Magazine of Knowledge and Pleasure (1787). Source.]

(51j) had furnished the means of creating an army, by converting every man, who was of age to bear arms, into a soldier, not for the defence of his own country, but for the sake of carrying unprovoked war into surrounding countries [The speeches of the right honourable William Pitt in the House of Commons (1806) (speech delivered Feb. 3, 1800). Source.]

THIS LEAVES ONLY two categories of uses to be discussed

In one of these categories (Section 1j, Lines 285–417), bear arms is modified by a prepositional phrase (or an infinitival verb phrase) providing details about the action or activity that is being referred to—most often by identifying the enemy against whom arms were borne, but sometimes identifying the entity or cause that was being defended. For example:

bear arms against the United States

… against the British government

… against the king or his authority

… against the new republic

… in defense of our country

… in defense of American liberty

… in defense of this State

… to defend Independence

In expressions such as these, bear arms is unambiguously used in a military sense. Specifically what bear arms denotes in these uses is participating in hostilities, not simply serving in a militia or an army.

Even the justices in the Heller majority would have to agree with this conclusion, at least with respect to the uses following the pattern bear arms against X. After all, the majority began its discussion of the idiomatic military sense(s) of bear arms by saying that the phrase “unequivocally bore that idiomatic meaning only when followed by the preposition ‘against,’ which was in turn followed by the target of the hostilities.” (Emphasis by the court.)

But elsewhere in the opinion, the majority didn’t find comparable clarity in the North Carolina state constitution’s use of the phrase “bear arms, for the defense of the State.” The opinion said that that phrase “could plausibly be read to support only a right to bear arms in a militia,” but took the position that using bear arms to denote “only a right to bear arms in a militia” “is a peculiar way to make the point in a constitution that elsewhere repeatedly mentions the militia explicitly.” But as the corpus data shows, there was nothing unusual about using bear arms to mean ‘serve in the militia.’ And in any case, the court's argument by its own terms can’t be extended beyond the context of the North Carolina constitution, and therefore doesn’t apply to the uses in the corpus data of expressions such as bear arms in defense of independence [liberty, our country, etc.]. (The court's interpretation of the North Carolina provision also relied on a decision of the North Carolina Supreme Court in 1843. Given that that decision postdated the Second Amendment by more than 50 years, it is at best weak evidence of how the amendment was understood at the time it was ratified.)

The final category that I’ll discuss here consists of a hodgepodge of 83 uses that I’ve assembled under the self-explanatory heading “miscellaneous military.” (Section 1k, Lines 418–500.) Rather than discuss individual uses or groups of uses, I’m going to offer some examples and encourage you to check out the rest for yourself.

(52) his whole army had capitulated to General Gates, on condition of being permitted to return to Great Britain, and not bearing arms again in North America during the present contest. [Line 434.]

(53) He was a great Whig, and altho he did not serve his Country by bearing arms, yet by his Endeavours, he found out many Traiters as “Gallovay” & some others [Line 437.]

(54) Congress to recommend the restoration of confiscated estates to British subjects, who have not borne arms [Line 441.]

(55) until such-time as the regiment, troop, or company, to which the of*fender thall belong, thall be dilcharged from bearing arms on the occasion for which they shall be assembled [Line 444.]

(56) that in the mean time the prisoners delivered up by the enemy abstain from bearing arms or otherwise acting against them [Line 452.]

(57) I have sufficiently proved my courage and fortitude, both in the field, where I have borne arms with you, and in the senate [Line 460.]

(58) gave orders, on Auguſt. 30, 1780, “That every militia man, who had borne arms with us, and afterwards joined the enemy, ſhall be immediately hanged [Line 463.]

(59) All civil officers and citizens, who had borne arms during the siege, were to be prisoners on parole [Line 468.]

(60) he, with a party of young men who, as volunteers, had associated on the side of Government, bore arms, and was engaged in the skirmish at Falkirk [Line 471.]

(61) To this I replied, that many of us had borne Arms in Times paſt, and been in many Battles [Line 480.]

(62) They considered the vanquished party as composed of traitors who had borne arms, or otherwise had acted with hostility against the commonwealth [Line 488.]

(63) 1. THAT he ſhould attack the town in twenty-four hours. 2. THAT with reſpect to the Roman catholics who had borne arms, whether they belonged to the army or not, he ſhould act by the law of retaliation, and put them [Line 493.]

(64) to make war and peace, how shall all of the nation, who may be called to bear arms, be certain that there is cause sufficient to legitimate a war? [Line 500.]

Update: Bearing arms and the right to vote

In my discussion of uses such as able to bear arms and capable of bearing arms, one of the corpus examples (which is repeated below) referred to “males capable of bearing arms” as being, “according to natural right, … justly entitled also to a share in the legislature”:

(43) raising, recruiting, and distributing them in winter quarters, that his subjects and militia were synonymous terms; every man who could bear arms was a soldier, and no one served out of his turn. [Line 191.]

I said that this example “supports the conclusion that being able to bear arms had the kind of civic significance that would have been associated with serving in the militia and not with simply being physically able to carry weapons.” After this post went live, I found additional evidence supporting that conclusion—in fact, evidence that supports the conclusion more strongly than (43) does by itself.

The first piece of evidence is from the corpus data, where it is categorized under the heading “miscellaneous military,” category, but I hadn’t previously focused on it. It is similar to (43), in that it refers to “each freeman that bears arms as” being entitled to “his natural right of suffrage in the state, his due share of legislative influence”:

(65) being limited, and equal to all men in duration, it would be no great hardship, especially if each freeman that bears arms was allowed his natural right of suffrage in the state, his due share of legislative influence, to controul the [Line 474.]

The similarity between (43) and (65) isn’t coincidental, because it turns out that both excerpts are from the same source. In fact, they appear on the same page, only seven words apart.

The source is Tracts, Concerning the Ancient and Only True Legal Means of National Defence, by a Free Militia (link), by Granville Sharp (first published in 1781). Sharp was an Englishman and he was writing about the English militia, but he and his work were known to Americans such as George Washington, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin, each of whom owned copies of various books by Sharp, including his Free Militia tracts (GW, JA, BF).

Examples (43) and (65) are from the tract titled, “A General Militia, Acting by a Well-Regulated Rotation, Is the Only Safe Means of Defending a Free People.” As the title suggests, this tract proposed the formation of a national militia organized on the principle that service “be divided into equal proportions of attendance, by rotation,” so that each person who was able to bear arms would serve a total of one month over the course of a year. Among the advantages that Sharp saw in such a plan was that the periods of service wouldn’t be long enough for those who were serving at any given time to develop interests separate from those of the their fellow citizens, as was thought to occur among the soldiers in a standing army. (These themes will echo in some of the materials that will be featured in my next post.)

Here is the passage from which (43) and (65) are taken:

The general body of individuals, in such a case, indeed, submit themselves to serve, by rotation, in the humble station of private soldiers; but the time of service being limited, and equal to all men in duration, it would be no great hardship, especially if each freeman that bears arms was allowed his natural right of suffrage in the state, his due share of legislative influence, to controuI the commanders, and regulate the service.

In a nation consisting of six millions of souls, (which number England is commonly said to contain,) the number of males capable of bearing arms (and who, according to natural right, are justly entitled also to a share in the legislature) would be estimated at a fourth part of that number,…, viz. 1,500,000 men; from which number a Roster of actual service from home, only for one month each man in the space of a whole year, would supply a constant army in the field of 125,000 men, if so many were necessary. [Italicization omitted.]

It seems to me beyond doubt that in this passage, Sharp was using bear arms to mean ‘serve in the militia’—both because of the context and because it would be bizarre to grant people the right to vote simply because they have physically carried weapons for the purpose of being prepared for confrontations.

As it happens, Sharp’s book was cited by the Supreme Court in Heller, but not the particular tract I’ve been discussing. The court cited the tract titled “The Ancient Common-Law Right of Associating with the Vicinage, in every County, District, or Town, to Support the Civil Magistrate in Maintaining the Peace,” and it cited it in support of the proposition that the rights of Englishmen “of having and using arms for self-preservation and defense” were not tied to service in the militia or military. Nowhere in that tract did Sharp use the phrase bear arms (or any variant of it). The portions cited in Heller therefore can’t shed any on what that phrase was understood to mean.

The other examples I’ve found of bear arms being used in a context relating to voting rights are from American sources, and in each of them, use of bear arms was almost certainly intended to convey the meaning ‘serve in the militia.’

Like (65), the first of these examples is from the corpus data—again from the “miscellaneous military” category—and as with (65) I hadn’t previously recognized its significance:

(66) This Province has been thrown into much Confusion lately on Account of Elections; in several Counties It has been determined contrary to an express Order of Convention, that every Man who bears Arms is intitled to Vote. This is in my Opinion is a dangerous Procedure, and tends to introduce Anarchy & Confusion [Line 432, with extended context.]

(This passage is from a letter to George Washington written in August 1776 by his stepson, John Parke Custis. An account of the circumstances to which Custis refers can be found in The Price of Nationhood: The American Revolution in Charles County, by Jean B. Lee, at pages 130-131.)

The last two examples are from records relating to the ratification of the Massachusetts constitution of 1780.

In its deliberations on the proposed constitution, the Town of Adams, in Berkshire County, voted “that Every individyal Bairing Arms or doing Duty ought of Right to have a Voice in Electing his Own officer[.]”

Similarly, the Town of Westhampton, in Hampshire County, voted with regard to the article regarding the “qullifycations of Soldiers to vote for their officers” that “all persons [who?] are obliged to bear arms have a Right to vote for their Commissioned of[ficers yeas?]” (bracketed insertions are by the editors of the volume in which the records are published). The reason for that vote is set out:

[S]ince the persons from sixteen years to twenty one years of age are the persons that are called upon to go into the field and are obliged to trane under those officers and perhaps have born as great or greater share of the Burden of the presen[?] contest as person of any age whatever we therefore Concider them as not only haveing a just right to choose, but as haveing Sufficien knowledge of the qualifications of an officer.

[Spelling as in the original.]

I discovered these two excerpts via No Guarantee of a Gun: How and Why the Second Amendment Means Exactly What It Says, by John Massaro. The records from which the excerpts were taken are published in The Popular Sources of Political Authority: Documents on the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 (Oscar Handlin & Mary Handlin, eds.). Screencapped copies of the relevant pages are available here, in the folder named <4 'bear arms,' etc>. The copies are hard to read, but they’re the best I could do.

—♦—

I MENTIONED at the beginning of this post that I’m not the first person to conclude that bear arms was predominantly used in its military sense(s). I want to acknowledge those who have preceded me, and to talk in a little more detail about the work of one of those people, because he has generously shared some of his data with me.

In the 14 months since the BYU Law Corpora were made publically available, studies have been done by Dennis Baron (the principal author of the linguists’ amicus brief in Heller) and by Josh Blackman and James Phillips. The Blackman & Phillips study is especially noteworthy because of who the authors are. Both of them are gun-rights advocates, and Phillips was, as I understand it, the person who originally came up with the idea of having the BYU Law School assemble a corpus designed for doing research about the original meaning of the Constitution. Both Baron and Blackman & Phillips made presentations at the Law and Corpus Linguistics Conference this year at BYU, and you can watch a video of their panel (which also includes a very interesting presentation by Viola Miglio) here.

Before the BYU Law Corpora existed, the first people to report that the use of bear arms had been overwhelmingly military were law professors Michael Dorf and David Yassky, in separate articles published in 2000. Their conclusions were based on searches of Congressional records in Library of Congress databases. But the court in Heller was untroubled by the predominance of military uses in such records, stating, “Those sources would have little occasion to use it except in discussions about the standing army and the militia.”

The other relevant publications that I’m aware of are by the historians Saul Cornell and Nathan Kozuskanich, both of whom relied on the Evans collection and the Early American Newspapers databases (covering the period 1690–1800). Cornell’s conclusions were cited and discussed in the linguists’ amicus brief in Heller, but from what I can tell, the data itself was not submitted to the court. A paper by Kozuskanich reporting his conclusions was cited in the District of Columbia’s reply brief, but again, it doesn’t appear that the court was provided with the data. In its decision, the court said nothing about Kozuskanich’s study, and although it acknowledged the linguists’ discussion of Cornell’s data, the fact that the court hadn’t been shown the data enabled it to minimize the data’s importance. The court expressed skepticism about the accuracy of the linguists’ conclusion: “Justice Stevens points to a study by amici supposedly showing that the phrase ‘bear arms’ was most frequently used in the military context.” (Boldfacing added.) It also said, “The study’s collection appears to include (who knows how many times) the idiomatic phrase ‘bear arms against,’ which is irrelevant.” As I discussed in the first of my posts on bear arms, the court’s conclusion that uses of bear arms against was based on reasoning that, if applied evenhandedly, would have required the court to reach the same conclusion about evidence that was crucial to the court’s interpretation.

In 2009, after Heller was decided, Kozuskanich published another paper examining late-18th century American usage of bear arms. By this time, he had collected more uses than he’d had for the first paper (and more than Cornell had). Here is the second paper’s description of the searches Kozuskanich performed and the results he obtained:

A search of the exact phrase "bear arms" in all the text of documents dated 1750 to 1800 in the Evans collection returns 563 individual hits. If we discard reprints of Rights and all references to the text of the Second Amendment Congressional debate, irrelevant foreign news, reprints of the Declaration of Independence, and all repeated or similar articles, 210 documents remain. All but eight of these articles use the phrase "bear arms" within an explicitly collective or military context to indicate military action. Likewise, the same search of the Early American Newspapers yields 143 relevant hits, of which only three do not use the connote a military meaning.

Kozuskanich was kind enough to share with me tables in which he recorded the relevant uses, together with citations to each source. With his permission I have posted them here, along with my spreadsheets presenting the data from COFEA and COEME.

From what I’ve been able to determine, there is no overlap between Kozuskanich’s data and mine. Neither COFEA nor COEME draws on the American Newspapers database, and although the Evans collection is one of the sources for the two corpora, only a third of the Evans materials were made available to BYU. On top of that, my impression is that when Kozuskanich did his analysis, only a subset of the Evans documents had been put online.

Although for the most part Kozuskanich’s tables don’t present as much context as appears in the concordance lines from COFEA and COEME, there’s enough there to suggest to me that his categorizations are accurate. So if we accept his results and consider them together with mine, the pool of data that is inconsistent with Heller (not including lines that are ambiguous) is increased by about two-thirds, from 505 to 847.

[Comments have been closed.]

Cross posted on LAWnLinguistics.

Hector said,

July 10, 2019 @ 6:51 pm

These posts have been awesome. I look forward to seeing them relied upon in a SCOTUS dissent!

ardj said,

July 11, 2019 @ 6:06 am

Remarkable and interesting work, thank you very much.

Two questions from a complete ignoramus in either words or US law context – feel free not to reply.

Were there a lot of people "who objected to going to war but had no scruples about personal gunfights" or in other words, were such likely to be considered kindly in writing the Constitution; and supplementararily, did the Constitution permit personal gunfights ?

ambisinistral said,

July 11, 2019 @ 7:34 am

I have not closely followed this series of posts, but they did come to mind when I read The Volokh Conspiracy's post Corpus Linguistics in Court?

You might find it interesting.

Joe said,

July 11, 2019 @ 9:49 am

@ardj: "Were there a lot of people 'who objected to going to war but had no scruples about personal gunfights'…?"

That's the majority's reductio ad absurdum argument to Stevens's assertion that a "person religiously scrupulous of bearing arms" signaled opposition to military action rather than guns in general. Quakers, for example, were explicitly against military action during the American Revolution (with some exceptions such as Betsy Ross and the Free Quakers) which included paying war taxes, etc. Ironically, all of the colonies had gun laws requiring citizens to register their firearms for military service – except for Quaker-dominated Pennsylvania. These kinds of laws are considered by modern gun advocates as an infringement of the 2nd Amendment.

Jonathan Lemaire said,

July 11, 2019 @ 11:14 am

In this day and age, with the millions of guns currently in circulation, it really doesn't matter what was said in any amendment…Good luck getting rid of those!

FDChief said,

July 11, 2019 @ 11:29 am

The clear reading of the text – regardless of the meaning of the term "bear arms" in the 18th Century – refers to military service. When combined with what we know of the Framers' prejudice against standing armies the reference is fairly obvious; the "People" in arms were intended to be the Defense Department of the day. When you DO combine that with the contemporary understanding of the term "keep and bear arms" the meaning is crystal clear; the Framers meant this as a means of national defense. The interpretation of the 2A as an individual right to walk around armed is nonsensical.

But that, then, points us back to Heller which was, as so much of "conservative" jurisprudence is, not an actual attempt to align lower court decisions and legislative actions with the Constitution, but a means or ensuring an outcome that "conservatives" like; owning as many AR-15 knockoffs as you can afford because gunz are fun.

This is a truly impressive piece of scholarship. It will affect the Roberts Court's firearms opinions – and any other "conservative" judicial review – about as much as an exgesis on the pronouncements regarding transubstantiation by the Council of Trent

Benjamin E. Orsatti said,

July 11, 2019 @ 11:38 am

Neal,

Maybe it's just sour grapes, owing to the fact that I, myself, have neither the time, nor the intellect, required to undertake such a heroically comprehensive endeavor as you have done, but the following thought has occurred to me: Apart from the project's inestimable value to the field of historical linguistics and legal theory, is it not, perhaps, somewhat misplaced for _advocates_ to rely too heavily on corpus analysis when making persuasive arguments to the highest court in the land?

That is to say, isn't there a risk of vesting too much power in the authority of strict constitutional originalism, as a legal theory? I'm not suggesting that the advocates in any given case have "put all their eggs in one basket", as it were — lawyers make "arguments in the alternative" as a matter of course, and I'm sure that the appeal to originalism is just one of many arguments made before the SCOTUS. However, if a pending case is ultimately decided _on the basis of_ this strict originalist argument, doesn't that help give strict originalism more "prestige" as a controlling principle of law?

In this case, it certainly seems like the best way to convince a conservative-majority court would be to appeal to originalism, but doesn't the difference between "judicial restraint" and "judicial activism" depend on whose ox has been gored? Maybe the same people who are using the "weapon" of originalism against proponents of stronger gun rights might not be so eager to "bear" that particular "arm" the next time an issue arises that _doesn't_ benefit from an originalist interpretation bolstered by corpus linguistics.

All that to say, especially for the folks playing along at home who might not be lawyers, I can't resist pointing out that strict textual constitutional originalism isn't the only game in town. Jurists also have recourse to:

(1) The intentions of those who drafted, voted to propose, or voted to ratify the provision in question (e.g., "WWJMD?" (What would James Madison Do?));

(2) Prior judicial and administrative precedents (Stare decisis, i.e. "What did the court decide in this factually-similar case"?);

(3) The social, political, and economic consequences of alternative interpretations (e.g. "We used to permit slavery, now we don't; we used to forbid alcohol, now we don't"; and

(4) Natural law (I.e. the "unalienable rights" part of: "We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights").

Harley Hays said,

July 11, 2019 @ 2:10 pm

It is possible to justify anything if the writer argues what might be. Obfuscation in this case is useful in changing the obvious meaning meaning of the second amendment. In other words the author relies on the old saw, "if you can't dazzle the with brilliance, baffle them with bullshit".

DWalker07 said,

July 11, 2019 @ 2:31 pm

@Jonathan Lemaire:

"In this day and age, with the millions of guns currently in circulation, it really doesn't matter what was said in any amendment…Good luck getting rid of those!"

Who is trying to get rid of anything? This is a scholarly discussion of the meaning of "bear arms" as used in the Second Amendment.

DWalker07 said,

July 11, 2019 @ 2:35 pm

For those who may be interested in this kind of discussion and reasoning, I recommend Lawrence Lessig's fascinating book "Fidelity & Constraint: How the Supreme Court Has Read the American Constitution". The book has one unfavorable review at Amazon, but I find it quite interesting (I'm not finished yet).

Kevin Butterfield said,

July 11, 2019 @ 2:59 pm

Give it a rest, liberals. What a colossal waste of time.

ardj said,

July 12, 2019 @ 4:25 am

@Joe: thanks, but I did actually read the post. I can understand that some might have guns for hunting for instance. but be reluctant to use them against their fellow men. But I am not clear if the Constitution supports the majority argument by permitting civilian gun-fights

Rodger C said,

July 12, 2019 @ 8:17 am

I am not clear if the Constitution supports the majority argument by permitting civilian gun-fights

Burr and Hamilton certainly thought so, although Burr would be an odd choice as an authority on the Constitution.

But you're quite right, there's still a whole culture out here where people hunt, and that's fundamentally what firearms are for, and shooting people doesn't occur to them any more often than it does to anyone else, and they don't see what the fuss is about.

Benjamin E. Orsatti said,

July 12, 2019 @ 11:15 am

@ Roger C.

Seem like a reasonable application of "(3) The social, political, and economic consequences of alternative interpretations (e.g. 'We used to permit slavery, now we don't; we used to forbid alcohol, now we don't'" might be the following.

P: Most crimes involving firearms are committed using either handguns or automatic or semi-automatic weapons;

P: Most hunters do not use handguns or automatic or semi-automatic weapons;

P: At the time of drafting, the Framers of the Constitution would not have recognized (and therefore could not have intended) anything other than a flintlock, front-loading musket;

————————————————–

C: Laws limiting the possession of handguns and automatic or semi-automatic weapons are constitutional.

C: Laws limiting the possession of hunting rifles are not constitutional.

Peter Gerdes said,

July 12, 2019 @ 11:44 am

The fact that the phrase "bear arms" had military connotations is clear and unambiguous. But that's a very different claim from what seems to be implicitly pushed here: namely that the use of that phrase indicates a right which is limited to military contexts is fallacious. In particular, the framers assumed that military usage meant that individuals owned and kept in working order military appropriate weapons in their houses

I think there is a very compelling argument that your analysis here actually shows the majority in Heller narrowed the interpretation of the 2nd amendment far too much. You are totally correct that built into the words is the assumption of military use. As such the most compelling analysis of the 2nd amendment would bar congress from passing any law restricting individuals from keeping weapons appropriate to modern military service (i.e. assault rifles in automatic mode).

In particular, for that protection to mean anything it can't be congress (and, via incorporation under the 14th, the states) who has the power to implicitly ban the citizen militia by deciding it only needs the national guard or whatever. At worst having a bunch of friends you march around in the woods with and shoot things would be enough to secure the right to keep working weapons of the type issue to the average infantry soldier in one's house.

—

One could mount a reasonable argument that handgun regulation isn't affected by the 2nd amendment as these aren't the kind of weapons regularly used by infantry and I personally think the most effective gun legislation we could pass is to ban handguns. But, bizarrely, despite handguns being responsible for 95% of gun homicides gun control advocates always seem to want to ban 'unnecessary' guns that people own for fun and to feel powerful even though those aren't the main problem and, indeed, are least well suited to the commission of violent crime in the modern age.

Peter Gerdes said,

July 12, 2019 @ 11:56 am

To make the point more briefly the connection between "bear arms" and military usage doesn't have the consequences that gun control advocates seem to assume.