First grade science card: Pinyin degraded

« previous post | next post »

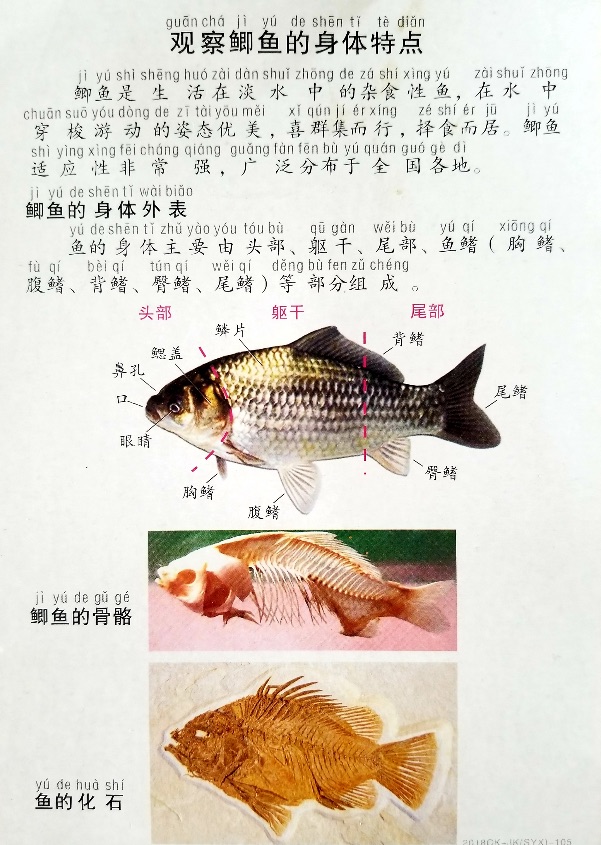

Science card given out to first grade students in Shenzhen, China:

Guānchá jìyú de shēntǐ tèdiǎn

观察鲫鱼的身体特点

("Observation of the physical characteristics of the crucian carp")

The vocabulary and mode of expression are obviously far beyond the first grade level. Some of the characters on the card won't be learned until high school, if then, yet the makers of this card have gone to the trouble of providing Pinyin phonetic annotations for all of the terms.

If the people who added the Pinyin really wanted to be helpful, they should have joined the syllables of words together, e.g., the last term on the card: huàshí 化石 ("fossil"). The way it is written now, with the syllables separated, might lead a student to think of it as "transformed stone".

This leads to a very sad chapter in the recent history of Chinese language pedagogy. When I started going to China in the early 1980s, the syllables of Pinyin terms were joined together and there were spaces between words. This was called "fēncí liánxiě 分词连写". It was a matter of pride among progressive language educators to provide schoolchildren with this extra information about the vocabulary they were learning.

Not only that, in many parts of the country there was a remarkable program called "Zhùyīn shìzì tíqián dúxiě 注音识字提前读写" ("Phonetically Annotated Character Recognition Speeds Up Reading and Writing"), or "Z.T." for short, which actively encouraged children to use Pinyin Romanization for characters they were unable to write. See "How to learn to read Chinese" (5/25/08).

In those days, schoolchildren began to learn to read and write with Pinyin-only texts, and they were properly segmented into words. That was when language reform was taken seriously in the PRC and the "Wénzì gǎigé wěiyuánhuì 文字改革委员会" ("Script Reform Committee") was directly under the powerful Guówùyuàn 国务院 (State Council).

This was also the time when the official rules for Hànyǔ pīnyīn zhèngcífǎ 汉语拼音正词法 ("Hanyu Pinyin Orthography") were formulated (drafted in 1982 and promulgated in October of 1984). Here's the latest version (2012) of the orthographic rules. An English translation (by John Rohsenow) of the previous edition (1996) of the orthographic rules is printed at the back of all ABC Chinese-English dictionaries from the University of Hawai'i Press.

Later, the power of the Script Reform Committee was greatly weakened when its name was changed to the State Language Commission (Guójiā yǔyán wénzì gōngzuò wěiyuánhuì 国家语言文字工作委员会) and it was placed under the Ministry of Education (Jiàoyù bù 教育部). It is no accident that, after that happened, educational materials no longer adhered to the orthographical rules, but phonetically annotated the characters one syllable at a time. This vexed Wang Jun, one of the leading language planners and reformers of China, so greatly that he died shortly thereafter (he himself told me not long before his death that he was "so angry he could die" [qì sǐle 气死了]).

After that, everything went downward and backward, with increasing emphasis on Sinographs (Hànzì 汉字) right from the beginning of primary education. It is also significant that currently reigning language authorities are dead set against joining of syllables and separation of words in the limited circumstances when Pinyin is unavoidable. Why are they so afraid of teaching and using word-based Pinyin? You tell me.

Readings

- "Character Amnesia" (7/22/10)

- "Character amnesia revisited" (12/13/12)

- "Spelling bees and character amnesia" (8/7/13)

- "Character amnesia and the emergence of digraphia" (9/25/13)

- "Diglossia and digraphia in Guoyu-Putonghua and in Hindi-Urdu" (1/1/12)

- "Sayable but not writable" (9/12/13)

- "Pinyin in 1961 propaganda poster art" (12/29/17)

- "Words in Mandarin: twin kle twin kle lit tle star" (8/14/12)

- "The uses of Hanyu pinyin" (5/22/16)

[h.t. Alex Wang]

Bathrobe said,

April 11, 2019 @ 7:07 pm

I hope you realise the difficulty of being an EDUCATOR and EDUCATED at the same time. Some just don't make the grade.

I had noticed the emphasis on Chinese characters in Chinese education, as reflected in school textbooks. The Chinese are often said to think in terms of characters rather than words, as though that were their natural state, but early-age education, where basic concepts are inculcated into the child and later taken for granted, must surely play a major role in moulding people's thinking.

The concept that each character is a single word is closer to the truth for Literary Chinese than it is for the modern language. Could the emphasis on characters rather than words conceivably have an impact on people's written style, by encouraging them to use a more concise literary style (based on characters and chengyu) rather than a more diffuse vernacular style based on words?

Antonio L Banderas said,

April 11, 2019 @ 8:19 pm

Would a Chinese company or educational institution take on an employee with a good qualification only in the oral part of the official examination HSK, that is the HSKK?

If not, the day they do word-based Pinyin will gain the relevance it deserves.

Alex said,

April 11, 2019 @ 8:48 pm

@ Antonio L Banderas

I think most Chinese companies are ecstatic if their expats can speak Chinese at all.

So to answer your question yes they would and they have both in educational and non educational industries.

Having non split pinyin words help many expats learn the oral part of putonghua quickly.

I know several people who teach expats Chinese and they often post wechat moments of their students notes.

You would be amazed by how many adult students naturally realize they don't need to learn the handwriting component of Chinese.

Alex said,

April 11, 2019 @ 8:53 pm

As a non linguist, I was wondering what are the other countries that use another script to teach natives the base script of their own country. For example in China they use pinyin to teach the natives how to read Chinese characters.

Daniel said,

April 12, 2019 @ 9:38 am

Alex, this is only necessary for base scripts that are not phonetically regular. Several scripts have been proposed for English for initial teaching of students, as it has quite a few irregularities, but they haven't gained much traction. See http://omniglot.com/conscripts/unifon.htm and other alternatives in links at the bottom of the page.

The use of pinyin to teach might be compared to the use of dots in Hebrew or explicit vowel marks in Arabic (or other Semitic languages) that are used in teaching children (or in sacred texts, where accuracy is of paramount importance) but not for adult communication. However, these additions are not considered to be a script from another country. (Although, the vowel marks for western Syriac ultimately derive from Greek.)

Guan Yang said,

April 13, 2019 @ 10:23 am

Daniel and Alex, I believe (from a pst Language Log post) that IPA is fairly widely used by Chinese learners of English.

Phil H said,

April 14, 2019 @ 10:28 am

I can confirm that the backsliding continues. This week my younger boy, in second grade in a state primary school in southern China, was asked to learn by heart the first five stanzas of the Three Character Classic without any support in terms of the meaning or the allusions. The refusal to recognise that Classical Chinese is a distinct language is one of the most damaging failures in the Chinese curriculum, but the teachers apparently imagine that children should learn to mindlessly recite sounds they can't even understand. A few years ago, when my older child was this age, there did not seem to be so much of this nonsense.

jin defang said,

April 14, 2019 @ 11:13 am

so just as children were taught in pre-modern schools: learn to recite the Confucian classics without knowing what they were reciting. "Education with Chinese characteristics."

Alex said,

April 14, 2019 @ 4:51 pm

@Guan Yang

Thanks for the reply. Though my question asked was people using another script to learn their own native language.

For example people born in the US, Australia, UK don't use IPA to learn English, their own language.

Mainly I was wondering about Japanese since I know nothing about it.

Alex said,

April 14, 2019 @ 5:07 pm

@ Phil H

If it were only memorizing for oral delivery, which started with Tang poetry in first grade. They progress to copying pages word for word by hand to show that they practiced handwriting. Often my older son's homework is to turn in word for word copying of 2 pages of text. Of course for assignments like this, the dog (cat in our home) always seems to eat his homework, which is ok by me.

Alex said,

April 14, 2019 @ 5:10 pm

@daniel

Thanks. Im glad i wasnt subjected to http://omniglot.com/conscripts/unifon.htm

growing up!

Alex said,

April 14, 2019 @ 9:55 pm

@phil

I just hope the school system your son encounters in the third grade doesn't also have the brilliant idea of making all kids write with the disposable ink cartridge fountain pen style pens. You cant even imagine the mess for that year.

Ian said,

April 15, 2019 @ 4:23 am

What are the phonetic processes in Chinese that distinguish one two syllable word from two standalone words?

Using the example above, are there clear/systematic differences between spoken huàshí and huà shí?

Jacob Gerow said,

April 25, 2019 @ 10:41 am

Are there any high level texts, either novels or other literature, which have the Characters and pinyin one on top of the other? Bonus points if the syllables are connected like what is being discussed in this article?

I want to enjoy Chinese literature but I suffer from Character amnesia. 4 years of Chinese and then a few years of no reading and its all gone!

Victor Mair said,

April 25, 2019 @ 2:20 pm

@Jacob Gerow

I've pleaded with Chinese language and education authorities on precisely this point, but so far my words have fallen on deaf ears. As a matter of fact, two and more decades ago, there were such materials available in schools and bookstores, but under the new retrograde regime, things have gone downward and backward in the last few decades.

As I have mentioned in numerous posts (a few are cited below), I learned most of my written Chinese (reading and writing) — relatively painlessly — with the aid of Zhùyīn fúhào 注音符號 (bopomo ㄅㄆㄇㄈ (Mandarin Phonetic Symbols).

"How to learn to read Chinese" (5/25/08)

"Bopomofo vs. Pinyin" (4/28/15)

"The end of the line for Mandarin Phonetic Symbols?" (3/12/18)

"How to teach Literary Sinitic / Classical Chinese" (9/6/18)

"Writing Sinitic languages with phonetic scripts" (5/20/16)

"Another use for Mandarin Phonetic Symbols" (3/29/18)

If Taiwan can do this with bopomofo, there's no reason why China cannot do it with Hanyu Pinyin. It would make life so much easier and more efficient for Chinese schoolchildren, and it would be a great boon for spreading Mandarin as a true world language. I think that it is long past the time for enlightened educators and language reformers to promot