Historical culturomics of pronoun frequencies

« previous post | next post »

Jean M. Twenge, W. Keith Campbell and Brittany Gentile, "Male and Female Pronoun Use in U.S. Books Reflects Women’s Status, 1900–2008", Sex Roles published online 8/7/2012. The abstract:

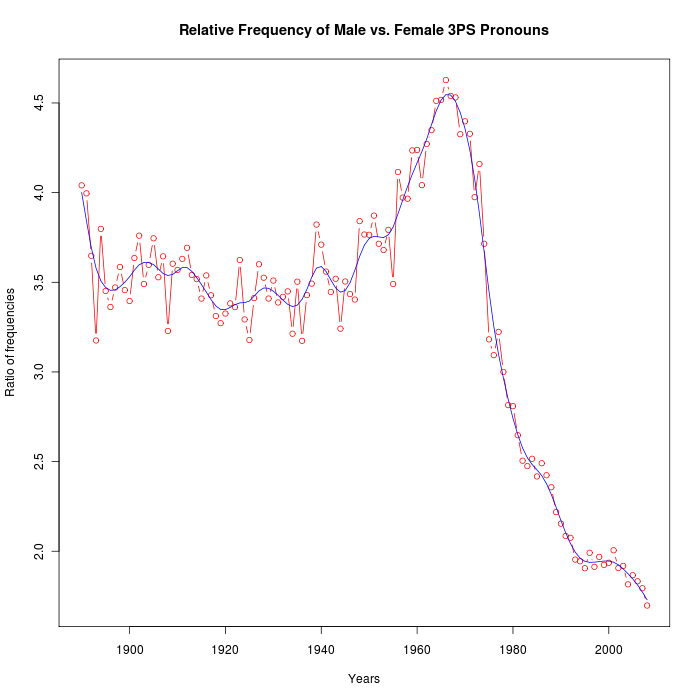

The status of women in the United States varied considerably during the 20th century, with increases 1900–1945, decreases 1946–1967, and considerable increases after 1968. We examined whether changes in written language, especially the ratio of male to female pronouns, reflected these trends in status in the full text of nearly 1.2 million U.S. books 1900–2008 from the Google Books database. Male pronouns included he, him, his, himself and female pronouns included she, her, hers, and herself. Between 1900 and 1945, 3.5 male pronouns appeared for every female pronoun, increasing to 4.5 male pronouns during the postwar era of the 1950s and early 1960s. After 1968, the ratio dropped precipitously, reaching 2 male pronouns per female pronoun by the 2000s. From 1968 to 2008, the use of male pronouns decreased as female pronouns increased. The gender pronoun ratio was significantly correlated with indicators of U.S. women’s status such as educational attainment, labor force participation, and age at first marriage as well as women’s assertiveness, a personality trait linked to status. Books used relatively more female pronouns when women’s status was high and fewer when it was low. The results suggest that cultural products such as books mirror U.S. women’s status and changing trends in gender equality over the generations.

Here's their plot of the ratio between the frequencies of male (he, him, his, himself) and female (she, her, hers, and herself) third-person singular pronouns:

As is all too usual these days in scientific publications, alas, Twenge et al. don't give us the complete recipe for their work — for example, they don't tell us how they treated the case of letters. Modulo this uncertainty, here's my replication of the same ratio from the same source:

As I observed in an earlier post, apparent historical trends of this kind in word frequencies or in ratios of word frequencies can have several qualitatively different sorts of explanations:

- The mix of kinds of books published changes over time (e.g. more romance novels, fewer collections of sermons); different kinds of books use words differently; therefore the relative frequency of words changes.

- The mix of kinds of books selected for the Google Books ngram collections changes over time; so the relative frequency of words changes, for similar reasons as in (1).

- The distribution of concepts or conceptual frames changes over time, even in the same sorts of books.

- The choice of words to express a given concept (in published books) changes over time, even in the same sorts of books.

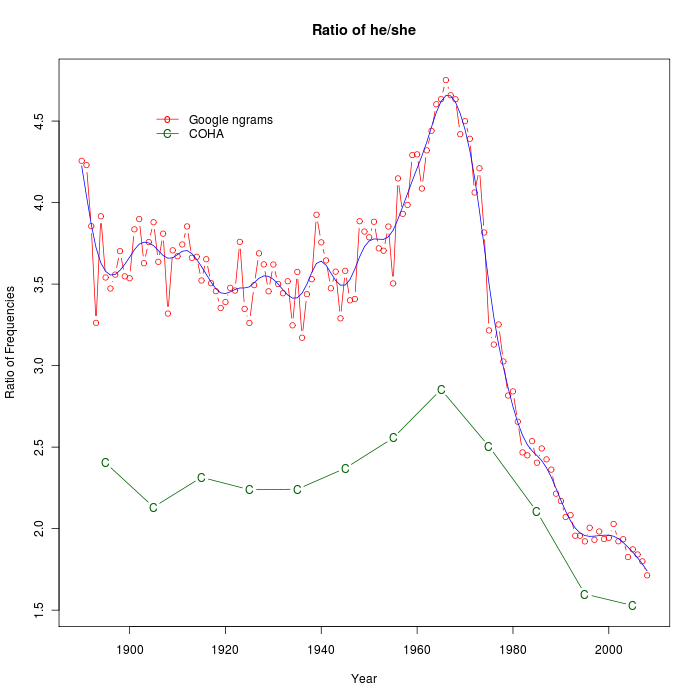

David Brown ("Gender Pronouns in the News", Grammar Lab 8/12/2012) tries to address part of this uncertainty by calculating a similar ratio (of gendered pronouns) using data from an independent source, namely the Corpus of Historical American English. David looked only at he and she, rather than the full set of masculine and feminine third-person singular pronouns, but this turns out not to make much difference. Here's a plot showing he/she for both the Google Books American English ngrams and COHA:

As David notes, these time-series are "similar, though slightly different". But at least they show a qualitatively similar pattern of rises and falls — the difference is probably due to a different mix of types of material. The qualitative similarity of the time-series of ratios should help to reassure us that the overall rise and fall is not due to some artefactual change in the sampling of book genres in the Google Books American English ngram collection.

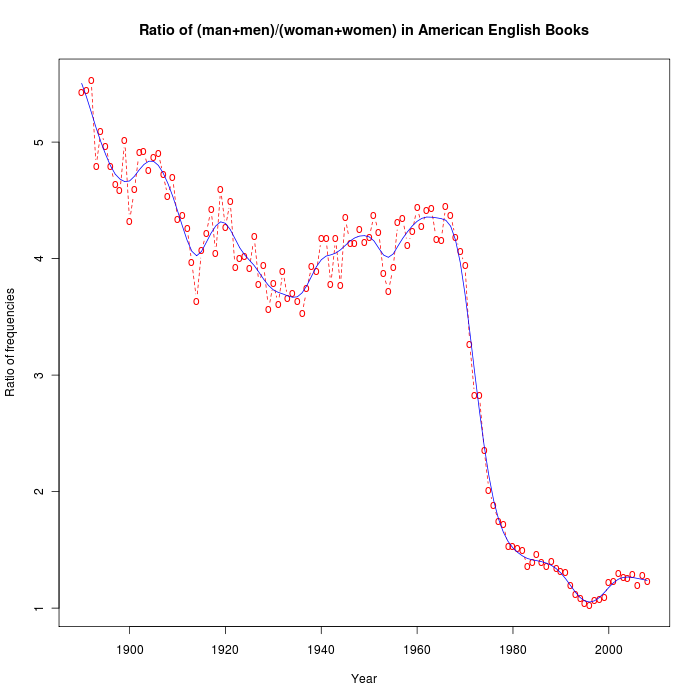

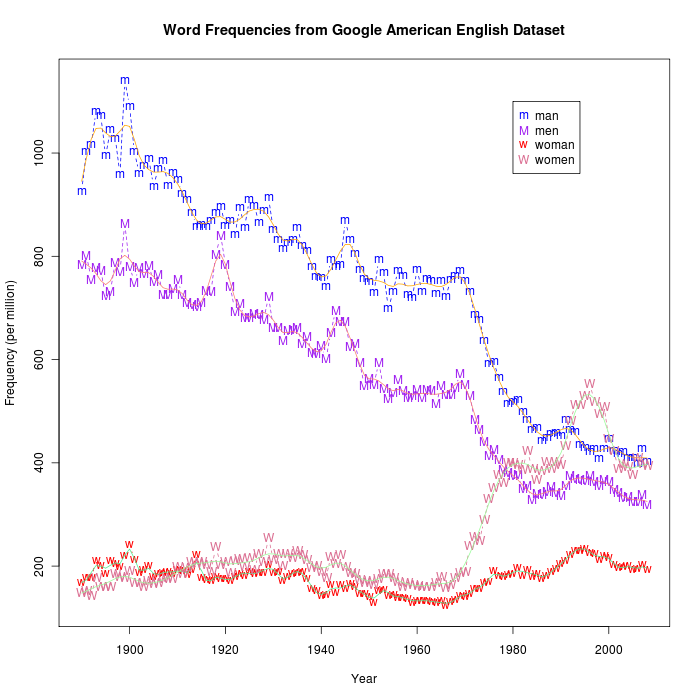

Another sort of replication would look at time-series of different words that relate to the same concepts — here's man+men versus woman+women, which shows an even bigger post-1960 fall, but a less clear pattern before that. This should help reassure us that the post-1960 fall probably does have something to do with changes in the frequency of references to the underlying concept:

As with the pronoun data, the change is more driven by a fall in male (or nominally sex-neutral?) references than by a rise in female ones:

And there appear to be blips in male references associated with the two world wars and with the Vietnam war, suggesting that one factor in the trend might be changes in the overall amount of writing about war.

Anyhow, I'm glad to see that Twenge et al. start their paper by showing a convincing graph. Another recent work by the same authors didn't do that — and for good reason, I argued, because the corresponding graphs tend to undermine the point that they wanted to make (see "Textual narcissism", 7/13/2012; "Textual narcissism, replication 2", 7/14/2012; "What does this graph mean?", 7/13/2012; "It's all about who?", 7/31/2012).

And as I pointed out in those posts, one problem with this type of research is that almost everywhere you look in these time series of word frequencies and ratios of word frequencies, you find striking patterns.

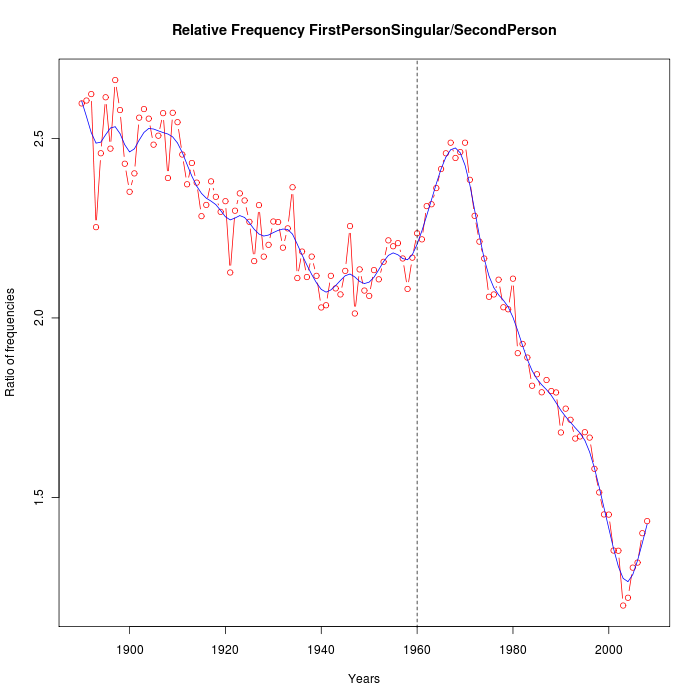

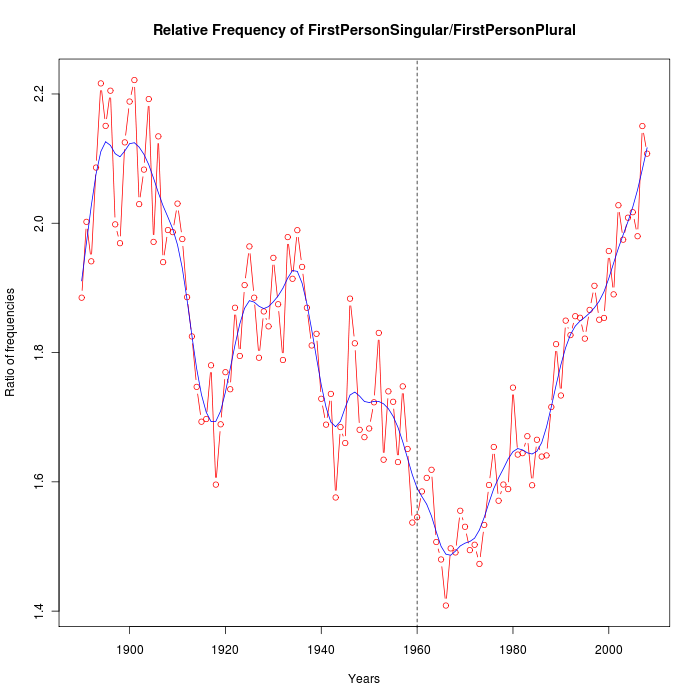

Thus since the late 1960s, American books have apparently seen a large increase in the frequency of second-person vs. first-person-singular pronouns. Does this reflect the rise of the "you generation", interested more in others than in themselves? Not according to the Conventional Wisdom, which might prefer to note that over the same time period, the ratio of first-person-singular to first-person-plural pronouns has increased (though not by as large a factor), supporting the received opinion that Kids Today are getting more and more self-obsessed:

|

|

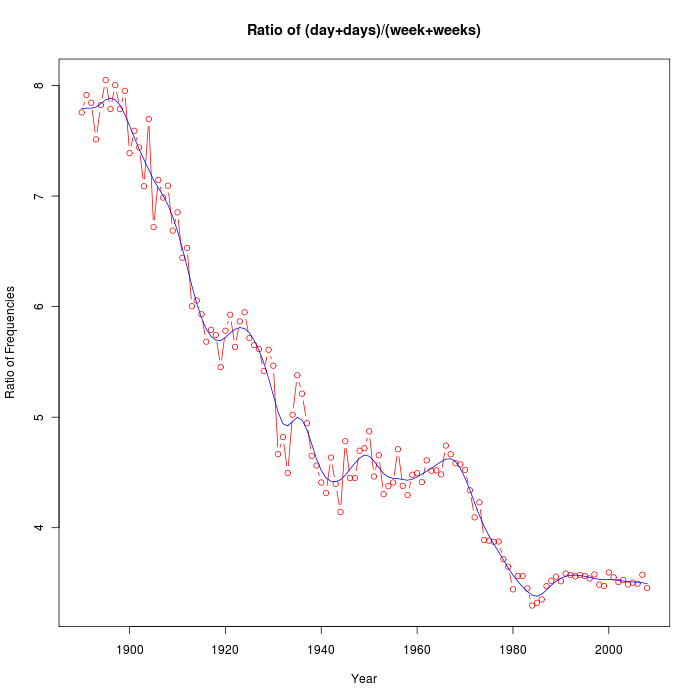

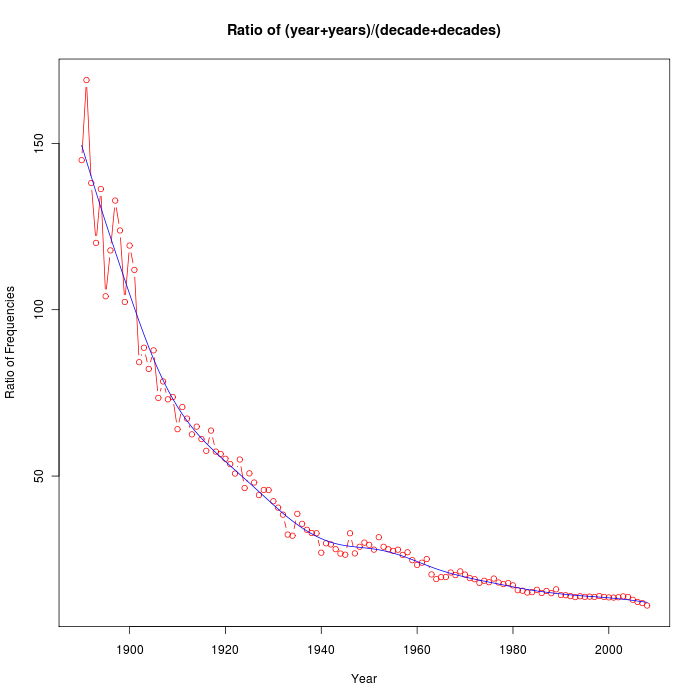

And if we pick some more-or-less random conceptual comparison — say day vs. week or year vs. decade — we're also likely to see significant (and perhaps even strikingly large) historical trends:

|

|

It's often easy to think of possible explanations — in this case, perhaps our culture is increasingly interested in longer periods of time?

But there's a serious problem looming down this road.

There are lots of English words; and even larger number of sets of words arguably related to one another in some conceptual way; and a larger-still number of plausible comparisions of pairs of such sets of words. This generates a really, really big space of possible quantitative comparisons of time series; experiments in this space are really, really easy to do; and the numbers are large enough that almost all differences are statistically "significant".

This doesn't mean that the results of such experiments are uninteresting or misleading. But it's just about the worst imaginable sort of situation from the point of view of publication bias. So be careful out there.

MattF said,

August 14, 2012 @ 11:05 am

I've generally avoided looking at 'ratio of frequencies' for analytical purposes– If you'd asked me why, I'd mumble something like "Everybody knows that the statistics of ratios are badly behaved" or "The Cauchy distribution doesn't even have a mean value." Have I been missing out on a useful quantity?

[(myl) I presume that you're not against the sort of ratios involved in normalizing subset counts in order to calculate percentages or rates of some other kind? So is there a qualitative difference between analyzing "count-of-word-X/count-of-all-words" and analyzing "count-of-word-X/count-of-word-Y"?

It's true that the former quantity is bounded between 0 and 1, whereas the latter isn't. But that's not necessarily a Good Thing — after all, the whole apparatus of logistic regression is intended to let us model numbers between -∞ and ∞ rather than 0 and 1.

In this case, I'm following the lead of the Twenge et al. paper. Leaving that work aside, what treatment do you think is appropriate for analyzing and comparing time series of word counts?]

Thom said,

August 14, 2012 @ 11:31 am

This is a good reminder that transparency of research is important in raising one's validity. I enjoy looking at corpora in my research, and feel that "more is better" in this case–because of the options and questions that it raises. Is it a genre difference? Is it a corpora selection difference? (Alternately, why are they showing similar results?) After all, it is by asking the new questions that pushes us to investigate more.

Matthew Stephen Stuckwisch said,

August 14, 2012 @ 11:31 am

If women are more present, then I think it's a safe (though not assured) bet they'll appear more in writings. Just as fifty years ago, Afganistan would have been a low frequency word but no doubt has exploded in popularity post-9/11.

Status and presence are independent things, and I'm not sure one can show reliably indicate the other. A more laborious, but perhaps better indicative of the status/views on women, might be to see the relative frequency of generalized persons being represented by a masculine or feminine referent (or both, or neutral) which traditionally would have been virtually exclusively masculine. But that would require determining if each he/she/it (and related) refers to a specific person or a general one, which would monstrously slow down analysis.

MattF said,

August 14, 2012 @ 12:18 pm

@myl

I agree that 'significance' shouldn't depend on rescaling, but that's not the same as taking the ratio of two time series. I'd be comfortable, e.g., with rescaling (or, more broadly, filtering) -all- time series under consideration the same way. Or to put it differently, if I'm going to promote one time series in a set to a 'norm' that all the others are compared to, there should be some reason for that distinction.

As for what I would use, I think the graph of frequencies that you provide shows all the interesting trends and correlations in a straightforward way. What does taking the ratio add?

[(myl) One could argue that a single line is easier to grasp visually than multiple lines are. And certainly, a single column of numbers in a table will be easier to grasp than the relation among several columns of numbers is. If you're uncomfortable with less-general scaling, how about (for example) taking the ratio of masculine 3rd-singular pronouns to the sum of masculine and feminine 3rd-singular pronouns? That's a local kind of scaling, but it can be applied in the same way to either of the two subsets being compared?]

David B said,

August 14, 2012 @ 1:10 pm

The datasets are large enough that pretty much every difference you find is statistically significant, sure, but that just underscores the reason i've been saying the last few years to anyone who will listen that those of us who work in quantitative analyses of language need to start reporting effect sizes along with our p values. They've got their own problems, yes, but at least it gives another check on whether there's actually a "there" there.

[(myl) Indeed. And not just in "quantitative analyses of language" — this applies even more strongly in economics, in social psychology, in medical research, and so on.]

Bob Moore said,

August 14, 2012 @ 1:34 pm

My guess about the rise of second person pronouns compared to first person would be the relaxation of the prescriptive rule against ever using second person in formal writing. How often do you see "one" as a pronoun these days? Or should I say, how often does one see "one" as a pronoun these days?

Ethan said,

August 14, 2012 @ 2:09 pm

@Bob Moore: I'm dubious about that line of argument, at least with regard to technical writing.

Google scholar:

"if one considers" 235,000 hits

"if you consider" 25,700 hits

"if we consider" 417,000 hits

or N-grams [link to N-grams that probably won't work]

Andy Averill said,

August 14, 2012 @ 2:19 pm

Mark, I think you're on to something with the decline in the use of "he" and "man" as gender-neutral terms. 1970 seems about right as the date after which considerable ingenuity began to be exerted not to use "he" in formal writing.

Also, If the change really reflected women's rising social status, wouldn't we see a big increase in the occurrence of female terms along with the decline in male terms? But that's not what the data show — the frequency of female terms doesn't change much.

[Indeed. The average frequency of "woman" in the last two decades of the 20th century (1980-1999) was only about 6.7% higher than in the first two decades (1900-1919). In contrast, the average frequency of "man" in the 1980-1999 period was just 49% of what it was in the 1900-1919 period.

Similarly, the average frequency of "she" in the 1980-1999 time period was only about 5.3% greater than in 1900-1911, whereas the average frequency of '"he" in 1980-1999 fell to about 64% of what it was in 1900-1911.

So in both cases, the proportional reduction in male references (about 36-51%) was much larger than the proportional increase in female references (about 5-7%). Since the number of male references starts out much higher, the difference in counts is of course much larger than the proportional difference.

I'm uncertain how important a cause the decline in the use of gender-neutral "he" and "man" is. But what's going on is clearly NOT just an increase in references to women.

Update — after fixing a bug in my code, what I said about the frequency of "she" and "woman" remains true, but we see that the frequency of "women" actually rose sharply post 1965…]

Bob Moore said,

August 14, 2012 @ 2:54 pm

@Ethan: I am not surprised that the articles indexed by Google Scholar would be the last bastion of the old rules. The broader corpus of Google ngrams seems to support my conjecture, at least as I read the data. The relative frequency of "you" and "one" in the pattern "if you X / if one Xes" depends on what the verb is. For "see", "go", "try" and "think", "you" is and always has been more frequent than "one". For "consider", "imagine", and "examine", "one" is currently more frequent. Perhaps the more formal the verb, the more likely "one" is. In all the cases I found were "one" is more frequent, however, the "if one Xes" pattern peaked in the 1970s, roughly matching the peak in Mark's overall "I/you" graph, and has been trending down since then, consistent with my conjecture.

Chris Waters said,

August 14, 2012 @ 3:20 pm

In addition to increasing use of "one" in formal writing, I think there may also be an increasing using of singular "they" in informal writing and speech.

Back in the seventies, my annoying high-school English teacher's successful attempt to get the local subway system to change their signs from saying "Each passenger must have their own ticket" to "Each passenger must have his or her own ticket" was the first major hint I ever received that maybe the English language as actually spoken didn't quite match the formal definitions we were being taught. I mean, if a large bureaucracy could manage to let the original sign get to the distribution phase without anyone noticing that "error", was it really an error?

If that particular teacher had been one of the many that I liked, rather than annoying, I might have been proud of his accomplishment, instead of being motivated to question it, and I could have grown up to be a vanilla Grammar Nazi instead of a curious student of interesting and unusual usage. So I guess I have to thank him for that. :)

Ethan said,

August 14, 2012 @ 6:18 pm

@Bob Moore: Sorry, I wasn't clear. My thought was not to dispute the decline of "one", but to point out that in technical writing it is [more?] likely to be replaced by "we" than by "you". I would have expected, rightly or wrongly, that if the decline in "one" changed the overall balance of first/second person pronoun usage at all it would boost the first person for this reason.

Rubrick said,

August 14, 2012 @ 6:29 pm

The opening sentence of the abstract, baldly asserting a fact about changes in women's status during the 20th century as though it were so obvious that it needs no analysis itself, really bothers me. In this case their assertion is probably broadly true, but it still seems far from above debate.

Try replacing "The status of women" with "The level of self-absorption" — had they started a paper that way, it would clearly be a case of assuming what they set out to prove.

Theophylact said,

August 14, 2012 @ 6:59 pm

Too many "-omics" already.

[(myl) You're a few years late to this party. Do you have similar concerns about -ologies, -ons, -oses, and so on?]

Andrew (not the same one) said,

August 15, 2012 @ 6:26 am

Rubrick: I think the first sentence is meant to be read in conjunction with the later reference to 'indicators of U.S. women’s status such as educational attainment, labor force participation, and age at first marriage'. The authors take the shifts in women's status to be already established by measures of this kind. (The first paragraph of the actual paper bears this out.) They are not trying to infer changes in women's status from linguistic data; they are investigating whether the linguistic data correlates with the already known facts about changes in women's status.

Mark Young said,

August 15, 2012 @ 10:24 am

I'm wondering if there mightn't be an error in your man/men/woman/women chart. The number for "women" seems to be zero right thru. Google n-grams shows similarly shaped curves for the first three terms, but shows "women" as about level with "woman" (around 100-200 ppm) till about 1970. (Also n-grams shows "woman" above both "man" and "men" in the 1990s. Presumably the datasets are a bit different….)

Mark Young said,

August 15, 2012 @ 10:29 am

(Oops. It's "women" that was above "man" and "men", not "woman".)

NW said,

August 15, 2012 @ 12:05 pm

There was something wrong with Ngram Viewer about the time this post first appeared. I checked and got zero uses for 'women' in American English, as in the graph above, and some other anomalies (no option to search Google Books for some of the words in some of the corpora), which eventually all went away after I went back and forth between the corpora. I've never seen this error on the Ngram Viewer before.

[(myl) The data in my graph didn't come from the Google Ngram Viewer, but from the underlying numbers in the American English dataset. But there WAS a bug in my code, which I've now fixed — thanks for pointing it out to me. I'll post my data and code within a few hours, when I have a couple of minutes.

The correct plot shows an interesting fact, which is that "woman" didn't change very much post 1965, but the frequency of "women" rose sharply.]

Bob Moore said,

August 15, 2012 @ 1:21 pm

@Ethan: Ah, point taken. Certainly in my own academic writing, I avoid both "one" and "you", and use "we" extensively. However, in newspapers, magazines, and non-academic books, which would have at one time also been written in a more formal register, I conjecture that "you" is more common than previously. Also, I think the type of writing you are thinking of is better termed "academic" than "technical". For example, every technical book description I have looked at on the O'Reilly web site has "you" all over the place.

H Klang said,

August 15, 2012 @ 11:35 pm

Having a very large database doesn't increase the probability that a randomly chosen measurement will be statistically significant. On the ergodic principle, I would expect that this probability tends to 5% as the size of the population goes to infinity (according to the definition of statistically significant that I know). On the other hand, a large database does guarantee a steady and reliable supply of such false positives, as opposed to chancy and challengeable. In fact 5% should please anybody nowadays if it can be relied upon.

J.W. Brewer said,

August 16, 2012 @ 8:55 am

Rubrick/Andrew: It is difficult for me to suppress the suspicion that the measure for "status of women" (which presumably necessitates semi-arbitrary weightings of a bunch of semi-arbitrarily chosen measures) was to some extent cherry-picked to fit their graph about pronouns. I mean, really, things were going consistently backwards such that women were worse off in 1952 than 1945 then worse off in 1959 than 1952 then worse off in 1966 than 1959 and only then did things suddenly turn around? How plausible is that if you step back and consider it as a historical claim from a macro level? Because that's what you would seem to need to match the graph.

Or is it a second-order thing where the rate of progress in the status of women slowed compared to the pre-1945 period but did not actually reverse? But how would you expect that to be reflected in pronoun usage? There is I suppose a further difference depending on whether you think of changes in the status of women as absolute improvement versus a zero sum game vis-a-vis men. So for example, over the period from 1920 to 1960, the percentage of young American women attending college might have increased steadily (as did the percentage of young American men) but the female-male ratio might have varied – with a predictable spike ("increased female status"?) during WW2 because so many young men were off fighting instead and then a corresponding trough ("decreased female status"?) thereafter when those men all returned plus had G.I. Bill funding. But the notion that "educational attainment" for women in general was lower in any absolute sense in 1960 than in 1920 seems highly counterintuitive.