Texting and language skills

« previous post | next post »

There's a special place in purgatory reserved for scientists who make bold claims based on tiny effects of uncertain origin; and an extra-long sentence is imposed on those who also keep their data secret, publishing only hard-to-interpret summaries of statistical modeling. The flames that purify their scientific souls will rise from the lake of lava that eternally consumes the journalists who further exaggerate their dubious claims. Those fires, alas, await Drew P. Cingel and S. Shyam Sundar, the authors of "Texting, techspeak, and tweens: The relationship between text messaging and English grammar skills", New Media & Society 5/11/2012:

There's a special place in purgatory reserved for scientists who make bold claims based on tiny effects of uncertain origin; and an extra-long sentence is imposed on those who also keep their data secret, publishing only hard-to-interpret summaries of statistical modeling. The flames that purify their scientific souls will rise from the lake of lava that eternally consumes the journalists who further exaggerate their dubious claims. Those fires, alas, await Drew P. Cingel and S. Shyam Sundar, the authors of "Texting, techspeak, and tweens: The relationship between text messaging and English grammar skills", New Media & Society 5/11/2012:

The perpetual use of mobile devices by adolescents has fueled a culture of text messaging, with abbreviations and grammatical shortcuts, thus raising the following question in the minds of parents and teachers: Does increased use of text messaging engender greater reliance on such ‘textual adaptations’ to the point of altering one’s sense of written grammar? A survey (N = 228) was conducted to test the association between text message usage of sixth, seventh and eighth grade students and their scores on an offline, age-appropriate grammar assessment test. Results show broad support for a general negative relationship between the use of techspeak in text messages and scores on a grammar assessment.

Some of the journalists who will fuel the purifying flames: Maureen Downey, "ZOMG: Text-speak and tweens: Notso gr8 4 riting skillz", Atlanta Journal-Constitution; Sarah D. Sparks, "Duz Txting Hurt Yr Kidz Gramr? Absolutely, a New Study Says", Education Week; Mark Prigg, "OMG: Researchers say text messaging really is leading to a generation with poor grammar skills", The Daily Mail; Gregory Ferenstein, "Texting Iz Destroying Student Grammar", TechCrunch; the anonymous author of "Texting tweens lack 'gr8' grammar", CBC 7/26/2012; … And, of course, in a specially-hot lava puddle all his own, the guy who wrote the press release from Penn State: Matt Swayne, "No LOL matter: Tween texting may lead to poor grammar skills", 7/26/2012.

What did Cingel and Sundar actually do? If you're in a rush, let's cut to the crucial table, and their explanation of it:

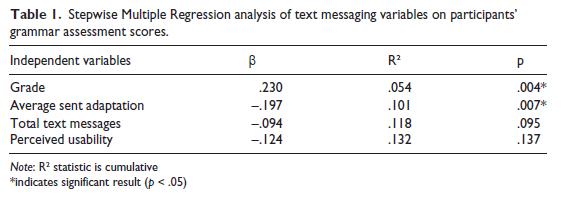

In order to better understand the variance in grammar assessment scores, predictor variables were tested as part of a stepwise multiple regression model. Specifically, four variables were tested in the following order: grade, average amount of sent message adaptation, total number of text messages sent and received, and perceived utility of text messaging. The average number of message adaptations in received text messages was excluded from this model due to this variable’s multicollinearity, or high correlation, with average sent text message adaptation. This analysis yielded two statistically significant predictors of grammar scores: grade (β = .23, p < .01) and average sent message adaptation (β = -.20, p < .01). Neither total number of text messages (β = -.09, p = .10) nor perceived utility (β = -.12, p = .14) were found to be significant predictors.

("Grade" is 6th, 7th, or 8th; and "sent adaptation" refers to the students' self-report of how often they used various texting-associated writing conventions in texts that they sent.)

I want to point out three things about this table:

- The "Average sent adaptation" explained 4.7% of the variance in grammar scores (0.101-0.054 = 0.047). This is a pitifully small effect.

- "Grade" explained a bit more of the "grammar assessment" variance (5.4%) They actually tell us what the average "grammar assessment" scores by grade were, and also what the variances were: "Sixth graders scored a mean of 17.26 (SD = 3.11), seventh graders scored a mean of 17.92 (SD = 2.74), and eighth graders scored a mean of 18.27 (SD = 2.66)". Thus Grade accounted for at most about one question's worth of variation (on a 22-question test), and so "Average sent adaptation" accounted for somewhat less than that. Alternatively, if we take the variance remaining after Grade was taken out to be about equal to the square of the standard deviation of the per-grade scores (about 3^2 = 9), then 4.7% of that variance is about half a question.

- Their survey collected at least 20 independent variables, relating to texting and to other things like television and music consumption. Apparently none of these had a statistically-significant effect except for that "sent message adaptation" measure. It would be very surprising, in a collection of this size and complexity, NOT to find at least one predictor variable that accounted for about 5% of the variance in a vector of random numbers.

OK, if you've got some time, here are the details. They looked at middle-schoolers in one school:

Participants were sixth, seventh, and eighth grade middle school students from a midsized school district on the east coast of the United States. English teachers were approached prior to the beginning of the study and asked to volunteer class time. […] In all, 542 surveys were administered to students in the classroom; 228 completed surveys were returned, for a response rate of 42.1 percent. Of this final sample, 36.8 percent were from sixth grade (N = 84), 21.5 percent from seventh grade (N = 49), and 41.7 percent were from eight grade (N = 95). Ages ranged from 10 to 14, with a mean of 12.48. Males represented 39.1 percent of the final sample. […]

Aside from grade-level and age, their independent variables fell into three general groups. The first was "usage" of text messaging, along with other life-style factors:

Adolescents were first asked to think about their average day and record the time they spend using a variety of technologies. Importantly, participants were asked to self-report the number of text messages they send and receive on an average day. In addition, respondents were asked to indicate the amount of time they spend studying, watching television, listening to music, and reading for pleasure. Finally, they were asked for the amount of free time they have each day. Answers were reported with a number which indicated the average amount of time spent engaging in each activity or the average number of sent and received text messages. Adolescents reported receiving 46.03 (SD = 83.61) and sending 45.11 (SD = 85.24) text messages per day.

The second was "attitudes" towards text messaging:

Next, the survey asked adolescents to record their attitudes toward text messaging by using a 5-point Likert-type scale, where an answer of 1 indicated that the respondent strongly disagreed and an answer of 5 indicated strong agreement. They were asked questions regarding the convenience and overall utility of the technology, such as ‘The speed of text messaging makes it convenient to use.’ Questions were also included to determine if an adolescent’s use of these technologies is primarily driven by parents or friends.

And the third was "textual adaptation" in text messaging:

The independent variable of sent and received message adaptation was assessed by asking participants to self-check their last three sent and their last three received text messages to separate individuals and record the number of adaptations present in each text message. This was done to ensure greater generalizability by including a wider range of messages, with a wider range of text message length. Also, it increased the chances of the text messages involving different groups of individuals, such as friends, parents, or siblings. For each of the three received text messages, participants were asked to list their relationship to the sender. This was also done for each sent text message. Participants then self-reported the number of adaptations they found in each text message and classified a given adaptation into one of five categories. The five categories of common text message adaptation identified in the survey were use of abbreviations or initialisms, omission of non-essential letters, substitution of homophones, punctuation adaptations, and capitalization adaptations.

Note, again, that this gave them a very large number of factors to work with, which is always helpful if you're determined to find a "statistically-significant" effect, and you don't plan to do any correction for the implicit multiple comparison.

Their dependent measure was

… a 22-item diagnostic grammar assessment instrument. This assessment was adapted from a ninth-grade grammar review test. The test was reviewed to ensure that students had been taught all of the concepts covered in this assessment by sixth grade so that the same version of the grammar assessment could be administered to all three grades. This was done so that adolescents’ scores could be compared to one another across grades. […] Sixth graders scored a mean of 17.26 [out of 20] (SD = 3.11), seventh graders scored a mean of 17.92 (SD = 2.74), and eighth graders scored a mean of 18.27 (SD = 2.66).

Curiously, the version of the "Grammar Assessment" that they present as Appendix A has only 20 questions on it, but never mind that. And the questions on that test generally have very little to do with "grammar" in the traditional sense of that word, but never mind that for now either.

Aside from the problem that the effect was so small as to be effectively meaningless, I have some qualms about the way they collected the data:

Participants were introduced to the study by way of an opening statement in their classroom. After this was completed, they were given a grammar assessment, which was completed during class time. The grammar assessment lasted about 10 minutes. Once it was completed, participants handed in the grammar assessments and were in turn given a survey to complete at home. Attached to the take-home survey was a letter to parents, informing them about the procedure of the study, and seeking their informed consent by way of a signature for their child’s participation in this research. […] Participants were told about the types of questions that they would need to answer on the survey and given time to begin completing the survey during class time, at the teacher’s discretion. Participants were informed that they were to think of their average day when completing questions regarding their media use. Finally, those who did not use a certain technology were told only to answer questions that applied to the technologies they have used. They were also given the opportunity to ask any questions they may have. Participants were given one week to return the completed surveys to class. After one week, surveys were collected and participants were verbally notified in the classroom about the study’s completion. Take-home surveys were linked to the grammar assessments through the use of unique identification codes. […]

First, I will bet that the participants inferred (if they weren't explicitly told) that the study aimed to show that texting impacted their "grammar"; this could easily lead to a small bias in self-reporting of texting practices, based on their impression of their abilities in spelling, punctuation, etc.

And second, as recently discussed here, at least some current teens "are scornful of txt-speak abbreviations, and see them as something that clueless adults do", while others clearly make extensive use of these "adaptations". What was the ethnography of these attitudes in the school Cingel and Sundar studied? Was there an association with age? With sex? With socio-economic status? With race? With whatever form the "jocks vs. burnouts" opposition takes in that community?

I'll also note that this paper's bibliography curiously lacks a fairly long list of well-known and obviously-relevant publications in this area, which generally come to opposite conclusions. A few of them are listed below, with their abstracts:

Beverly Plester, Clare Wood, and Puja Joshi, "Exploring the relationship between children's knowledge of text message abbreviations and school literacy outcomes", British Journal of Developmental Psychology, March 2009.

This paper presents a study of 88 British 10–12-year-old children's knowledge of text message (SMS) abbreviations (‘textisms’) and how it relates to their school literacy attainment. As a measure of textism knowledge, the children were asked to compose text messages they might write if they were in each of a set of scenarios. Their text messages were coded for types of text abbreviations (textisms) used, and the ratio of textisms to total words was calculated to indicate density of textism use. The children also completed a short questionnaire about their mobile phone use. The ratio of textisms to total words used was positively associated with word reading, vocabulary, and phonological awareness measures. Moreover, the children's textism use predicted word reading ability after controlling for individual differences in age, short-term memory, vocabulary, phonological awareness and how long they had owned a mobile phone. The nature of the contribution that textism knowledge makes to children's word reading attainment is discussed in terms of the notion of increased exposure to print, and Crystal's (2006a) notion of ludic language use.

Nenagh Kemp, "Texting versus txtng: reading and writing text messages, and links with other linguistic skills", Writing Systems Research 2(1) 2010:

The media buzzes with assertions that the popular use of text-message abbreviations, or textisms (such as r for are) is masking or even causing literacy problems. This study examined the use and understanding of textisms, and links with more traditional language skills, in young adults. Sixty-one Australian university students read and wrote text messages in conventional English and in textisms. Textism messages were faster to write than those in conventional English, but took nearly twice as long to read, and caused more reading errors. Contrary to media concerns, higher scores on linguistic tasks were neutrally or positively correlated with faster and more accurate reading and writing of both message types. The types of textisms produced, and those least well understood by participants, are also discussed.

M.A. Drouin, "College students' text messaging, use of textese and literacy skills", Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 2011:

In this study, I examined reported frequency of text messaging, use of textese and literacy skills (reading accuracy, spelling and reading fluency) in a sample of American college students. Participants reported using text messaging, social networking sites and textese more often than was reported in previous (2009) research, and their frequency of textese use varied across contexts. Correlational analyses revealed significant, positive relationships between text messaging frequency and literacy skills (spelling and reading fluency), but significant, negative relationships between textese usage in certain contexts (on social networking sites such as MySpace™ and Facebook™ and in emails to professors) and literacy (reading accuracy). These findings differ from findings reported in recent studies with Australian college students, British schoolchildren and American college students. Explanations for these differences are discussed, and future directions for research are presented.

Clare Wood, Sally Meachem, Samantha Bowyer, Emma Jackson, M. Luisa Tarczynski-Bowles, and Beverly Plester, "A longitudinal study of children's text messaging and literacy development", British Journal of Psychology. August 2011:

Recent studies have shown evidence of positive concurrent relationships between children's use of text message abbreviations (‘textisms’) and performance on standardized assessments of reading and spelling. This study aimed to determine the direction of this association. One hundred and nineteen children aged between 8 and 12 years were assessed on measures of general ability, reading, spelling, rapid phonological retrieval, and phonological awareness at the beginning and end of an academic year. The children were also asked to provide a sample of the text messages that they sent over a 2-day period. These messages were analyzed to determine the extent to which textisms were used. It was found that textism use at the beginning of the academic year was able to predict unique variance in spelling performance at the end of the academic year after controlling for age, verbal IQ, phonological awareness, and spelling ability at the beginning of the year. When the analysis was reversed, reading and spelling ability were unable to predict unique variance in textism usage. These data suggest that there is some evidence of a causal contribution of textism usage to spelling performance in children aged 8–12 years. However, when the measure of rapid phonological retrieval (rapid picture naming) was controlled in the analysis, the relationship between textism use and spelling ability just failed to reach statistical significance, suggesting that phonological access skills may mediate some of the relationship between textism use and spelling performance.

Also relevant (and also missing from the bibliography) is David Crystal's Txtng: The Gr8 Db8 (2008), discussed on Language Log in "Shattering the Illusions of Texting", 9/18/2008, "Menand on Linguistic Morality", 10/22/2008, and "Bad Language", 10/28/2008.

Finally, I need to remind everyone that texting-style abbreviations destroyed the Roman Empire: "pont max tr pot lol", 3/24/2008. As Catullus warned us, "coartatio et reges prius et beatas / perdidit urbes."

Mike said,

August 2, 2012 @ 6:49 am

I am very relieved to see that Jonathon Edwards has been reincarnated as Dr. Liberman.

[(myl) Great Awakening FTW! Though I identify more with George Whitefield.]

Dean Foster said,

August 2, 2012 @ 6:49 am

Wow! Wonderful post!

I love the connection to the young people are scornful of txt-speak idea. That is a wonderful lurking variable to explain what little effect was found. Probably as often is found in this sort of study it is just another proxy for income / parental education.

Andy Averill said,

August 2, 2012 @ 8:18 am

"an extra-long sentence is imposed on those who also keep their data secret" — I would have thought that was the most appropriate punishment for those who commit sins of the Flesch…

Sivi said,

August 2, 2012 @ 8:42 am

I agree with the extra fires for Swayne. "No laughing-out-loud matter" isn't a phrase anyone uses, and suggests that Swayne doesn't understand the usage of that acronym.

Actually, most of those headlines are pretty painful to read.

KeithB said,

August 2, 2012 @ 9:05 am

There really needs to be a consensus about increasing the required p-value when you shotgun a study like this with numerous variables. One wonders whether the authors even know that if you have 20 variables there is a good chance that random variations (especially with small sample size) will get you a "hit", especially at p=.05.

[(myl) You're right; but in general I'm much more concerned about one of Deirdre McCloskey's "Secret Sins of Economics", namely "testing statistical significance without a loss function". Or, to put it in more intuitive terms, focusing on "statistical significance" when the context requires attention to practical significance. Quoting McCloskey:

Economics has fallen for qualitative “results” in “theory” and significant/insignificant “results” in “empirical work.” You can see the similarity between the two. Both are looking for on/off findings that do not require any tiresome inquiry into How Much, how big is big, what is an important variable, How Much exactly is its oomph. Both are looking for machines to produce publishable articles.[…] Bad science—using qualitative theorems with no quantitative oomph and statistical significance also with no quantitative oomph—has driven out good.

As she notes, similar sins "cripple the scientific enterprise" in other fields as well.

And in this case as in many others, there's also the question of what unmeasured variables a given factor might be a proxy for…]

Josef Fruehwald said,

August 2, 2012 @ 10:19 am

I had a much more knee-jerk reaction post, and uncharacteristically didn't get into the stats too much: http://val-systems.blogspot.com/2012/07/teens-and-texting-and-grammar.html

But really, no quantitative method can overcome crap measures. If the self-report data explained 50% of the variance on their "Grammatical Assessment", I still don't think I'd be swayed.

Another relevant paper on txtisms is Sali Tagliamonte and Derek Denis (2008) "Linguistic Ruin? LOL! Instant Messaging and Teen Language." in American Speech. They were examining instant message data, and one of their big results from the conclusions was:

"In a million and a half words of IM discourse among 71 teenagers, the use of short forms, abbreviations, and emotional language is infinitesimally small, less than 3% of the data."

SeaDrive said,

August 2, 2012 @ 10:20 am

"Adolescents reported receiving 46.03 (SD = 83.61) and sending 45.11 (SD = 85.24) text messages per day."

I'm wondering if they charged into a multivariate regression that assumes this to be a normal distribution.

[(myl) It's not clear — they don't provide their code either.]

malkie said,

August 2, 2012 @ 11:28 am

@Josef Fruehwald

"In a million and a half words of IM discourse among 71 teenagers, the use of short forms, abbreviations, and emotional language is infinitesimally small, less than 3% of the data."

I wonder if the half word was an IM abbrev – LOL.

Sybil said,

August 2, 2012 @ 1:12 pm

That "Grammar Assessment" is beyond bizarre. (Or maybe I am too long out of school and unused to such things.) I am particularly looking at items 15-20.

It's also bizarre in that it doesn't seem to be checking for the sort of "grammatical" mistakes one might expect to see if the use of textese really did have the influence claimed, except possibly in a few questions (if we assume that confusing homophones is one effect). Very puzzling choice.

mollymooly said,

August 2, 2012 @ 2:49 pm

"It would be very surprising, in a collection of this size and complexity, NOT to find at least one predictor variable that accounted for about 5% of the variance in a vector of random numbers."

Indeed. As usual, xkcd explains.

William Steed said,

August 2, 2012 @ 5:44 pm

I'm glad Josef Fruehwald has piped in there. I was going to give a similar point of view, but without the reference. With predictive text functions and free texting plans, most of the texts I send, receive and see online (sites like AutoCowrecks and damnyouautocorrect) have very little reduced spelling. Some have terrible garmmra (and even grammar), but it's not abbreviation. That throws off all of these results in the first place.

(Mental note: publishing really popular linguistic research may result in being excoriated on LLog).

Daniel Barkalow said,

August 2, 2012 @ 6:13 pm

Surely, Catullus warned us "co'rt'ti' et reges prius et beatas / predidit urbes." But that was after his girlfriend's phone autocorrected "amor passes" (typo for passus) to "amor passeris", leading Catullus to write a heart-felt but quite misguided poem, so we can't really trust his position on such devices.

Andy Averill said,

August 2, 2012 @ 7:51 pm

@Daniel Barkelow, was he texting while driving his Prius? That might explain it.

Andy Averill said,

August 2, 2012 @ 7:52 pm

*Daniel Barkalow

Dan H said,

August 3, 2012 @ 6:51 am

I noticed that as well. I'm not sure *I* would get some of those questions right, just because I have no idea which stupid "grammar" rules they're supposed to be testing.

Going down the list: Question 8 requires the candidate be familiar with the phrase "excepted from the list" which feels extremely unnatural to me.

16 is clearly "incorrect" but I don't know what I'm supposed to be calling it incorrect for – the use of a comma in place of a semicolon, or placing the exclamation mark outside the quotation marks.

17 is either right or wrong depending on your feelings about the Oxford Comma.

19 is either right or wrong, depending on whether you're supposed to be picking up on the fact that New York isn't capitalised (which strikes me as stretching your definition of "grammar" very, very thin).

[(myl) That "grammar assessemnt" is indeed a curious document. It's even possible that students with a better command of the standard written language might in some cases get *lower* scores on that test.]

Ryan said,

August 3, 2012 @ 10:51 am

About the discrepancy between reported items on the grammar test, and the number of apparent items, it looks like there are 2 items in 7 and 8.

Steve Kass said,

August 3, 2012 @ 2:09 pm

The Los Angeles Times has an embarrassing piece on this today. [link]

Among other things, it says that incorrect is the right answer to "Worried, and frayed, the old man paced the floor waiting for his daughter. (Correct/Incorrect)"

Not, however, because of the (very debatably) spurious comma. Apparently it's wrong because "frayed" should be "afraid." WTF?

Dan Hemmens said,

August 3, 2012 @ 4:42 pm

To be fair, it is certainly true that "f-r-a-y-e-d" is not the correct way to spell the word "afraid".

It sounds stupid, but I could not put my hand on my heart and swear that this isn't the intended answer. There are other questions on the test which ask the candidate to choose between two equally acceptable versions of the same sentence, and I wouldn't put it past the people who designed the test to try to test a candidate's "ability" to "distinguish" between two words which were both perfectly acceptable in the context.

It also strikes me as an excellent response to all five of the last three questions: "this sentence is incorrect, because it says new york when it should say Boston".

Steve Kass said,

August 3, 2012 @ 6:52 pm

In the apparent source for this study's questions, http://bit.ly/MVsGXt the "frayed" question is as follows:

Add the proper punctuation to the following sentences:

11. Worried and frayed the old man paced the floor waiting for his daughter

Unfortunately, while the study questions appear in an Appendix of the paper in question, the answers don't.

Jens Fiederer said,

August 7, 2012 @ 4:48 pm

> Unfortunately, while the study questions appear in an Appendix of the

> paper in question, the answers don't.

Perhaps wisely – disagreements on the answers would cast extra shadows on the reputations of the authors.

This Week’s Language Blog Roundup: Mars, Olympics, and more | Wordnik said,

August 10, 2012 @ 10:00 am

[…] Language Log, Victor Mair addressed all the single ladies in Chinese, and Mark Liberman considered texting and language skills and some journalistic unquotations (Electric Lit rounded up seven more unquotationers). At […]

Link love: language (45) « Sentence first said,

August 15, 2012 @ 12:51 pm

[…] Teens and texting and grammar. […]

Sorry, but I’m not Convinced Texting is Destroying English Grammar « Grammar Pedagogy for Writing Teachers said,

September 15, 2012 @ 12:14 am

[…] linguist Mark Lieberman points out a number of serious flaws in C & S’s methodology and their statistical analysis. I […]

OMGWTF writing fail? | Stats Chat said,

September 22, 2012 @ 2:29 am

[…] Texting and language skills […]

Cong ty duoc pham said,

March 20, 2013 @ 3:57 am

Perhaps wisely – disagreements on the answers would cast extra shadows on the reputations of the authors.

tranh son dau said,

June 8, 2013 @ 2:04 pm

I love the connection to the young people are scornful of txt-speak idea. That is a wonderful lurking variable to explain what little effect was found.