Textual narcissism

« previous post | next post »

Tyler Cowen, "I wonder if this is actually true", Marginal Revolution 7/12/2012.

Researchers who have scanned books published over the past 50 years report an increasing use of words and phrases that reflect an ethos of self-absorption and self-satisfaction.

"Language in American books has become increasingly focused on the self and uniqueness in the decades since 1960,” a research team led by San Diego State University psychologist Jean Twenge writes in the online journal PLoS One. “We believe these data provide further evidence that American culture has become increasingly focused on individualistic concerns.”

Their results are consistent with those of a 2011 study which found that lyrics of best-selling pop songs have grown increasingly narcissistic since 1980. Twenge’s study encompasses a longer period of time—1960 through 2008—and a much larger set of data.

That 2011 study was not very convincing — for details, see "Lyrical Narcissism?", 4/9/2011; "'Vampirical' hypotheses", 4/28/2011; "Pop-culture narcissism again", 4/30/2011; "Let me count the ways", 6/9/2011.

On the face of it, however, the new study (Jean M. Twenge, W. Keith Campbell, and Brittany Gentile, "Increases in Individualistic Words and Phrases in American Books, 1960–2008", PLoS One 7/10/2012) looks more plausible. But I thought that for this morning's Breakfast Experiment™ I'd take a closer look. And what I found diverges pretty seriously from the conclusions of the cited paper.

First, a serious complaint to the editors of PLoS One — the Twenge et al. study doesn't, as far as I can tell, provide access to its data! This is completely inexcusable, in my opinion — everything is based on two 20-by-49 tables of numbers, which could trivially have been put in the (digital-only) "paper", or (better) made available on line as separate files.

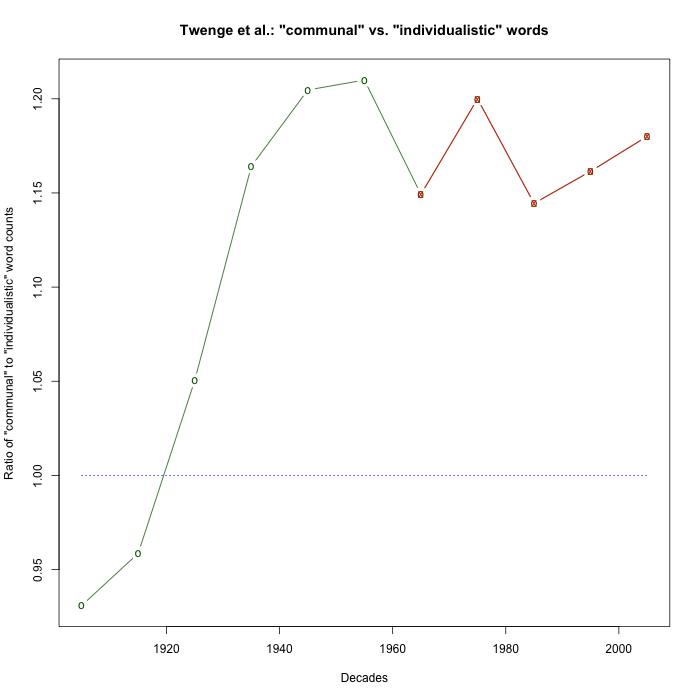

So for my replication, I had to go back to the sources. As long as I had to do that, I thought I'd do it a bit differently. First, I looked at changes from 1900 to 2010; second, I looked at the data decade-by-decade rather than year-by-year; and third I'll present the initial results graphically rather than relying on regression parameters. The results left me skeptical about what would happen in a more careful overall check. Details follow, but for an up-front taste, here's a plot of the ratio of counts of "communal" words to "individualistic" words in the American English Google Books corpus, decade-by-decade since 1900:

If Twenge et al. are right, then the last five data points — the numbers from the 1960s to the present, plotted in red — should show an relative increase in the use of individualistic words. That is, the "communal"/"individualistic" ratio should be going down.

OK, now to the details.

Twenge et al. did two experiments, one on isolated word counts and one on counts of phrases. They selected their lists of words and phrases by asking "turkers":

We used a two-step process to create a sampling of individualistic words. One sample generated words characteristic of individualism, and another rated which were most representative of the concepts. We used the same method to generate communal words.

For both phases, we recruited participants through the online service MTurk, in which participants are paid small amounts to complete various tasks. MTurk samples are typically more diverse in age and ethnicity than college samples or even most other Internet samples, and the data generated meet psychometric standards. […]

In the generation phase, MTurk participants generated words characteristic of individualism and communalism. Participants were given the following instructions: “We are looking for examples of single words often used in American culture, now and in the past, that express either: A) individualism (defined as focusing on the self and the needs of the self) or B) communalism (defined as focusing on groups, the society, and/or social rules).” Participants were then asked to list five individualistic and five communal words. Eliminating duplicates and foreign words left a list of 105 individualistic words and 137 communal words. We took a conservative approach to similar words, eliminating only plurals (for example, keeping “group” but not “groups”) but retaining noun and adjective forms, as they may have slightly different meanings (for example, “tribe” and “tribal”).

A separate sample of 55 MTurk participants rated the individualistic words on a 1 to 7 scale (with 1 = “not at all Individualistic” and 7 = “very individualistic”). Fifty-one other participants rated the communal words on a 1 to 7 scale (with 1 = “not at all communal” and 7 = “very communal”). Demographic information was not collected on participants in the second phase.

The 20 top-rated individualistic words were: independent, individual, individually, unique, uniqueness, self, independence, oneself, soloist, identity, personalized, solo, solitary, personalize, loner, standout, single, personal, sole, and singularity. The 20 top-rated communal words were: communal, community, commune, unity, communitarian, united, teamwork, team, collective, village, tribe, collectivization, group, collectivism, everyone, family, share, socialism, tribal, and union.

I worry a bit that this method means that the study is not so much focused on underlying changes in American individualistic vs. communal thinking, as on changes in American usage of words chosen by the current generation of Americans as descriptive of individualistic vs. communal thinking. But whatever — for my replication, I used the same lists of 20 "individualistic" and 20 "communal" words.

I took decade-by-decade counts, for decades starting from 1900-1909 and ending with 2000-2009, from the BYU interface to the published Google Books "American English" ngram collections. Here are links to the resulting "individualistic" and "communal" tables. (Note that the Google Books datasets preserve case, so the count for e.g. "independent" does not include counts for "Independent" or "INDEPENDENT" or etc. On a quick scan, I didn't see anything in the Twenge et al. paper about whether they did case-independent counts or not…)

These are word counts (or really, string counts) — and the overall number of words in the Google Books dataset increases over time, so we need to normalize them. I couldn't find decade-by-decade word counts for the Google Books "American English" dataset, and didn't feel like taking the time to calculate them from the year-by-year counts, so as a quick proxy I used the decade-by-decade counts for the string "The" from the same collection.

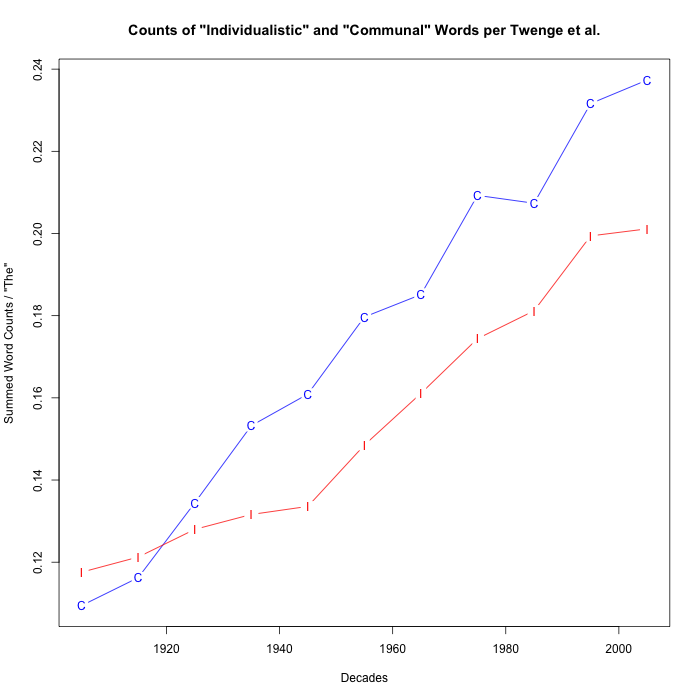

For the plot below, I've summed the counts for the 20 "individualistic" and 20 "communal" words, decade by decade. The "individualistic" word counts are plotted as a red line with "I" data points; the "communal" words are the blue line with "C" data points. The x-axis gives the mid-points of decades, e.g. 1905 for 1900-1909, etc.

Here's the R script that made the plot. Note that this is equivalent to the first of the two analysis strategies described by Twenge et al:

We analyzed the data using two complementary approaches. First, we simply summed usage means together, with the idea that the natural frequency of the words is relevant for assessing cultural change. In these analyses, a word used more frequently has a proportionally larger influence. In a second set of analyses, we Z-scored each word before summing so each word carried an equal weight regardless of absolute frequency.

According to their summary, the two methods had similar results:

Individualistic words increased in use in American books between 1960 and 2008. The correlation between year and the sum of the 20 individualistic words was r(49) = .87, p<.001. The 20 individualistic words combined made up.096% of words in books published in 1960, and.115% of words in books published in 2008. With an SD of.0063, this is an increase of d = 3.02. We also analyzed the data by Z-scoring each word before summing them. The correlation between publication year and the sum of the Z-scores was r(49) = .86, p<.001 for the 20 individualistic words, very similar to the simple sum. […]

When both individualistic and communal words are included in a regression equation predicting year, only individualistic words are significant (Beta = .83, p<.001; for communal words, Beta = .05, ns). When the Z-scored sums of both the individualistic and communal words were included in a regression equation predicting year, individualistic words increased while communal words decreased (Beta = .84, p<.001; for communal words, Beta = −.15, p<.05). Thus when the common variance of being generated by a modern sample is partialled out, only individualistic words have increased since 1960.

I haven't tried the Z-score method, or any regression experiments, because my breakfast hour is over. But so far, this dataset doesn't seem to provide any sort of convincing case for the idea that "Language in American books has become increasingly focused on the self and uniqueness" (in contrast to focus on the group and shared characteristics or experiences), either over the last century or "in the decades since 1960". If anything, I suspect that you could use these numbers to build a case slightly in the opposite direction.

I don't know why this take on the subject looks so different from the results that Twenge et al. got. The next step would be to get a copy of their tables and look into things a bit more closely.

[I should note that there's also the question of why both their "individualistic" and "communal" words seem to be increasing in overall relative frequency. One possibility is that there's something wrong with my normalization-by-"The" approach — maybe the relative frequency of "The" has been gradually decreasing? Another possibility is that their word-list creation method, which relies on a sort of word-association test administered to 2012 turkers, tends to create a list of words with a high trendiness factor, which have been increasing in relative frequency over the past hundred years or so.

And the last possibility — which is the most interesting but the least likely — is that Americans have actually become increasingly obsessed, not with themselves, but with the whole self/group opposition.]

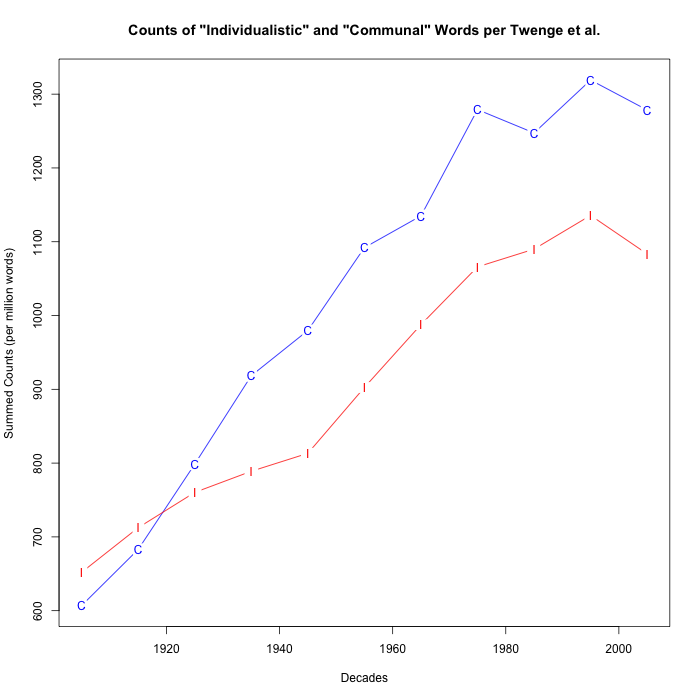

Update — I fetched the unigram counts for the Google Books American English ngram collection, and re-did the plot using those to normalize by decade. The results are not very different, except for maybe some issues with incomplete data in the last decade:

Looking at the decade-by-decade ratio of counts of "communal" words to counts of "individualistic" words, it's hard to see any serious recent trend. (Though the numbers are big enough that the increasing ratio over the past three decades (in favor of "communal" words) could probably be argued to be "statistically significant", in some sense of that so-often-meaningless phrase.) The ratio has been well above 1.0 since 1925 or so, for whatever that's worth:

Bruce Rusk said,

July 13, 2012 @ 8:33 am

Another underlying problem with methodologies like this, and with any use of the Google ngram material: is the corpus a sample of equivalent things at different points in time? In particular, might it represent a sample of different portions of "the culture" in 1900 as opposed to 2010? Literacy rates have changed, the kind of material that makes it into print has changed, and so forth (biases in what was included are yet another layer of complication). So if, for example, the early 20th corpus includes a lot of academic material and relatively little "popular" reading matter, whereas the early 21st century material is heavy on, say, genre fiction, any changes can hardly be interpreted as markers of general cultural trends.

Not to mention the issue of how these words are being used: are they being used to praise or to condemn? Of oneself/an in-group, or of others? To describe reality or an ideal? …

[(myl) True enough. And there are specific issues — thus singularity in recent years is mostly used to describe black holes or Vingean cultural acceleration, not anything really having to do with individualistic vs. communal attitudes.

But in this case as in the song-lyrics study, I don't get to the point of engaging the method, because the experimental results don't seem to work in a convincing way.]

Andy Averill said,

July 13, 2012 @ 9:14 am

Also, I'm guessing that the types of books represented in the Google Books corpus for 1900-1910 are very different from those for 2000-2010. The 1900 books were probably mostly scanned in university libraries, which tend to shed materials of ephemeral interest as time goes by. Whereas the 2000 books probably include just about everything published (physically or online) in that decade. So, more pop psychology, genre fiction, celebrity autobiographies, etc?

Rob said,

July 13, 2012 @ 9:20 am

Go to Google Books ngram viewer and enter "individual, community". You'll see what appears to be an amazing similarity in their relative frequencies. Conclusions anyone?

[(myl) In the American English collection, "individual" faded after 1970, and "community" seems to be coming up fast at the end of the race:

But it's not really fair to focus on one pair of words, out of the 20 "individualistic" and 20 "communal" words in the Twenge et al. collection.]

Victoria Simmons said,

July 13, 2012 @ 10:10 am

"And the last possibility — which is the most interesting but the least likely — is that Americans have actually become increasingly obsessed, not with themselves, but with the whole self/group opposition.]"

My subjective reaction, even before I read this, was that I know many people whom I would describe as self-oriented–focused on self-actualization, spiritual evolution, and so forth, and many of them Buddhist or Neo-Pagan in their spiritual perspective–who talk and write incessantly about community and group, or use words such as 'tribal,' with their focus remaining firmly on themselves.

But I associate that more with Boomers than with later generations. Many of my students find the spiritual paths of their hippie-ish parents or grandparents amusing, although they have inherited from them a tendency to use the words 'religious' and 'spiritual' in differing but not very reflective ways.

C Thornett said,

July 13, 2012 @ 11:05 am

Might this be an example of finding evidence to fit an assumption? Or at the least, of seeing what is looked for, just as certain journalists find a truly amazing match between their judgements of politicians and presumed features of those politicians' speech or writing?

[(myl) I guess this might be an example of failure to heed Dick Hamming's warning to "Beware of finding what you're looking for". Other possibilities: Something wrong with my version of the data; Something wrong with their version of the data; A bug in my code; A bug in their code.

If we had their data and code, it would be easier to do the forensic statistics.]

Rob said,

July 13, 2012 @ 11:18 am

Right–the two words (individual and community) may not be representative of the two semantic categories/word lists that Twenge et. al. studied. I am more interested in what seems to be very similar trends in frequency change. This demonstrates that these two words (and presumably their synonyms) are both part of a larger semantic category: social interaction (or lack thereof). Are these changes merely a result of differences in genres included in the corpus at different time periods, or do they signal a wax and wane in discussions of social interaction? The corpus creation question has to be answered before we can venture any hypotheses about culture.

Richard Bell said,

July 13, 2012 @ 1:56 pm

The main problem with the study, it seems to me, is that the two groups of words have nothing to do with self-absorption or self-satisfaction. Or rather, they have it reversed. When I use words like soloist, individual, and especially oneself I am almost certainly talking about someone else. (When I talk about myself I use the word myself: I just did.) When I use words like united, teamwork, family, share I am usually talking about myself and my belonging to a group. I don't think I have ever referred to myself as an individual or a loner.

KathrynM said,

July 13, 2012 @ 2:25 pm

I'm with Victoria Simmons and Richard Bell–I just don't see how the authors of the study can justify concluding anything about the existence of an increasing "ethos of self-absorption and self-satisfaction" from the relative occurrence of those two groups of words. I could imagine an article about planning for retirement (an arguably self-absorbed topic, for the reader at least) that used many, possibly all, of the "community" words; conversely, I could imagine an article about volunteer community outreach activities which would use most of the "individual" words.

Even as I wrote that, I realized that an article on either of the topics I just posited could fall quite plausibly in either the "self-absorbed/self-satisfied" or the (what's the opposite of "self-absorbed/self-satisfied?") "non-self-absorbed/non-self-satisfied" category. And any of the four possible articles could in fact use all 40 of the target words.

D.O. said,

July 13, 2012 @ 2:34 pm

As Bruce Rusk and others noted there are pretty obvious difficulties with interpretation even if we agree on data. That means that either the whole enterprise is bunk, or it needs to be done much more accurately, or we should go to stratospheric level of generalization. The latest approach means just looking at whether people are more interested in writing about individual or collective with the idea that if collective occupies larger (or progressively larger) part of thinking it means that there is a framework of thinking (or shifting of this framework) more adapted to communitarian view of the world. It wouldn't then matter whether one praises or condemns this point of view or whether one describes his own ideas or repeats (or debunks) others'. What is important is the focus of interest.

At this level of generality it is not a great stretch to just look at personal pronouns. Unfortunately, only 1st person gives a clear test. A quick view at Google Ngrams shows that there is nothing really interesting in terms of trends.

Doug said,

July 13, 2012 @ 6:01 pm

I wonder if their study results are due to the growth in the recent literature discussing the 'increase' in recent decades in individualism, independence, uniqueness, selfishness, self-obessessedness….?

MNP said,

July 14, 2012 @ 2:02 am

Wait a second… Twenge? Isn't she the person who writes about how the millenial generation is completely selfish with methodology about as questionable?

[(myl) Jean Twenge is the author of the 2007 popular book Generation Me: Why Today's Young Americans Are More Confident, Assertive, Entitled–and More Miserable Than Ever Before, and the co-author with Keith Campbell of the 2009 popular book The Narcissism Epidemic: Living in the Age of Entitlement, and she gives (presumably well-paid) popular lectures on the same topic. So I think it's fair to say that she has a certain amount of investment in the way the PLoS One study turned out.

As for the methodology of her many other published studies, you can examine them for yourself.]

Roger Lustig said,

July 14, 2012 @ 3:12 am

I think your first caveat is the critical one. Who knows what words a group of MTurkers from 1900 or 1920 would have considered to be individual-ish or communal-ish? Would they even have understood the notion that words would point in one direction or the other? Or, more to the point, what group or class of people would have understood?

And what were the characteristics of people who contributed to the corpus in those days? Same as those of today?

Assorted links — Marginal Revolution said,

July 14, 2012 @ 9:14 am

[…] 4. Does published language really show we are becoming more individualistic? […]

zbicyclist said,

July 14, 2012 @ 9:44 am

Clearly there is an abundance of information in the Google data set. Clearly also, it will take us a while to figure out how to validly analyze it without coming to superficial conclusions (perhaps in line with what the authors think is true). Thanks for your contribution to this.

zbicyclist said,

July 14, 2012 @ 10:00 am

The fact that both I and C show an upward trend (in probability across time) would seem to support the argument that these are words in current use for these concepts, and not the ones used 100 years ago for these concepts — assuming that in fact the same concepts existed 100 years ago in roughly the same way we understand them now.

[(myl) Perhaps. Or maybe there's a long trend towards more discussion of a set of topics that makes use of these words more likely. Or then again, maybe the reason is a change in the mix of books in the Google Books sample — this information has not been published, so we can't evaluate this idea. And of course it could be (and probably is) some mix of all three theories, and perhaps some others.]

Erez Lieberman Aiden said,

July 15, 2012 @ 9:10 am

Hi Mark!

This is great: loving how these sorts of abstract questions can now be argued, at least to some extent, from the data. JB and I just wanted to follow up on 2 bigger-ticket issues with the data that have already been pointed out on this thread.

First, Andy Averill is right. The data after 2000 is generally not commensurable with the data before 2000, and for precisely the reason he suggests. This is why in our original study, the examples targeted the period from 1800-2000, and did not include subsequent data. It's also why this is the default period for the Ngram Viewer. We discuss this issue more fully in the supplemental materials of the paper, III.0.1.2) [Sources of bias and error/Composition of the corpus]. The supplemental materials are available at Science together with our original paper, or at: http://bit.ly/pI3J83.

Second, Bruce Rusk's concern is a reasonable one, and, as we've noted before, it's unfortunate that we were unable to disclose the bibliography of the various n-gram corpora for legal reasons. That said, we did make a pretty useful corpus available for trying to alleviate, among other things, Bruce's concern.

Here's what we did. Google is constantly generating, and improving, a catalog which attempts to collect metadata for all recorded books based on over 100 sources of bibliographic metadata (supp. I.1. [Metadata]). This catalog was about 10 times the size of the collection that Google had actually digitized at the time we created the original ngram data. The catalog is almost certainly more representative of books as a whole. We then examined the BISAC code distribution of Google's bibliographic database over time, and created a corresponding corpus, called "English One Million". The year-over-year BISAC code distribution of Eng-1M is adjusted to match that of the bibliographic database as a whole, so that it is less likely to exhibit dramatic composition biases w.r.t. the books published in a given year. See Supp. II.3B, where the English One Million corpus is described in greater detail. This corpus can be selected at the Ngram Viewer, and the underlying data can be downloaded. We recommend that anyone publishing a result using the English ngram data repeat their analysis with "English One Million" just to make sure there are no anomalies. FWIW, there doesn't seem to be much difference for "individual, community" in "English One Million" (http://bit.ly/Mrr3Re) vs. plain old "English" (http://bit.ly/NZSoG3). Of course, BISAC-balancing in this way is far from an ideal solution, but people should know that the data is out there.

Supplemental materials for our paper: http://bit.ly/pI3J83

(Ngram users of the future: please read these before publishing using the data, otherwise you almost certainly won't know something you need to know.)

Matt Hodgkinson said,

August 6, 2012 @ 12:33 pm

Hi Mark,

If you want access to the data, please contact the authors directly. According to the data sharing policy of PLOS ONE, where I am an Associate Editor, the authors agree "to make freely available any materials and information described in their publication that may be reasonably requested by others for the purpose of academic, non-commercial research." http://www.plosone.org/static/policies.action#sharing

Matt

Fold Up Your Handkerchiefs: Books Have Gotten Less ‘Emotional,’ Study Says ← BookLady Review said,

March 25, 2013 @ 8:32 pm

[…] questioned the methodologies of such studies. In a post at Language Log, the linguist Mark Liberman wondered if that 2012 result reflected a change in words people used to describe individualistic and […]

Bøger viser færre følelser | Kiss Canaries said,

March 26, 2013 @ 6:24 am

[…] et indlæg på sprogbloggen 'Language Log' undrer lingvisten Mark Liberman sig over, om sådanne […]

Novel Data: Promise and Perils | MADE IN AMERICA said,

June 18, 2013 @ 7:50 pm

[…] that individualism and self-absorption have been on the rise since 1960 (see here and critiques here and here). Engal shows that the words I and he were about equally frequent in American books until […]

Novel data: promise and perils « The Berkeley Blog said,

June 20, 2013 @ 1:17 pm

[…] that individualism and self-absorption have been on the rise since 1960 (see here and critiques here and here). Engal shows that the words I and he were about equally frequent in American books until […]

Novel data: promise and perils - UC Berkeley (blog) - Ag2 Literary Agency said,

June 21, 2013 @ 11:38 am

[…] that individualism and self-absorption have been on the rise since 1960 (see here and critiques here and here). Engal shows that the words I and he were about equally frequent in American books until […]