China rules

« previous post | next post »

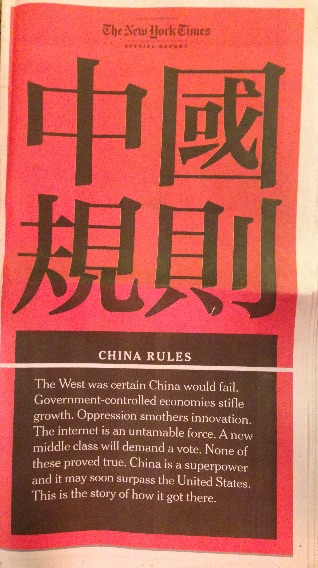

For the last few weeks, the New York Times has been running a hyped-up, gushing series of lengthy articles under the rubric "China rules". On a special section in the paper edition for Sunday, November 25, they printed this gigantic headline in Chinese characters — and made a colossal mistake:

The error also appeared on the front page of the paper:

The four huge characters (must be in the largest font size available) read:

Zhōngguó guīzé 中國規則 [note that they use traditional characters; henceforth in this post I will use simplified characters]

So the folks at NYT think that means "China rules". If we give them the benefit of the doubt and grant that they might have been trying to make a feeble pun with "rules" being intended both as a verb and as a noun, that might work in English, though with "rules" as a noun, the phrase is rather broken. Judging from the tenor of the series, however, which keeps pumping up China as hot on the heels of the United States and likely to overcome it in the not too distant future (I won't comment on their judgement in that matter), I think they mean "rules" in the verbal sense. They are trying to tell us that China is on the verge of ruling (verb), but they don't tell us the system of rules (noun) China is following in its efforts to do so.

So I think that the NYT flat out made a big, bad error. In this instance, it's not a case of Chinglish, because they were translating from English to Chinese, so it's Zhonglish.

Why do I say that the NYT made a gross error with their Chinese rendering of "China rules"? For the simple reason that guīzé 规则 cannot be a verb, only a noun, and occasionally it can act as a modifier.

Now, when we take this Zhōngguó guīzé 中国规则, which is defective as a Chinese translation of "China rules" and translate it back into English, we get "Chinese rules", which even Google Translate and Baidu Fanyi know, though Microsoft Translator renders in fractured English (for the intended meaning) as "China rules". In the construction Zhōngguó guīzé 中国规则, Zhōngguó 中国 ("Chinese") has to be the modifier and guīzé 规则 ("rules") has to be the modified, hence "Chinese rules".

I dare say that the idiomatic expression "X rules" in English, where "rules" is a verb, is most likely difficult to render effectively into many other languages.

So how should we translate "China rules (v.)" into Chinese? The simplest, crudest way is perhaps to say something like "Zhōngguó tǒngzhì 中国统治" ("China controls"), but that doesn't sound natural to me, even if we add the continuative particle "zhe 着" after the verb tǒngzhì 统治 ("rule"). Normally I would expect tǒngzhì 统治 by itself to act like a transitive verb and take an object.

If we want to express "China rules (v.)" in Chinese, not worrying about a pun that may not have been intended in the first place, then "Zhōngguó shuōle suàn 中国说了算" ("what China says counts; China has the final say; China is in charge") captures the nuance of the idiomatic "China rules (v.)" in English fairly well.

If we grant that the headline writers at the NYT were trying to make a pun with "rules" (n. and v.), then it's possible that Zhōngguó guīdìng 中国规定 might work in both senses, since — unlike guīzé 规则 ("rule"), which can only be a noun — guīdìng 规定 ("regulate; stipulate; prescribe") can be both noun and verb. However, Zhōngguó guīdìng 中国规定 ("China regulates / Chinese regulations") sounds rather aggressive, as though China were laying down the law for the rest of the world.

Bottom line: as a translation for "China rules", Zhōngguó guīzé 中国规则 grates.

[h.t. Lillian Li; thanks to Zeyao Wu, Qing Liao, and Xiuyuan Mi]

Vance Maverick said,

December 3, 2018 @ 2:03 pm

If you're determined to write something and have it translated into another language, but you don't have an independent way to judge whether the translation is good, maybe you should write straightforwardly, without punning or ambiguous idioms!

Tangentially, it's possible the intended primary meaning was as simple as "China is awesome", i.e. r00lz.

Simon McRae said,

December 3, 2018 @ 2:20 pm

I saw that on Sunday and thought, surely they mean 中国支配,

I assumed they wrote "Chinese regulations" but intended "China dominates", forgetting the two disparate uses of "rules" in English.

Steve Jones said,

December 3, 2018 @ 2:34 pm

中国说了算 is good, yes.

How about 中国当家

Carl said,

December 3, 2018 @ 2:57 pm

I find the use of traditional characters baffling. Unless they want to say Taiwan secretly makes the prescriptions? Seems like a case of sheer illiteracy.

Anne Henochowicz said,

December 3, 2018 @ 4:54 pm

When I saw that headline I thought they were playing on the noun form of rules, eg. the rules China enforces; and I also thought the traditional characters were a political statement on the legitimacy of the CCP party-state. But I have a confession to make: I only read the style section on Sundays…

Bathrobe said,

December 3, 2018 @ 6:49 pm

中國萬歲? (Long Live China! or China Banzai!)

David Marjanović said,

December 3, 2018 @ 7:32 pm

Especially in combination with the red background, which is quite likely intended to scare Americans of communism.

Ellen K. said,

December 3, 2018 @ 8:16 pm

I find the use of traditional characters baffling. Unless they want to say Taiwan secretly makes the prescriptions? Seems like a case of sheer illiteracy.

Seems like "sheer illiteracy" (in Chinese) is a reasonable possibility, which makes it not really all that baffling, in my view.

Ricardo said,

December 3, 2018 @ 8:18 pm

maybe they meant something like 'The China Model'. Surely, the NYT must have chinese-speaking staff. It's difficult to believe that the nobody ran it by them.

Ricardo said,

December 3, 2018 @ 8:23 pm

With the exception of Modern Hebrew, does any language have a serious claim to having been 'revived', even if it continues to have a museum-like existence?

Philip Taylor said,

December 3, 2018 @ 8:44 pm

Peter Berresford-Ellis lists about ten European languages that have been revived; the only one of which I am certain is Romanian, but the text is at home and I am in the office …

Chau said,

December 3, 2018 @ 9:44 pm

How about 中国称霸 ?

cliff arroyo said,

December 4, 2018 @ 3:04 am

"about ten European languages that have been revived"

In the European context 'revival' often means a return (or just entry) to public formal usage (in government, education and commerce) often in the context of a nationalist movement (like Czech). That is the languages never died out but were restricted to the private domestic sphere rather than public usage.

fev said,

December 4, 2018 @ 7:15 am

Being the Times and all, is there a chance it’s a nod to Tom Friedman’s “Hama rules”?

Rodger C said,

December 4, 2018 @ 7:50 am

I'm reminded of the notorious Irish Times headline, "Bishops Agree Sex Abuse Rules."

Philip Pan said,

December 4, 2018 @ 10:24 am

Alas, newspaper editors have a weakness for puns, and we did intend the "rules" pun. It's actually quite a common one. We published a series last year titled Trump Rules. There's a book called Harvard Rules. And of course there is the Cold War phrase Moscow Rules, which we hoped to echo with China Rules. Indeed, the text under the series name on each of the stories makes it pretty clear that it is meant to suggest that China is playing by its own rules, not just that it is ruling or dominating some unspecified arena: "They didn't like the West's playbook. So they wrote their own."

As for the translation, I should point out that The New York Times continues to publish translations and original work in Chinese on cn.nytimes.com, despite the Chinese government's continuing efforts to block the site. In general, we don't translate headlines word for word. Sometimes, it's not possible to do so in an elegant way, and often, there's just a more effective Chinese headline for a Chinese audience. In this particular case, our Chinese editors could have recommended 中国规定 and captured both the noun and verb meanings of the word rule but, as Victor suggests, that phrase didn't seem quite right. I actually very much like Victor's proposed alternative, 中国说了算, for capturing China Rules as a verb. But five characters would have presented a design challenge, and we were more interested in conveying rules as a noun. Our team settled on 中国规则 because it felt closer to the spirit of the series. To my ear, it also has a pleasant echo of a phrase I often hear from people in China discussing internal party politics, 游戏规则, the rules of the game.

Finally, the decision to use traditional characters was purely an aesthetic decision at that huge font size. Even in mainland China, artists, publishers and others continue to use traditional characters for aesthetic reasons, including in the masthead of Communist Party newspapers. I suspect most print readers of The New York Times who read Chinese are familiar with traditional characters. In any case, the entire series is online in both simplified and traditional characters.

Philip Taylor said,

December 4, 2018 @ 10:43 am

Carl — "I find the use of traditional characters baffling. […] Seems like a case of sheer illiteracy". Not at all clear to me why the use of traditional characters might imply illiteracy. I far prefer the traditional characters to the modern simplified ones, and it seems to me not impossible that the New York Times has similar views …

Neil Kubler said,

December 4, 2018 @ 11:30 am

I agree with Philip Pan's comment that "even in mainland China, artists, publishers and others continue to use traditional characters for aesthetic reasons." For example, traditional characters are often used as the titles of pieces of writing (with the body of the text in simplified); in the names of restaurants, hotels, buildings; on name cards; as brand names of commercial products; inscriptions on paintings and embroidery; funerary inscriptions; and some personal blogs and texts. So what is really happening is that there is something called THE CHINESE WRITING SYSTEM, which includes simplified and traditional (and also the 26 letters of the alphabet, Arabic numerals, punctuation and more), and depending on the formality (register) of the situation, the writer chooses components from that writing system to fit her or his needs at a particular point in time.

Philip Taylor said,

December 4, 2018 @ 3:00 pm

Peter Berresford Ellis' list [1] of European languages that have been 'revived' (he uses the term 'restored' rather than 'revived') — Finnish, Norwegian, Estonian, Latvian, Slovenian, Romanian, Albanian, Faroish, Lithuanian, Armenian and Korean.

——–

[1] Peter Berresford Ellis The Story of the Cornish Language, Tor Mark Press, Truro. Undated first edition, probably circa 1964.

Jerry Packard said,

December 4, 2018 @ 9:24 pm

Well said, Neil.

cliff arroyo said,

December 5, 2018 @ 1:29 am

@Phillip Taylor

Looking at the list,

1) I'm sure Koreans will be surprised to find out they speak a European language

2) None of those languages ever stopped being learned by children AFAIK

3) It looks more like what he's talking about is the creation of standard and/or written languages and maybe some language reforms

4) I think this exchange was probably intended for the thread on Taiwanese

Ricardo said,

December 5, 2018 @ 6:02 am

@cliff arroya

Yes, my initial post was intended for the thread on Taiwanese. But Peter Berresford Ellis‘ list does raise a lot of questions.

@Phillip Taylor

To my mind, a revived language is one that goes from being widely spoken to not being widely spoken to being widely spoken again. (Please don't write asking what do I mean by 'widely'. It's hard to put a precise number of such things and so common sense will have to dictate.) I wonder how many languages on Ellis' satisfy this criteria.

Sean M said,

December 5, 2018 @ 6:39 am

Similarly, I am amazed at how many people want a Latin tag for their coat of arms/fantasy novel/cult initiation and create it with an English-Latin dictionary or Google Translate rather than paying some underemployed classicist (or their daughter in high-school Latin) a 50.

But yes, even in its current less prosperous form you would expect that the NYT would run that past a proofreader fluent in Mandarin!

Victor Mair said,

December 5, 2018 @ 8:53 am

@Philip Pan

Thanks for the detailed, informed explanation.

Victor Mair said,

December 6, 2018 @ 8:50 pm

From Geoff Wade:

When Chris Uhlmann and friends were doing their "China Power" https://www.abc.net.au/news/story-streams/china-power/ series for ABC and Fairfax and were establishing websites etc, I suggested to them quietly that the existing Chinese translation Zhōngguó diànlì 中国电力 ("China [Electric] Power") was probably not the best one available for their intent.

Philip Anderson said,

December 7, 2018 @ 8:51 am

I agree that Ellis was identifying languages that have advanced from being (well-rooted) community languages to being official, if not national, languages.

I would keep “revived” for languages that had dropped out of everyday use, like Hebrew, Cornish, Manx, and perhaps “revitalised” for threatened languages like Breton that are undergoin a revival (see the Diwan schools). But I think only Hebrew is really flourishing.