Spectral Sinographs

« previous post | next post »

Be careful what you write. via the National Diet Library

What brought that about?

It comes from this: "A Spectre is Haunting Unicode", Dampkraft (7/29/18).

The post begins:

In 1978 Japan's Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry established the encoding that would later be known as JIS X 0208, which still serves as an important reference for all Japanese encodings. However, after the JIS standard was released people noticed something strange – several of the added characters had no obvious sources, and nobody could tell what they meant or how they should be pronounced. Nobody was sure where they came from. These are what came to be known as the ghost characters (幽霊文字*).

For a long time the ghost characters remained an unexplained and mostly forgotten curiosity, but in 1997 an investigation was launched to discover where they had come from. While all characters in the JIS standard were supposed to have a record of their sources, even when it existed it wasn't very specific, typically just listing the document it was sourced from.

*yūreimoji

The author, Paul McCann, details the tedious search for the origins of these faux characters and lists the core group:

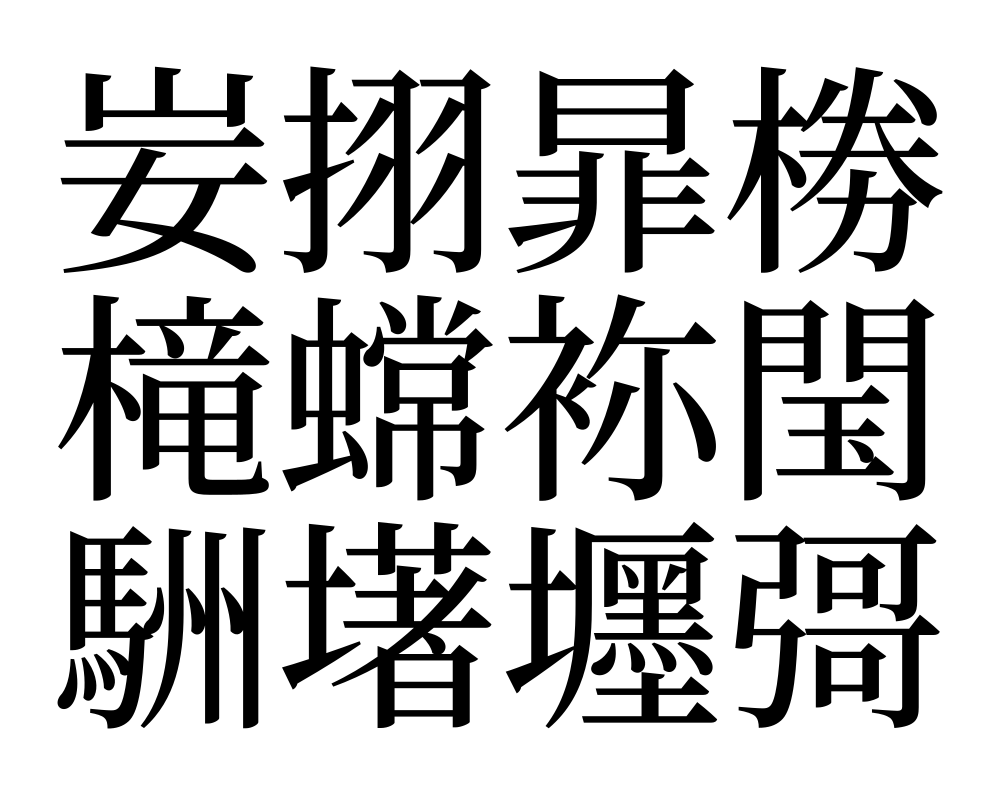

The core ghost characters: 妛挧暃椦槞蟐袮閠駲墸壥彁

I'm particularly taken by that last character, 彁, because it probably is the result of a misreading / miswriting of jiāng 疆 ("border; boundary; frontier"). Of all the tens of thousands of Chinese characters, this is probably the one that I detest most of all. Although it only (!) has 19 strokes (the average character has about 12 strokes, while some characters have as many as 64 strokes — e.g., zhé, four dragons [lóng 龍] jammed together into the same size square as all other characters and appropriately meaning "verbose"), jiāng 疆 ("border; boundary; frontier") is difficult to write with the correct proportions and sequence / number of strokes.

While I was doing archeological work in Xīnjiāng 新疆 (1991-2012), I had to write this character thousands of times on envelopes, in letters, reports, notes, memoranda, etc. — and each time I bemoaned its difficulty. Even though I'm not a fan of simplified characters, whenever I had to write jiāng 疆 ("border; boundary; frontier"), I complained about the fact that the Chinese government didn't provide a simplified form of this refractory Sinograph. After all, Xīnjiāng 新疆 is the name of the Uyghur Autonomous Region which is so much in the news these years. Not only does it occupy one-sixth of the whole of the PRC at a strategic place in the center of Asia, it is also possessed of a wealth of natural resources.

As a matter of fact, I'm not the only one who dislikes having to write jiāng 疆. Many's the time I saw Xīnjiāng 新疆 (lit., "new borders / frontiers / boundaries"), both in private and in public (e.g., on store fronts and signs for other establishments), written as the perfectly homophonous Xīnjiāng 新江 (lit., "new river") — with 13 fewer strokes!

Incidentally, Google Translate is smart enough to recognize that xīnjiāng 新江 means Xinjiang.

I wouldn't be surprised if some bitter person with more initiative than me took it upon himself to create the simplified form 彁 for 疆. Hats off to whomever that might have been! And since we already have 彁 in Unicode with no other sound or meaning attached to it, I hereby propose to the language authorities in China to add it to their list of sanctioned simplified characters.

McCann concludes:

Following the general adoption of the JIS standards these characters all made their way into Unicode, which has its own separate set of ghost characters introduced during CJK unification.

To sum up – in 1978 a series of small mistakes created some characters out of nothing. The errors went undiscovered just long enough to be set in stone, and now these ghosts are, at least in potential, a part of every computer on the planet, lurking in the dark corners of character tables.

At this rate they'll presumably be with humanity forever.

We've talked about Sinographic monstrosities often enough on Language Log. Here are just a few posts:

- "The unpredictability of Chinese character formation and pronunciation" (2/6/12)

- "Writing Chinese characters as a form of punishment" (11/1/15)

- "How many more Chinese characters are needed?" (10/25/16)

- "Mystical Taoist Sinographs" (5/2/18)

- "Really weird sinographs" (5/10/18)

[h.t. Bruce Balden]

Michele said,

July 30, 2018 @ 6:01 pm

So this Ministry just made up these characters out of whole cloth? How weird! Was it a prank, do you think?

Jim Breen said,

July 30, 2018 @ 7:00 pm

I spent part of 2000-2001 as a visiting professor at 東京外国語大学 at the invitation of Kōji Shibano and Masayuki Toyoshima. Shibano was the chair of the JSC committee which looked after the JIS character standards and Toyoshima was a member too, so I had an opportunity to discuss many kanji matters including the source of those doubtful characters. The JSC committee had recently revisited the sources of the 1978 compilation and had identified the sources of many of the odd character versions. These are documented in appendices to the 1997 revision of JIS X 0208. Paul McCann's article fairly accurately describes the review.

The 彁 case was one we discussed, and as I recall it the common view was that the source was the 哥 kanji with a later hand-written squiggle to the left of it that was misinterpreted as a 弓 radical.

Jim Breen said,

July 30, 2018 @ 7:28 pm

Sorry. I meant to write "JSA committee". (日本規格協会).

krogerfoot said,

July 30, 2018 @ 7:39 pm

The nonsense characters could have been concocted for use by Western tattoo artists/aficionados, in hopes of reducing the possibility that college sophomores and aspiring rappers would spend $350 to have "requires refrigeration" inked on their body, thinking it's their initials. I have no evidence for this claim.

Ricardo said,

July 30, 2018 @ 8:46 pm

@krogerfoot

bankers, lawyers, school teachers, prime ministers of Canada and many other types also get tattoos.

John said,

July 30, 2018 @ 11:54 pm

For 疆, since 薑 was simplified into the preexisting 姜, and all were pronounced the same in Middle Chinese, wouldn't 姜 make more sense than 江, pronounced differently in Middle Chinese, Cantonese, etc.?

Lai Ka Yau said,

July 31, 2018 @ 12:31 am

Some of these make sense in Chinese though, which would explain their appearance. 禰 is the surname of 禰衡, a famous character from the Three Kingdoms period thanks to the Romance of the Three Kingdoms. 閠 is another way of writing 閏, which is used in leap years. 櫳 also felt familiar to me and, looking it up, it seems to mean 'window' or 'cage'.

SO said,

July 31, 2018 @ 4:14 am

<< 禰 is the surname of 禰衡

The problematic character is however 袮 with 衤on the left,

not 祢 with 礻. The latter character is not too uncommon in Japan (at least as far as names are concerned); incidentally it is also the basis for both of the modern /ne/ kana: ね and ネ.

J.W. Brewer said,

July 31, 2018 @ 9:47 am

We don't think any of these fake kanji were put there deliberately as bait to catch plagiarists, as is sometimes done by publishers of Western reference works, including dictionaries? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fictitious_entry

krogerfoot said,

July 31, 2018 @ 10:26 am

@Ricardo, tattoos are certainly popular, no argument there. Sinographs make up an extremely popular genre of body ink, overwhelmingly done by and to people who have no knowledge of Chinese or Japanese, to the amusement of people who do.

Ricardo said,

July 31, 2018 @ 8:36 pm

@krogerfoot

Fair enough. I just didn't think that aspiring rappers and college sophomores needed to be singled out, especially since Japanese and Chinese rappers and sophomores also exist and are unlikely to get their sinographs wrong.

Andreas Johansson said,

August 1, 2018 @ 12:08 am

@Ricardo:

I don't know, googling for "misspelled tattoos" turns out quite a few examples of what seems to be Americans with misspelled English in their tattoos. Are Chinese and Japanese all that much more literate?

Ricardo said,

August 1, 2018 @ 12:42 am

@Andreas Johansson

Please read my comments again.

I was not asking or speaking about Americans in general. I was wondering why college sophomores and aspiring rappers were being especially mocked. I do not think that, out of the general population who like tattoos, they are more likely to get their sinographs wrong. And if they happen to be Japenese or Chinese rappers/college students then they are less likely to to get them wrong.

tangent said,

August 1, 2018 @ 4:33 am

They're dords.

krogerfoot said,

August 1, 2018 @ 8:44 pm

Ricardo, my comment was meant to be a joke and wasn't meant to offend college sophomores or aspiring rappers. For what it's worth, in Japan at least you don't see many kanji tattoos, except on Westerners.

Ricardo said,

August 2, 2018 @ 6:05 am

@krogerfoot

I don't deny that it was a harmless joke, though there was a superciliousness to it ('this group of people are not as smart as me and my friends') that was in turn fun to mock.

Ricardo said,

August 2, 2018 @ 6:16 am

After all, having a tattoo that one cannot read is probably not much worse than having some caligraphy in a script that one cannot decipher mounted for display in one's home.

Guy_H said,

August 2, 2018 @ 9:32 am

The 疆 character has a lot of strokes, but I personally don't find it difficult. Its individual components are quite easy to write/type (弓土一田一田一), it has an obvious stroke order and it's not hard to write in proportion. In contrast, 龜 (gui1, turtle) is easily my most hated character – it is a cool looking character but it seems to defy all principles of Chinese writing! My runner-up would be 鬱 (yu4, melancholy) – too many strokes and it looks aesthetically unbalanced (the simplified/variant character 郁 is a vast improvement).

krogerfoot said,

August 2, 2018 @ 11:55 pm

Ricardo, OK then. Your mockery of me (and my friends?) was harmless as well. I don't have any calligraphy on display in my home, but you've got me dead to rights: I guess I do esteem it more than incorrectly written kanji tattoos. I'm afraid rather a lot of people here in Japan probably feel that way.

Ricardo said,

August 3, 2018 @ 7:38 am

I said the superciliousness was fun to mock. No ad hominem from me.