Writing Chinese characters as a form of punishment

« previous post | next post »

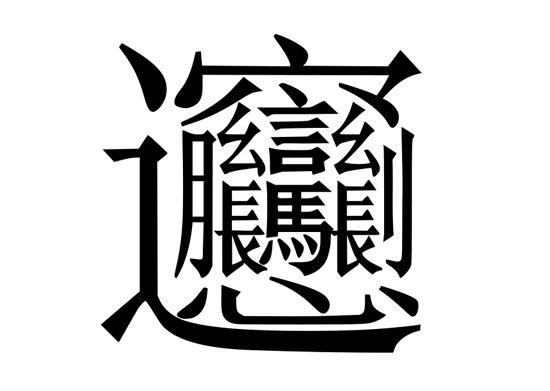

There has been a flurry of reports about a teacher in Sichuan province forcing tardy students to copy a crazy character with 56 strokes a thousand times, e.g.:

"Complex 'character test' facing tardy Chinese students" (10/29/15)

This is the whimsical, whacky character for a type of noodles that is popular in Shaanxi province.

Never mind that some people say the character has 57 strokes, while others say that it has 62 strokes, this zany monstrosity is a bear to write. Having to copy it a thousand times would indeed be a kind of mindless, mind-numbing torture. Furthermore, the sound that has been assigned to it — biang — is not part of the phonological inventory of Modern Standard Mandarin (MSM) and the ostensible phonetic component of this symbol did not develop naturally as part of the sound system of traditional Chinese characters.

Though the BBC article is intended to be humorous, I cannot help but point out one sentence that has two major errors:

Chinese characters are often rated among the most difficult languages in the world to write and master.

Chinese characters are NOT a language, and they certainly are not languages. Taken all together, they constitute a script or writing system.

The author of the article makes better sense when they write:

Experts often say that the only effective way to master the art of writing Chinese is by repetition.

So students frequently practise handwriting exercises, writing out multiple lines of Chinese characters by hand.

This does convey an important truth about the neuromuscular necessity of repeatedly copying the characters if one wishes to be able to write them by hand.

"Character Amnesia" (7/22/10)

Also see this comment, the fourth paragraph from the end of my reply to "flow".

Of course, nowadays, especially with the development of reasonably effective pinyin input systems, most people are "writing" characters by typing them on computers or cell phones, so they no longer have to laboriously trace the strokes of characters, even one that has 56 / 57 / 62 strokes. Their electronic devices do that for them.

"Chinese character inputting" (10/17/15)

The fact that I have had a big copy of this fanciful character for biang prominently posted on my office door for more than a decade attests to my recognition of it as an extreme emblem of certain essential sociocultural features of the Chinese writing system.

QUIZ for character aficionados: do you have an explanation for the inclusion of the various elements that have been brought together to form this character? I'll get you started by pointing out that the two cháng / zhǎng 長 flanking the mǎ 馬 ("horse") are there to emphasize how long the biangbiang noodles are.

[Thanks to C. Lee and S. Smith]

GH said,

November 1, 2015 @ 11:16 am

What? To say that something is "among the most difficult languages" does not imply that it is more than one language.

Victor Mair said,

November 1, 2015 @ 11:18 am

@GH

Think about the plural verb. You used a singular verb in your sentence.

FM said,

November 1, 2015 @ 11:25 am

I think GH is correct — "Chinese characters" is being treated as a grammatically plural, but semantically singular term. Saying "strawberries are among my favorite foods" doesn't mean that each strawberry is separately one of my favorite foods.

Carl said,

November 1, 2015 @ 11:27 am

I respectfully disagree. I think that linguistics needs a better theory of "parasitic" languages. There are a lot of languages/dialects that have a strong relationship to a host language, and I don't think we have a good way of describing those relationships.

As we all know, written languages are never perfect mirrors of spoken languages. For example, comma usage in contemporary standard written English is based on orthographic rules rather than marking pauses for breath. On top of that, things like paragraphs and bullet points have no clear analogue in spoken English. Still, one can't deny that written English, although like a language in its own right in certain respects, is largely parasitic on spoken English.

ASL is an intermediate case. It is more independent of spoken English than written English, but it does use written English for the spellings of words, which in turn is based on spoken English. ASL is an independent language, but it borrows a lot from spoken English.

Literary Chinese, it's fair to say, was an independent language from the spoken dialects of Chinese for most of its history, although still strongly influenced by speech. Today's written Chinese is based on MSM and less independent than literary Chinese was, but like all written languages, it is aloof to a certain degree, and indeed it is probably more independent of MSM than written English is of standard spoken English.

JS said,

November 1, 2015 @ 11:28 am

The claim that "Chinese characters are often rated among the most difficult languages" suggests the author believes that Chinese characters are either a single language or multiple languages, hence the post points out that neither is true.

JS said,

November 1, 2015 @ 11:31 am

And Chinese characters ≠ literary Chinese.

Matt Anderson said,

November 1, 2015 @ 11:43 am

It never occurred to me that there was any logic to the construction of this character, which I think was just made up to sell noodles, so I never looked for any. But I guess there is a reason after all that these particular components were selected.

So I'll try my hand at the quiz. Is [幺言幺] supposed to be a variant of luán 䜌 (that's [糸言糸] if it doesn't display correctly), serving as the phonetic component? And I guess ròu 月 'meat' and dāo 刂 'knife' are there to suggest 'cut meat'. Maybe chuò 辶 'walk, run' and mǎ 馬 'horse' are there to suggest that people would travel to eat these noodles? I don't really have any idea about xué 穴 'cave' and xīn 心 'heart', though. The bowl is like a cave? The heart is there because it makes the eater feel good?

Joseph said,

November 1, 2015 @ 12:18 pm

I understand that copying Chinese characters had a long history as a form of punishment in East Asia, something I was told that I thought of when I read this post was that it was the lower ranking monks who were made to copy Buddhist sutras in Nara Japan. We can know too that they didn't enjoy it.

My attempt to explain the components for the character biang- the 宀 is of course the roof of the noodle restaurant, the two lines under that 八 is an open mouth eating noodles, the 言 and the two 幺幺 represent the character wan 彎 for the bending of the noodle, but maybe also the character bian 變 as a phonetic or as an inside joke for the strangeness and exaggerated character for the noodle. Professor Mair already explained the two 長 as representing the length of the noodle, and I've heard before that long noodles represent long life for the Chinese so this makes sense. The horse 馬, meat 月, and knife刂radicals mean cutting horse meat to put in with the noodles, for of course Chinese eat all kinds of animals. The mind radical 心 means that this noodle eating or horse cutting has not taken place yet, but that one is thinking about the act of eating the noodles or noodle preparation. The 辶 radical means going for a walk after eating the the long noodles for a long life, Chinese often say "if walking a hundred paces after a meal, one will live to 99 years of age." 飯後百步走,活到九十九

J. W. Brewer said,

November 1, 2015 @ 5:52 pm

The food at http://www.biang-nyc.com/ is pretty good, and they offer a menu suitable for those who can neither speak any Sinitic language nor read the characters.

shubert said,

November 1, 2015 @ 9:46 pm

http://www.china.com.cn/book/txt/2009-10/28/content_18784940.htm

you can read roughly by Google translation

Jeff W said,

November 2, 2015 @ 12:12 am

@ Victor Mair

And your students are great at getting to class on time, I bet.

Victor Mair said,

November 2, 2015 @ 7:40 am

@Jeff W

Yep! Even for one that begins at 9 a.m. (for the most part).

Victor Mair said,

November 2, 2015 @ 7:41 am

Notice that, in the version of the character presented in the article at the link provided by shubert, the sī 絲 ("thread; silk"; duplication of Kangxi radical 120) flanking the yán 言 ("speech"; Kangxi radical 149), which is unsimplified, has been simplified to 丝, the two 長 ("long"; Kangxi radical 168) flanking the "horse" (simplified from 馬 [Kangxi radical 187] to 马) have been simplified to 长, while the dāo 刂("knife"; Kangxi radical 18) has been replaced by gē 戈 ("halberd; spear"; Kangxi radical 62). Kinda defeats the purpose of trying to squeeze as many strokes into as small a space as possible.

MrFnortner said,

November 2, 2015 @ 7:48 am

Skill-building as punishment was popular in my 1950s grade school, often handed out by Patrol Boys for school yard infractions. A popular type was excruciatingly long math problems such as "squaring a number." Typically a three-digit number was assigned and the guilty party would square it and subtract it from its square repeatedly until reaching zero. All pages of the arithmetic exercise were to be handed in, and the final answer had to be zero, exactly. I learned to love math, natural patterns, and cheating via this punishment.

shubert said,

November 2, 2015 @ 10:44 am

Nocturnal emission sperm was called "galloping horse" ; the upper part 穴 cave is part of vagina.

Leo E said,

November 2, 2015 @ 11:21 am

I wonder if students in Japan are ever punished with having to write this:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taito_(kanji)

J. W. Brewer said,

November 2, 2015 @ 4:00 pm

Repetitive writing as punishment is sufficiently common at least on a hearsay/folklore basis in U.S. primary education as to be the basis for parody: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Simpsons_opening_sequence#Chalkboard_gag. Although typically the things written is not that they are unusually orthographically challenging.

David Fried said,

November 2, 2015 @ 9:15 pm

A question from someone who is wholly ignorant of Chinese: Isn't the whole thing an amusing semi-abstract picture of a plate or bowl of noodles? Aren't the elements really selected to make such a picture, rather than for their meaning? And if the name of the dish is the character reduplicated–well a very long noodle deserves a very long written name.

Apart from that, the character seems more or less the "antidisestablishmentarianism" or "supercalifragilisticexpialadocious" of Chinese, or perhaps the Llanfairpwyll. . .

Jeff W said,

November 3, 2015 @ 4:23 am

Ha, whatever works.

⁂ ⁂ ⁂

Linguist Arika Okrent says “There are different theories about how the character [biáng] came to be, but the most plausible one is that the owner of a noodle shop made it up.” (Wikipedia says that also.) So maybe it is a bit of a publicity stunt, like Llanfairpwll, mentioned by David Fried.

Is that why the character is “whimsical”—because someone just dreamed it up?