In English-language conversations, older people tend to use UH more often and UM less often. And at every age, men tend to use UH more than women, and women tend to use UM more than men. These effects are large and robust – they've been documented in at least five independent datasets, from both North American and Great Britain — for details, see the links at the end of this post.

The cited patterns are consistent with two quite different classes of explanation:

- There might be a language change in progress, with older people reflecting the patterns of an earlier time and younger people showing the language of the future, while women are leading the change, as they often do.

- There might be stable gender and life-cycle effects, so that the UM and UH sex and age associations looked the same a few decades in the past, and will look the same a few decades in the future.

And there's an independent question about the functions of the classes of vocalizations that we transcribe as UM and UH:

- Perhaps UM and UH are simply alternative expressions of the same compositional or communicative function — say, two different (classes of) ways of stalling for time in the process of speaking — or alternatively

- perhaps UM and UH have partly or entirely different functions, and it's differences in the frequency of these functions that are associated with age, sex, and so on.

In neither case are the alternatives mutually exclusive — the truth might be some mixture of the two.

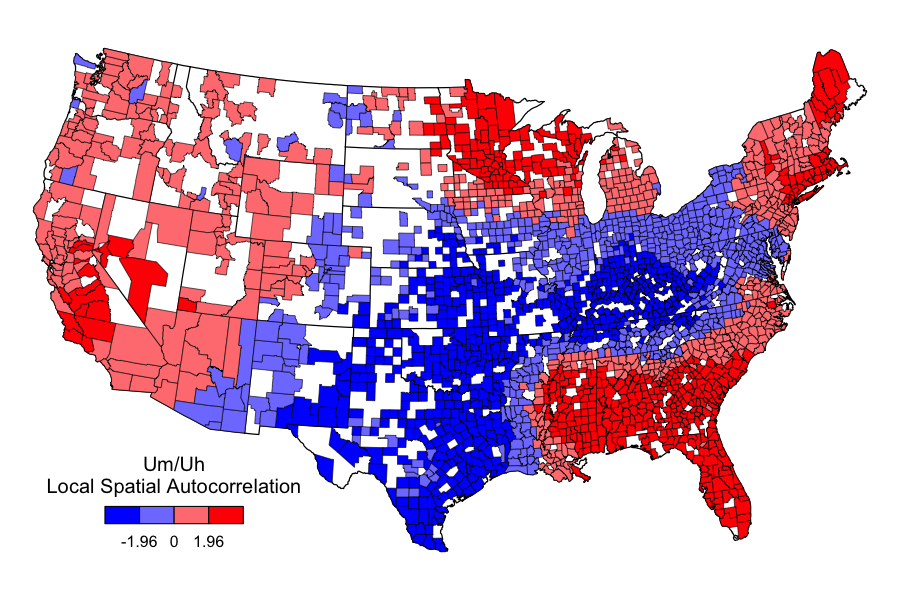

Yesterday, Joe Fruehwald looked at UM and UH usage in a dataset with enough time depth that we can tell the difference between a change in progress and a stable life-cycle effect. And he found that the truth seems to be a bit of both.

Read the rest of this entry »