Uptalk anxiety

« previous post | next post »

A few days ago, I received this poignant note from an anxious parent in Pittsburgh:

I have developed a serious interest in the origination of uptalking and methods to treat it. As absurd as it may sound, my daughter is a Ph.D. and lives in another city. When she visits me, she populates most of her explanations with uptalking. She is a psychologist.

When I am conversing with her I become extremely anxious since I have fixated on the uptalking and it puts me at a severe level of discomfort. I discussed it with her several times. She claims that it is a speech pattern she developed which is normal and that it is my problem. I noticed that many of her friends, all professionals including psychologists, attorneys and physicians also engage in uptalking. Though she vehemently denies that she can stop uptalking to me, when she is angry she speaks perfectly. It appears that it is a psychological insecurity requesting some sort of approval or affirmation from the listener that what the talker says is correct, approved by the listener or adequately explained to the listener.

My daughter recommended that I seek therapy and that it is my problem. Has any research been done to show that not only has the phenomenon of uptalking been documented and described, but that it can have very negative affects on the listener?

Dear Anxious,

You're certainly entitled to your crotchets and irks, just as your adult daughter is entitled to her prosodic preferences. But in order for the two of you to get along, something's going to have to give. And realistically, it's you — children generally speak like their peers, not like their parents. Luckily, experience shows that cognitive therapy can be very effective in such cases.

As a first step, you should get your peeve on, primal scream style, by listening to Taylor Mali reciting his poem "Totally like whatever":

In case you hadn't realized

it has somehow become uncool

to sound like you know what you're talking about?

Share his outrage. Then ask your daughter to listen with you, to help her understand the nature and strength of your reactions. As you listen, though, consider this: do Mali's phrase-final rises really indicate "psychological insecurity requesting some sort of approval or affirmation from the listener"?

Or is he compelling the audience to confront his (mock) anger?

When I wrote about this a few years ago, I invited readers to imagine me poking my finger at him and explaining, rising on every phrase, that

That is, like, such total crap?

You've got no idea whatever

about how people actually, like,

communicate, you know?

In her 1991 dissertation, Cynthia McLemore suggested that final rises iconically signal some kind of connection. This might be a connection between ideas, as in non-terminal list items; or it might be a connection between speaker and hearer, as in a question and the answer or a statement and the listeners' attention. But she pointed out that this kind of reaching out to listeners need not be a sign of insecurity or even politeness. And in her data, taken from a careful study of the role of intonation in a University of Texas sorority, final rises were associated with statements by more senior and more powerful members that required audience attention and action.

Winnie Cheng and Martin Warren found something similar in a 2005 corpus study of English in Hong Kong. In four business meetings, two chaired by women and two by men, the chairs used rising tones almost three times more often than the other participants did (329 times vs. 112 times). In conversations between academic supervisors and their supervisees, the supervisors used rising tones almost seven times more often than the supervisees (765 times vs. 117 times). Cheng and Warren cite David Brazil's idea that what he called "rise tones" can be used to "assert dominance and control" by holding the floor, by exerting pressure on the hearer to respond, or by reminding the hearer(s) of common ground.

But Taylor Mali's poetic screed simultaneously illustrates and subverts a deeply embedded stereotype that final rises are young, insecure, and feminine. Thus Kate Zernike, "Postfeminism and Other Fairy Tales", NYT 3/16/2008 NYT 3/16/2008, quotes from Katha Pollitt's essay in the book Thirty Ways of Looking at Hillary:

[T]he hysterical insults flung at Hillary Clinton are just a franker, crazier version of the everyday insults — shrill, strident, angry, ranting, unattractive — that are flung at any vaguely liberal mildly feminist woman who shows a bit of spirit and independence, who puts herself out in the public realm, who doesn’t fumble and look up coyly from underneath her hair and give her declarative sentences the cadence of a question.

This view of final rises was popularized among feminists by Robin Lakoff's 1975 monograph Language and Women's Place, where she wrote

There is a peculiar sentence intonation pattern, found in English as far as I know only among women, which has the form of a declarative answer to a question, and is used as such, but has the rising inflection typical of a yes-no question… The effect is as though one were seeking confirmation, though at the same time the speaker may be the only one who has the requisite information.

But in fact, final rises are often used by males attempting to assert dominance, as exemplified by Taylor Mali's poem, and documented by Cheng and Warren, and discussed in earlier Language Log posts here

(where the uptalker is a very angry former NASA official) and here

(where the uptalker is President George W. Bush).

The association of uptalk with insecure women seems exemplify the complex of selective attention and confirmation bias that Arnold Zwicky has called the "out-group illusion": "… people pay attention selectively to members of groups they don't see themselves as belonging to and so locate phenomena as characteristics of these groups." (See my post "The social psychology of linguistic naming and shaming" for some further discussion.)

On the other hand, there's evidence — from sources other than your daughter — that the relative frequency of final rises (and thus their effective meaning) has changed over the past few decades, among younger speakers of both sexes in many parts of the English-speaking world.

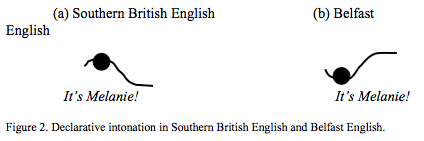

And in interpreting this historical change, it's also important to note that regional varieties of English have long-established differences in the relative frequency — and also in the conventional interpretation — of various phrasal melodies. Thus Esther Grabe, Greg Kochanski and John Coleman, "The Intonation of Native Accent Varieties in the British Isles: Potential for Miscommunication?" (from Katarzyna Dziubalska-Kolaczyk and Joanna Przedlacka (eds.), English pronunciation models: a changing scene, 2005) reproduces this "tadpole diagram" of the traditional distinction between the intonation of emphatic statements in the south of English and in Ulster:

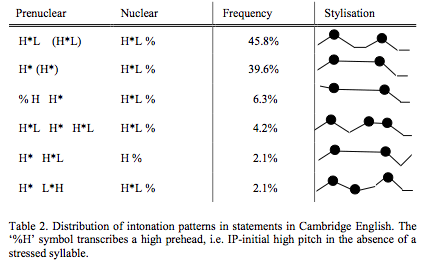

They categorized and counted intonation patterns in the IViE ("Intonational Variation in English") corpus, and their counts confirm this traditional account in a more detailed form. In Cambridge English, final rises occurred very rarely on statements:

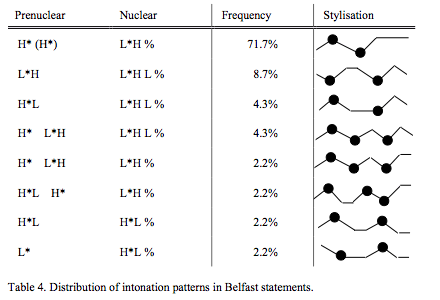

In contrast, in Belfast, more than 95% of statements had a rising pattern on the last stressed syllable, and most ended with a phrase-final high as well:

Does this reflect a greater prevalence among Belfast natives of insecurity, need for confirmation, or desire to assert dominance and control? Surely not — it's just a regional difference in intonational patterns, just as there is regional variation in vowel quality.

Daniel Hirst has recently suggested a historical explanation for the prevalence of rising intonations on statements in the north of Britain:

A number of North British accents (Glasgow, Belfast, Liverpool, Birmingham, Tyneside) (Cruttenden 1986) … systematically use rising pitch at the end of what are clearly statements. In one of the first descriptions of the [these] rising patterns, Knowles (1975) suggested that the pattern could be of Celtic origin since the speakers of the Liverpool dialect which he studied (Scouse) were mostly of Irish origin. Cruttenden (1995) questioned this hypothesis, since while it would account for most of the UNB cities it would not account for Tyneside (Pellow & Jones 1977). Cruttenden cites evidence that the Irish population there was almost inexistant before 1830 and that the Scots there were mainly from the Eastern lowland regions where the pattern is not observed, whereas there is documentary evidence that the "Tyneside Tone" was well established before the nineteenth century. The hypothesis also fails to explain why the pattern is found in only some parts of the Celtic speaking areas of Britain but not in others (Southern Ireland, Wales, Western Scotland). There does not seem to be any historical distribution to explain this distribution.

I have observed (Hirst 1998) that the original distribution of these populations (before the shift from Western Scotland to Northern Ireland then to West Midland England) did have something in common: both Tyneside and Western Scotland were areas of intense raiding and settlement by Norwegian Vikings in the early 9th century. Recent genetic evidence (Oppenheimer 2006) suggests in fact that strong connections between these populations largely antedates the Viking raids.

The fact that West Norwegian intonation has also been described as having rising terminal tunes in statements (Fretheim & Nilsen 1989) makes the hypothesis of a Nordic Prosody origin for these intonation patterns even more attractive.

Let's note in passing that 9th-century Viking warriors were not stereotypically insecure or in need of approval or affirmation from their interlocutors.

Whether or not Daniel's hypothesis is correct, the recent world-wide rise in "uptalk" can't be blamed on the Vikings, at least not directly. But perhaps this historical perspective will help you to make linguistic peace with your uptalking daughter and her professional friends. Think of them as urban Vikings, striking out from home and hearth to conquer new cities with their ascending assertions.

Marinus said,

September 7, 2008 @ 7:58 am

For what it's worth, rising tones at the end of sentences is a standard feature of the New Zealand accent as well, and one that many migrants like myself and my family have picked up very quickly.

Marinus said,

September 7, 2008 @ 8:02 am

As the grammatical error might have shown, English isn't my first language. Nonetheless, those distinctive rising tones have even seeped into how I speak my first language, on the rare occasions where I still do, wherein we normally have descending final intonations like most everyone else.

Sili said,

September 7, 2008 @ 8:23 am

Well … they coulda been overcompensating for their innate insecurities.

[links] Link salad for a Sunday | jlake.com said,

September 7, 2008 @ 8:44 am

[…] Uptalk anxiety — Language Log goes pretty deep into linguistic geek funnies on this one. For example, in ascribing certain regional British speech features to Viking populations, "Let's note in passing that 9th-century Viking warriors were not stereotypically insecure or in need of approval or affirmation from their interlocutors." […]

Trent said,

September 7, 2008 @ 8:49 am

Excellent post.

I was aware of this phenomena, but unaware of the term "uptalking." At first I thought Mark was going to defend its usage. …

Usually uptalking doesn't bother me, but occasionally I'm annoyed because if I'm listening very carefully I dislike the tiny break in concentration it takes to nod assent, which sometimes seems to be required. In other words, I'm required to immediately assent to each point as presented. By the end of the speaker's utterances, I've already granted each premise and presumably am locked into the conclusion. Of course, it doesn't really work that way, but that is how it feels. An alternative is to treat the nods as acknowledgment without assent.

What I've found (and this is just personal observation; I've done no research on this) is that if you bend your ear toward the speaker, you can indicate complete concentration (which reassures the speaker) without having to affirm every phrase uttered.

James Wimberley said,

September 7, 2008 @ 9:07 am

Tadpole or spermatozoon?

rootlesscosmo said,

September 7, 2008 @ 10:33 am

Without getting into possible explanations for the origins or increased use of uptalking, I'd suggest that irritation with uptalking derives in part from the way it serves as a generational marker; your worried correspondent, for example, hears in every uptalking sentence of his daughter a reminder that he is old, and not only old but old-fashioned. As I can testify–it may be relevant to mention that I'm 66–this is disagreeable.

John Cowan said,

September 7, 2008 @ 11:24 am

By "bend your ear" you mean with your fingers?

Brett said,

September 7, 2008 @ 12:19 pm

I know I use uptalk to convey information about the role my statements are supposed to play. In particular, when talking to my graduate students, I tend to use uptalk when we're sitting down discussing a calculation. This is by no means conscious, but it expresses the implicit sentiment that when I explain something in this context, I want some kind of acknowledgment that the students grasps what I'm trying to say. Or rather, I would like a student to stop me if he or she doesn't understand. However, if the discussions get particularly difficult, and I have to move to the blackboard to explain something, the uptalk goes away. It becomes more like a lecture, where I don't expect instant feedback.

I'd also like to say that I found the use of "tadpole diagram" very odd in this context, since it's also a term used in physics (where it appears to be older and also much more common than in linguistics), and purely geometrically speaking, the diagrams shown do not match the criteria I'm used to recognizing as signifying a "tadpole."

Mark Liberman said,

September 7, 2008 @ 12:39 pm

Brett: I'd also like to say that I found the use of "tadpole diagram" very odd in this context, since it's also a term used in physics (where it appears to be older and also much more common than in linguistics), and purely geometrically speaking, the diagrams shown do not match the criteria I'm used to recognizing as signifying a "tadpole."

I'm not sure about the antiquity of the term, but I believe that the use of the diagrams themselves in British intonational descriptions goes back at least to O'Connor & Arnold 1961 (Intonation of Colloquial English), which would make them at least a few years older than the tadpole diagrams that appeared in Coleman and Glashow, Physical Review B v. 134, p.671 (1964).

Yes, I just checked my copy (which is the 1963 printing, but unchanged in this respect from the 1961 edition), and the "tadpole diagrams" are there (though not, as far as I can tell, the term).

GTA said,

September 7, 2008 @ 12:57 pm

Some years ago, I commented to a colleague, a linguist, that another colleague from, I think, County Donegal, was uptalking (I actually said that he was using upspeak, but it's evidently the same thing. The linguist suggested that I was actually hearing level pitch at the ends of sentences, but that because I expected falling pitch, I interpreted level pitch as rising pitch. What do you think?

Bob Ladd said,

September 7, 2008 @ 1:35 pm

It's important not to confuse the rises in Belfast, Glasgow, etc. with uptalk. They're phonetically and functionally very different. I've laid out the reasons in my book Intonational Phonology (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1996; second edition due out shortly), and won't repeat them all here because it would take too much space. But you can listen to a sample from Glasgow here and hear for yourself that it doesn't sound like North American (or Oz/NZ) uptalk. The speaker, for reasons too complicated to into, is saying "and then a diamond mine" and the phrase occurred at the end of a sentence (or, more technically, at the end of a "turn").

I'm pretty sure that tadpole diagrams in the British tradition of intonation description are considerably older than O'Connor and Arnold's 1961 book. Undoubtedly John Wells could give us some idea of how long the term "tadpole diagram" has been in use.

Bob Ladd said,

September 7, 2008 @ 1:38 pm

Sorry, got the link wrong; the sound file of the Glasgow "rise" is here.

Luther von Ruckerson said,

September 7, 2008 @ 1:42 pm

Interestingly, I have developed a serious dislike of "downtalking", particularly when it is used at the end of a question. It sounds snobby and gives me the impression the questioner is trying to dominate the listener. I not only do not like it in English, but my wife, who is from Honduras, uses downtalking in Spanish when talking to our child. I avoid speaking Spanish with her because of it. I think I need a bit of the old cognitive behavioral therapy my self…

I do not seem to be much bothered by uptalking, and find it attractive and compelling in some cases. I'm thinking of NPR's Terry Gross, who uptalks constantly when interviewing.

Bobbie said,

September 7, 2008 @ 2:24 pm

A few years ago uptalk was the rage among young women from Caifornia and became known as "Valley Girl" [talk]. I hear it a lot these days among younger people. For that matter, when was the last time you heard anyone over 40 years old using uptalk?

Mark Liberman said,

September 7, 2008 @ 2:31 pm

Bob Ladd: It's important not to confuse the rises in Belfast, Glasgow, etc. with uptalk. They're phonetically and functionally very different.

There's no question at all that they're *functionally* different.

In terms of sound, though, I think that the issue is less clear. The statistical distribution of the F0 time functions is also no doubt different — and probably different among the various northern locations as well — but I'm fairly sure, at least on the basis of informal but fairly extensive inspection and listening, that individual pitch contours are often ambiguous.

Bob, are you confident that you could tell the difference, on short phrases whose F0 and amplitude contour was used to modulate a non-speech oscillator, in the mode of the example e.g. here?

A similar sort of question can be asked about the kinds of final rises used in the cited speech by George W. Bush. No one interprets this sort of thing as "uptalk", in fact, even when the final rises are pointed out to them. But is that because there is really a difference in the pitch contour? Or is it the difference in context, and other aspects of the delivery, that leads people to interpret it as an instance of a different category? I've spent a certain amount of time trying to find a reliable difference between the cases in terms of F0 patterns, without much success.

Mark Liberman said,

September 7, 2008 @ 2:44 pm

Bobbie: A few years ago uptalk was the rage among young women from Caifornia and became known as "Valley Girl" [talk].

This is often said. Interestingly, if you listen to the original Frank Zappa/Moon Zappa "Valley Girl" single from 1982 (here and here), there's not much that you could call "uptalk" on it. Instead, the main intonational hook is the swooping rise-fall like on the famous "oh my god".

And equally odd is the fact that (as far as I can remember) there wasn't much uptalk in the 1983 movie "Valley Girl" (trailer here).

I'm not saying that young women from the San Fernando Valley in the 1980s and 1990s didn't participate in the general increase in final-rising intonation, or even lead it — I don't know any good evidence about this one way or the other — just that there seems to be a curious lack of uptalk in the cultural artifacts that brought the "Valley Girl" and "Valspeak" concepts into popular discourse.

Bobbie: I hear it a lot these days among younger people. For that matter, when was the last time you heard anyone over 40 years old using uptalk?

Well, if uptalk is defined as long sequences of phrase-final rises on declaratives, then the answer is "all the time". For example, how about the clip from George W. Bush cited in the body of this post? He was 59 at the time that the recording was made.

Roy G. Ovrebo said,

September 7, 2008 @ 2:44 pm

The fact that West Norwegian intonation has also been described as having rising terminal tunes in statements (Fretheim & Nilsen 1989) makes the hypothesis of a Nordic Prosody origin for these intonation patterns even more attractive.

According to this reference list the Fretheim/Nilsen paper is about terminal rise in East Norwegian.

Here in the west, terminal rise is a spoken question mark. To us, it's one of the more mockable features of eastern accents.

Mark Liberman said,

September 7, 2008 @ 2:57 pm

Roy G. Ovrebo: According to this reference list the Fretheim/Nilsen paper is about terminal rise in East Norwegian.

Must be a typo in Daniel Hirst's abstract. I'll ask him.

Andrej Bjelakovic said,

September 7, 2008 @ 3:32 pm

An interesting analogy occurred to me a couple of years ago when a cousin of mine originally brought my attention to the fact that I had started using uptalk.

It has to do with the usual intonation when listing items. If I'm not mistaken it is common in English to have a rising intonation on all items except the last one, which has a fall. E.g. "So, we have coke… sprite… orange juice and… beer."

Now, I may be just rationalizing my speech habits here, but it seems to me that when I'm using uptalk it's to signal that I'm still driving the point home, and the story's not over yet. So each sentence has a rise until I've come to and end, where I make a fall and that's a signal that I'm finished and that it's the other person's turn to speak.\

Does this make any sense, or am I just rambling?

Mark Liberman said,

September 7, 2008 @ 4:24 pm

Andrej Bjelakovic: If I'm not mistaken it is common in English to have a rising intonation on all items except the last one, […]

Now, I may be just rationalizing my speech habits here, but it seems to me that when I'm using uptalk it's to signal that I'm still driving the point home, and the story's not over yet.

This analogy is part of McLemore's point about the role of final rises in connecting interlocutors as well as phrases or ideas; and Brazil's point about rises being used to "hold the floor". Others have built on this general idea in other ways, before and since. So your idea is a sensible one that others have also had.

Bobbie said,

September 7, 2008 @ 5:20 pm

I listened (again) to the clip from George W. Bush and, to me, it sounds like he was making a list of what he recently accomplished, as if he was trying to convince the listeners that he had really done a lot of work. The uptalk made it sound like he wasn't sure that it was significant. It would have sounded more forceful without the uptalk.

Roy G. Ovrebo said,

September 7, 2008 @ 5:39 pm

If I'm not mistaken it is common in English to have a rising intonation on all items except the last one, which has a fall.

One case of this football results – essentially lists of two items each. When read in British media, it'll sound like

Hibernian 1? – Celtic 1., Motherwell 1? – Kilmarnock 2.

dr pepper said,

September 7, 2008 @ 5:57 pm

A local display of birthday cards feature one that shows three teenaged boys dressed in casual California play clothes. Underneath it says "Dude, you're like–" and inside it says "old!". It's not really funny unless you hear the uptalk at the end, and the sort of thickened pronunciation of "dude" at the beginning.

the other Mark P said,

September 7, 2008 @ 6:05 pm

"For that matter, when was the last time you heard anyone over 40 years old using uptalk?"

Every day. Because in New Zealand it is standard (as Marinus also said).

Stuart said,

September 7, 2008 @ 6:23 pm

"When I am conversing with her I become extremely anxious since I have fixated on the uptalking and it puts me at a severe level of discomfort."

I've never commented at Language Log before, but as a 40+ uptalking Kiwi, I was flummoxes by this. How did prescriptivism become so ingrained in so many US English speakers that a simple difference in intonation can cause such distress? Together with articles like Wired's "analysis" of the alleged Steven Jobs emails, and the Washington Post 's ode to Strunk, it leaves me bewildered and bemused.

Is this assumption that there is one right way and a multitude of wrong ways for every element of language part of the way English is taught in the US?

nascardaughter said,

September 7, 2008 @ 9:13 pm

How did prescriptivism become so ingrained in so many US English speakers that a simple difference in intonation can cause such distress?

Different sound patterns can convey different social meanings in different contexts. Maybe in the mother's peer speech communities, this pattern signifies one thing, while in the daughter's, it signifies another. I think that a "simple difference in intonation" could cause quite a lot of people stress, prescriptivism or no prescriptivism, when the meaning intended by the speaker conflicts with the meaning perceived by the hearer.

Eyebrows McGee said,

September 7, 2008 @ 9:35 pm

Oh, man, you're giving me flashbacks — my father used to (metaphorically) smack me down for uptalking at family dinner all through junior high, until I (mostly) quit it.

Now I'm going to spend the whole week listening to how often my students use it.

Stuart said,

September 7, 2008 @ 9:43 pm

Maybe in the mother's peer speech communities, this pattern signifies one thing, while in the daughter's, it signifies another.

That I can understand. I can see that the difference could cause some confusion, but this is a mother speaking of her daughter. She says the difference in intonation makes her "extremely anxious" and causes her "a severe level of discomfort". Perhaps that was intentional hyperbole. If not, I'm at a loss to understand how any confusion caused by the difference in intonation could cause that much of a problem between a mother and her child.

nascardaughter said,

September 7, 2008 @ 10:26 pm

She says the difference in intonation makes her "extremely anxious" and causes her "a severe level of discomfort".

Yeah, the letter writer's reaction does seem kind of extreme, whatever the source of it is.

linda seebach said,

September 8, 2008 @ 2:02 am

Funny, I assumed the distressed parent was a father.

And more generally, my son adopted uptalking when he worked for a telephone survey company for a few months; I thought it was a matter of trying to sound sufficiently deferential that people wouldn't hang up on him (the opposite of demonstrating dominance).

It's mostly worn off, but it took years.

Tom said,

September 8, 2008 @ 8:24 am

Here in the UK what are often called "high rise terminals" are usually blamed on yoof culture from two sources: Australia and America. Particularly the former, thanks to the popularity of soaps like Neighbours and Home & Away, both integral to growing up and being a student throughout the 80s and 90s.

Arnold Zwicky said,

September 8, 2008 @ 11:49 am

Linda Seebach: "Funny, I assumed the distressed parent was a father."

Mark Liberman craftily gave no clue to the sex of the distressed parent, but almost everyone reading the parent's letter seems to have taken the expression of extreme anxiety as feminine. Nice example of stereotyping. I suppose that if the letter-writer had expressed outrage and anger, people would have guessed that the writer was a man.

On a related point: Mark carefully refers to the daughter as the writer's "adult child" (that the daughter is adult is quite clear from the letter), but some references to Mark's posting in other blogs just use "child", thus inviting the interpretation that the daughter was young ("below the age of full physical development or below the legal age of majority", as NOAD2 puts it). That in turn invites a rather different take — "kids these days!" — on the parent-child relationship. (The ambiguity in English between two senses of child — young human being vs. offspring, son or daughter of any age — is frequently troublesome.)

Arnold Zwicky said,

September 8, 2008 @ 12:19 pm

Re Brett and Mark Liberman on the term "tadpole diagram". Mark has been earnestly looking into the history of the term in two very different domains, but I don't have a lot of patience with priority claims for terminology (Brett's idea seems to be that phoneticians shouldn't be using the term because physicists used it first in a different sense, so the phoneticians' use is confusing), especially when the terminology involves a natural metaphor (as in this case) or word-building using Greek or Latin elements in a natural way (as in the case of "morphology", with the morph- 'form' root, used in different senses in biology, linguistics, astronomy, folklore, and geology). Technical terms, like ordinary-language vocabulary, are understood in context, so that there should be no problem with the "same" term used with different meanings in different technical domains. In fact, given the need for an enormous number of technical terms in a great many domains, it would be folly to insist that each term have only one use.

TootsNYC said,

September 8, 2008 @ 3:48 pm

Is it possible that part of why our worried parent is so annoyed by the daughter uptalk is that, a la these comments:

______________

Mark Lieberman: "final rises were associated with statements by more senior and more powerful members that required audience attention and action"

David Brazil's idea, as described by M.L.: the called "rise tones" can be used to "assert dominance and control" by holding the floor, by exerting pressure on the hearer to respond, or by reminding the hearer(s) of common ground.

Trent: " I dislike the tiny break in concentration it takes to nod assent, which sometimes seems to be required. In other words, I'm required to immediately assent to each point as presented. By the end of the speaker's utterances, I've already granted each premise and presumably am locked into the conclusion."

Brett: "I want some kind of acknowledgment"

_________

the parent is feeling a bit manipulated, as if he or she is losing a power struggle with the daughter?

I think that's a fascinating observation–that uptalk can be about power, and demanding attention, acknowledgment, assent.

TootsNYC said,

September 8, 2008 @ 3:53 pm

Is it possible that the rise in uptalk is because the speakers are afraid other people are going to stop listening to them, and tune them out?

Terry Hunt said,

September 8, 2008 @ 4:12 pm

I concur anecdotally with Tom. As a 51-year old Brit who has lived and travelled widely in the UK (as well as with British Army personnel and families in the Far East and Germany), I began to notice widespread declarative uptalking in the UK population only after the mid-1980s advent of 'Neighbours' (and its subsequent Australasian spinoffs/rivals). These shows were, perhaps due to exoticism and scheduling, popular with teenagers, who are not slow to perpetuate a fad if it is seen to annoy adults, and declarative uptalking annoys the hell out of most people over 35 I know.

As Nascardaughter said, the irritation surely arises from the anxiety caused by this intonation pattern meaning different things to the two age groups, To us oldies, it sounds like misconstrued questioning, uncertainty, or insecure approval-seeking even though it is (usually) not, and we have to suppress our own early language conditioning (and rhetorical training, if any) and make a more conscious effort to discern what might be being implied.

I suspect that the counter-examples of certain UK regional accents are a red herring. In such regional variations as we become familiar with, we learn their particular uptalk-like patterns along with all their other relative (to us) peculiarities, and become attuned to them in those specific contexts. We're better at this sort of thing than we generally realise, are we not?

Of course, it's easy enough to avoid declarative-uptalk annoyances simply by shunning everyone under 35, or 40 to be on the safe side ;-), but personal intolerance aside, surely this is a fascinating example of language micro-evolution, which generation-by-generation builds up until we find Dickensian English amusing, Shakespearean English tricky, Chaucerian English problematical, and Proto-Indo-European a conundrum.

Roy G Obrevo is perhaps a little off-target with his football-scores example. In the classic mode of results delivery, probably invented within pre-TV BBC radio to facilitate pools-checking, it's easy to anticipate a home win, draw or away win solely from the intonations given to the home-team name and score. Thus if the Seaport v Newtown result is 1:0, "Sea-port-one . . ." goes (crudely) mid-low-mid; if 1:1, it goes mid-high-high; if 1:2, it goes high-low-mid. The away-team name and score correspondingly have different patterns in each case, polysyllabic names complicate matters, and emphases and rhythms are also involved, quite beyond my ability to reproduce textually. I wonder if a linguistic study of this has ever been done?

Regarding Arnold Zwicky's point above about technical terms validly meaning different things within different disciplines (and in lay life), there is one term relevant to linguistics that appears to cause a good deal of misunderstanding, namely "genetic." When the realms of biology and language overlap in the allied studies of population movements and descent, and language and other cultural evolutions and transmissions, biologists and linguists (or their lay interpreters) seem all too often to confuse their two subtly distinct meanings of this word, and much unnecessary heat ensues. Perhaps we need a potted joint summation of their definitions, for easy reference and refereeing.

Is it just me who keeps reading "Phoenician" for "Phonetician?"

Bloix said,

September 8, 2008 @ 4:48 pm

Uptalk demands assent. It does not admit the possibility that the listener might disagree or have a different point of view. This is precisely how it's used in the Taylor Mali poem. Used between friends, it's a way of signifying solidarity against the outside world – we two understand each other completely – while used with an outsider, it's a form of bullying. It's smug, which is why it upsets the mother so much.

It reminds me a bit of the infuriating English habit of ending declarative statements with "isn't it" or "shouldn't you" or some other question form that demands the response "yes." I once missed a train in England by a few minutes, and when I expressed dismay that the next train was four hours off was told, perfectly reasonably, "You should have been here ten minutes ago, shouldn't you?"

Trent said,

September 8, 2008 @ 5:36 pm

John asked, "By 'bend your ear' you mean with your fingers?"

Hmmm, maybe I did use the idiom "bend your ear" in a unexpected way, but curiously enough, when I look down and cock an ear toward a speaker, I often do place a couple of fingers behind that ear.

So I suppose the answer to your question is yes.

Bryn LaFollette said,

September 8, 2008 @ 5:41 pm

Although many commenters are referring to a "recent rise" in uptalking, I wonder just how "recent" this speech behavior is in the US. I was born and raised in California, and have lived in California state (in various locations) for most of my life, just as my parents and grandparents have. I'm in my mid-thirties and would say that this is certainly a feature of most people of my generation from urban and suburban California. I don't know at what age one's usage no longer qualifies as "youth dialect" or the like, but my impression as been that this was also a feature of (at least some) members of my parent's generation as well, although not that of my grandparents. As far as the association with "Valley Girl" speech, more-so this has been a strong feature of San Franciscan usage since long before the rise of the term "Valley Girl". While I don't mean to say that this was widespread throughout the population of California for the last 50+ years, it should be noted that it's not new here, but is certainly a feature ripe for priming recency illusion.

Stuart said,

September 8, 2008 @ 7:13 pm

"Uptalk demands assent. It does not admit the possibility that the listener might disagree or have a different point of view. "

This only holds true where it is not the norm, of course. In NZ and Australia, it is so universal that it does not "demand assent" and is neither "smug" nor "bullying." I wonder if any US immigrants to countries whose English is predominantly "uptalking" have written about the adjustment and its psychological impact.

Paul Blankenau said,

September 9, 2008 @ 1:11 pm

To my ear, Taylor Mali says "un" a note lower than a fairly level "it has somehow become", followed by "cool" a note 2 or more steps higher than "un", higher than the earlier baseline. Also, the final rise is not completed until somewhere in the middle of the "oo" sound. Bush's notes are more separate; the final syllable or two are higher, but evenly so. Bush plays the piano. Mali plays the trombone, and slides during a syllable.

Bob Ladd said,

September 9, 2008 @ 4:40 pm

@Mark Liberman: Bob, are you confident that you could tell the difference, on short phrases whose F0 and amplitude contour was used to modulate a non-speech oscillator, in the mode of the example e.g. here?

If you make some examples, we can do the experiment, but the short answer is that I think I could as long as there is a "tail", i.e. unstressed syllables after the nucleus (last main stress) – in the sound example I posted, there are two postnuclear syllables, -mond and mine. The main phonetic difference between classic North American / Antipodean uptalk and the "Urban North British" statement rises is that the latter rise at the nuclear syllable and then level out or trail off, whereas in uptalk the pitch just keeps on rising.

[(myl) Response here.]

Ann said,

September 11, 2008 @ 5:06 pm

I find constant uptalk irritating also, which I suppose just indicates that I'm a member of a specific demographic group, Americans over 40 years old.

In a related issue, I moved away from my midwestern family home when I was in my early 20s, and now when I see my family again, listening to their conversation is the classic "nails on a chalkboard."

They all "punch" the words they want to emphasize with both rising pitch and volume, like this:

"I went to the MALL, and there was an ELEPHANT in the PARKING lot, and it was HUGE. But the weather was so HOT, and you could SEE that this poor ANIMAL was SUFFERING!"

While I listen to them, I imagine hooking up a machine to indicate the roller-coaster pitch of their conversation.

understanding-celtic-patterns-and-designs said,

November 20, 2008 @ 2:16 am

The so-called rise in uptalking may be criticized on many different levels, but from a linguistic analysis it offers compelling research in areas of sociology and cultural anthropology. Personally, I find it fascinating how such linguistic anomalies are not unusual at all; they are birthed within provincial microcosms and spread virally and organically. At least, that's my 2-cents on the subject.

garbanzo said,

November 25, 2008 @ 1:05 pm

@Arnold Zwicky: almost everyone reading the parent's letter seems to have taken the expression of extreme anxiety as feminine. Nice example of stereotyping. I suppose that if the letter-writer had expressed outrage and anger, people would have guessed that the writer was a man.

Very few comments have indicated one way or another what the assumption was. In my experience on internet forums, whatever gender is first mentioned in the comments becomes the default used by other posters.

It literally never crossed my mind that the concerned parent in the story might be a mother, until I ran into one of the comments that made that assumption. I took the parent's anxiety as stemming from concern that the uptalking could hinder the daughter's professional advancement. The daughter is described as having a Ph.D. and being a psychologist. The parent mentions that the daughter's friends include attorneys and physicians. To me this focus on professional status feels thoroughly paternal.

I speculate that each reader makes an assumption about the parent's sex based on whether the parent more closely resembles their own father or mother. In my case, I am also an adult daughter with a Ph.D. living in a distant city from my parents, and it is my father who is more concerned about my professional advancement (although he's never expressed anxiety about how I speak).

If you think uptalking is modern, feminine, teenage, or insecure, you’re wrong, k? - 22 Words said,

January 21, 2010 @ 6:50 pm

[…] read a little before you mock uptalking or pretend to understand […]

Young Women Often Trendsetters in Vocal Patterns - World Bad News : World Bad News said,

February 27, 2012 @ 4:37 pm

[…] an American boss has been famous to uptalk. “George W. Bush used to do it from time to time,” said Dr. Liberman, “and nobody ever said, ‘Oh, that G.W.B. is so insecure, only like a immature […]

Young Women Often Trendsetters in Vocal Patterns | All Health News said,

February 28, 2012 @ 8:01 am

[…] an American boss has been famous to uptalk. “George W. Bush used to do it from time to time,” said Dr. Liberman, “and nobody ever said, ‘Oh, that G.W.B. is so insecure, only like a immature […]

Young Women Change Our Language | Media Editing said,

February 28, 2012 @ 6:02 pm

[…] American president has been known to uptalk. “George W. Bush used to do it from time to time,” said Dr. Liberman, “and nobody ever said, ‘Oh, that Bush is so insecure, just like a young girl.’ ” The […]

Arana: Good sociolinguistic conclusion despite questionable examples said,

January 16, 2013 @ 10:30 pm

[…] am less familiar with the literature on up-talk, but can point to the ever-insightful Language Log for meta-analysis of work on the phenomenon. Mark Liberman reviews work in which the rising […]

Linguistics + New Media = The Convergence of Oral and Written Cultures | Technology: Innovation or Oblivion? said,

February 21, 2013 @ 6:44 pm

[…] president has been known to uptalk. “George W. Bush used to do it from time to time,” said Dr. Liberman, “and nobody ever said, ‘Oh, that G.W.B. is so insecure, just like a young […]