A new Sinograph

« previous post | next post »

On being ugly and poor, with an added note on consumerism.

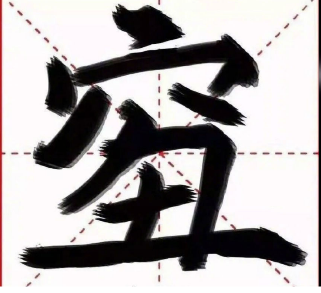

Every so often, for one reason or another, somebody creates a completely new Chinese character. Here's the latest:

"'I’m So Qiou' — The New Chinese ‘Character of the Year’ is ‘Dirt-Poor & Ugly’

If there is one single word for being ‘dirt-poor’ and ‘ugly’ it would be ‘qiou’ — a character many self-mocking young Chinese say they identify with."

By Crystal Fan, Manya Koetse, and Miranda Barnes, What's on Weibo (12/5/18)

This new bit of Internet slang is a hybrid character combination of qióng 穷 and chǒu 丑, "poor" and "ugly". It's interesting that the Romanization that seems to have been adopted for the character is "qiou" (no indication of tone).

David Moser asks:

My puzzlement is: How is this Pinyin blend "qiou" pronounced any differently than "qiu"? The few Chinese I've mentioned this to have never seen the character online, but in any case, when I ask them if "qiu" vs. "qiou" triggers any subtle pronunciation distinction, they sound the two out a few times, shrug, and say they're both just "qiu". Which makes me think whoever came up with this Romanization was going for what is primarily a visual blend, tacking the "ou" of "chou" onto the the "qi" of "qiong". Not a matter of phonetic rendering, but just optics.

I'm going to dig a little bit deeper into this and see if something else is happening.

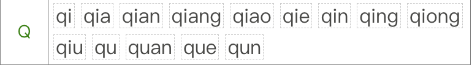

First of all, according to the phonology of Modern Standard Mandarin (MSM), there are certain phonological constraints that are operative. Here are the only permissible syllables beginning with "q":

So "qiou" is an illegal syllable. It doesn't exist in the phonological system of MSM. Yet netizens are using "qiou" to represent the sound of this newly invented character.

"Qiou" is obviously a kind of fǎnqiè 反切 ("cut-and-splice; countertomy") spelling where one takes the first part (the initial) of one character and the second part (the final) of another character to represent the pronunciation of a third character. In this case, we have the "qi-" of qióng 穷 ("poor") and the "-ou" of chǒu 丑 ("ugly"), which yields "qiou".

The problem is that "qiou" is an illegal syllable within the phonology of MSM. So how should it be pronounced?

I asked several of my graduate students from mainland China, and got a variety of answers.

1. I guess qiu and qiou are basically the same in pronunciation. But I might still need a few seconds to comprehend qiou in a conversation, for it seems so contextual.

2. The pronunciation of "qiou" is different from "qiu", since in "qiou" you have to pronounce the "-ou" part, which is different from just "-u". Thus, I would say "qiou" is much like "qi+ou", and you have to emphasize the ou, otherwise, it is gonna be just like "qiu". I think this irregular pronunciation "qiou" is distinctive enough that it could be understood in a certain context.

3. Qiou and qiu are the same, and qiou in fact should be standardly written as qiu. My high school Chinese teacher told me that iou is shortened as iu.

We'd be in even more of a phonological quagmire if the inventor of the character had arranged the two parts as chǒu 丑 ("ugly") and qióng 穷 ("poor"), which would yield "chiong", an even less likely configuration than "qiou". In this case, however, we'd run up against an orthographic prohibition, since the ⽳ component (radical; semantophore; [semantic] classifier; key; etc.) can only occur at the top of a character, not in any other position. However, if we really want to be playfully perverse, we could just jolly well put 丑 on top and ⽳ on the bottom, which would give "chiong", however that might be pronounced, and signify "ugly and poor", as opposed to "poor and ugly" for "qiou". But I doubt that even the most scriptally sacrilegious netizen would be that iconoclastic and irreverent toward the Chinese writing system.

Addendum

Pondering the viral popularity of this new character for "poor and ugly", one of my graduate students from China who is neither poor, ugly, nor vain, was prompted to make the following observations on the changing state of the mindset of young Chinese today:

I have discovered that Chinese youth are more daring to unabashedly recognize their predicament and inability, which would be so humiliating for the older generation to admit. Young people today are in fact earning much more than their parents used to, but their lavish habits of consumption push them to the abyss of poverty. I recently have been experimenting with stopping shopping for clothes and I successfully prevented myself from buying any outfit for more than three months! The most striking fact is that I have no shortage of outfits even though I didn't buy any over the past three months.

We young people should really reflect upon our consuming habits and learn from our parents of their economy and getting rid of vanity!

Readings

- "Duang " (3/1/15)

- "More on 'duang'" (3/19/15)

- "Jackie Chan Campus Station" (4/10/15)

- "Reanalysis, Jackie Chan edition" (9/6/18))

- "How to generate fake Chinese characters automatically" (12/30/15)

- "Is it necessary to invent a new Chinese character for 'ivory'?" (1/2/16)

- "Ted Chiang uninvents Chinese characters" (5/13/16)

- "How many more Chinese characters are needed?" (10/25/16)

- "New radicals in an old writing system" (8/29/12)

- "The unpredictability of Chinese character formation and pronunciation" (2/6/12) — for Xu Bing's famous Tiānshū 天书 (A Book from the Sky)

[Thanks to Zeyao Wu and Qing Liao]

Chris Button said,

December 5, 2018 @ 2:11 pm

I would agree. In bopomofo, "chou" is ㄔㄡ and "qiu" is ㄑㄧㄡ (i.e "qiou")

DaveK said,

December 5, 2018 @ 2:17 pm

“Ugly, poor and misspelled is no way to go through life”

Neil Kubler said,

December 5, 2018 @ 5:25 pm

According to the phonetics of Modern Standard Mandarin, "qiou" is not incorrect, as the spoken syllable includes a "q-" initial and a "-iou" final (composed of the glide -i- and the diphthong "ou"). However, according to the rules of the Pinyin romanization system, "qiou" is indeed an "illegal" syllable. The reason for that lies in the fact that when Pinyin was created, it was originally designed to replace Chinese characters as the future writing system of China, hence was designed to be as simple as possible. Since there is in Chinese no contrast between "qiou" and "qiu", might as well WRITE (but not pronounce) the syllable with one vowel less as "qiu". (This solution makes great sense for native users, even though for foreign learners it would have been better to leave it as "qiou".)

Jacob said,

December 5, 2018 @ 6:32 pm

I wholeheartedly agree with your student's assessment about younger generations being more comfortable with self depracating humor. To wit: the top trending comment I saw on Weibo was:

#2018年度汉字qiou# 网友:这个字……是不是念“wǒ”??[跪了]

This character…is it pronounced wǒ? where wǒ = 我 or I/me.

Antonio L. Banderas said,

December 5, 2018 @ 6:37 pm

is an attempt at representating a syllable contraction by means of pinyin

In The Sounds of Chinese, Yen-Hwei Lin, page 181 uses IPA,

LINK: https://i.imgur.com/A65DfTa.jpg

[img]https://i.imgur.com/A65DfTa.jpg[/img]

John Rohsenow said,

December 5, 2018 @ 7:06 pm

"My high school Chinese teacher told me that -iou is shortened as -iu."

"How is this Pinyin blend "qiou" pronounced any differently than "qiu"? "

I find it interesting that no one addressed the question of the tone of

'qiou'. In what tone is it pronounced? (Is it in fact ever pronounced aloud?)

Leaving the rules of HYPY spelling aside, it seems to me that the amount

of "o" in "-iou" varies with the length of the syllable depending on the

tone: less in the shorter high tone, & more audible in the more elongated low, 'dipping' tone. — I guess if it's just a visual "play on characters', it doesn't matter.

btw: how do people enter this 'character' using an ordinary computer keyboard, or using the kind that 'recognizes' characters written on a screen?

Michael Watts said,

December 5, 2018 @ 7:45 pm

You can't; in order to enter a character and have it display, you'd need a font that defines the character. (If you're not worried about display, you can enter it any way you want, and just tell people what you meant.)

You're free to describe it though. For example, someone identified 覅 in speech to me as "勿要在一起的那个字" ("that character with 勿 and 要 together"). This is moderately interesting in itself, as the 勿 is on the right and the 要 is on the left.

Michael Watts said,

December 5, 2018 @ 7:51 pm

Heh. I'm guessing this student is female.

I don't think I've ever bought an "outfit", and I, like many people I know, will go years at a time without buying clothing.

Victor Mair said,

December 6, 2018 @ 12:29 am

覅

Without looking it up, do you know how to pronounce it?

unekdoud said,

December 6, 2018 @ 12:54 am

Aside from standard Pinyin orthography, is there evidence for/against a distinction between the supposed qiou and qiu in speech? Would pronouncing 九 with an -ou vowel be considered an error?

@John Rohsenow: I don't think it's just tone, as I don't read 由邮游犹尤 with identical vowel sounds.

Victor Mair said,

December 6, 2018 @ 1:16 am

The second informant cited in the o.p. states that she would pronounce "qiou" differently from "qiu", and she describes the difference.

Moa said,

December 6, 2018 @ 8:28 am

I'm curious how to pronounce the qiu without the ou part. I was taught that the qiu in Mandarin Chinese is pronounced with the ou sound, similar to what the third respondent writes. Do you just leave it out so it sound more like "qi" or do you use another sound? Or is the difference not in the sound, but rather in the intonation or the stress? Could anyone please explain?

Philip Taylor said,

December 6, 2018 @ 9:11 am

To me (and please forgive the very broad (and poor) transcription of the initials in what follows), I would expect qiu to be something like /tʃju/ whilst qiou to be more like/tʃjoʊ/.

Jarek Weckwerth said,

December 6, 2018 @ 10:49 am

So is the syllable an accidental gap in the inventory, or is there a general constraint against /-ou/?

Chris Button said,

December 6, 2018 @ 11:11 am

My guess (not having heard her but judging by her description and Mandarin phonotactics) is that she was probably breaking it into two syllables.

This reduction of "you" to "-iu" when preceded by another onset – compare "you" and "qiu" in bopomofo as ㄧㄡ (i.e. "iou") and ㄑㄧㄡ (i.e. "qiou" – also pertains to "wei" and "-ui". So for example in bopomofo "wei" is ㄨㄟ (i.e. "uei") and "shui" is ㄕㄨㄟ (i.e. "shuei").

It might be noted that the "ou" in "chou" (ㄔㄡ) and the "u" in "qiu" (ㄑㄧㄡ) are naturally going to sound slightly different phonetically due to the differences elsewhere in the syllables, but phonemically they should be treated identically. One of the many reasons I've always favored bopomofo over pinyin…

~flow said,

December 6, 2018 @ 11:29 am

I think the assertion that 穴 can only appear on the top of a character and not in any other position is only 99% correct:

U+8313 茓 xué 做囤用的狭而长的席称“茓子”。通常是用秫秸或芦苇的篾儿编成的。亦作“踅子”。用茓子围起来囤粮食。

U+66cc 曌 zhào 同“照”,中国唐代武则天为自己名字造的字。

U+2593e 𥤾 《康熙字典》 《字學指南》苦弔切。同竅。或作䆻。

茓 is, formation-wise, a run-of-the-mill phono-semantic character, where 穴 indicates the pronunciation. One could argue that it is, formation-wise, not so much 穴 put under 艹, but rather, it is 穴 with a 'diacritic annotation' 艹 put on top of it. I don't know how common it is, but one could point out that it is within the Unicode CJK Unified Ideographs Block, it shouldn't be exceedingly rare.

曌 is a rare character, but also a famous one, since it was created by Empress Wu Ze Tian to write her own name; it does appear in the 新華字典. So maybe at some point in the future, we will see Unicode and dictionaries contain qiou—making up a character and getting dictionaries to list it is certainly a possibility! More to the point, there are a few not so very rare characters like this one (e.g. 櫋) where 穴 does appear in a middle position, but, indeed, there are, as far as I could find out, only about 100 characters out of ca. 75000 where 穴 is below any other element, a majority not within the CJK Unified Ideographs Block.

Among these is 𥤾, which indeed has a 'full' or 'strong' component (as opposed to a 'diacritical' one like 艹) on top and 穴 at the bottom. One can somewhat tell from the fact that Kangxi gives it only a minimal treatment that it is probably indeed obscure. It is an interesting character in itself since it is formed by writing out its own definition, as it were: it has 孔 'empty' at the top and 穴 'hollow' at the bottom, and it means 孔穴 (~空穴) 'hollow part, orifice'.

Victor Mair said,

December 6, 2018 @ 1:10 pm

Referring to my previous comment, 覅 is pronounced fiào in Mandarin, which is illegal both in Hanyu Pinyin and in MSM phonology. It is common in Wu and related topolects, where it has the following pronunciations:

fiau(绍兴话、苏州话、无锡话、常州话、衢州话、上饶话)、viau(上海话、南通话)、and fai(温州话)

In terms of its construction / composition, 覅 is a compound character, consisting of wù 勿 ("don't") and yào 要 ("want") positionally in reverse order, which — following the method of fǎnqiè 反切 ("cut-and-splice; countertomy") spelling described in the o.p. and the model of béng 甭 ["no need to; don't"], which derives from bù 不 ["no; not"] + yòng 用 ["use"] — would result in Mandarin "wào", which is nonexistent, impermissible in MSM phonology. So fiào 覅 resembles the qiu / qiou character discussed in the o.p., both in its "illegal" phonology and its irregular orthography. What's particularly interesting to me is that 覅 has a topolectal inspiration, whereas the ⽳+丑 character was invented by an individual, evidently within a Mandarin speaking environment (at least this new character is being interpreted as having a basis in Mandarin pronunciation.

Victor Mair said,

December 6, 2018 @ 1:20 pm

I knew before making the statement that 穴 can only appear at the top of a character that ~flow or someone like ~flow would find a miniscule number of exceedingly rare exceptions. I just wanted to smoke them out.

Chris Button said,

December 6, 2018 @ 1:45 pm

Thinking about this again, I suppose she could be saying "qi-" and then intentionally forcing the articulation of "-ou" as if it had been said with "ch-" before rather than "qi-" to give the effect of something different, but that is hardly natural. I would also venture to suggest that she is not a Taiwanese speaker of Mandarin since it is only a "problem" (and an artificial one at that) as a result of the use of pinyin.

Matt Anderson said,

December 6, 2018 @ 2:06 pm

Wow, fiào! That's a great pronunciation.

Upon glancing at 覅, before seeing its official pronunciation, I immediately read it out as biáo, and I wasn't sure why at first—but I must have been associating it with biáo 嫑, another topolectal character with the same meaning.

Strangely, while biao isn't an "illegal" syllable in MSM, 嫑 is the only character I can find pronounced biáo. At least that's how I've always heard it was pronounced, and that's what's given on sites like mdbg.net and zdic.net.

I looked for it (and any other words pronounced biáo) in three of the largest Chinese dictionaries. I couldn't find it at all in Zhonghua zihai (self-proclaimed to be the Chinese dictionary containing the most characters) or Hanyu da cidian, but it is in Hanyu da zidian, where it is given the pronunciation báo (and it turns out that wiktionary and the unicode both give it this reading as well). None of these works contain any characters with the reading biáo, as far as I can find.

So is 嫑 really pronounced báo (as given in the more official/prestigious sources), or is it really pronounced biáo, but sources like Hanyu da zidian and unicode convert this to báo either mistakenly (this could all originate from Hanyu da zidian itself), or because biáo was thought to be "illegal"? I have no idea. Or does it have no proper pronunciation in MSM at all, but only in one or more other topolects? I only know that I've encountered the character several times and, until today, only seen it given the pronunciation biáo.

~flow said,

December 6, 2018 @ 3:35 pm

@VHM which is why I hesitated to comment at all.

Jerry Packard said,

December 6, 2018 @ 10:30 pm

The tone would have to be third, because tone follows the second fanqie syllable.

The other Eric said,

December 8, 2018 @ 12:53 am

People have illustrated this character merely by drawing it; see the image that accompanies this post.

But the Wikipedia article for Changjie states that early devices did not use Big5 or Unicode to encode input, but instead had a dedicated character generator, which merely recorded keystrokes as ASCII, and then displayed the corresponding Chinese text according to Changjie's rules of decomposition, allowing one to input unattested characters. Ever since duāng I have wondered about the exact key sequence required to produce that character (i.e. 成 on top of 龍).