Bad words on WeChat: go directly to jail

« previous post | next post »

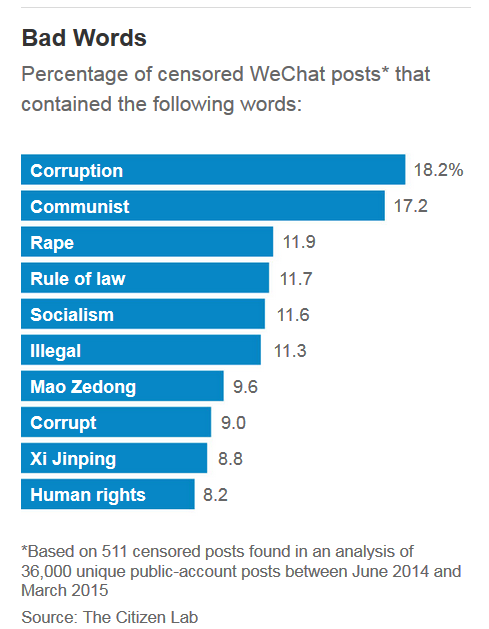

With over 980 million monthly active users, WeChat is an extremely popular messaging app in China. However, in the Orwellian climate of the PRC, you had better watch your language carefully, lest you get whisked off to jail without trial. Here are some words that can result in your incarceration:

This chart comes from Eva Dou's copiously documented article, "Jailed for a Text: China’s Censors Are Spying on Mobile Chat Groups", in WSJ (12/8/17).

What's wrong with these words? If used in the right way, most of them could be highly praiseworthy in a communist society, even one with Chinese characteristics. What could be more glorious than to laud Mao Zedong, Xi Jinping, communism, socialism, human rights, rule of law, and — above all — the supposed fight against corruption? The problem is when you use them in the wrong way, which becomes a grave offense against the state.

This means that the PRC censorship apparatus first flags sensitive words (that's the easy part), then it has to determine the context in which these words are being used. The amount of human, financial, and electronic resources devoted to such searches is mind-boggling, and yet the Chinese government — for reasons that are beyond my ability to comprehend — feels compelled to expend them.

As a result of this extreme paranoia about what citizens are thinking and saying, a large part of daily vocabulary becomes suspect. I encourage those who are interested in this phenomenon to read "Banned in Beijing" (6/4/14), written on the anniversary of the Tiananmen Massacre, which shows the ludicrous lengths to which PRC censors will go to ensure the purity of the thoughts, words, and deeds of Chinese citizens.

Sometimes, the censors begin to look pretty ridiculous, as when they outlawed the word "jasmine" in 2011, particularly since it refers not just to the Jasmine Revolution, but also to a favorite flower, tea, and folk song.

mòlì 茉莉 ("jasmine")

mòlì chá 茉莉茶 ("jasmine tea") OR mòlìhuā chá 茉莉花茶 ("jasmine tea") OR xiāngpiàn 香片 ("scented [usually with jasmine] tea")

mòlìhuā 茉莉花 ("jasmine flower", name of a popular folk song; presidents Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao were both excessively fond of this song, and there are videos of them singing it, so it becomes especially awkward to try to forbid citizens to use the word mòlì 茉莉 ("jasmine")

Today, of all days in the year, however, the CCP censors are out in fuller force than usual, with the result that a goodly portion of written Chinese has been eviscerated.

[VHM: That was followed by a list of scores of expressions that were disappeared from internet vocabulary during the commemoration of the 25th anniversary of the Tiananmen Massacre.]

This reminds me of an experience I had in Beijing during the mid-80s — before the internet age — which demonstrates how an atmosphere of repressive censorship can condition the way people talk, even in private.

I was walking around Wèimíng hú 未名湖 ("Unnamed Lake") on the most secluded part of the Peking University campus with Yin Binyong, the applied linguist. Nobody else was around. In the course of my conversation, I mentioned the words gémìng 革命 ("revolution") and gǎigé 改革 ("reform"). As I did so, Yin recoiled as though he had received an electric shock. I asked him what was wrong, and he said, "Shhh! We don't use these words anymore, because…" (see the last paragraph below for the reason). Whereupon we quickly changed the subject.

When I first went to China in 1981, I had two objectives. The first was to examine Dunhuang manuscripts in the National Library. Mission accomplished! The second was to liaise with colleagues at the Wénzì gǎigé wěiyuánhuì 文字改革委员会 (Script Reform Committee). From my meetings on that occasion, I became close friends with Zhou Youguang, Yin Binyong, and other outstanding Chinese language reformers. Ironically, though, not long thereafter, the Wénzì gǎigé wěiyuánhuì 文字改革委员会 (Script Reform Committee) had to change its name to Yǔyán wénzì gōngzuò wěiyuánhuì 国家语言文字工作委员会 (State Language Commission), as described in this comment and in "Critical thinking" (3/31/14). It was no longer possible for a government agency to refer to itself as being engaged in "reform".

As Yin Binyong explained it to me that day next to the Unnamed Lake, gé 革 means "dismiss; remove" and implies that mìng 命 ("the mandate [of heaven]", i.e., the right to rule) could be "taken away" by the people. Consequenty, once ensconced in power through gémìng 革命 ("revolution" — removing the mandate to rule of the KMT), the CCP had effectively outlawed future 革ing.

[h.t. June Teufel Dreyer]

ErikF said,

December 17, 2017 @ 2:43 pm

@Victor Mair: In your examination of older (pre-Communist) texts, were there similar attempts to control language? My guess is that it would have been easier as fewer people were in a position to write anything in the first place.

I remember reading about the fairly severe restrictions that England placed on printing at first: Did governments become more worried about censoring after mass publication became possible? It's something that I briefly touched on in some library science classes, but it was never a focus at the time. I was wondering if anyone may have done more research (and if you have references, I would love to read them!)

Dan T. said,

December 17, 2017 @ 4:13 pm

Crimethink!

Michael Watts said,

December 17, 2017 @ 11:34 pm

With Xi Jinping and Mao Zedong on the list, it reminds me of the imperial name taboo.

Victor Mair said,

December 18, 2017 @ 9:27 pm

@ErikF:

Yesterday, shortly after you posted your comment, I was going to answer with the information below, but I was diverted by other tasks. Fortunately, Michael Watts mentioned taboo, which is the first thing I thought of in preparing to reply to you.

For Chinese taboo language, see the references here. Those that compare English and Chinese taboo language should be of particular interest to you.

See also "China's Censored World – The New York Times".

Other facts that should be taken into account are the vast gulf between the Literary / Classical and Vernacular / Oral realms in traditional culture. It was very much frowned upon for elite, literate individuals to use vulgar, popular language. Given that literacy levels were extremely low until recent times, even though the government didn't have electronic means of censorship, there were other ways for language to be policed, as you suspected.